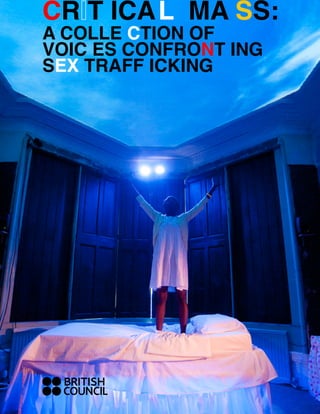

Critical Mass: A Collection of Voices Confronting Sex Trafficking

- 1. CR T ICAL MA SS: A Colle ction of Voic es Confront ing Sex Traff icking

- 2. About the British Council The British Council creates international opportunities for the people of the UK and other countries and builds trust between them worldwide. We are a Royal Charter charity, established as the UK’s international organisation for educational opportunities and cultural relations. Our 7,000 staff in over 100 countries work with thousands of professionals and policy makers and millions of young people every year through English, arts, education and society programmes. We re-energize the transatlantic relationship and partner with US-based organisations to work on shared agendas worldwide. A quarter of our funding comes from a UK government grant, and we earn the rest from services which customers pay for, education and development contracts we bid for, and from partnerships. For more information, please visit: www.britishcouncil.org/usa. You can also keep in touch with the British Council on Twitter @usabritish and www.facebook.com/britishcouncilusa. About Roadkill In 2010 award-winning actor and theater director Cora Bissett’s critically acclaimed work Roadkill, which exposes the hidden world of sex trafficking, was the first production in Edinburgh Fringe history to win every major theater award. As part of the British Council Showcase in 2011, Roadkill again captured the hearts and minds of audiences from around the world. In 2013 Roadkill has its US premiere In Chicago and New York presented by Chicago Shakespeare Theater and St. Ann’s Warehouse, two of America’s leading producers, presenters and commissioners of innovative global theatrical events. Roadkill, produced by Pachamama Productions and Richard Jordan Productions in association with Traverse Theatre, is based on a real-life encounter with a young woman from Benin City, Nigeria, who has been trafficked to Scotland. Staged in a seemingly average apartment, the site-specific nature of the work places the audience in the young woman’s world to witness at close quarters how her hopes of a new life are turned into violent scenes of rape, brutality and captivity in the sleazy world of sex trafficking. Together with strong writing and excellent performances from the cast, this groundbreaking production is a deeply affecting work which takes even the most seasoned theater goers on an insightful journey beyond their comfort zones. CREATIVE TEAM | Directed by Cora Bissett | Text by Stef Smith | Assistant Director/Sound Artist, Harry Wilson | Designed by Jess Brettle | Digital Media Artist, Kim Beveridge | Animation Artist, Marta Mackova | Lighting Design by Paul Sorley | CAST | Mercy Ojelade, Adura Onashile, John Kazek Pictured above: Mercy Ojelade | All photos by Tim Morozzo ABOUT THIS PUBLICATION The British Council highlights the best of UK culture in a spirit of cultural exchange, so we are delighted to organize and support a public program to engage wider and diverse audiences to examine the issues of human and sex trafficking. Viewing these problems through a cultural relations lens underscores the complex causes at their roots, such as globalization and cultural beliefs, and the collective solutions they require, such as education and capacity building from all the societies involved. The arts are an ideal vehicle for dialogue, and this publication of essays, poetry, interviews and portraits commissioned from or submitted by leading advocates, academics, artists and survivors helps to contextualize the performance and broaden audiences’ understanding of and public engagement with the issues of human and sex trafficking dramatized in Roadkill. Join the conversation as it unfolds on the Roadkill Forum: http://usa.britishcouncil.org/art/roadkill. Follow us on Twitter (@usaBritish and #Roadkill13) and Tumblr (#Roadkill13)

- 3. Contents 2 Introduction: Paul Smith and Cora Bissett 5 Foreword: Baroness Goudie 6 A Critical Review of Roadkill: Lyn Gardner, The Guardian 8 5 Things to Know About Human Trafficking: Amanda Kloer, Change.Org with CNN Freedom Project 10 Stolen Voices: Bidisha 16 Restoring Confidence, Envisioning the Future: British Council in collaboration with Restore NYC 20 Interview: Siddharth Kara, Harvard Kennedy School 22 CAASE: Ending Harm, Demanding Change in Chicago and Beyond: Rachel Durchslag 24 Five Ways to Stop Human Trafficking and Sexual Exploitation: Rachel Durchslag 25 A Path to Service: Jessica Minhas, The Blind Project 28 Measure Your Slavery Footprint 30 Spotlight: Winner of the Challenge Slavery Tech Contest 32 Fus Ro Dah: Sarita, Sex Trafficking Survivor Conten ts

- 4. 2 INTRODUCTION Paul Smith is the British Council Director USA The British Council, around the world and here in the United States, engages strongly with civil society and community leaders, with decision makers and opinion formers and, above all, with young people to encourage them in social enterprise and in contributing to resolving issues of global importance. One way in which we do this is by championing powerful arts productions from the UK that depict and explore the ravages of human crisis and critical aspects of cultural identity. Roadkill is a site-specific production that deeply immerses its audiences in the tragic narrative it unfolds. As such, Roadkill’s innovative form and compelling content make this appropriately the latest in our series of dramatic British productions which have recently toured the USA. These have included powerful and challenging productions exploring the complex repercussions of conflict in Iraq and Afghanistan, such as Black Watch from Edinburgh and The Great Game: Afghanistan from London, which were well-received by American audiences. Art has the power to transform perceptions, assumptions and attitudes and to build the will for responsible action. Roadkill causes its audiences to experience the horrors endured by millions of people—particularly women and children—who are trafficked for the purpose of sexual exploitation. It breaks the heart and compels determination for action. The 17th - century writer and historian Thomas Fuller wrote “If it were not for hopes, the heart would break;” Roadkill is a story that hangs on hope. The British Council is on the ground in over 100 countries, many of which are affected by the pressing issue of human trafficking. This anthology, which reveals perspectives from survivors and advocates, helps tell the stories of real characters who, every day, experience this terrible reality. It is our hope that this US tour of Roadkill, and the public events that accompany it, will create a legacy of understanding, concern and commitment. Pictured Mercy Ojelade and Adura Onashile INTR ODUC TI ON PAUL SM ITH

- 5. 3 Cora Bissett is an Actor, a Director, and is the Artistic Director of Pachamama Productions Photo by Stephanie Gibson Roadkill began as an idea way back in 2009 when I came into contact with a young woman who had been trafficked from Africa to Scotland for the purposes of sexual exploitation, by an older woman. She stayed with me for a short while. Trafficking was an issue I knew a fair bit about, having kept abreast of a series of articles which had appeared in The Scottish press in recent years. But when a young woman quite literally lands on your doorstep, and wakens you with her screams in the night, Trafficking ceases to be an ‘issue’ and becomes about an individual, and in this case for me, a friend, someone sharing my home. I wanted to let people know what was going on right now in our city. I wanted somehow to give people the experience I had had of coming into such alarmingly close contact with this world which exists quite literally on our doorstep, and that is how I settled upon the idea of putting the play into a flat and transporting the audience there. The writer Stef Smith and I researched many similar stories and case studies and even travelled to Italy where many Nigerian women are trafficked, and we interviewed people who had escaped traffickers. From this array of stories, we created our script. And so ‘Roadkill’ became an amalgamation of many women’s stories but sparked by that very first meeting with one. By taking the audience to a location they did not know, and keeping them in a small flat, they too were disorientated and trapped in a space, in the girl’s world for the duration of the piece. We shared the journey with her, rather than watch it comfortably from afar. We were in her world, and the impact of that was unprecedented. Roadkill made newspaper headlines, and trafficking was being discussed on TV shows, arts shows, and mainstream radio programmes. The profile it was raising was unprecedented. People could not believe this was happening in Scotland, right here, right now. We gave the audience sheets at the end of each show with information on organisations they could contact should they like to donate, support, campaign, or take direct action. The Scottish Refugee Council was one of these places, and I was reliably informed that they had been inundated with calls and emails from audience members who wanted to help. Who wanted change. This was the power of being engaged in that story. Roadkill’s journey, like the journeys of countless thousands of girls around the globe is far from over. We have played in Paris, London, Glasgow, Edinburgh and now The U.S. Rather sadly, the story is as pertinent and current in every city around the world as it was when it first emerged that summer in Edinburgh. I hope that the spotlight it brought to bear in other countries, can serve to do the same here in the U.S. and that in partnership with all the organisations who are working so hard to eradicate this most awful of human rights abuses, we can focus on ways to inform, affect and activate our societies. COR A BI SSET T

- 7. 5 FOREWORD Baroness Goudie is a senior member of the British House of Lords and global advocate for the rights of women and children. She is on the board of Vital Voices, is involved in promoting gender equity with both the G8 and G20 and is also the Chair of the Women Leaders’ Council to Fight Human Trafficking at the United Nations. I became involved in human trafficking in the year 2000 when I attended a meeting at the United Nations with Ambassador Melanne Veveer and Winch Yu, who at the time were Director of Human Trafficking and Human Rights at Vital Voices. At this meeting, my eyes were opened to the extent of human trafficking, the damage that is done to human beings and the amount of money generated from these crimes. I then became a member of the Executive and Board of Vital Voices Global Partnership. Vital Voices is committed to fighting human trafficking around the world. The UN continues to battle human trafficking under their Department of UNODC, which covers serious crimes, drugs, and human trafficking. As a member of The House of Lords, I have lobbied the British government’s efforts on human trafficking. Both the Palermo Convention and the EU Directive on Trafficking have subsequently strengthened awareness and include cross border prosecutions. Human trafficking is the trade of human beings for the purpose of sexual slavery or forced labor. Currently there are 21 million people forced into labor around the world including forced sexual exploitation. Of that number, 5.5 million are children. Potential victims have been identified in over 90 countries. As the UK’s cultural relations organization, the British Council touches the lives of tens of millions of people around the world each year with its arts programming by supporting projects that facilitate public engagement with and dialogue around important international issues such as social change, cultural identity and conflict and in the case of Roadkill, human trafficking. The human trafficking issue affects every country. Vital Voices has an excellent toolkit available for download on the Internet, which will reach broader audiences globally. The timing is crucial as we are in an economic downturn, and it is easy for families to be persuaded to sell their children, for women to be conned into domestic servitude and sex parlors, and for men to be taken and forced into labor in construction and fishing industries. Sex trafficking is not just about young women and girls, but it is also about boys and young men. There are 5.5 million children exploited around the world. This is a huge human rights and healthcare issue. Those that are trafficked do not live long lives. It is critical for awareness to be raised at an inter-country level; at meetings such as the G8 and the G20. The United Kingdom and the United States are working diligently to have human rights issue on the agenda. Every individual must lobby their governments both locally and nationally to fight for the eradication of human trafficking, because it will not go away by itself. The amount of money being made is in the billions. Trafficking is the second biggest organized crime, the first being arms, followed by trafficking, then drugs. A human being can be used more than once. It is time to put an end to this crime. F OREW ORD

- 8. 6 A CRITICAL REVIEW OF ROADKILL Lyn Gardner has been going to the theatre regularly since early infancy. She studied Drama and English at Kent University. She was a founder member of the City Limits cooperative where she edited the theatre section, before joining the Guardian. Preface It’s almost three years since I first saw Roadkill, but if anything it is more vivid in my mind than when I first saw it. So it should be. There are nights when I walk home though my part of London and look at the shrouded windows of houses and flats and wonder if there is a Mary behind those curtained windows enduring appalling abuse. Sex trafficking is a growing international problem and one that most of us think has nothing to do with us. But no doubt many ordinary people said that about another kind of slavery in the 18th and 19th centuries. But it does have something to do with us, and one of the great strengths of Roadkill is that it reminds us that it does. It refuses to let us off the hook. Its very form—which places the audience in the role of voyeurs who sit passively and watch as terrible things unfold in front of us—reminds that we are all complicit in a system which sees human beings merely as a commodity to be bought and traded. More than that, Cora Bissett’s uncompromising production makes us look hard and not look away at something we might prefer not to know about or pretend doesn’t happen. If Roadkill was performed in a theatre, it would be too easy to dismiss as a piece of fiction. We would be shocked while watching but when we left the theatre we would leave it there as we headed back to our comfortable lives. But its intimacy, form and site-specific nature ensure that we cannot just leave it behind. It is of course a piece of fiction, but one that is based on a reality that many young women like Mary are enduring every day. But it is more than that: it is a call to arms, an invitation to act and campaign, and most of all a reminder that if we simply turn a blind eye and refuse to look at the problem full on, nothing will change and we are failing all the Marys, everywhere. A CRITI CAL RE VIEW 6

- 9. 7 The young black girl in the white dress sitting a few seats away from me on the bus laid on by the Traverse theatre is little more than a child. She is chattering excitedly about the sights she sees to her “auntie”, a flashily dressed young woman, and to anyone who will listen. She has never seen buildings like this in Nigeria. Her enthusiasm bubbles over. A few minutes later, in Cora Bissett’s off-site production, now in a dingy flat off Leith Walk, we see the same young woman again. Now her white dress is torn and bloody; she shakes. The lamb has been sacrificed on the altar of the profitable sex trade. In the space of just a few minutes, she has lost her virginity, her innocence, her passport, her past and her future. Over the next hour, we watch like ghostly voyeurs as Mary’s life turns into hell on earth, and she is manipulated by Martha, the auntie she thought would protect her. It’s a familiar tale, and one that is being told elsewhere on the Fringe. But in this uncompromising production, it’s up close and personal. It doesn’t feel as if this is just a play. Just as Mary cannot escape from the shuttered basement room where men inflict appalling violence on her body and then review her performance on the internet as if they’re assessing a hotel or Roadkill Lyn Gardner, The Guardian, Thursday 12, August 2010 (reprinted with permission) This is a critical review of the production Roadkill from 2010, the year the show won Amnesty International’s “Freedom of Expression” Award at the Edinburgh Fringe Festival. meal, so Bissett ensures that we cannot escape the appalling truth of Mary’s life, and all the trafficked young women like her. The only way to escape is to shut your eyes, to pretend it isn’t happening. None of us in the room can quite meet each other’s eye. This is by no means a perfect production, but it is an almightily powerful one. There is some cunning use of video to conjure both real demons and those of the mind, and a soundscape that offers distant children’s voices, and a snatch of Strange Fruit. There are remarkable performances, too, from Mercy Ojelade as a Mary you want to cradle in your arms, Adura Onashile as the damaged and manipulative Martha, and John Kazek as a series of men who abuse or fail Mary. Taking the show out of the theatre is more than a mere gimmick, though it does also raise uncomfortable questions about theatre’s and the audience’s responsibilities. Are we simply staring at the animals in the zoo, or will we actually act after seeing the show; file it away under “interesting experience” or do something? The power of the piece is that you cannot forget the laughing girl in the white dress; nor should you. She’s out there somewhere running for her life.

- 10. 8 5 THINGS TO KNOW ABOUT HUMAN TRAFFICKING Special to CNN (reprinted with permission) Amanda Kloer is an editor with Change.org, where she organizes and promotes campaigns to end human trafficking. She has created numerous reports, documentaries and training materials on human trafficking in the United States and around the world. Human trafficking might not be something we think about on a daily basis, but this crime affects the communities where we live, the products which we buy and the people who we care about. Want to learn more? Here are the five most important things to know about human trafficking: 1. Human trafficking is slavery. Human trafficking is modern-day slavery. It involves one person controlling another and exploiting him or her for work. Like historical slavery, human trafficking is a business that generates billions of dollars a year. But unlike historical slavery, human trafficking is not legal anywhere in the world. Instead of being held by law, victims are trapped physically, psychologically, financially or emotionally by their traffickers. 2. It’s happening where you live. Stories about human trafficking are often set in far-away places, like cities in Cambodia, small towns in Moldova, or rural parts of Brazil. But human trafficking happens in cities and towns all over the world, including in the United States. Enslaved farmworkers have been found harvesting tomatoes in Florida and picking strawberries in California. Young girls have been forced into prostitution in Toledo, Atlanta, Wichita, Los Angeles, and other cities and towns across America. Women have been enslaved as domestic workers in homes in Maryland and New York. And human trafficking victims have been found working in restaurants, hotels, nail salons, and shops in small towns and booming cities. Wherever you live, chances are some form of human trafficking has taken place there. 5 THIN GS TO KNOW

- 11. 9 3. It’s happening to people just like you. Human trafficking doesn’t discriminate on the basis of race, age, gender, or religion. Anyone can be a victim. Most of the human trafficking victims in the world are female and under 18, but men and older adults can be trafficking victims too. While poverty, lack of education, and belonging to a marginalized group are all factors that increase risk of trafficking, victims of modern-day slavery have included children from middle- class families, women with college degrees, and people from dominant religious or ethnic groups. 4. Products you eat, wear, and use every day may have been made by human trafficking victims. Human trafficking isn’t just in your town—it’s in your home, since human trafficking victims are forced to make many of the products we use everyday, according to ProductsofSlavery. org. If your kitchen is stocked with rice, chocolate, fresh produce, fish, or coffee, those edibles might have been harvested by trafficking victims. If you’re wearing gold jewelry, athletic shoes, or cotton underwear, you might be wearing something made by slaves. And if your home contains a rug, a soccer ball, fresh flowers, a cell phone, or Christmas decorations, then slavery is quite possibly in your house. Human trafficking in the production of consumer goods is so widespread, most people in America have worn, touched, or consumed a product of slavery at some point. 5. We can stop human trafficking in our lifetime. The good news is not only that we can end human trafficking around the world, we can end it within a generation. But to achieve that goal, everyone needs to work together. Already, activists around the world are launching and winning campaigns to hold governments and companies accountable for human trafficking, create better laws, and prevent trafficking in their communities. You can start a campaign on Change.org to fight trafficking in your community. You can also fight trafficking by buying from companies that have transparent and slave-free supply chains, volunteering for or donating to organizations fighting trafficking, and talking to your friends and family about the issue. Together, we can fight human trafficking … and win.

- 12. 10 STOLEN VOICES, BY BIDISHA Bidisha is a writer, columnist, critic and BBC radio and TV broadcaster. She specialises in the arts and culture, social justice issues and international affairs and is the author of two novels, an Italian travelogue and a Middle Eastern reportage. She writes regularly for the broadsheets in the UK and internationally and has judged numerous literary prizes including the Orange Prize, the John Llewellyn Rhys Prize, the Comment Awards and the Polari Prize. Her fifth book, about asylum seekers and refugees, will be out in May 2014. She has just been made a trustee of the Booker Prize Foundation. She is currently writing her sixth book, a novel called Transformation Play, and doing outreach work in prisons. STOL EN VOIC ES They told me they’d go back to my country and kill my family. “

- 13. 11 “The police didn’t believe that the trafficker had raped me. He told them he was my boyfriend and they believed him. And then they accused me of being a trafficker because they said another woman [who had been trafficked]hadtoldthemIwas.” STOL N VOIC ES

- 14. 12 “He raped and trafficked dozens of women and they only gave him two years in prison, of which he served half.” “They had [our daughter] there in a flat and said she was fifteen, not twelve. We had to drive around looking for her and they blocked off the road with their cars so we couldn’t drive down in. When we told the men we’d call the police they went around the neighbourhood putting up pictures of her, with her phone number, and we got hundreds of calls from men wanting her services. When we told the police they told us she’d gone with the men through her own choice.” “The police put me in prison for six months for being here illegally when it was me who was kidnapped, trafficked and raped.” STOL N V IC S “I pitched a TV series about trafficking, based on my experiences working with trafficked women, and the executives didn’t commission it because they said trafficking didn’t exist.” “The journalist asked me, ‘Were you frightened when you were raped and tortured? Were you frightened?’ A very famous, well-respected journalist. I had to explain to him, gently, that’s not what you say to a woman who’s a survivor. Not in that tone—wanting to be titillated by the answer and enjoy the woman’s pain. That is not the way to ask a question.”

- 15. 13 These quotes have haunted me for several years. They are from women who have been trafficked, women who help survivors of trafficking and those who investigate, research and challenge trafficking all over the world. At the events at which these women speak, we have to be very careful: we protect identities, use pseudonyms, ban photographs and film footage in case the traffickers extract revenge, come and find the women, sabotage the investigations in the most brutal, violent and thuggish ways. What I have learnt from these powerful, distressing meetings and from unforgettable plays like Cora Bissett’s Roadkill, is that trafficking, like all abuses of women, is common, not rare; accepted, not underground or taboo; international, not local; systematic, not exceptional; organised, not ad hoc. Trafficking, like all sex abuse, is mainstream. In 2009 the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime concluded that 79% of trafficking is for sexual exploitation. The report covers 155 countries. To traffic women is to be part of a vast, complex and well-factored international crime process which turns women into commodities and trades them, against their will, consent, dignity and knowledge, just like drugs, dirty money, weapons and contraband goods are traded. This is done with the full knowledge and sometimes with the collusion of non- criminal organisations and networks including the police, politicians and local businesses. Trafficking involves extreme coercion (sometimes by older women offering younger women domestic or secretarial work abroad); grooming, intimidation and pressure; outright kidnapping; detention and deception; removal by force within or across countries; repeated severe beating, gang rape and other torture to break a woman mentally and physically; the loss of all markers of humanity including a woman’s name, clothes, language, money and personal items; sale, trade and rape between gangs of pimping men; being held hostage in a room or house or brothel, often in a completely alien country whose name or language they may well not know; the (realistic and true) threat of torture and murder if a woman tries to escape; and then usage, which is nothing more than rape, for weeks and months and years, by johns, punters, users, exploiters and other ‘ordinary guys’ who think it’s okay to rent and use a woman’s body for their own momentary gratification. “I was interviewing women who’d been trafficked. The TV was on and there was a famous telly chef on screen. The women freaked out because he was a client. In his public life he’s a patron of a domestic violence charity.” S OL N IC S

- 16. 14 I was visiting my boyfriend and then some men came in a van and took me away. “ OL I S

- 17. 15 I am not exaggerating any of this and my words are nothing compared to the bodily, emotional and mental trauma experienced by the hundreds of thousands of girls and women who experience it. To fully acknowledge the extent and harm of trafficking, we must face the world’s harshest abuses, deepest hypocrisies and most long-standing inequalities. We must be ready to confront the ugliest realities, brutal personalities and violent processes. Pioneering journalist Lydia Cacho’s recent book, Slavery Inc: The Untold Story of International Sex Trafficking lays out in shocking and moving detail the extent and depth of this global problem, its endemic features and its interconnection with many other kinds of international trade. It makes for aggrieving reading, and although there are countless organisations, like the Poppy Project in the UK and Aapne Aap in India, which help survivors of trafficking, too many people look away, cannot face reality or minimise its gravity. In many ways the ‘untold story’ of trafficking is echoed in the stereotypes and practices of all the other parts of society. We must be brave and self-critical enough to recognise that the misogynist values and systems which underpin trafficking are echoed far beyond its networks. Whenever women are abused, the tendency is to blame, vilify and punish the victim and excuse the perpetrator. When a perpetrator is punished—for rape, for murder of a partner, for stalking, for harassment, for abuse—any penalisation enforced by the courts is markedly lenient. The police, the media, the judiciary, are passive, unenlightened, and unconcerned. When a woman is exploited for sexual and other labour we talk about how she ‘chose’ to do it, instead of realising that a choice made in the face of threats of violence, extreme poverty, blackmail, shame, fear, extreme inequality, is no choice at all. At the heart of the complexity is something very simple: a woman is a human being and not an object. The many survivors I have spoken to are the strongest human beings of all. O S “An investigative journalist for [a major UK broadsheet] said he’d researched trafficking and learnt that figures of trafficked women were grossly exaggerated. We contacted the main charity which helps trafficked women in the UK. They said they hadn’t been contacted by him.”

- 18. 16 RESTORING CONFIDENCE, ENVISIONING THE FUTURE Preface Envisioning the future can be hard, when trying to overcome the past. In addition to the visible scars that can serve as a reminder of physical abuse, women who survive sex trafficking often carry invisible emotional and spiritual scars. Feelings of self-worth and dignity built up through adolescence can be demolished in seconds and can take a lifetime to rebuild, and yet somehow survivors find the courage and confidence to hope for a better life, to imagine themselves as they deserve to be— healthy and happy. The British Council was privileged to work with two recent graduates of Restore NYC’s sex trafficking rehabilitation program. These remarkable women were treated to a makeover by a team of stylists and a celebrity photographer to help restore their confidence and inspire them to pursue their career dreams. Restorin g conf iden ce, envision ing the futu re

- 19. 17 wanted to be a hair stylist when she was a girl, but she was trafficked from Honduras to the United States at the age of 17. She was romanced by a man who said he loved her but was in fact part of an organiza- tion that trafficked vulnerable girls and women. Before she came to Restore, she was in a psychiatric ward before the FBI asked if Restore could provide a home and services to her. She now has a job, has made great progress learning Eng- lish, and would like to own a big restaurant one day. “A” Restorin g conf iden ce, envision ing the futu re

- 20. 18 had dreams of becoming a veterinarian when she was younger, but she was trafficked from Mexico to New York by a criminal organization. She always dreamed of having a big family and loving husband and for the first time in many years thinks that this can indeed be true for her. She is not sure exactly what she wants to do long-term but is very happy right now with her job in the food services industry—and the apartment she is about to move into. “L” Restorin g conf iden ce, envision ing the futu re

- 21. 19 Restorin g conf iden ce, envision ing the futu re Jimmy Lee is the Executive Director of Restore NYC Restore NYC’s mission is to end sex trafficking in New York and restore the well-being and independence of foreign-national survivors. Long-term, safe housing is a critical gap in the aftercare of survivors. A late-2011 study by Hofstra University states that 87% of trafficking victims in New York are in need of long-term housing but only 4% actually find it. The Restore safehouses are the only such facilities in the region that provide long-term housing for foreign-national survivors. Though our plan is that each survivor successfully transition in 12 months, we do not have a hard-and-fast rule and a number of our safehouse women have stayed for as long as 15 months. These homes are essential to the healing and successful future of many survivors. If a survivor is not able to be placed in our safehouse, she is usually referred to a short-term (60-90 day) shelter focused on victims of domestic violence. In the worst case scenarios, some survivors actually go back to the only source of housing that they have known—that provided by their trafficker. Restore safehouses are designed to build community, foster healing and develop life skills so that each survivor will transition to a healthy and independent life. In addition to customized plans to bring healing and hope to each survivor, we provide ESL courses (both group and individual), yoga and art therapy, professional counseling, GED preparation, financial literacy training, job-readiness programs, and placement into part- time jobs with trusted businesses. We also bring in committed volunteers to cook meals or take survivors out for a movie—to be sisters and family to each safehouse woman. Each survivor will also have a mentor (“big sister”) that walks alongside her during her time in the safehouse and after she graduates. This mentor will do everything from accompany her to appointments, help her with homework, be an informal counselor and friend, and help her think about her future. You can learn more about Restore NYC by visiting their website http://restorenyc.org/

- 22. 20 Siddharth Kara, Fellow on Human Trafficking, Carr Center for Human Rights Policy, Harvard Kennedy School; Fellow on Forced Labor, FXB Center for Health and Human Rights, Harvard School of Public Health 1. The public (government) and voluntary (non-profits) sectors are hard at work on this issue, how might the private (businesses) sector with its resources and convening power further strengthen the anti-trafficking movement? The business sector has a vital role to play in combating human trafficking around the world. The fact of the matter is, countless global supply chains are tainted by various forms of modern-day slavery, and there is very little awareness of the extent to which these supply chains are tainted, let alone how they might be reliably cleansed. Countless products that we purchase every day may have supply chains that stretch to the far corners of the world, where severely exploited labor might be used at various stages in the production process. Supply chains that I have personally documented that are tainted by slave-like practices for products sold in the U.S. include: rice, frozen shrimp, tea, coffee, hand-woven carpets, apparel, granite, cubic zirconia, and others. The corporate sector must take a more aggressive stance in acknowledging these issues, supporting research to document and analyze the extent of problem, and invest in reliable and sustained cleansing and certification procedures. Doing so will allow consumers to make fully-informed choices about purchasing products that are free of human trafficking, forced labor, and child labor. Tracing Tea / Shutterstock.com 3hree questi ons

- 23. 21 2. How are governments like the United States assisting international NGOs or putting pressure on foreign governments in countries of origin and destination where corrupt officials actively facilitate trafficking abuses? The U.S. government is a global leader in advancing more effective efforts to combat human trafficking. Through its Office to Monitor and Combat Human Trafficking, the U.S. Department of State supports research, awareness campaigns, and others activities intended to elevate the global response to human trafficking. The U.S. government also engages in important diplomatic and policy efforts around the world relating to human trafficking. Several other U.S. government agencies, such as the Department of Labor, the Department of Homeland Security, the Department of Justice, and others also all play important roles in combating human trafficking. In addition, the U.S. Trafficking Victims Protection Act and its four reauthorizations are a model for national legislation on human trafficking. In many countries, the issue of corruption is a particularly complex one, from the police, to border patrol, to the judiciary, and effecting real change in the near term remains a challenge. Having said this, progress has certainly been made on the issue of corruption in many of the countries that I have visited. While much remains to be done by the U.S. Government and other governments to tackle human trafficking more effectively, especially as relates to providing greater resources and increased international cooperation, the U.S. Government is certainly a global leader as far as current efforts are concerned. 3. How has the global economic downturn affected the human trafficking industry? This is an interesting question. There is limited data on the issue of how the recent global economic downturn has affected levels of human trafficking around the world, but there is certainly a general sense that the downturn has exacerbated the issue. In many cases, the downturn led to increased vulnerability of already-vulnerable populations, which in turn precipitated increased desperation to find income-generating opportunities. Traffickers and other exploiters capitalized on this desperation to acquire new victims in a plethora of sectors. Promises for reliable wages or other opportunities to migrate for a better life have turned into one-way tickets into outright exploitation. At the same time, the global economic downturn has also meant that many consumers in developed economies have needed to cut expenses. One way of doing so is to purchase the less expensive version of products. In many cases, these low-cost products are produced through some degree of labor exploitation, which in the extreme can be slave-like in nature. Increased demand for low- cost products has in turn stimulated demand by producers to cut costs of production, and labor is a prime means of doing so. Thus, on both sides of the equation (production and consumption) the global economic downturn has exacerbated levels of human trafficking, though it would be very useful for the field to have a more reliable sense of exactly how, why, and to what extent global economic downturns impact levels of human trafficking. The same must be said of other large-scale catastrophes, such as military strife and environmental disaster, each of which is almost always a harbinger of significant increases in human trafficking from the affected areas.

- 24. 22 CAASE: ENDING HARM, DEMANDING CHANGE IN CHICAGO AND BEYOND Rachel Durchslag, Founder of the Chicago Alliance Against Sexual Exploitation (CAASE) I never would have imagined that a film could change the course of my life, but in 2003 I watched a film about human trafficking, and something inside of me changed. I learned that day of an injustice so profound that I had a hard time imagining the subject of the film could be true. I almost could not believe that women were being sexually enslaved in the 21st century. When I got home, I could not stop thinking about what I had seen. The idea of someone being forced to endure sexual exploitation, while someone else profited, was unfathomable. When I learned that human trafficking was not only taking place internationally but also here in my home, I knew I needed to take action. In order to really understand the issue, I wanted to get out of my comfort zone and work with victims abroad. In 2004, I traveled to both Thailand and India to work with young children who had been kidnapped and sold by their families into sexual slavery. Seeing the faces of these young people transformed me, and hearing the stories of what they had endured inspired me to make ending sexual exploitation my life’s work. This became the spark for creating the Chicago Alliance Against Sexual Exploitation, or CAASE, a nonprofit dedicated to ending the perpetration of sexual harm. When working on CAASE’s mission, I thought back to my time abroad. I remembered the girls I met, many of whom had scars covering their bodies from their ordeals. I visualized the child who had been set on fire by her trafficker. And the other girl whose body bore knife marks that covered all of her exposed skin. And then I thought about the faces I hadn’t seen—those of the men who had sexually exploited these girls and robbed them of their childhoods. I knew that as long as men were willing to buy sex, creating demand, the sex trade would continue to flourish. Without addressing demand, people would continue to be harmed. The sex trade industry is one of the ugliest manifestations of harmful human interactions. It occurs both internationally and domestically. Many of us have heard about international trafficking. Information and depictions of sex trafficking have begun to appear in our movies and public awareness campaigns. The United Nations helps us contextualize the extent of the problem by showing how trafficking is now the second largest money-making venture in the world, and that it nets organized crime more than $12 billion a year. pictured Mercy Ojelade and John Kazek END ING HARM,

- 25. 23 Trafficking is a gruesome reality. It is the buying and selling of human beings through force, fraud or coercion. Traffickers are strategic business people. They search out the most vulnerable individuals and entrap them in the sex trade through promises of jobs, education, or a relationship. So what does sex trafficking and sexual exploitation look like in our own community? In Chicago alone, between 16,000 to 25,000 women and girls are impacted by the sex trade industry on any given day. Many Americans still fail to grasp the severity of the problem on a national and local level. This is in part due to the clandestine nature of prostitution, which largely takes place indoors and away from the public eye: in strip clubs, in hotel rooms, in massage parlors, and in brothels. In Chicago alone, between 16,000 to 25,000 women and girls are impacted by the sex trade industry on any given day. Our society also accepts the sex industry and glorifies pimping and prostitution. The word “pimp” is now used to describe everything from juice, to cars, to parties at clubs, to baby clothes. We have elevated this particular type of perpetrator to celebrity status. And the more we look at pimps as glamorous, the more the harms experienced by sexually exploited women and children go both unnoticed and unaddressed. Many people do not understand prostitution and sex trafficking as a pervasive form of violence against women. Instead, prostitution is seen as a choice, or even a legitimate career. Many who hold these beliefs are unaware of the harsh and profoundly disturbing realities of the sex trade for the vast majority of those who are in it. While prostitution is an issue that impacts people of all ages, homeless youth are especially vulnerable. In Chicago, one study shows that the average age of entry into prostitution is 16. According to the National Center for Missing and Exploited Children, one out of every three teens on the street will be approached to be recruited into prostitution within 48 hours of running away. Homeless youth, many of whom have fled abusive homes, are often coerced into prostitution out of dire emotional and financial circumstances. With all the harms and injustices faced by those in the sex trade, there are very few resources that exist to help people exit prostitution. In Illinois there are no residential programs created specifically for adult survivors of the sex trade, and only eight beds for prostituted youth. We lack other needed services for prostituted individuals such as substance abuse treatment, domestic violence programs, and employment opportunities. Creating resources to meet the needs of prostituted individuals is essential, but this is only one piece of the solution. The other piece is both simultaneously simple and complex: we must address the root cause of the issue—the demand, predominantly from men, to purchase the bodies of women and children. CAASE’s work focuses on addressing this root cause. Our legal services, advocacy, prevention and community engagement are all focused on holding perpetrators of sexual harm accountable for the harm they cause. We offer free legal representation to survivors of sexual assault and the sex trade. We are passing laws and influencing policy to hold pimps, johns and traffickers accountable. We are teaching young men about the realities of the sex trade, with the goal to prevent them from becoming patrons. And we are encouraging community engagement around these issues through the arts. To learn more about our efforts, please visit www.caase.org DEMAND ING CHAN GE

- 26. 24 FIVE WAYS TO STOP HUMAN TRAFFICKING AND SEXUAL EXPLOITATION 5IVE WAY S TO S TOP EDUCATE YOURSELF Learn to recognize the signs that someone might be a victim of trafficking: http://www.polarisproject. org/human-trafficking/recognizing- the-signs. If you believe someone is a victim of human trafficking, contact the National Human Trafficking Resource Center Hotline at 1-888-3737-888. FOCUS LOCAL Sex trafficking would not exist were there not a demand to purchase the bodies of victims. Find out about what your city is doing to suppress demand at: www.demandforum.net. Sign up for action alerts at change.org so that you can support future initiatives to end human trafficking. LEND A HAND Volunteer your time or professional expertise by contacting a local advocacy organization to see how you can help. For example, if you are a lawyer, you can provide pro bono services to trafficking survivors. Find out about organizations in your state working to end sex- trafficking by visiting: http://caase.org/our-alliances. DONATE Survivors of human and sex- trafficking are frequently in need of clothing and other donations. Contact local organizations to find out what donations they can accept. SPREAD THE WORD Though there recently has been more media attention regarding issues of human trafficking, many people remain unaware of this human rights violation. You can host book clubs, film screenings, utilize activist toolkits, and create other projects to raise awareness. But I’m just one person, what can I do? Contributed by Rachel Durchslag, founder of the Chicago Alliance Against Sexual Exploitation (CAASE)

- 27. 25 A PATH TO SERVICE I am so thankful for the road I once thought was broken, to now be a gateway to those greatest in need. A PATH TO SERVICE Photo: Jessica Minhas (left) with Samana, a survivor who is part of the Voices for Change leadership program at the Somaly Mam Foundation.

- 28. 26 A PATH TO SERVICE Jessica Minhas is a speaker, journalist and producer on social justice activism, abuse, and sex trafficking. Jessica is on the team of the Blind Project. The Blind Project is a collective of passionate individuals uniting together, leveraging their unique talents to empower victims and survivors of the commercial sex trade in Southeast Asia. Learn more at www.theblindproject.com I have been working in the human rights field for over ten years. I started young—when I was 19. I guess you could say I am an accidental humanitarian, though I’m not sure if there is such a thing. I think social injustice work finds you, rather than you finding it. The truth of the matter is, fighting for the rights of those who are vulnerable has so profoundly impacted my life that I often have to stop and ask myself, “How did I become so blessed?” I was raised in the South by just my single white grandfather. We found ourselves in this predicament after my biological parents abandoned my identical twin, Jennifer and me when we were six months old. It was then that my maternal grandparents courageously stepped in and accepted custody of us, despite being well into their retirement. Just a few short years later, when Jennifer and I were nearly three years old, we were involved in a deadly accident that claimed her life. As a way to cope, I believe, my grandparents succumbed to an exponentially aggressive alcohol addiction that would eventually contribute to my grandmother’s death when I was nine years old. My grandfather’s erratic anger towards me, likely out of his own deep pain and grief, worsened my ability to navigate the chaotic and terrifying household I found myself in. Left alone, my aging grandfather did his best to commit his life to me to ensure my future, but the sad reality was we were now by ourselves, and his alcoholism had become both unpredictable and violent. As a 4th grader, I was now expected to fulfill the roles my grandmother had as ‘lady of the house’. Cook, maid, emotional confidant and scapegoat were now duties that replaced any sense of normalcy in my childhood. My grandfather’s erratic anger towards me, likely out of his own deep pain and grief, worsened my ability to navigate the chaotic and terrifying household I found myself in. Many times I expressed my fear and growing understanding that what I was experiencing at home was not actually supposed to be a part of anyone’s childhood. I frequently went to my teachers, counselors at school, friends’ parents and neighbors asking for help, but was met with a display of empathy, but an overwhelming unwillingness to intervene on my behalf. Gradually, I learned that I was powerless to stop the emotional and physical abuse at the hands of my struggling grandfather. Feeling isolated, alone, and trapped, I suffocated for years under the weight of depression and thoughts of suicide. When I was 15, my grandfather fell gravely ill, and our care-giving roles reversed. His life was now placed in my hands. In between high school academics, cross-country practice and play rehearsal, I tried my best to care for him on my own. He survived long enough to see me turn 18, and graduate from high school, though I’m not sure how. Just a few weeks after my graduation, he passed away. I was left an orphan. A PATH TO SERVI CE

- 29. 27 For a long time I resented my childhood and everything that had happened. I was angry- at myself, and at those around me. I couldn’t make sense of all of those years of abuse and what the reason was. Yet, deep within me a strong desire to someday find some resemblance of a family motivated my commitment to search for my biological Indian roots. When I was presented with the opportunity to serve in India and Nepal with one of my best friends in college, I immediately said ‘yes’. On route to Nepal, we passed through Calcutta and volunteered at an orphanage for children age 16 and under. When I innocently asked what happened to the girls when they aged out of care at 16, the staff responded that unless they were married, or were fortunate enough to find work, they would likely be forced into sexual exploitation. This was the first time I had ever heard of the commercial sexual exploitation of children. To me, it was criminal for this small percentage of children rescued off the street, to later face such desperation that only selling themselves would enable their survival. I couldn’t understand who would want to have sex with a child or how such an atrocity could even happen in a modern world. That single moment at this orphanage in Calcutta changed me. Looking back, I see clearly how my greatest suffering has, in fact, become my greatest blessing. My own struggles have given me a deep understanding, tenderness and empathy for the poor, the stranger, the orphan and the widow. I soon learned an overwhelming majority of sexually exploited youth are runaways or castaways from dysfunctional homes where they have suffered physical, psychological and sexual abuse. I realized any one of those children could have been me. I was just as vulnerable; I too lacked a strong family and any source of support or encouragement. I was fortunate enough to have access to an education and to have never encountered a pimp who could have coerced me into prostitution. Still, in a very small way, I saw pieces of myself in the stories of Calcutta’s victims. I could empathize because I shared the same feelings of being forgotten and used. I remembered screaming for help and having my cry, just like theirs, go unnoticed. Suddenly, the resentment I carried for so long turned into a righteous indignation and fiery passion to help those trapped in sexual slavery. The tragedies of my childhood are incomparable to the atrocities these children in Calcutta and many others around the world face, but our shared vulnerability and helplessness drives me to fight for them. I was exposed to the world of child sex slavery and I decided I would never turn away. Looking back, I see clearly how my greatest suffering has, in fact, become my greatest blessing. My own struggles have given me a deep understanding, tenderness and empathy for the poor, the stranger, the orphan and the widow. I am so thankful for the road I once thought was broken, to now be a gateway to those greatest in need. I have learned that it is in the places where our hearts are broken, that we cultivate our ability to serve others and love well. This is my story, but what is yours? Where is your heart broken? What gives you a righteous indignation? What gives you joy? What makes your heart come alive? Find this, and you will find your truest self, and in doing so bring hope to those without justice, community and reconciliation. A PATH TO SERVI CE

- 30. 28 YOUR SLA VERY FOO TPRINTMEASURE YOUR SLAVERY FOOTPRINT Go to slaveryfootprint.org to find out how many slaves work for you! The average person doesn’t comprehend his or her connection to modern-day slavery. Slavery Footprint helps map consumers’ connections to modern-day slavery by measuring their impact based on lifestyle choices—including everyday items they purchase or own such as food, clothing, medicine, and electronics. Slaveà Raw Materialsà Manufacturerà Brandà YouHow do you measure up?

- 31. 29 The Business Consultant (male, age 37) New York 28 slaves The Nurse (female, age 26) Florida 46 slaves The Electrical Engineer (male, age 25) San Francisco 52 slaves The Attorney (male, 63) Houston 25 slaves The Graphic Artist (male, age 47) Los Angeles 81 slaves The Teacher (female, age 31) Atlanta 64 slaves The Tech Industry Executive (female, 53) Minnesota 98 slaves The Stay-at- Home Mom (female, age 32) North Carolina 35 slaves Here is a random sample of people from across the United States. YOUR SLA VERY FOO TPRINT

- 32. 30 Chal lenge Slavery Tec h Con test SPOTLIGHT: CHALLENGE SLAVERY TECH CONTEST The United States Agency for International Development (USAID) partnered with anti- trafficking organizations Free the Slaves, Not For Sale, Slavery Footprint, MTV Exit, and Abolition International for the Counter-Trafficking in Persons (C-TIP) Campus Challenge Tech Contest. Thousands of students from around the world were asked to come up with a creative technology solution to help further prevention and protection. The winners were announced at the end of March 2013, and were invited to share their proposals with donors, counter-trafficking organizations and technology professionals. WHO:The first-place winners of the Campus Challenge Tech Contest are Virginia Tech’s Wes Williams, Kwamina Orleans-Pobee and Nick Montgomery. WHAT:The team’s online intervention tool AboliShop, which is a browser extension for Google Chrome, makes information about the slavery impact of items available for purchase—based on Not For Sale’s Free2Work ratings—accessible to Amazon.com’s shoppers. Consumers can set their own search standards to prioritize ethically sourced and manufactured products or can opt to purchase more socially conscious products in categories like apparel and electronics based on the application’s product grades. See the AboliShop demo here: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ADP04eXQLq8

- 33. 31 Chal lenge Slavery Tec h Con test The British Council asked the team a few questions about their winning project: Q: In a world where people troll the web to find the best deal on a particular item or comparable products,WHY do you think consumers will choose the ethical purchase over the unethical purchase, even if the socially conscious choice might be more expensive? A: Many consumers have proven over the past few years to be interested in the social impact of their purchases, and we think that the primary reason we haven’t seen a similar movement with slavery-aware consumerism is a lack of information. Abolishop seeks to remedy that. When consumers can see exactly how their choices are aiding or combatting modern day slavery, they are empowered to make a difference. While some may continue to make purchases based only on price, we feel that the majority will recognise that a few dollars is not worth perpetrating the slavery of another human being, and will shop accordingly. In addition, these purchases are often not a matter of major price differences. Many of the products that are bought with such low grades actually have better graded alternatives at a similar price point. We really think the utter lack of information, especially information provided with such proximity to the act of shopping, is the primary reason consumers haven’t been affected. Q: HOW might this application affect 1) e-tailers that don’t offer customers access to ethically sourced brands 2) manufacturers that might not be concerned with debt-bondage or wage theft in supply chains? A: We hope that the effect is a simple one: it hurts their profits. With the power of our alternative recommendations in hand, which is one of the features of AboliShop, consumers will be able to move easily toward rewarding companies that do offer ethically sourced products and away from those that are apathetic to this fight. We want to put monetary pressure on any and every corporation that is actively ignoring the plight of modern day slavery. We want it to be ethically laudable, but also distinctly profitable, to care about your supply chain.

- 34. ‘FUS RO DAH’ 32 ‘FUS RO DAH’ Sarita, a survivor of international human trafficking. I am woman torn from home, from all that was known. I was a child in innocence, lost at their hands. I was mother, sister, daughter, cousin, friend .... all gone. But through it all I never gave up. The pain, the fear, the unknowing. The starvation, separation and threats. The rapes, the bleeding, hope lost. They took my children away from me. But I am the Unrelenting Force. This, they did not know as they targeted me. It is impossible to silence, to hide, to still. Each day the voice grows stronger ready to shout. And through it all I never forgot me. I prayed every night for this ordeal to end. But every morning I awoke to more cruelty. My children fed lies more often than food. Keeping lies out through family bonds. The Force grows stronger from the pain inflicted The Balance in my mind fights to remain sane. The Push to find a way out steadily takes shape. In spite of it all I found strength anew. A moment of clarity now and then. A plan of escape, I’m smarter than them. I watch and listen and take the chance. Twenty minutes can feel like forever.

- 35. 33 Time ticking no clock seen, routines copied and secrets seen. The hope leads to this, the moment, the one chance I get. A phone, no signal is all lost again? Wait, static, static is all I can hear. A message left in desperation, then wait and hope, time running out. My Voice is raw power, pushing aside anything - or anyone - who stands in my path. The desire for freedom, the need to escape, the prayers for this to be taken away. Building, building, growing stronger, growing braver, welling up inside until. The escape plan formed, the rescue made, the silence shattered. The voice speaks out, the voice is known. As the voice grows stronger the fear of the captors is seen. Chasing through states, burning bridges with haste. The police, the questions, the asking for proof. The shelters, the running, the hiding, the fear. Following every movement made, traffickers pursue. They think they are smart but they are not smart enough. But I am the unrelenting force. The journey is not complete when the rescue takes place. Held captive with no rope, no chains, no end in sight. Threats against children, starvation and sleep deprivation. Feed their ego, lack of morals, their thoughts not of human. To speak out now gives the woman new hope. To speak out now gives the children a voice. To speak out now helps others understand. This can happen to you.

- 36. Join the conversation as it unfolds on the Roadkill Forum: http://usa.britishcouncil.org/art/roadkill. Follow us on Twitter (@usaBritish and #Roadkill13) and Tumblr (#Roadkill13) Susan Feldman and Andy Hamingson of St. Ann’s Warehouse, Criss Henderson and Kendall Karg of Chicago Shakespeare Theater, Cora Bissett, Richard Jordan, Tim Morozzo, Rachel Durchslag of Chicago Alliance Against Sexual Exploitation (CAASE), Leif Coorlim of CNN Freedom Project, Veronica Zeitlin and Emilie Yam of USAID, Norma Ramos of the Coalition Against Trafficking in Women, Sara Elizabeth Dill, Ruth Lewa of Solidarity with Women In Distress (SOLWODI) Kenya, Kate Mogulescu of Legal Aid Society, Vivian Huelgo and Laurel Bellows of the American Bar Association, Jimmy Lee of Restore NYC, Robert Rigby-Hall and Dawn Conway of the Global Business Coalition Against Trafficking, Siddharth Kara, Debra Brown Steinberg of VS: Confronting Modern Slavery in America, Baroness Mary Goudie, Lyn Gardner, Bidisha, Jessica Minhas of the Blind Project, Chipo Nyambuya and Alison Cline of the British Consulate in Chicago, George Kogolla of British Council in Kenya, Anne Milgram, Heather Gregorio, and Nancy Hoppock at NYU Law, Matthew Windrum of the British Consulate in New York, Craig Longhurst and Greg Ruggeri of Ruggeri Salon, Harley DeOliveira, Daniela Federici, Aaron Cohen, Alyse Nelson of Vital Voices, Mai Shiozaki of the Office to Monitor and Combat Trafficking in Persons, Jody Raphael from the College of Law at Depaul University, Kaitlyn Soligan of Madre, Amy O’Neil Richard at the U.S. Department of State, Wes Williams, Jennifer Chan at the U.S. Fund for UNICEF, Tracy Francis of New York Foundation for the Arts, Ken Karlic of Splice Design Group, and Brooklyn Borough Hall. SPEC IAL THANKS