What Urban Forests are - chapter 1

- 1. 1 WHAT URBAN FORESTS ARE

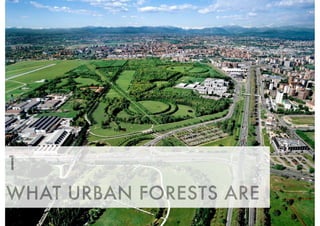

- 2. Urban green areas can be divided into several categories depending on the size of the spaces, or the function they carry out in the gre- en envelope of urban and suburban areas. A first large division must be carried out between public and private spaces. The major difference between these two categories is lin- ked to usability and access. In fact, and with several exceptions, it is quite clear that private spaces offer citizens less opportunities of usability compared to a public space where the main objective of the population is its utilization. Another major difference between these categories is linked to the management. With private spaces, in situations of great value and likewise control of management by a public purse, interventions can only be carried out through an authorization mechanism of the works that could modify the consi- 8 DIFFERENT TYPOLOGIES OF GREEN SPACES IN URBAN AND PERIURBAN AREAS 1.1 RICCARDO GINI

- 3. stency and the more invasive maintenance work such as the pru- ning of large trees. This would lead to a difficulty in the manage- ment of private green spaces that often propose solutions which tend to block the view from the outside, therefore not allowing a visual usability. (www.comune.torino.it/verdepubblico/patrimonioverde) When private spaces become part of a new allotment it should be possible to plan them out in continuity with the public spaces by ensuring, regardless of the limitations linked to the accomplish- ment of the above mentioned, a territorial unicum that could create urban ecological networks; in fact even private spaces, for their impact in terms of landscape and environment, contribute to the territorial quality of a location. In order to accomplish this, a sort of mechanism of rewards may be necessary if the planning and management of public and private spaces is carried out in continuity and in a shared manner. Analyzing the categories that characterize urban public greenery, a first distinction based on the surface may be made between urban parks, neighborhood gardens, tree rows, median hedges, flower beds and green fixtu- res. As a matter of fact, there are many more possible types of ur- ban greenery, but we will limit ourselves to the main types. (http://www.paesaggio.net/verde.htm) An urban park is large enough to adopt a nature, though it usual- ly originates from artificial plantations, which can provide leisu- re and relaxation to its citizens. In addition to size, its degree of consistency is also important. It must be such as to allow one the perception of exiting an urban fabric to being immersed in an oa- sis of nature. A neighborhood garden instead performs other functions that are more linked to urban social life. In terms of an urban plan, it is perceived as an endowment of the city in support of urbaniza- tion. Its dimensions vary depending on the neighborhoods and almost always contain light equipment for playing and leisure ac- tivities that would promote socialization among citizens. The use of these spaces, especially if they are of small dimensions, is qui- te rigidly regulated. 9 1 - WHAT URBAN FORESTS ARE www.emonfur.eu

- 4. The tree rows alongside the roads, in addition to their function of shading so as to avoid overheating, and improvement in terms of landscape so as to provide a pleasant promenade for pedestrians on adjacent sidewalks, ecologically constitute a line of continuity and penetration of nature in the urbanized fabric. In terms of air pollution, the ability of plants to retain dust particles, pollutants and act as a barrier to their diffusion contributes to the improve- ment of air quality. Median hedges and flower beds are essentially a function of street fixtures with aesthetic value and traffic order. In terms of the allocation of urban area greenery their contribution is rather limited when it comes to usability, but is considered more effecti- ve when it comes to enhancing certain locations of a city. Urban gardens must also be included to the types of urban area greenery analyzed thus far (see the Boscoincittà Box by Paola Pirelli), which carry out functions that are almost entirely social and do not have a particular impact on the ecological plot of ur- ban areas. Gardens are in fact small plots of family farming who- se functions are mainly to facilitate the socialization of citizens, and in particular, those on the older end of the population, as well as contribute to the local production of vegetables for home consumption. As the consolidated fabric of a city becomes less compact and the open spaces achieve greater consistency more opportunities for new types of greenery will present themselves, where an ecologi- cal character will become even more pronounced and the transi- tion between the city and country will find a harmonious interpe- netration. An urban forest can play a decisive role with this type of greene- ry. A park with an important forest allocation, both of a natural type - the remains of nature before urban expansion (ex: Parco delle Groane www.parcogroane.it) - , and artificial - the result of a planning that accompanies urban development with that of na- ture (ex: Parco Nord Milano www.parconord.milano.it) -, is cru- cial for the realization of ecological networks and green infra- structures that are increasingly fundamental elements for the 10 1 - WHAT URBAN FORESTS ARE www.emonfur.eu

- 5. quality of urban life and environmental sustainability of our citi- es. (http://www.scirp.org/journal/PaperDownload.aspx?paperID=5 881) At this point in our analysis of the types of urban and peri-urban greenery, it is necessary to introduce two concepts that allow the idea of urban greenery to evolve from a “service or allocation” of the city to that of an infrastructure element in order to permeate inhabited space and nature in a unique and long-lasting balance. The two key concepts are ecological network and green in- frastructure. The first concept can be defined “as an interconnected system of habitats whose biodiversity needs to be safeguarded. Thus the focus goes on animal and plant species that are potentially threatened. In this case, the geometry of the network has a struc- ture based on the recognition of core areas, buffer zones and cor- ridors that allow the exchange of individuals in order to reduce the extinction risk of local populations. The EN is a tool aimed to mitigate habitats fragmentation and to ensure the permanen- ce of the ecosystem processes and the connectivity for sensitive species.” (http://www.isprambiente.gov.it/en/projects/ecological-networ k-and-terrritorial-planning?set_language=en) An ecological network introduces an important consideration: in order to discuss nature (and hence its permeability with urban fabric) we must discuss about interconnected systems, physically connected networks so that habitats that develop in the natural world may tend to achieve equilibrium without the continuous disturbances created by mankind. The concept of green infrastructures also extends to the use of the concept of an ecological network, with the addition of the importance of ecosystem services that nature offers mankind, in- serting in the conservationist policy a relationship of mutual be- nefit for the human species, which finds the source of its ecologi- cal equilibrium in the conservation of the habitats of animals and plants. 11 1 - WHAT URBAN FORESTS ARE www.emonfur.eu

- 6. “Green Infrastructure is addressing the spatial structure of na- tural and semi-natural areas but also other environmental fea- tures which enable citizens to benefit from its multiple services. The underlying principle of Green Infrastructure is that the sa- me area of land can frequently offer multiple benefits if its ecosy- stems are in a healthy state. Green Infrastructure investments are generally characterized by a high level of return over time, provide job opportunities, and can be a cost-effective alternati- ve or be complementary to 'grey' infrastructure and intensive land use change. It serves the interests of both people and natu- re.” (http://ec.europa.eu/environment/nature/ecosystems/) The definition of infrastructure in economic terms implies a long-term investment in the conservation or creation of natural networks, and a return of the benefits in the same amount of time so that it may ensure sustainable development to our conur- bations. Green Infrastructure (GI) is the network of natural and semi-na- tural areas, features and green spaces in rural and urban, terre- strial, freshwater, coastal and marine areas. It is a broad concept, and includes natural features, such as parks, forest reserves, hed- gerows, restored and intact wetlands and marine areas, as well as man-made features, such as ecoducts and cycle paths. The aims of GI are to promote ecosystem health and resilience, contribute to biodiversity conservation and enhance ecosystem services (Naumann et al., 2011a). GI is a valuable tool for addressing ecological preservation and environmental protection as well as societal needs in a comple- mentary fashion. One of the key attractions of Green Infrastructure is its multifunc- tionality, i.e. its ability to perform several functions on the same spatial area. A particularly categories of GI is the Urban Green Infrastructures. 12 1 - WHAT URBAN FORESTS ARE www.emonfur.eu

- 7. Green urban areas include any natural element in towns and citi- es that provide an ecological or ecosystem service function. This includes urban elements such as green parks, green walls and gre- en roofs that host biodiversity and allow ecosystems to function and deliver their services by connecting urban, peri-urban and rural areas. Of particular interest in urban environments will be the costs as- sociated with creating and managing new green areas with the aim of providing biodiversity or ecosystem service functions. The- se may include green roofs or new small non-domestic gardens in public areas. These are elements of more modern architectural and planning design and could provide interesting insights into the potential of integrating biodiversity into existing urban areas. (http://ec.europa.eu/environment/nature/ecosystems/docs/Gre en_Infrastructure.pdf) (http://ec.europa.eu/environment/nature/ecosystems/docs/im plementation.zip) (http://ec.europa.eu/environment/nature/ecosystems/docs/lan d_use_data.zip) 13 1 - WHAT URBAN FORESTS ARE www.emonfur.eu Click HERE to download the Italian version

- 8. URBAN VEGETABLE GARDENS (WHETHER SPONTANEOUS OR NOT) 14 PAOLA PIRELLI ORTI URBANI UNA RISORSA (URBAN GARDENS: A RE- SOURCE) is the title of a book that details a Ministry of Agriculture-funded study carried out by Italia Nostra in the 1980s on the subject of urban gardens. For over 30 years Italia Nostra-Centre for Urban Forestation (CFU) has dedicated resources to studying, designing and imple- menting urban gardens. City centre gardens fill an innate need for a return to the essential by being directly in touch with earth. It could be thought that urban gardening merely consists of collec- ting herbs, fruit and flowers that grow wild in open spa- ces, but it can become more organised and deliberate when taking over a small patch of land. BOX

- 9. Some grow vegetables or fruit, and others cultivate flowers: each to personal preference. Some prefer working on their own, while others like working in groups. These gardens in our cities often spring up in formerly abandoned and derelict pu- blic areas, and they reveal the creativity, individuality and cle- verness of people seeking a way to Nature. Defined “sponta- neous gardens” since they spontaneously emerge with little or no control by the local councils, a lack of coordination in how they are managed often leads to disorganisation, misuse and neglect, particularly when they cover large areas. Responding to this need to “get back to the earth”, many aut- horities and local councils have begun to consider regulating urban gardens and to include them in their system of public parks by redeveloping the existing spontaneous gardens and by creating new ones. The intention of the CFU was to satisfy a wish frequently expres- sed locally and provide a service for citizens. Themed green areas have been created for growing fruit and vegetables, indi- genous water plants, beekeeping, etc., and these are carefully and passionately maintained by the new ‘allotment holders’, areas that gain from the constant presence of people who fon- dly tend them, help to promote them and work hand in hand with the Park’s managers. The first project was when the City of Milan (with a population of 1,300,000) granted the CFU the public park Boscoincittà in 1987: 30 individual allotments with 3 common areas, each with tool-sheds and pergolas. Further urban gardens were desi- gned and created in Boscoincittà and in the Parco delle Cave in 1997 and the number of allotments now totals over 400. This idea was duplicated in 2011 by the municipality of Sesto San Giovanni that radically redeveloped an area of over 30,000 square metres which had been the site of spontaneous gardens for decades but was in a seriously neglected state. 15 1 - WHAT URBAN FORESTS ARE www.emonfur.eu

- 10. The method created and followed by the CFU, which has made it possible to transform derelict, marginalised areas into spaces of high aesthetic, cultural and social value, begins with a de- sign, followed by implementation and then continues with on- going management. The success of this method begins with designing and produ- cing a specific project to suit the context of the territory and ab- le to ensure sustainability and future maintenance by allotment holders. Key points in the project are deciding on the size of the allotments (generally ranging from 50m2 to 90m2), how to position the service buildings (sheds for storing tools) in a sing- le common area, the inclusion of common areas to encourage people to get together (with tables, areas for parties) and ascertaining possible alternative sources of drinking water (wa- ter tanks, use of underground water, etc.). Services could also be made available to all citizens, such as playgrounds for chil- dren, bowling courts and so forth. In addition to the project, other important points for successful operation are in ensuring active participation by allotment hol- ders, preparing regulations and organising a management body. Participation by allotment holders starts right from when the area is being created under the management and coordina- tion of specialised technicians, by helping to set out the allot- ments, build sheds and fences and plant hedges, etc. 16 1 - WHAT URBAN FORESTS ARE www.emonfur.eu

- 11. Their work continues by looking after their own sites and the common areas. The regulations should be clear and simple, defining the system for allocating allotments, the types of cultivation permitted, go- verning relations between allotment holders, and require that they preserve and improve on the high quality of the project. Picking a subject responsible for running the area means ensu- ring that there is active, constant and long-lasting management and control. The Centre of Urban Forestation also provides training courses, guided tours, competitions and other pleasant forms and occa- sions for allotment holders to get together, and for cooperation from other users of the Park. 17 1 - WHAT URBAN FORESTS ARE www.emonfur.eu BOX Click HERE to download the Italian version

- 12. CASE STUDY: ENGLAND’S COMMUNITY FORESTS 18 CLIVE DAVIES Background In 1989 two UK Government organisations, the Countrysi- de Commission and Forestry Commission, issued a con- cept document called ‘Forests for the Community’ (1990). The document set out a vision to create a network of Com- munity Forests in England starting with three pilot projects in Staffordshire (West Midlands), Gateshead (North East England) and East London. The ambition was to sub- stantially increase woodland cover within the project area through new large-scale tree planting programmes. At the heart of the concept was the utilisation of a land- scape-scale planning approach delivered through a part- nership led by local authorities with key support from lo- cal stakeholders. BOX

- 13. It was envisioned that each Community Forest would employ a small staff team to enable and facilitate delivery by, for example, community involvement, raising funds and securing landowner agreement. A large-scale transfer of land from private to public ownership was not envisaged; incentivisa- tion would be a key approach. By 1994 twelve Community Forest partnerships were established and were operating across sub-regional local authority boundaries. This cross bo- undary approach required inter-local-authority cooperation. A Planned Approach Central to the concept of the Community Forest was that of a ‘planned approach’ with a Community Forest Plan required to turn ideas into reality. Advice papers were issued by Countryside Commission (1990), which set out, for the newly appointed project teams and local partners, the main strate- gic features of Community Forests. Two further advice pa- pers on ‘Management Plans’ and ‘Landscape Design’ (Coun- tryside Commission 1992) supplemented ten initial advice pa- pers, issued in 1990. 19 Click HERE to watch the interwiew with Clive Davies on Emonfur’s Youtube Channel 1 - WHAT URBAN FORESTS ARE www.emonfur.eu

- 14. 20 Advice Paper 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 Topic Philosophy of zoning Process of plan preparation Economic factors affecting implementation Planning issues Nature conservation and habitat creation Involving local communities Designing community forests for the less able Design issues relating to safety and fear in parks and woodlands Community Forests and archaeology Monitoring and evaluation Management plans: source of published information (added 1992) Landscape Design in Community Forests (added 1992) Notes Underlying principles for identifying zones within a community forest according to land use characteristics. To ensure the Community Forest Plan is the basis for land use planning and analysis. Land valuation and net annual incomes especially linked to landowning sector. Land cost and availability and project management. Reference made to biological resources and capital. This is an early reference to what would later develop into the Green Infrastructure approach and Ecosystem Services. Changes in land management. Focuses on the theme of resolving different perspectives and the rights of local people to participate in the planning process. Design principles. Design principles. Respecting heritage and creatively using land management changes to secure greater public access to heritage features. How the performance of community forests would be measured. Focused on Woodland planting and management, recreation and leisure, landscape, nature conservation, education, regional economic development, farm diversification, statutory planning and other strategic plans (embedding of Community Forest policies within) Based on Management Plans, Countryside Commission, England, CCP206 (1986). Distillation of Forestry Commission Community Woodland design guidelines (HMSO 1991). 1 - WHAT URBAN FORESTS ARE www.emonfur.eu Strategic characteristics of Community Forests in England adapted from the Advice manual for the preparation of community forests plans (Countryside Commission 1990 ed. Clive Davies 2014)

- 15. Challenges arising from the Planned Approach Countryside Commission as a main national sponsor of Commu- nity Forests insisted that Community Forest Plans were drafted and approved before implementation could begin. This led to tension with local partners who were eager to get started with implementation. In practice some implementation did occur prior to Community Forest Plan approval and was presented as ‘pilot activity’. Community Forest Plan preparation took betwe- en 18 – 24 months. Local Authority Planning Officers found the process challenging, as whilst the Community Forest Plan was non-statutory it would clearly be a material consideration is future local planning and development control decisions. Furthermore Central Government insisted that once defined – Community Forest boundaries should feature on local statutory plans, a discussion that did not go unchallenged but was enacted. Implementation Community Forests were instigated at the end of a major rea- lignment of the economy (Davies 2014). The previous decade had seen a rapid decline is primary industries such as coal mi- ning and steel production and the advent of a consumer eco- nomy defined by retail expansion, service and financial industri- es. One result of this change was significant land dereliction especially in former coalfield communities. The availability of large-scale derelict land proved to be a major opportunity for Community Forests notably in areas such as Tyneside and South Yorkshire. Hundreds of hectares of land were conver- ted into new community woodlands usually with a biodiversity focus and access for local communities. One such example is the Watergate Forest Park in Gateshead on the site of the Wa- tergate Colliery, which now features a lake, woodlands and wildflower meadows. By 2000 the majority of derelict land available for restoration by community forests had significantly diminished in extent. 21 1 - WHAT URBAN FORESTS ARE www.emonfur.eu

- 16. Community Forest partners had restored some whilst other land had been reclaimed for the booming housing market or for new industrial estates meeting the needs of the service sector. Interest from national partners was also changing, the rise of regional structures following the arrival of the 1997 ‘New La- bour’ government and a sector shift from conservation towards sustainable development led to a substantial refocusing of Com- munity Forest projects. Most notable would be their role in in- troducing, from the USA the Green Infrastructure approach and then applying it to regional regeneration. Across the coun- try the results were variable but it led to new opportunities in some areas notably in North West England, where the Regio- nal Development Agency embraced the concept. Land supply was always the greatest challenge faced by Com- munity Forests consequently creation of new landscape featu- res such as woodland, meadows and lakes were normally dri- ven by land opportunity. Where opportunities and local com- munity wishes coincided, projects emerged with the intention that they would, as far as possible be sustainable. A key aspect of sustainable land management was considered to be the involvement of local people in long-term management. This commitment would be essential once project teams had with- drawn to develop other projects elsewhere. A variety of tools and features were used to engage the public and create a new sense of place. Sculptural artwork was a popular tool and was described as ‘an advance coloniser for landscape change to come’ (Great North Forest Plan nd). Self evidentially there was a tension between the ‘planned approach’ favoured by Countryside Commission and embedded in the Community Fo- rest Plans and the opportunity driven aspect of land-supply. In reality local Forest teams who were to prove essential in crea- ting new local woodland creation opportunities and managing local stakeholder expectations managed the space between the realities of land supply vs. a planned approach. The long-term Inevitably the Community Forest programme morphed and adapted to changing political and economic circumstances. Alt- hough discussed in the 1990s the original 12 Community Fo- rests were not given statutory designation. This made them vul- nerable to changing local and national interests. Furthermore regionalisation, which started in 1997 and was effectively di- sbanded in 2011 led to significant regional funding differences. Some of the original Community Forests disappeared or were absorbed into other projects or local authority service depart- ments, in almost all these cases momentum ended. Conversely new Community Forest projects emerged and joined a loose partnership details of which can be found on the Internet. 22 1 - WHAT URBAN FORESTS ARE www.emonfur.eu

- 17. Legacy and Lessons The original twelve Community Forests have left a considerable legacy of woodlands and other habitats even where the proj- ects no longer exist. Most notable are the large areas secu- red during the 1990s when land supply derived from former ex- tractive industries allowed large scale afforestation. 25 years later it is possible to see that the Community Forests have been instrumental in many ways: a) They pioneered the building of landscape scale partners- hips involving government, stakeholders and local com- munities b) They succeeded in increasing local woodland cover albe- it not to the extent originally envisioned c) They attracted many £Mn of investment in new projects d) They built up local capacity in Forest teams that for their duration provided high quality services to local people. There are lessons to be transferred to other areas: 1. If it is intention that the project/area is to be long-term (and for the purposes of creating new Community Fo- rests this is strongly desirable) a structure needs to be in place to accommodate this. Statutory designation of the area and embedding a project team within a recognised agency such as a local authority in beneficial. The team also needs to be given wide terms of reference and an ability to be entrepreneurial in their approach. The team also needs to include technical competences such as in landscape design, ecology and forestry. 2. Mechanisms are needed to achieve implementation and these need to be conceived before the project commen- ces. Without mechanisms implementation will not occur. 3. Community engagement is essential and this is also a ba- sis for raising funds and securing political commitment to the project. REFERENCES Countryside Commission and Forestry Commission (1989) CCP270, Fo- rests for the Community, Cheltenham: Countryside Commission Countryside Commission (1990) CCP271, Advice Manual for the prepa- ration of a Community Forest Plan, Cheltenham: Countryside Commis- sion Great North Forest Plan (n.d.), Gateshead. Roe, M., Taylor, K. New Cultural Landscapes, (2014) Chapter 3, Da- vies, C. Old Culture and Damaged Landscapes. Routledge, London. 23 BOX 1 - WHAT URBAN FORESTS ARE www.emonfur.eu

- 18. One of the earliest documented usages of the term “urban forestry” dates back to 1894 in the Annual Report of the Board of Park Commissioners in Cambridge, Massachusetts (Cook 1984). In this document, the author touches on some challenges still faced by trees in the urban environment. That year, the care of street trees in Cambridge was transfer- red from the “street department” to the Park Commissioners. Cook laments, Why this arrangement was made in the beginning, and why it was for so many years continued, is not apparent. But that the art of ur- ban forestry – an art requiring special knowledge, cultivated taste and a natural sympathy with plant life – should have been made an adjunct of the strictly mechanical business of road building, shows that the governing powers in the past have been largely indifferent DEFINING URBAN FORESTRY 24 W. ANDY KENNEY BOX

- 19. in the matter of shade tree cultivation.” ... systematic official effort is now needed, not only to preserve what we already have; but also to raise the standard of shade tree culture to the requirements of the more cultivated taste which now prevails in the art of urban forestry. So, with this use of the term 120 years ago a strong case is ma- de for a more sensitive approach to the management of urban trees, but no clear definition is provided. The first definition of the term urban forestry has been attribu- ted to Eric Jorgensen while he was at The Faculty of Forestry, University of Toronto (Jorgensen 1986). He stated, Urban forestry is a specialized branch of forestry and has as its objecti- ves the cultivation and management of trees for their present and poten- tial contribution to the physiological, sociological and economic well- being of urban society. These contributions include the over-all ameliora- ting effect of trees on their environment, as well as their recreational and general amenity value. As the practice of urban forestry advanced in the 1980s, it of- ten seemed necessary to preface any discussion with a defini- tion of the term, perhaps because at that time it seemed to be an oxymoron to laypeople. Consequently, over the past deca- des, definitions of urban forestry have proliferated. Konijnendijk, et al. (2006) argue that there are two general “streams” in the definition of urban forestry in Europe. The first they consider is a narrow definition that relates primarily to fo- restry in urban woodlands (in or near urban areas). The se- cond broader stream adds to these woodlands smaller groups of trees and individual trees. This broader perspective is captu- red in a definition provided by Ball et al. (1999) Urban forestry is a multidisciplinary activity that encompasses the de- sign, planning, establishment and management of trees, woodlands and associated flora and open space, which is usually physically linked to form a mosaic of vegetation in or near built-up areas. It serves a ran- ge of multi-purpose functions, but it is primarily for amenity and the pro- motion of human well-being. 25 1 - WHAT URBAN FORESTS ARE www.emonfur.eu An example of a portion of an urban forest. Management in this type of forest could be considered to be intensive where the basic unit of management is the indivi- dual tree and based on arboricultural principles. (Image from Google Earth)

- 20. This definition and many contemporary ones, build on that of Jorgensen by broadly describing some of the activities included in what Jorgensen simply called “forestry”. The definition provided by Ball is consistent with the prevailing ones most commonly used in Canada and the United States. It also appears that this broader definition is similar to the trend in many other parts of the world. C.Y. Jim of the University of Hong Kong is of the opinion that urban forestry in Asia is ge- nerally pertains to “1) trees and forests and woodlands embed- ded in the built environment whereas “forests in the city's edge lying beyond developed areas would not be regarded as ur- ban forest. They would be considered as periurban forest.” (personal communication June, 2014). Francisco Escobedo of the University of Florida is of the opi- nion that the general definition used in Canada and the US (and hence also in Asia) is also the trend in much of Latin Ame- rica (personal communication June, 2014) The same appears to be true for West Africa (Fuwape and Onyekwelu , 2011), South Africa (South African Department of Water Affairs and Forestry, undated) and New Zealand (Justin Morgenroth of the University of Canterbury, New Zealand personal communica- tion June 2014). Escobedo also noted the challenges in crea- ting a clear definition when one tries to provide a literal transla- tion from English to Spanish; a challenge also noted for parts of Europe by Konijnendijk, et al. (2006). So, while the various definitions of urban forestry around the world are legion, Ball’s definition appears to encapsulate the use of the term as it is most often intended. Perhaps, the final statement in Ball’s definition is changing so- mewhat with the advent of initiatives such as iTree which reco- gnize the breadth of ecological, social and economic benefits derived from urban forests. Certainly, the contribution to hu- man well-being is significant, but the role of urban forests in mi- tigating some of the negative environmental impacts of human 26 1 - WHAT URBAN FORESTS ARE www.emonfur.eu An example of a periurban forest. Management in such a forest tends to be extensi- ve in nature and based on silvicultural principles with the forest stand as the basic unit of management. (Image from Google Earth)

- 21. activities in the broader environment appears to be gaining mo- re attention. These benefits are now well documented and will not be repeated here. However, it is important to note that they tend to accrue to the community as a whole as well as to the broader environment and not just to the owner of the tree or trees. Because of the diversity of the social, environmental and economic benefits, and the interdependence of the compo- nents of the urban forest, many jurisdictions are now recogni- sing the importance of managing urban forests as ecosystems and not simply as collections of trees. Such an approach also demands that the concepts of urban forestry must extend beyond the confines of municipally owned street rights-of-way and parks and on to private property, a jurisdiction that often represents most of the urban forest ecosystem, and hence gene- rates most of the benefits. Perhaps the evolution of the discipline is now at a stage where a concise definition is less important than recognition of how it is practised “on the ground”. While the term urban forestry, as it is defined above, may be espoused in certain jurisdictions with an urban forestry department or with an individual or team of professionals referred to as urban foresters, the pro- grams and management approaches they deliver would often be better described as arboriculture where the management fo- cus is on the individual tree rather than the urban forest per se. At least this appears to be the case in some parts of North America as noted by this author in Canada and Escobedo (per- sonal communication June 2014) in parts of the US and Latin America. While arboriculture can be an important aspect of ur- ban forestry, the terms should not be seen as synonymous. REFERENCES Anonymous. I-Tree; Tools for assessing and managing community fo- rests. Accessed June 4, 2014. http://www.itreetools.org/ Ball, R., Bussey, S., Patch, D., Simson, A., West, S., 1999. United King- dom. In: Forrest, M., Konijnendijk, C.C., Randrup, T.B. (Eds.), COST Ac- tion E12: Research and development in urban forestry in Europe. Office for Official Publications of the European Communities, Brussels, pp. 325–340. Cook, G.R.,1894. Report of the General Superintendent of Parks. To the Board of Park Commissioners, City of Cambridge, Massachusetts, pp. 71–98. Fuwape, J.A. and Onyekwelu, J.C. 2011. Urban Forest Development in West Africa: Benefits and Challenges. Journal of Biodiversity and Ecolo- gical Sciences. 1(1): 77-93. Jorgensen, E., 1986. Urban forestry in the rearview mirror. Arboricultu- ral Journal 10: 177-190. Konijnendijk, C.C., Ricard, R.M., Kenney, A. and Randrup, T.B. 2006. Defining urban forestry – A comparative perspective of North America and Europe. Urban Forestry & Urban Greening 4: 93-103. South African Department of Water Affairs and Forestry, undated. Ur- ban greening strategy: A guideline for community forestry staff and di- scussion document for external stakeholders. Accessed June 2, 2014. http://www2.dwaf.gov.za/dwaf/cmsdocs/Elsa/Docs/Forests/urban%2 0greening%20strategy.pdf 27 BOX 1 - WHAT URBAN FORESTS ARE www.emonfur.eu

- 22. In September 2013, a project, supported by ISPRA (Italian agency for environmental protection and research), has star- ted by the Italian Academy of Forest Science. The aims of the project are: a)to standardize the data concerning UPF at national le- vel; b)to select the key indicators toward a first inventory of Ita- lian UPFs The first phase of the survey consisted of a detailed analysis of a sample of 30 cities in Italy. According to the survey, the information on UPFs in Italy is very dispersed and it is al- most impossible to find two cities providing the same, or at least a comparable, typology of urban spaces hosting trees TOWARDS A TYPOLOGY OF URBAN AND PERIURBAN FORESTS (UPF) IN ITALY 28 FABIO SALBITANO, CHIARA SERENELLI, GIOVANNI SANESI, PAOLO SEMENZATO BOX

- 23. and woodlands. Therefore, the architecture of the typological classification of UPF in Italy was initially based on the medium- large scale Regional Forest maps. The Forest maps have been cross checked with the Corine Land Cover maps. By using a case study approach the following 7 UPF types ha- ve been described: 1. Woodlands. Deciduous, coniferous or mixed forests with a high degree of naturalness according to their forest ecosy- stem character and a management style oriented to maximi- ze traditional forest products (landslide protection, timber, firewood, NWFPs). Coppices or high forest, they are either public and private owned, served by forest roads, sometimes fenced. 29 1 - WHAT URBAN FORESTS ARE www.emonfur.eu Rome view from FAO terrace Winter view of the urban and periurban forest in Turin included the riparian forest vegetation of Po river

- 24. 2. Transitional woodland-scrub in succession. Scrubby or herba- ceous vegetation with variable density of scattered trees that can represent either woodland degradation or forest regene- ration/recolonization. Very often, this type of vegetation re- sults from the abandonment of former agriculture and/or grazing activities. In a minor number of cases it results from a spontaneous re-colonization of neglected periurban areas and brownfields. This type is the expression of secondary suc- cession processes with a very high variability of stages and pat- terns. It is often located in peripheral areas of densely ur- banized zones, in marginal areas of rapidly developing infra- structures, in interstitial position, in periurban rural areas, at the edge of fields. 3. Woodlands in historical parks. Deciduous, coniferous or mi- xed high forest (prevailing) showing geometric to semi-natu- ral structures, according to the initial design and the mana- gement applied. They are oriented to maximize landscape architecture issues and recreational/cultural services. Rather common in Italian cities, they are quite often associated or merging to formal gardens (e.g. Florence, Rome). They are at most privately owned, but there are many examples of pu- blic owned historical parks. The main character is that the woodland is part of the park deriving from an overall de- sign. The woodlands are planned and managed together with the rest of the park. The species composition can reflect or not the character of natural surrounding vegetation. Any- way, generally the forest are mixed deciduous and conife- rous. Very often, in local inventories and town planning do- cuments, they are classified in the generic category of "ur- ban green". They are almost always enclosed spaces, even 30 1 - WHAT URBAN FORESTS ARE www.emonfur.eu Transitional woodland-scrubland in the wooded area of the urban park of San Bartolo, Pesaro

- 25. with masonry, monuments and/or ruins of high historical and aesthetic value and not necessarily open to the public. 4. Urban parks. Very often recent (after 1600 a.D.) designated parkland in urban contexts include wooded areas, or public areas where the tree cover is prevailing, although associated with the increased artificiality of the substrate. This type dif- fer substantially from types n. 1 &3 because of the functional aspects of facilities and equipment as well as for the initial design and the intensity, directions and styles of manage- ment. They are often characterized by a high vegetation di- versity with an important component of exotic species. 31 1 - WHAT URBAN FORESTS ARE www.emonfur.eu Woodland in historical park of Ostia Antica, Rome Woodland in historical park of Ostia Antica, Rome

- 26. 5. Tree-lined/Wooded Squares. They differ from the previous ty- pes because of the architectural and formal character: very often the soil is at least partially paved and the area is loca- ted in a hard (built) urban context. The size is generally smal- ler and the shape is regular geometric. The tree planting scheme can be rather variable but the individual/small group tree plantation scheme is decisively prevailing. Woo- ded Squares certainly cannot be considered proper "woo- dlands", but they have been included in the typological sur- vey for size, hedging, tree age, and socio-ecological func- tions. Tree species composition may be quite variable, even though less diverse than the previous category. 6. Riparian forest vegetation. The forest zone buffering the ri- vers and streams is considered a distinctive type of urban and periurban forests. In almost all Italian cities they are con- sidered a crucial type of vegetation also because of the po- tential they have in terms of ecological connections or becau- se of the management required to control floods and dike ef- fects. It differs from tree-lines or wooded strips because of its width (> 20 m wide). The species composition of riparian fo- rest vegetation under semi-undisturbed and/or natural condi- tions, consists of plants that either are emergent aquatic plants, or herbs, trees and shrubs that thrive in proximity to water. 7. Botanical gardens. Although ascribable to the type “woo- dlands in historical parks”, the Botanical Gardens are ge- nerally considered as a stand-alone type for a series of rea- sons. In fact, the Botanical gardens constitute biodiversity hotspots in urban contexts and play a fundamental role in scientific, educational and communicative terms. They are not considered "forests”, due to the high degree of artificiali- ty, but they are key-places for a range of services provided to the urban community. 32 Winter view of Santo Spirito square, Firenze 1 - WHAT URBAN FORESTS ARE www.emonfur.eu

- 27. 33 Riparian forest vegetation in the Urban Park “Parco Chico Mendez”, San Donnino, Firenze BOX 1 - WHAT URBAN FORESTS ARE www.emonfur.eu

- 28. URBAN – PERI-URBAN: AN AREA OF DIFFICULT DEFINITION The concept of “urban” belongs to the established linguistic tradition of any urban development planning (urban = built-up area), and its characters are generally and clearly recognizable. Peri-urban areas, or “peri-urban landscapes”, however, represent a relatively recent and highly dynamic form of expansion of cities, which takes on extremely diverse configurations in various national and regional contexts, but which is characterized, in the evolutio- 34 PROCEDURES FOR THE IDENTIFICATION OF URBAN FORESTS 1.2 ENRICO CALVO, ANDREI VERLIČ, URŠA VILHAR

- 29. nary process of a city, by the cancellation of the traditional bor- der that is clearly identifiable between a city and countryside (An- trop, 2004), and which, at the same time, severed the functional distinction between urban areas and rural areas. The process of urban expansion that interests large and medium- sized European cities can be effectively summarized with the con- cept of “metropolisation” (Camagni 1999, who, in the modern sense, interpreted the phenomenon of an expansion not only of a built structure, but its infrastructure, networks and functions to- gether as a whole, which creates a merger of agglomerates that leads to a new form of agglomeration called a metropolis) and “megalopolis” (Gottmann 1964 Turri 2000, who identified an ur- banized space in continuum). What should also be taken into consideration is the opinion of the CESE, the Economic, Social and Environmental Council, with the issue of “Peri-urban Agriculture” (2004), and the role of the citizens’ perceptions of rural areas in the vicinity (Fleury and Donadieu 1997). In conclusion, it would appear interesting to quote the following expression from the project Pays.Med.Urban “Periurban Land- scape” (2011) (www.paysmed.net/pays-urban/): “In accordance with the dimensions of the urban areas and the geomorphological and functional features of the surrounding areas, the periurban landscape might have a more markedly farming connotation and, consequently, be seen as a peri-agri- cultural landscape. Alternatively, it might have predominantly natural features and thus be described as a peri-natural land- scape. Finally, it might still have – especially in hilly or mountai- nous areas – a high proportion of woods/forests and so labeled as a peri-forest landscape”. IDENTIFICATION OF URBAN FORESTS The experiences of inventories of urban forests are quite scarce. Each forest inventory certainly has some reference points in the urban area of interest, but even the few elaborations that have be- en acquired do not seem to give significant results (Corona et al. 2012). 35 1 - WHAT URBAN FORESTS ARE www.emonfur.eu

- 30. However, some specific inventories have given more encouraging results, such as the French National Forest Inventory which defi- nes “forests under urban influence” as forests that are loca- ted within a buffer of 10 km from the administrative limits of ur- ban units, as defined by INSEE, that have a population of > 50,000 inhabitants (RU, 2006). For the urban unit of Paris the extension zone has been set at 50 km, given the population den- sity and transport network. According to “Guides des forets urbaines et périurbanines”, edi- ted for the forests of the Kingdom of Morocco (2010), urban fo- rests are forest areas that have been incorporated into an urban fabric; peri-urban forests are forest areas that are situated under the influence of an urban space that is less than 30 Km. For the city of Vienna urban forests are those that are located within a buffer of 15 km from the city and its suburbs (Casalegno, 2011) For the city of Ljubljana instead, the forest areas that are located within a buffer of 1 km from the public transportation network are classified as urban (Hladnik and Pirnat, 2011). Further difficulties are encountered with the definition of peri-ur- ban. In fact, at the European level there are no common definitions for the identification of peri-urban areas, and several projects ha- ve attempted to give a definition with subsequent cartographic representation. 36 1 - WHAT URBAN FORESTS ARE www.emonfur.eu

- 31. Within the PLUREL project (www.plurel.net) peri-urban areas are defined as “discontinuous built development containing set- tlements of each less than 20,000 population, with an average density of at least 40 persons per hectare (averaged over 1km cells)” (Loibl and Köstl, 2008). L’OCSE (2006) provided a concept of rurality. It classifies areas as Predominantly Urban (PU), Intermediate (IR) or Predomi- nantly Rural (PR) on the basis of population density (urban> 150 inhab. / km²). The OCSE approach had been adopted by the EU (Decision 2006/144 EC), which added two additional criteria to the popula- tion density: the percentage of a population living in rural com- munities (> 50%) and the size of a main urban center located within a region. The “Urban Morphological Zone (UMZ)” defines the urban fabric of an area based on the classifications of land cover, generally the Corine Land Cover. A UMZ has been defined as “A set of urban areas laying less than 200m apart” (Simon et al., 2010). On the basis of this approach a work project on a European scale has been developed for the vegetation cover in urban and subur- ban areas: (Urban and Peri-Urban Tree Cover in European Citi- es: Current Distribution and Future Vulnerability Under Clima- te Change Scenarios di Casalegno S., 2011) (http://www.eea.europa.eu/data-and-maps/figures/green-urba n-areas-within-urbanmorphological-zones-2000) The Moland project (http://moland.jrc.it) (Technical Report EUR 21480 EN (2004) identifies a peri-urban area as a buffer of an urban area (“artificial areas” of the Corine Land Cover), which is calculated as follows: width of buffer = 0.25 x √A The DIAP method, developed by DiAP of the Polytechnic Univer- sity of Milan (Barbera et alii, 2012), identifies a variable geome- tric zone according to the population size of municipalities: • 200 meters for municipalities with 2,000 to 15,000 inhabi- tants, • 300 meters for municipalities with over 15,000 inhabitants, • 100 meters for municipalities with less than 2,000 inhabitants. The AGAPU method by CRASL (Centro di Ricerca per l’Ambien- te e lo Sviluppo Sostenibile della Lombardia) of the Università Cattolica di Brescia (Pozzi, Pareglio, 2012), bases on the evalua- tion of six indicators: • Socio-demographic characteristics (population density, elderly dependency ratio, number of college graduates within the popu- lation > 24 years of age) • Income/Employment (per capita income, density of income, number of employed within the active population) • Service offerings (density of department stores, density of ho- tels and B&Bs, density of banks) 37 1 - WHAT URBAN FORESTS ARE www.emonfur.eu

- 32. • Lifestyles and living conditions (population density, population of urban areas, number of autos per population, density of in- frastructure) • Land use and naturalness (municipal agricultural land, natural- ness index, form of urban areas) • Agricultural activities (SAU average, main types of companies, average age of operators, number of employees in the agricultu- ral sector in the total number of the employed). With the calculation of these indicators and the use of spatial analysis, and the subsequent aggregation of the municipal land area, the classification of a territory in 4 classes can be obtained: urban, peri-urban, rural and mountain/natural. Within the EMONFUR Project, in accordance with the project’s Scientific Board, a modified version of the Moland model was de- cided to be used as a methodology for defining the inventories of urban and peri-urban forests. This model has been applied on a municipal basis with several modifications: • Reclassification of municipalities to “urban” if: Surban + Speri- urban >25% of the Stotal (INSOR, 1994 – “Types of rural areas in Italy” by Daniela Storti, Istituto Nazionale di Economia Agra- ria) • inclusion of municipalities in the “primary area” that are consi- dered isolated within the primary area itself according to IN- SOR. This inclusion is imposed by the fact that there are no si- gnificant “non-urban” areas in an “urban” surrounding; • exclusion of municipalities, outside the primary area, with a po- pulation of <10,000. This classification defines an “urban” area as being clearly di- stinct from one that is rural and is based on the administrative limits of municipalities, which better serves the purposes for an inventory and its management. Within such areas, with respect to the purpose of an inventory, it is no longer considered essential to distinguish an urban area from a peri-urban one. In fact, the first area is identified as an ur- banized area as classified so by the different cartographic tools used, while the peri-urban area is considered the remaining part of the municipal territory. 38 1 - WHAT URBAN FORESTS ARE www.emonfur.eu

- 33. CORINE popolated areas Periurban area buffer Preliminary study Urban and periurban area Map 1: basic overlay Map legend scale 1: 600000 Urban and periurban areas Provincial Borders 39 1 - WHAT URBAN FORESTS ARE www.emonfur.eu

- 34. 40 PROVINCES N. Kmq % of province territory N. Kmq % of province territory Total (N.) Total (Kmq) BERGAMO 124 941,10 34,23 120 1808,53 65,77 244 2749,63 BRESCIA 86 1629,18 34,07 120 3152,16 65,93 206 4781,34 COMO 85 496,70 38,81 75 783,14 61,19 160 1279,84 CREMONA 3 168,70 9,53 112 1602,25 90,47 115 1770,95 LECCO 54 318,15 39,23 36 493,36 60,77 90 811,86 LODI 24 307,80 39,30 37 475,32 60,70 61 783,12 MANTOVA 9 348,80 14,89 61 1993,83 85,11 70 2342,63 MILANO 121 1361,23 86,43 13 213,81 13,57 134 1575,04 MONZA B. 55 405,70 100 0 0 0 55 405,70 PAVIA 21 463,4 15,60 169 2507,80 84,40 190 2971,20 SONDRIO 2 35,80 1,12 76 3161,34 98,88 78 3197,14 VARESE 130 1089,90 90,69 11 111,84 9,31 141 1201,74 TOTAL 714 7566,81 31,70 830 16302,72 68,30 1544 23870,19 URBAN AREA RURAL AREA MUNICIPALITIES, URBAN AND RURAL AREAS IN LOMBARDY REGION 1 - WHAT URBAN FORESTS ARE www.emonfur.eu

- 35. According to the modified Moland model that has been applied to this inventory, there are 7,566.81 Km2 of territory in the Lom- bardy Region that have been defined as urban, accounting for 31.70% of the total, pertaining to 714 municipalities which repre- sents 46.24% of the total. As stated in the tables and map, the distribution is obviously not equal: 100% of the territory of the Monza Brianza Province is in- cluded, 90.69% of Varese and 86% of Milan, and 100%, 92.20% and 90.3% of the municipalities, respectively. The pre-Alpine provinces are located at an intermediate position: Como (38.81% of its territory and 53.13% of its municipalities), Bergamo (34.23% and 50.82%), and Brescia (34.07% and 41.75%). Among all the agricultural or mountainous provinces with per- centages of <15%, Lodi is an exception with 39% of its urban ter- ritory and 39.34% of its municipalities. 41 1 - WHAT URBAN FORESTS ARE www.emonfur.eu Click HERE to download the Italian version

- 36. STUDY CASE IN SLOVENIA At the global level there isn’t any legally binding document that could be covered specifically in urban and peri urban forest (Knuth, 2005). One of the proposed methodologies, which could be used with adequate spatial definition of forests, is the one discussed and used in the project Moland (Monitoring Land Use / Cover Dyna- mics) (EEA, 2008). The aim of Moland was to assess, monitor and model the past, present and future development of cities and regions in terms of sustainable development. This should be achieved by the crea- tion of a database of land use and transport networks of different cities and regions in Europe. From our point of view, the methodology could be useful for map- ping urban and peri urban areas: it would be comparable for dif- ferent countries and would consequently allow for joint frame- works in addressing the areas of urban and peri urban forests. Procedure Areas were excluded on the basis of layer of continuous built-up area - internal area (core area) - centers of cities and larger towns. Around them there is a belt of peri urban (suburban) work area. The latter by Moland methodology typically correlates with the CORINE layer 'artificial surfaces' (in the formula labeled 'A'). Belt around the inner area was calculated according to the formula 0.25 x √ A. 42 1 - WHAT URBAN FORESTS ARE www.emonfur.eu Urban area map with eliminated small buildings and roads (green) in Ljubljana. (M. Kobal, 2012)

- 37. 43 1 - WHAT URBAN FORESTS ARE www.emonfur.eu Urban and periurban forests within urban and periurban areas in 7 Slovenia Forest Service forest management regions that include the 7 most populated cities (more than 20.000 inhabitants) in Slovenia. (M. Kobal, R. Pisek, A. Verlič, 2014) Kranj Ljubljana Novo mesto Celje Velenje Maribor Koper Urban forest area (ha) 428 3749 386 392 379 1102 88 Areas of forest within urban and periurban areas in 7 Slovenia Forest Service forest management regions that include the 7 most populated cities (more than 20.000 in- habitants) in Slovenia. (M. Kobal, R. Pisek, A. Verlič, 2014)

- 38. REFERENCES AAVV, 2011 – Periurban Landscape. Landscape planning guidelines. Antrop M., 2004 – Landscape change and the urbanization process in Eu- rope. Landscape and Urban Planning Burel F., Baudry J, 1999 – Ecologie du paysage, concepts, methods et ap- plications. Edition TEC et DOC, pg 359 Camagni R., 1999 – La pianificazione sostenibile delle aree periurbane. Il Mulino, Bologna Consiglio d’Europa, 2000 – Convenzione Europea del Paesaggio. CESE, Comitato economico e sociale europeo, 2004 – parere sul tema “L’agricoltura periurbana”. NAT/204, Bruxelles Casalegno S. 2011. Urban and PeriUrban Tree Cover in European Cities: Current Distribution and Future Vulnerability Under Climate Change Sce- narios. In: Global warming impacts: case studies on the economy, human health, and on urban and natural environments. Editor: S. Casalegno, Fon- d a z i o n e B r u n o K e s s l e r . - http://www.intechopen.com/books/global-warming-impacts-case-studies -on-the-economy-human-health-and-on-urban-and-natural-environment s Fleury A. Donadieu P., 1997 - De l’agriculture periurbaine a l’agriculture urbaine, Le courrier del’environnment de l’INRNE, n.3 Gottmann J., 1964 – Magalopolis: the urbanized north-eastern seaboard of United States. The MIT Press, Cambridge GUA, 2006 - Green urban areas within urban morphological zones ( 2 0 0 0 ) , E u r o p e a n E n v i r o n m e n t a l A g e n c y . http://www.eea.europa.eu/data-and-maps/figures/green-urban-areas-wit hin-urbanmorphological-zones-2000 GUA, 2011 - Percentage of green urban areas in core cities, European Envi- r o n m e n t a l A g e n c y - U R L : http://www.eea.europa.eu/data-and-maps/figures/percentage-of-green-u rban-areas Hladnik D, Pirnat J., 2011 – Linking naturalness and amenity: the case of Ljubljana, Slovenia. Urban forestry § urban Greening, 10 JRC, 2004 - The MOLAND model for urban and regional growth forecast - A tool for the definition of sustainable development paths - Technical Re- port EUR 21480 EN (2004) OCSE, 2006 – The new rural paradigm: policies and governance. OECD Pubblications, Paris Periurbanisation in Europe – synthesis report - www.plurel.net Periurbanisation in Europe – synthesis report - www.plurel.net Perrone C., Zetti I. 2010, Il valore della terra. Teorie e applicazioni per il dimensionamento nella pianificazione territoriale, a cura di, Franco Ange- li, Milano. Pareglio S. ( a cura di), 2013 – Analisi e governo dell’agricoltura periurba- na. Rapporto finale di ricerca, Editoriale Fondazione Lombardia per l’Am- biente Storti D., 2000 - Tipologie di aree rurali in Italia, a cura di - Istituto Nazio- nale di Economia Agraria. Turri E. , 2000 – La Megalopoli Padana. Marsilio, Venezia Urban forestry—Linking naturalness and amenity: The case of Ljubljana, Slovenia - Urban Forestry & Urban Greening, Volume 10, Issue 2, 2011, Pages 105–112 Urban morphological zone – version F2v0 – Definition and procedural s t e p s ( S i m o n , F o n s , M i l e n g o – 2 0 1 0 - http://www.eea.europa.eu/data-and-maps/data/urban-morphological-zo nes-1990-umz1990-f2v0-1 Urban sprawl in Europe - The ignored challenge - EEA Report – No 10/ 2006. A joint publication of the European Environment Agency and the E u r o p e a n C o m m i s s i o n ' s J o i n t R e s e a r c h C e n t r e . - http://moland.jrc.ec.europa.eu/index.htm http://www.paysmed.net/pays-urban/ (2011) 44 1 - WHAT URBAN FORESTS ARE www.emonfur.eu

- 39. BOSCOINCITTÀ by Paola Pirelli Boscoincittà is a public park belonging to Milan City Council, covering an area of about 120 hectares, with woods, meadows, wa- terways, wetlands and about 100 carefully tended allotments given to the public. An orchard, water garden and insect sanctuary are the most recent additions. Visitors feel as if they are in a natural habitat even though it was purpose-built and it’s the result of care- ful planning. DESCRIPTION OF A REPRESENTATIVE UPF IN LOMBARDY REGION 1.2.1 45 PAOLA PIRELLI, ENRICO CALVO

- 40. The Boscoincittà project began in 1974 on public lands that the City Council had set aside for this initiative, and it has been run by “Italia Nostra Association” since the very beginnings. As a re- sult, the Association aims to weave this natural habitat into the urban scene, involving the city’s inhabitants. Boscoincittà is the first case of urban forestation in the history of Italy which has involved thousands of volunteers to create a ma- nage the park. The park is situated in the metropolitan area west of Milan; to- gether with the Parco delle Cave, Parco di Trenno and neighbou- ring agricultural areas, they cover a total of about 1.000 hectares, becoming part of the greater Parco Regionale Agricolo Sud Mila- no. Since the beginning, the park has enjoyed a continual wealth of ideas, as well as the development of new areas and new planning to meet the many demands of the local communities . Conside- ring the ever-changing social needs of the city, the key to manage the park has always been the direct participation of the citizens in all phases of its development. For instance, the citizens had a direct hand at the tree planting and the creation of urban allot- ments. Today it is still run by Italia Nostra with the Centre of Urban Fo- restation, whose task is to plan and develop the park, organize lei- sure-time activities, encourage public participation in the crea- tion and protection of green areas, as well as gather and coordina- te all the helps and resources. The park is now well-established and well-known. It is widely used, with a strong participation in the initiatives that the Asso- ciation organises to promote the culture of urban green areas. It has become customary to use voluntary involvement in urban fo- restation, when creating urban green areas with other bodies and associations. For the agroforestry management between 1995-2010, the Fore- stry Management Scheme was drawn up to develop urban foresta- tion and at present is in the process of being updated. The Fore- stry Management Scheme is a legal document that defines the middle to long term objectives and outlines the management gui- 46 1974: the farmhouse and the area 1 - WHAT URBAN FORESTS ARE www.emonfur.eu

- 41. delines. Thus the planning and recording of any intervention can be carried out for the duration of the Scheme and its deve- lopment can be checked. Boscoincittà’s Forestry Management Scheme includes the management of different kinds of green areas, the paths and waterway systems and a safety plan regar- ding the well-being of plants and trees. The Milan City Council has drawn up a nine year agreement with Italia Nostra (at present this is the fourth agreement). This en- tails a yearly contribution of €570,000 and Italia Nostra receives a further €200,000 from other sources. The park is run by approximately 10 permanent members of staff, plus other collaborators and professionals. Link “Centro Forestazione Urbana”: http://www.cfu.it 47 1 - WHAT URBAN FORESTS ARE www.emonfur.eu

- 42. FORESTA CARPANETA by Enrico Calvo Foresta Carpaneta is one of the 8 Great Lowland Forests, intend- ed and funded by the Lombardy Region in the early 2000s for the landscape and ecological requalification of the Lombard low- land and large valley bottoms. (www.agricoltura.regione.lombardia.it) All of these forests had been realized near large urban centers (Milan, Brescia, Sondrio, Bergamo and Mantova) and therefore also carry out an important role for the improvement of urban conditions and the quality of life of its citizens. Foresta Carpaneta (www.ersaf.lombardia.it) covers an area of 41 hectares within the regional agro-forestry company of Carpaneta in the municipality of Bigarello, located approximately 6 km from the municipality of Mantova, and was realized between 2003 and 2005 with a forest plantation, predominately Quercus peduncolata L., for about 32% of the trees, utilizing a planting scheme of 2.5 x 2 meters, planting a total of 15 different prove- nances of Quercus peduncolata L. from 5 northern Italian re- gions (Piemonte, Lombardy, Emilia Romagna, Veneto and Friuli-V.G.). Foresta Carpaneta is a biogenetic reserve, which reconstitutes a genetic heritage of Quercus peduncolata L., originally inserted in the oak-hornbeam lowlands which covered the Po Valley during the protohistoric era. The forest was then supplemented by a few areas of controlled use: an open space, Parco di Arlecchino, with a dissemination center for lowland forests and an open-air theater; two thematic areas, the Horti Virgilianii, dedicated to the representation of the vegetation of life and its expressive forms and the works of a writer originally from Mantova, Virgilio, and “Espace Bouffier”, dedicated to the representation of the book “L'homme qui plan- tait des arbres” by Jean Giono and to the symbolic value of trees and the people who have fought for the protection of trees and forests all over the world (Wangari Maathai; Plan for the Planet of UNEP; Associazione Gariwo). 48 1 - WHAT URBAN FORESTS ARE www.emonfur.eu

- 43. This forest is also home to two permanent monitoring sites: a per- manent Kopp area linked with that of Bosco Fontana, and an area of the Emonfur network for urban and lowland forests. The forest was planted on an arable land that was previously cul- tivated with poplar or crop. Therefore, it is very fertile. The development of the plants is therefore significant, to the point that in several of the 6 to 7-year-old areas the first thinning out operations for the most developed species (poplars, elms and alders) has initiated in order to avoid competition with the Quer- cus peduncolata L. which was the forest’s target species. Several control areas has been realized for measuring the thin- ning out interventions and monitoring its results over time. (http://www.emonfur.eu/pagina.php?sez=91&pag=554&label=E FUF+2013) The Forest has been FSC certified since 2007 and PEFC certified since 2009. It was also the subject of certification for carbon cre- dits with the company LifeGate during the period 2008-2013. Since its planning stages, the Forest has started several participa- tion processes with the territory, local and scientific authorities and associations. This collaboration led to the signing of the “Foresta Carpaneta Agreement” among sixteen subjects, for the implementation of programs of sustainable development and the promotion of the Forest and its territory. (http://www.emonfur.eu/pagina.php?sez=91&pag=554&label=E FUF+2013) 49 1 - WHAT URBAN FORESTS ARE www.emonfur.eu Click HERE to download the Italian version

- 44. FOREST WITHIN THE TIVOLI, ROZNIK AND ŠIŠENSKI HRIB LANDSCAPE PARK Location Rožnik is a protected remnant of natural mixed forest that lies within the Tivoli, Rožnik and Šišenski Hill Landscape Park (Fig. 1). DESCRIPTION OF A REPRESENTATIVE UPF IN SLOVENIA 1.2.2 50 ANDREI VERLIČ, URŠA VILHAR

- 45. History In 1984, the 459 hectares area was declared a natural landmark (Odlok 1984). Since 2010 most of the forest area has been pro- tected (Odlok 2010), due to its highly emphasized social and eco- logical forest functions. Rožnik was originally appointed as “Ru- stovec”, namely due to the red soil. Today's name originates in German word Rosenbach (Pach), the Rosenberg (Kočar, 1993). German place name Rosenpach appears at the beginning of the 15th century on the slopes of the Šišenski hrib (Charter of l. 1403, according to Kočar, 1993). Site composition More than 60% of urban forests within the City of Ljubljana are mixed natural forests and have continuously offered a close-to- nature forest ecosystem experience to the citizens (Hladnik & Pir- nat 2011). The Tivoli, Rožnik and Šišenski hrib landscape park is composed of diverse, hilly parts with deep tranches and is for- med of four pronounced peaks: Šišenski hrib (429 m) Cankarjev vrh (394 m) Tivolski vrh (387 m) Debeli hrib (374 m). Rožnik represents a rich source of springs and streams. At the foot it is covered with a rather thick humus layer which becomes 51 1 - WHAT URBAN FORESTS ARE www.emonfur.eu Urban forests of Rožnik Fig. 1. The Tivoli, Rožnik and Šišenski hrib landscape park, marked with the black ellipse

- 46. thinner at higher altitudes. There is an area often thick layer of sandy loam, and higher still penetrate funds clay shale and sand- stone. The soils are yellow or red color, which is due to bedrock. There is deep loam to clay loam soil. The outer layers are air per- meable and deeply rooted. Deeper, however, due to higher clay impurities, the soil is worse. The chemical properties are acidic, poor in nutrients such as phosphorus and calcium. The climate is temperate continental. Due to reduced windiness and increased temperature inversion, the atmospheric pollution is increasing, as well as the number of days with fog, which in Ljubljana in long-term average is 150 days per year (Forest management plan, 1997). On the whole area of Rožnik there are three forest communities: • Blechno-Fagetum (mixed forests dominated by beech, oak and chestnut, thriving mainly on northern and eastern slo- pes, where the soil is deeper and humid) • Vaccinio-Pinetum (acidophilic pine forest covers in particular sunny exposures, in the southern and western slopes) • Alnetum glutinosae (alder located on the marshy part of the valley on the north and northwest side) According to the share of the growing stock of the forest manage- ment unit, Ljubljana is dominated by the following tree species: Scots pine (Pinus sylvestris) (22%), Sessile and Pedunculate oak (Quercus petraea and Quercus robur) (15%), European beech (Fagus sylvatica) (21%), Norway spruce (Picea abies) (19%) and Sweet chestnut (Castanea sativa) (8%) (ZGS 2007). Recreational use and conflicts A study conducted in 2010 (Smrekar et al. 2011) estimated about 1,750,000 visits to this forest per year. Compared to natural forests, urban forests in Rožnik possess se- veral specific social or environmental characteristics: • deforestation due to infrastructure and urbanization (Tavčar 2010); • pollution of air, soil, surface waters and groundwater (Jaz- binšek Sršen, Jankovič et al. 2010); • higher frequency of visitors and their use of forest infrastruc- ture (e.g. recreational activities, transportation) (Tavčar 2010); • illegal waste dumps, quarries and sandpits (Tavčar 2010); • different species composition (e.g. lower biodiversity compa- red to natural forests and higher occurrence of invasive spe- cies) (Jurc 2010); • smaller importance of wood production and higher use of ex- ternalities (Tavčar 2010); • altered horizontal and vertical forest structure (e.g. intensive litter gathering in the past) (Jurc 2010); • different population dynamics of pests and diseases compa- red to natural forests (Jurc 2010). 52 1 - WHAT URBAN FORESTS ARE www.emonfur.eu

- 47. A Vision for the Future The City of Ljubljana has a green vision. Within this scope, the City has been given the title of ‘European Green Capital for 2016”. (http://ec.europa.eu/environment/europeangreencapital/winni ng-cities/2016-ljubljana/index.html) Concerning green and open spaces, the City’s detailed objectives for development are to: • arrange and preserve all five potential green wedges in the city, that link the city centre with the hinterland, and repre- sent key macro-spatial component sections of the urban spa- ce, as well as important city climate corridors; • link together individual arrangements, areas and networks of green spaces into an integrated system of green areas; • ensure good accessibility and even distribution of green areas that is equal for all residents; • establish and arrange waterside features as a special element of the system of green areas; 53 1 - WHAT URBAN FORESTS ARE www.emonfur.eu The Trim Trail Mostec, located on a sandy path in the Tivoli, Rožnik and Šišenski hrib landscape park (http://www.tekac.si/novice/8038/nova_trim_steza_mostec_in_trim_otoki_na_pst.html) Renewed green parkland in the Tivoli, Rožnik and Šišenski hrib landscape park with play path, arranged on the basis of forest pedagogics (http://www.ljubljana.si/si/mol/novice/89797,1/gallery.html)

- 48. • ensure adequate climate, residential and ecological quality in the urban environment; • re-establish green areas that have become blighted through past construction (http://ec.europa.eu/environment/europeangreencapital/wi nning-cities/2016-ljubljana/ljubljana-2016-application/inde x.html) This concerns also urban and periurban forests, mainly the areas protected as forests with special purpose (Odlok, 2010). Long- term strategy includes arangements that will facilitate the City’s management of private forest properties (purchase, private – pu- blic partnership …) and improve overall governance of urban and periurban forets. Increasing urbanisation of population, as well as the growing awarness of personal health and well-being, drive many citizens into the forests for a restorative experience. However, the forms of recreation sometimes are not suitable for current recreational infrastructure and/or acceptable for private forest owners. Therefore, monitoring recreation impacts and visitors’ preferen- ces can prevent extensive damage to a forest ecosystem on one hand and ensure quality and safe recreation for citisens on the other. Solving these kinds of conflicts should be one of the priori- ties of UPF managers. 54 1 - WHAT URBAN FORESTS ARE www.emonfur.eu Notice board of the landscape park Tivoli, Rožnik in Šišenski hrib

- 49. LOCATION The Chevin Forest Park is a periurban woodland area, located some 16km to the north-west of Leeds City Centre – National Grid Refe- rence SE220445 [see Figure 1]. The word ‘Chevin’ probably originates from the Celtic word ‘cefn’ meaning a ridge, and it forms part of the northern topographical boundary of the City of Leeds, a city of some three-quarters of a million people, and the principal city of the Leeds City Region, an area of 5000km² with a population of about 3.5 million people. It occupies a north-facing, steeply sloping ridge rising from 100m on the north-west fringe to a summit of 289m. THE CHEVIN FOREST PARK LEEDS – A CASE STUDY FROM THE UK 55 ALAN SIMSON Figure 1. Location 1.2.3

- 50. HISTORY OF THE CHEVIN FOREST The Chevin Park was originally part of the mediaeval Forest of Knaresborough, one of the many Royal Forests that existed at that time. Much of the site was owned by the Fawkes family of Farnley Hall, a local country house estate and the family associa- ted with Guy Fawkes and the Gunpowder Plot of 05th November 1605, an attempt to blow up the Houses of Parliament in Lon- don. At that time, the lower slopes of The Chevin were thickly wooded with broadleaved species, and it was a hunting reserve for the Fawkes family and their guests. The upper slopes were al- so wooded, but were more open and managed primarily as a parkland. The artist JMW Turner was a frequent visitor to the estate in the early 19th century, and several of his paintings of The Chevin still exist. After extensive felling for timber during the 1939-1945 World War, some 128ha of the estate was donated by the Fawkes family to the then Local Authority [Otley Urban District Council] as a memorial to all the local people who had been killed in the war. The site was subsequently heavily re-stocked with conifers to pro- vide an eventual income for the Local Authority, and the site won an award in 1961 for the quality of its timber. 1974 heralded a pe- riod of change in local government in the UK, and ownership of The Chevin passed to Leeds City Council. Between 1979 and 1988, Leeds City Council purchased a number of parcels of land adjacent to The Chevin, creating a Forest Park of some 210 ha, criss-crossed with footpaths and bridle paths, allowing free pu- blic access and a variety of uses, including car parking, picnic- king, walking with or without a dog, rock-climbing and horse ri- ding. A Management Plan was drawn up to ensure a seamless conversion from an area of commercial woodland into an area of amenity periurban wooded landscape. The Chevin enjoyed desi- gnation as a Local Nature Reserve in 1989 in recognition of its im- portance for biodiversity, and received a Forestry Commission ‘Centre of Excellence’ award in 1994. The current Management Plan was agreed in 2007, and is scheduled to run until 2016. Figure 2. Edge of previous commercial woodland 56 1 - WHAT URBAN FORESTS ARE www.emonfur.eu

- 51. SITE COMPOSITION The Chevin Forest Park is long and narrow, stretching across a rocky escarpment for just under 4km in an east-west direction, being 1km wide at its widest point. It is bisected by a busy road that runs north-south through The Park, and the A660, the main Leeds Road forms the northern boundary [see Figure 3]. Figure 3. Plan The soils are mainly mineral soils overlaying Millstone Grit, ten- ding to be acidic in nature with a shallow humus layer, particu- larly on the upper slopes, where there are also some areas of natu- rally impeded drainage. On the lower slopes, there are brown fo- rest soils which are well-drained and friable. From an agricultu- ral perspective, all of the Chevin Park falls within a category of land called a Less Favourable Area, which recognises the econo- mic problems of farming such difficult land. Prevailing winds are from the west, and the north-facing slope is also exposed to north-easterly winds. The Chevin is an important site because it has a number of features of significant heritage value – biodiver- sity, geology, archaeology, history and trees. It is very well used for recreation, attracting over half a million visits per year, and boasts a number of habitats of great experiential quality – woo- dland, scrubland, heathland, grassland, water features and rocky crags. WOODLAND Plantation Woodland Large-scale tree planting was first carried out on The Chevin in 1787, transforming a predominantly open moorland landscape into a predominantly wooded landscape by 1820. A significant woodland clearance took place in 1942 on the Danefield Estate side of the Chevin as part of the ‘War Effort’, but this was fol- lowed by a 30-year programme of re-afforestation which started in 1952 with Danefield Wood. This was followed in 1958 by Deer Park Wood, Shawfield and Memorial Plantation in 1960, Foxscar in 1962, Holbeck in 1963/4, Keeper’s Wood in 1965, Flint Wood in 1066/7, Cold Flatts in 1967/8, Quarry Wood in 1970, Caley Wood in 1974/5 and Clever Wood in 1980. The names of these plantations have some local historic significance, and in 2009, each plantation had its own individual sign to inform visitors of their names, size and the date they were planted. This planting 57 1 - WHAT URBAN FORESTS ARE www.emonfur.eu