Pemphigus groups of skin blistering disorders

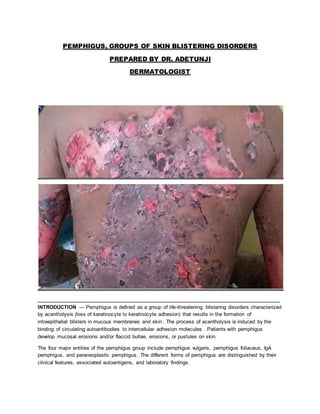

- 1. PEMPHIGUS, GROUPS OF SKIN BLISTERING DISORDERS PREPARED BY DR. ADETUNJI DERMATOLOGIST ____________________________________________________________________________________ INTRODUCTION — Pemphigus is defined as a group of life-threatening blistering disorders characterized by acantholysis (loss of keratinocyte to keratinocyte adhesion) that results in the formation of intraepithelial blisters in mucous membranes and skin . The process of acantholysis is induced by the binding of circulating autoantibodies to intercellular adhesion molecules . Patients with pemphigus develop mucosal erosions and/or flaccid bullae, erosions, or pustules on skin. The four major entities of the pemphigus group include pemphigus vulgaris, pemphigus foliaceus, IgA pemphigus, and paraneoplastic pemphigus. The different forms of pemphigus are distinguished by their clinical features, associated autoantigens, and laboratory findings.

- 2. The pathogenesis, clinical features, and diagnosis of pemphigus will be discussed here. The management of pemphigus and greater detail on paraneoplastic pemphigus could be otherwise treated separately, We shall later have a look into that. CLASSIFICATION — Common features of the major types of pemphigus are discoursed briefly below. A broader summary of the clinical and laboratory features of pemphigus is provided in the table below, pls critically observe them. ●Pemphigus vulgaris •Key features: Mucosal or mucosal and cutaneous involvement, suprabasal acantholytic blisters, autoantibodies against desmoglein 3 or both desmoglein 1 and desmoglein 3 •Clinical variants: Pemphigus vegetans, pemphigus herpetiformis ●Pemphigus foliaceus •Key features: Cutaneous involvement only, subcorneal acantholytic blisters, autoantibodies against desmoglein 1 •Clinical variants: Endemic pemphigus foliaceus (fogo selvagem), pemphigus erythematosus (Senear-Usher syndrome), pemphigus herpetiformis ●IgA pemphigus _{ Immunoglobulin A: secretion of a protain found in the blood serum} •Subtypes: Subcorneal pustular dermatosis-type IgA pemphigus (distinct from classic subcorneal pustular dermatosis [Sneddon-Wilkinson disease]), intraepidermal neutrophilic IgA dermatosis Key features: Grouped vesicles or pustules and erythematous plaques with crusts, subcorneal or intraepidermal acantholytic blisters, autoantibodies against desmocollin 1 in subcorneal pustular dermatosis-type IgA pemphigus . ●Paraneoplastic pemphigus •Key features: Extensive, intractable stomatitis and variable cutaneous findings; associated neoplastic disease; suprabasal acantholytic blisters; autoantibodies against desmoplakins or other desmosomal antigens . PATHOGENESIS Overview — Intensive investigations to elucidate the pathogenesis of pemphigus . have led to wide acceptance of the theory that acantholysis induced by the binding of autoantibodies to epithelial cell surface antigens leads to the clinical manifestations of pemphigus. This theory is supported by the consistent detection of intercellular autoantibodies in perilesional tissue from patients with pemphigus, Experimental findings that offer further support include the following: ●In vitro studies have demonstrated that autoantibodies from patients with pemphigus vulgaris, pemphigus foliaceus, and IgA pemphigus are capable of inducing destruction of epidermal cells. ●In vivo studies have shown that the passive transfer of IgG autoantibodies from patients with pemphigus vulgaris into neonatal mice induces blistering and erosions with histological, ultrastructural, and immunofluorescence features consistent with pemphigus . The blister-inducing potential of autoantibodies in pemphigus foliaceus and paraneoplastic pemphigus has been demonstrated in similar in vivo mouse studies.

- 3. ●Removal of pemphigus autoantibodies from serum from patients with pemphigus vulgaris or pemphigus foliaceus via antigen-specific immunoadsorption prior to injection into neonatal mice prevents blistering . The molecular mechanisms through which binding of autoantibodies to epithelial cells leads to acantholysis are still intensively debated. Several mechanisms for antibody-mediated acantholysis have been proposed, including the induction of signal transduction events that trigger cell separation and the inhibition of adhesive molecule function through steric hindrance. In particular, the theory of apoptolysis suggests that acantholysis results from autoantibody-mediated induction of cellular signals that trigger enzymatic cascades that lead to structural collapse of cells and cellular shrinkage . Target antigens — Autoantibodies against a variety of epithelial cell surface antigens have been identified in patients with pemphigus. Pemphigus vulgaris and pemphigus foliaceus — Desmogleins, which are transmembrane glycoproteins in the cadherin (calcium-dependent cell adhesion molecule) family, are the antigens that have been most extensively studied in pemphigus vulgaris and pemphigus foliaceus. Desmogleins are components of desmosomes, integral structures for cell-to-cell adhesion. IgG autoantibodies to desmogleins are consistently detected via enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) in patients with pemphigus, and the expression of these autoantibodies often correlates with the type of disease . Autoantibodies against desmoglein 1 have been linked to pemphigus foliaceus and autoantibodies to desmoglein 1 and desmoglein 3 have been linked to mucocutaneous pemphigus vulgaris. The amino-terminal portions of desmogleins appear to be the important epitopes for pathogenicity as evidenced by studies that demonstrate that IgG directed against an amino-terminal recombinant fraction of desmoglein 3 (EC1-2), but not the carboxy-terminal portion, induce epithelial blistering when injected into neonatal mice or exposed to cultured human skin . The autoantibodies considered to be pathogenic are of the IgG4 subclass . In the 1990s, the desmoglein compensation theory was proposed as an explanation for the observed correlation between the clinical features and autoantibody profiles of pemphigus vulgaris and pemphigus foliaceus . Although the theory is still widely cited, subsequent data has raised questions about whether this concept sufficiently explains the pathogenic mechanism of these diseases According to the desmoglein compensation theory, the correlation between clinical findings and ELISA results reflects innate differences in desmoglein expression in the skin and mucous membranes .In the skin, desmoglein 1 is expressed most intensely in the upper portions of the epidermis, whereas desmoglein 3 is more strongly expressed in the basal and parabasal layers. In the mucous membranes, desmoglein 3 is present in abundance throughout the epithelium. In contrast, the expression of desmoglein 1 is much lower throughout the mucosal epithelium . The interpretation of this theory as it relates to the clinical findings in pemphigus is as follows: ●Patients with only autoantibodies against desmoglein 3 should have mucosal dominant pemphigus vulgaris because in skin, desmoglein 1 compensates for the loss of desmoglein 3. In the mucous membranes, the expression of desmoglein 1 is insufficient for compensation. ●Patients with only autoantibodies against desmoglein 1 should have pemphigus foliaceus (superficial skin blistering and no mucous membrane involvement) because autoantibodies against desmoglein 1 result in separation of cells in the superficial epithelium, but not

- 4. in the deeper epithelium, where desmoglein 3 compensates well for desmoglein 1 dysfunction. The mucous membranes are spared due to the high levels of desmoglein 3 and the relatively low levels of desmoglein 1 expressed in mucosa. ●Patients with both autoantibodies against desmoglein 1 and 3 should have mucocutaneous pemphigus vulgaris because dysfunction of both desmoglein 1 and 3 prevents the ability of these glycoproteins to compensate for one another, resulting in a loss of cell-cell adhesion in both skin and mucous membranes. However, it is likely that the pathogenesis of pemphigus is more complex than this model predicts. Discordance between the clinical and serological profiles (eg, patients with pemphigus foliaceus who have autoantibodies against desmoglein 3, patients with pure mucosal pemphigus vulgaris who have autoantibodies against desmoglein 1, and patients with pemphigus who have neither autoantibodies against desmoglein 1 nor autoantibodies against desmoglein 3) may occur in about one-third of cases This observation and the knowledge that the presence of autoantibodies to both desmoglein 1 and desmoglein 3 does not result in complete dissolution of the epithelium suggest that other factors contribute to the development of these diseases. Autoantibodies against desmocollin 3 may contribute to pemphigus in some patients. Like desmogleins, desmocollins are transmembrane glycoproteins found within desmosomes . Desmocollin 3-specific autoantibodies from patients with pemphigus have induced loss of keratinocyte adhesion ex vivo and in experimental animals . Moreover, a subset of patients with clinical features most consistent with pemphigus herpetiformis or pemphigus vegetans and direct immunofluorescence findings consistent with pemphigus who have autoantibodies against desmocollin but no autoantibodies against desmoglein has been identified . Additional autoantibodies detected in serum from patients with pemphigus include autoantibodies against desmoglein 4, the acetylcholine receptor, pemphaxin, and others , Whether any of these autoantibodies are pathogenic in pemphigus vulgaris or pemphigus foliaceus remains to be determined. IgA pemphigus — Unlike the other forms of pemphigus, which are characterized by IgG autoantibodies targeting epithelial cell surface antigens, IgA pemphigus is characterized by anti-keratinocyte cell surface autoantibodies of the IgA class . The target antigen in the subcorneal pustular dermatosis type of IgA pemphigus is desmocollin 1, a transmembrane glycoprotein within desmosomes . In contrast, the targeted antigens in the intraepidermal neutrophilic dermatosis variant of IgA pemphigus appear to be more heterogeneous. While autoantibodies against desmogleins 1 and 3 have been reported in several patients , immunoelectron microscopy studies suggest that IgA autoantibodies in these patients recognize an unidentified non-desmosomal transmembranous protein. Thus, a common autoantigen remains elusive and the mechanism of blister formation in IgA pemphigus is not fully understood . Paraneoplastic pemphigus — Multiple autoantibodies have been detected in patients with paraneoplastic pemphigus. The target antigens for this variant are reviewed separately. Contributing factors — As with many other autoimmune diseases, the precipitating factors of pemphigus diseases are poorly understood. Both genetic and environmental factors may influence the development of pemphigus

- 5. Genetics — Multiple studies have evaluated the relationship between pemphigus vulgaris and pemphigus foliaceus with human leukocyte antigen (HLA) class II alleles. Pemphigus vulgaris is associated with DR4 and DR14, though the susceptibility gene differs dependent upon ethnic origin. HLA- DRB1 0402 is associated with the disease in Ashkenazi Jews and DRB1 1401/04 and DQB1 0503 are associated pemphigus vulgaris in non-Jewish patients of European or Asian descent . Sporadic and endemic pemphigus foliaceus are also associated with DR4, DR14, and DR1 alleles. In contrast to pemphigus vulgaris, the association with HLA alleles in pemphigus foliaceus is less restricted. DRB1 0402, 0403, 0404, 0406, 1401, 1402, 1406, and 0102 subtypes have been detected at increased frequency in patients with pemphigus foliaceus, while DRB1 0301, 0701, 0801, 1101, 1104, and 1402 are negatively associated with this disease . The involvement of genetic factors in susceptibility to pemphigus is further strengthened by detection of low titers of desmoglein 3-specific autoantibodies in asymptomatic relatives of patients with both pemphigus vulgaris and foliaceus. In addition, a case-control study found that compared with relatives of healthy controls, first-degree family members of patients with pemphigus had an increased prevalence of autoimmune diseases. Environment — While most cases of pemphigus foliaceus are idiopathic, environmental factors appear to contribute in the development of endemic pemphigus foliaceus (fogo selvagem) . A black fly (Simulium nigrimanum) or other insects may serve as a vector for the endemic form of this disease. Ultraviolet radiation has been proposed as an exacerbating factor for pemphigus foliaceus and pemphigus vulgaris . and pemphigus has been reported to develop following burns or cutaneous electrical injury . Viral infections, certain food compounds, ionizing radiation, and pesticides have been suggested as additional stimuli for this disease . Drug exposure — Pemphigus vulgaris and pemphigus foliaceus may be precipitated by drugs. Thiol drugs, including penicillamine and captopril, are the most common inciting agents. In one series of 104 patients treated with penicillamine for at least six months, 7 percent developed pemphigus foliaceus Examples of additional drugs that have been associated with pemphigus vulgaris or pemphigus foliaceus include penicillins, cephalosporins, enalapril,rifampin, and nonsteroidal antiinflammatory agents . Drug-induced biochemical and/or immunological reactions may contribute to the development of acantholysis in drug-induced pemphigus. Potential mechanisms include effects on enzymes that mediate keratinocyte aggregation, direct interference through binding to molecules involved in cell adhesion, and stimulation of neoantigen formation . Direct immunofluorescence (DIF) and indirect immunofluorescence (IIF) studies are negative in some patients with drug-induced pemphigus. In a series of six patients with this disorder, DIF was negative in one patient and IIF was negative in two patients .Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) was positive for desmoglein 1 or desmoglein 3 in all patients in this series. CLINICAL FEATURES Pemphigus vulgaris — Almost all patients with pemphigus vulgaris develop mucosal involvement. The oral cavity is the most common site of mucosal lesions and often represents the initial site of disease. Less frequently, mucous membranes in other sites are affected, such as the conjunctiva, nose, esophagus, vulva, vagina, cervix, and anus. In women with cervical involvement, the histological findings of pemphigus vulgaris may be mistaken for cervical dysplasia in Papanicolaou (Pap) smears.

- 6. Since mucosal blisters erode quickly, erosions are often the only clinical findings . The buccal mucosa and palatine mucosa are the most common sites for lesion development in the oral cavity. The pain associated with mucosal involvement of pemphigus vulgaris can be severe. Oral pain is often augmented by chewing and swallowing, which may result in poor alimentation, weight loss, and malnutrition. Most patients also develop cutaneous involvement manifesting as flaccid blisters on normal-appearing or erythematous skin. The blisters rupture easily, resulting in painful erosions that bleed easily .Pruritus usually is absent. Although any cutaneous site may be affected, the palms and soles are usually spared. The Nikolsky sign (induction of blistering via mechanical pressure at the edge of a blister or on normal skin) often can be elicited . Rarely mucous membrane involvement is not observed despite the presence of circulating autoantibodies to both desmoglein 1 and desmoglein 3 .The term “cutaneous-type pemphigus vulgaris” is used to refer to this presentation of the disease. Other uncommon clinical presentations of pemphigus vulgaris include: ●Pemphigus vegetans – Patients with pemphigus vegetans present with vegetating plaques composed of excessive granulation tissue and crusting . The intertriginous areas, scalp, and face are the most common sites for these lesions. Two clinical presentations of pemphigus vegetans have been described . In pemphigus vegetans of Neumann, vegetating plaques evolve from typical pemphigus vulgaris lesions. Pemphigus vegetans of Hallopeau is a milder form of pemphigus vegetans in which the vegetating plaques are not preceded by bullae. Lesions of pemphigus vegetans of Hallopeau usually are found in intertriginous areas. ●Pemphigus herpetiformis – Pemphigus herpetiformis (also known as herpetiform pemphigus) is a term that describes pemphigus vulgaris or pemphigus foliaceus that manifests with urticarial plaques and cutaneous vesicles arranged in a herpetiform or annular pattern .Pruritus is frequently present. Mucosal involvement is uncommon. The clinical features of drug-induced pemphigus vulgaris are similar to idiopathic disease. Pemphigus foliaceus — Pemphigus foliaceus is a superficial variant of pemphigus that presents with cutaneous lesions. The mucous membranes are typically spared . Pemphigus foliaceus usually develops in a seborrheic distribution. The scalp, face, and trunk are common sites of involvement. The skin lesions usually consist of small, scattered superficial blisters that rapidly evolve into scaly, crusted erosions .The Nikolsky sign often is present . The skin lesions may remain localized or may coalesce to cover large areas of skin. Occasionally, pemphigus foliaceus progresses to involve the entire skin surface as an exfoliative erythroderma . Pain or burning sensations frequently accompany the cutaneous lesions. Systemic symptoms are usually absent. Clinical variants of pemphigus foliaceus include: ●Endemic pemphigus foliaceus (fogo selvagem): Endemic pemphigus foliaceus presents with clinical features that are similar to the idiopathic form of the disease . An environmental trigger is believed to account for this variant of the disease . ●Pemphigus erythematosus (Senear-Usher syndrome): This term pemphigus erythematosus is used to describe pemphigus foliaceus localized to the malar region of the face .Historically, the term

- 7. was used to refer to patients who exhibited immunofluorescence findings consistent with pemphigus as well as laboratory features of systemic lupus erythematosus. However, the term is no longer used in this manner. The clinical manifestations of drug-induced pemphigus foliaceus are similar to idiopathic disease. IgA pemphigus — Both the subcorneal pustular dermatosis and intraepidermal neutrophilic IgA dermatosis types of IgA pemphigus are characterized by the subacute development of vesicles that evolve into pustules . The vesicles and pustules are usually, but not always, accompanied by erythematous plaques. A herpetiform, annular, or circinate pattern may be present . The trunk and proximal extremities are common sites for involvement. The scalp, postauricular skin, and intertriginous areas are less common sites for lesion development . Pruritus may or may not be present. Mucous membranes are usually spared. The subcorneal pustular dermatosis type of IgA pemphigus is clinically similar to classic subcorneal pustular dermatosis (Sneddon-Wilkinson disease). Immunofluorescence studies are necessary to distinguish these diseases. Paraneoplastic pemphigus — Paraneoplastic pemphigus (also known as paraneoplastic autoimmune multiorgan syndrome) is an autoimmune multi-organ syndrome associated with neoplastic disease .Typically, patients suffer from severe and acute mucosal involvement with extensive, intractable stomatitis . The cutaneous manifestations are variable, and include blisters, erosions, and lichenoid lesions that may resemble other autoimmune blistering diseases, erythema multiforme, graft versus host disease, or lichen planus . Life-threatening pulmonary involvement consistent with bronchiolitis obliterans also may be seen . Neonatal pemphigus — Neonatal pemphigus is a rare transient condition in which neonates develop blisters due to placental transmission of autoantibodies from a mother with pemphigus. Neonatal pemphigus vulgaris occurs more frequently than neonatal pemphigus foliaceus . The clinical, histological, and direct immunofluorescence findings of neonatal pemphigus are consistent with pemphigus. Indirect immunofluorescence has been positive in the majority of reported cases . The disease manifestations usually resolve within three weeks. DIAGNOSIS — The diagnosis of pemphigus is made through the assessment of clinical, histological, immunopathological, and serological findings . Even in cases in which the clinical findings strongly suggest pemphigus, laboratory investigations to confirm the diagnosis are indicated since other disorders may present with similar clinical findings . Pemphigus vulgaris and pemphigus foliaceus — In addition to a complete examination of cutaneous and mucosal surfaces, the clinical assessment should include a review of the patient’s medic ations since clinical and laboratory studies cannot reliably distinguish between idiopathic pemphigus and drug-induced pemphigus. In addition, patients who may have pemphigus vulgaris should be questioned about ocular symptoms, hoarseness, dysphagia, dysuria, and dyspareunia to evaluate for symptoms suggestive of extraoral mucus membrane involvement . Our standard laboratory work-up for patients with clinical findings suggestive of pemphigus foliaceus includes: ●A lesional skin or mucosal biopsy for routine hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining

- 8. ●A perilesional skin or mucosal biopsy for direct immunofluorescence (DIF) ●Serum collection for enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) and indirect immunofluorescence (IIF) Histopathology — The biopsy for routine histological examination should be taken from an early lesion. The biopsy should be placed at the edge of a blister or erosion. A 4 mm punch biopsy is usually sufficient. The characteristic findings in pemphigus vulgaris include: ●Intraepithelial cleavage with acantholysis (detached keratinocytes) primarily localized to the suprabasal region ●Retention of basal keratinocytes along the basement membrane zone, resulting in an appearance that resembles a “row of tombstones” ●Sparse inflammatory infiltrate in the dermis with eosinophils In the pemphigus vegetans variant of pemphigus vulgaris, the suprabasal cleavage is accompanied by hyperkeratosis, papillomatosis, and prominent acanthosis with downward proliferation of the rete ridges [97]. Eosinophils may be present within the areas of cleavage. The characteristic findings of pemphigus foliaceus include “ ●Intraepithelial cleavage with acantholysis beneath the stratum corneum or within the granular layer; neutrophils within the blister cavity are occasionally seen ●Mixed inflammatory infiltrate in the superficial dermis with eosinophils and neutrophils; eosinophils may be more prevalent in drug-induced pemphigus foliaceus Direct immunofluorescence — Unlike the biopsy for routine histological examination, the biopsy for DIF should be taken from normal-appearing perilesional skin or mucosa. The biopsy should not be placed in formalin. Both pemphigus vulgaris and pemphigus foliaceus demonstrate intercellular deposition of IgG on DIF . Although some cases of pemphigus foliaceus demonstrate deposition of IgG that is primarily distributed in upper levels of the epidermis . DIF cannot be used to reliably distinguish between these diseases. Essentially all patients with idiopathic pemphigus vulgaris or pemphigus foliaceus have positive DIF results. Thus, if DIF is negative, the diagnosis should be questioned. In contrast, negative DIF studies may occur in patients with drug-induced pemphigus . Occasionally, intercellular deposition of antibodies occurs in other diseases (eg, spongiotic dermatitis, burns, toxic epidermal necrolysis, systemic lupus erythematosus, or lichen planus) . Serology — IIF and ELISA are serological studies that can detect circulating autoantibodies that bind epithelial cell surface antigens. In patients with positive DIF results, these tests are used to further support the diagnosis of pemphigus. Indirect immunofluorescence — More than 80 percent of patients with pemphigus vulgaris or pemphigus foliaceus have circulating antibodies detectable by IIF. The substrate used influences the test sensitivity [90]. Monkey esophagus is the preferred substrate for the diagnosis of pemphigus vulgaris. In contrast, normal human skin and guinea pig esophagus are the most sensitive substrates for the diagnosis of pemphigus foliaceus. In both disorders, IgG deposits are found intracellularly . IIF cannot be used to distinguish between these diseases.

- 9. Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay — ELISA for IgG antibodies to desmoglein 1 and desmoglein 3 is commercially available. ELISA is more sensitive and specific than IIF for the diagnosis of pemphigus vulgaris and pemphigus foliaceus . The sensitivity of ELISA exceeds 90 percent In addition, since desmoglein antibody levels often fall in the setting of clinical improvement, ELISA may aid with monitoring disease activity and the response to treatment . In a retrospective study that assessed the predictive values of pemphigus autoantibodies in patients with pemphigus vulgaris and pemphigus foliaceus, desmoglein 1 autoantibodies were more closely correlated with the disease course than desmoglein 3 autoantibodies. Desmoglein 3 antibody levels remained high during disease remissions in some patients with mucosal pemphigus vulgaris. In patients with pemphigus vulgaris, levels of IgE antibodies to desmoglein 3 may also correlate with disease activity . Other — Additional serological tests that may be used for the diagnosis of pemphigus vulgaris and pemphigus foliaceus include immunoblotting and immunoprecipitation. However, these tests are more difficult to perform than IIF and ELISA. Thus, they are infrequently used in the clinical setting. Aside from the detection of pemphigus antibodies in serum, pemphigus is not associated with specific laboratory abnormalities. Other laboratory abnormalities may occur related to complications of the disease or its treatment. IgA pemphigus — Similar to other forms of pemphigus, the diagnosis of IgA pemphigus is based upon the combined assessment of clinical and laboratory findings. The standard laboratory workup consists of histological examination, DIF, and IIF. Typical histological findings of IgA pemphigus include . ●Intraepidermal clefts and pustules located in a subcorneal location (subcorneal pustular dermatosis-type IgA pemphigus) or in the entire or mid-epidermis (intraepithelial neutrophilic dermatosis) ●Slight or absent acantholysis ●Mixed inflammatory infiltrate in the dermis DIF microscopy of perilesional skin reveals intercellular IgA deposition within the epidermis that is occasionally more pronounced in the upper epidermis. Weaker intercellular deposits of IgG and/or C3 may also be present .IIF on monkey esophagus demonstrating intercellular deposits of IgA offers further support for the diagnosis. However, IIF is positive in only 50 percent of patients . Other studies that have been utilized to identify circulating IgA pemphigus desmocollin autoantibodies include immunoblotting , ELISA using recombinant desmocollin , and immunofluorescence molecular assay using desmocollin-transfected COS-7 cells .The availability of these studies is limited to specialized centers and research settings. Although autoantibodies against desmocollin 1 appear to be strongly associated with the subcorneal pustular dermatosis type of IgA pemphigus, autoantibodies to desmogleins may be present in other patients with IgA pemphigus. In one series of 22 patients with IgA pemphigus, ELISA tests for IgA autoantibodies against desmoglein 1 or desmoglein 3 were positive in three patients and one patient, respectively .The patients with desmoglein autoantibodies had either the intraepidermal neutrophilic type of IgA pemphigus or a presentation that had clinical and pathological features of pemphigus foliaceus. None of the 10 patients with subcorneal pustular dermatosis-type IgA pemphigus had autoantibodies

- 10. against these desmogleins, but all 10 had serum samples that reacted with desmocollin 1 expressing COS-7 cells. Paraneoplastic pemphigus — Similar to other forms of pemphigus, the diagnosis of paraneoplastic pemphigus involves review of clinical, histological, immunopathological, and serological findings. The diagnosis of paraneoplastic pemphigus vulgaris is reviewed separately. DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS — Multiple mucocutaneous blistering diseases share clinical features with the different forms of pemphigus. In all forms of pemphigus, laboratory investigations, particularly immunopathological tests, usually easily distinguish pemphigus from other diseases. ●Pemphigus vulgaris – Cutaneous involvement in pemphigus vulgaris must be distinguished from other autoimmune blistering diseases. The morphology of cutaneous blisters in pemphigus vulgaris can be helpful for narrowing the differential diagnosis. The flaccid blisters often seen in pemphigus vulgaris contrast with the tense blisters that are frequently seen in association with subepithelial blistering diseases . Mucosal lesions pemphigus vulgaris can resemble other blistering or erosive disorders of the mucous membranes. As examples, the possibility of other pemphigus variants, mucous membrane pemphigoid, mucosal linear IgA bullous dermatosis or epidermolysis bullosa acquisita, erythema multiforme, and Stevens-Johnson syndrome should be considered. ●Pemphigus foliaceus – The lesions of pemphigus foliaceus may resemble other inflammatory disorders, such as seborrheic dermatitis . impetigo, subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus ,IgA pemphigus, and the non-IgA pemphigus form of subcorneal pustular dermatosis ●IgA pemphigus – The differential diagnosis of IgA pemphigus overlaps with pemphigus foliaceus. In addition, disorders that may present with grouped vesicular lesions or pustules, such as dermatitis herpetiformis , bullous impetigo, linear IgA bullous dermatosis and pustular psoriasis should be considered. ●Paraneoplastic pemphigus – The differential diagnosis of paraneoplastic pemphigus is reviewed separately. SUMMARY AND RECOMMENDATIONS ●Pemphigus comprises a group of autoimmune blistering diseases that are characterized by histological acantholysis (loss of cell-to-cell adhesion) and mucosal and/or cutaneous blistering. The four major types of pemphigus are pemphigus vulgaris, pemphigus foliaceus, IgA pemphigus, and paraneoplastic pemphigus . ●Pemphigus is rare. Pemphigus vulgaris is the most common form of pemphigus. However, in certain areas, particularly in locations where an endemic form of pemphigus foliaceus occurs, pemphigus foliaceus is more prevalent. ●The intraepidermal blistering observed in pemphigus occurs due to an immune response that results in the deposition of autoantibodies against epidermal cell surface antigens within the epithelium of mucous membranes or skin. The mechanism through which acantholysis occurs is not fully understood.

- 11. ●The desmoglein compensation theory has been proposed as an explanation for the frequently observed correlation of the clinical presentation of pemphigus vulgaris and pemphigus foliaceus with specific circulating autoantibodies . Circulating autoantibodies to desmoglein 1 are associated with cutaneous involvement, whereas circulating autoantibodies against desmoglein 3 have been linked to mucosal disease. Since desmogleins are not the only molecules that contribute to cell adhesion and not all patients exhibit antibody profiles consistent with this theory, it is likely that autoantibodies against other epithelial antigens are involved in these diseases. ●Pemphigus vulgaris generally is a more severe disease than pemphigus foliaceus. Patients with pemphigus vulgaris usually present with widespread mucocutaneous blisters and erosions Cutaneous blistering in pemphigus foliaceus tends to occur in a seborrheic distribution .Compared with pemphigus vulgaris, blistering in pemphigus foliaceus is more superficia ●Vesicles, pustules, and crusts on skin are common features of IgA pemphigus. The skin lesions may appear in an annular, circinate, or herpetiform distribution. ●The diagnosis of pemphigus is based upon the recognition of consistent clinical, histological, and direct immunofluorescence findings, as well as the detection of circulating autoantibodies against cell surface antigens in serum. Laboratory studies are useful for distinguishing pemphigus from other blistering and erosive diseases. Systemic glucocorticoids are the mainstay of therapy for pemphigus vulgaris and pemphigus foliaceus, and are usually highly effective for obtaining control of disease. Nonsteroidal immunomodulatory agents such as azathioprine, mycophenolate mofetil, and dapsone commonly are prescribed in conjunction with systemic glucocorticoids in an attempt to minimize the risk for adverse effects of long-term, high-dose glucocorticoid therapy. Other interventions, including rituximab, intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG), and cyclophosphamide are typically reserved for patients who fail to respond to these conventional therapies. The initial management of pemphigus vulgaris and pemphigus foliaceus will be reviewed here. The management of refractory pemphigus vulgaris and pemphigus foliaceus, the pathogenesis and diagnosis of pemphigus, and the diagnosis and management of paraneoplastic pemphigus are reviewed separately. INDICATIONS FOR THERAPY — Although pemphigus vulgaris typically presents as a more severe disorder than pemphigus foliaceus due to the common presence of both mucosal and cutaneous involvement .both disorders can lead to significant morbidity. Oral mucosal involvement, which occurs in almost all patients with pemphigus vulgaris, usually is accompanied by severe pain, and may lead to poor alimentation resulting in weight loss and malnutrition .In addition, the widespread loss of the epidermal barrier that occurs in pemphigus vulgaris and pemphigus foliaceus may lead to protein loss, fluid loss, electrolyte imbalances, dietary insufficiencies, increased catabolism, and increased risk for local and systemic infections . The complications of pemphigus vulgaris can be life-threatening; it is estimated that prior to the use of systemic immunosuppressants, more than 70 percent to nearly 100 percent of patients died within one to five years .Pemphigus foliaceus, which is characterized by shallow blisters and involvement limited to the skin, is considered to have a better prognosis than pemphigus vulgaris .however, progression of pemphigus foliaceus may lead to extensive involvement and similar complications.

- 12. Given the potential for severe morbidity and mortality from pemphigus vulgaris and pemphigus foliaceus, treatment is always indicated at the time of disease onset, even for patients who initially present with only mild disease. However, treatment must be approached carefully because the therapeutic regimens utilized for pemphigus are not benign; most of the currently estimated 5 to 10 percent mortality rate from pemphigus vulgaris is considered to result from complications from treatment .Infections ranging from minor skin infections to life-threatening opportunistic infections are common complications of the immunosuppressive regimens typically used for pemphigus therapy . APPROACH TO TREATMENT — The goal of treatment in pemphigus is to induce complete remission while minimizing treatment-related adverse effects. The paucity of large, high-quality prospective trials that compare the therapeutic options for this disease as well as the variability in study protocols, outcome measures, and results have made definitive conclusions on the best approach to treatment difficult The approach to treatment of pemphigus vulgaris and pemphigus foliaceus is similar. Many studies that have evaluated therapies for pemphigus have combined patients with these disorders . The first priority for patient management is to attain rapid disease control. This is typically achieved through the administration of systemic glucocorticoids. The response to systemic glucocorticoid therapy often is fast; clinically significant improvement is usually evident within two weeks. Although systemic glucocorticoid therapy is highly effective, the high doses and long treatment periods that are needed to maintain the clinical response may lead to serious or life-threatening side effects [4]. For this reason, a nonsteroidal systemic immunomodulatory medication is often used as an adjunct to systemic glucocorticoid therapy in an attempt to minimize glucocorticoid consumption. However, the value of adjuvant therapy for improving patient outcomes remains uncertain. Azathioprine, mycophenolate mofetil, and cyclophosphamide are the most common drugs utilized in combination with glucocorticoids for patients with pemphigus. Many clinicians consider azathioprine the immunosuppressant drug of choice due to the relatively long history of use of this drug for this indication and a randomized trial that supported a glucocorticoid-sparing effect superior to mycophenolate mofetil Cyclophosphamide is typically reserved for severe and refractory cases due to its less favorable side effect profile. The approach to the initiation of nonsteroidal adjuvant agents varies. Some clinicians routinely prescribe a nonsteroidal agent at the start of treatment with a systemic glucocorticoid or shortly after the start of glucocorticoid therapy. Other clinicians primarily begin use of these agents when disease flares occur during glucocorticoid tapering or when the response to systemic glucocorticoid monotherapy remains unsatisfactory after several weeks. Definitive conclusions on the best approach are complicated by limited and conflicting data on the glucocorticoid-sparing effects and prognostic impact of these agents. FIRST-LINE THERAPY — Systemic glucocorticoids play a central role in the treatment of pemphigus due the high efficacy of these agents for achieving rapid control of the disease [18]. Systemic glucocorticoids Efficacy — Support for the use of systemic glucocorticoids as the primary treatment for pemphigus stems from randomized trials and other studies that have documented improvement in pemphigus with glucocorticoid monotherapy in the majority of patients, and extensive clinical experience with this treatment .As an example, in a randomized open-label trial in which 30 patients with pemphigus vulgaris were treated with prednisolone alone (2mg/kg per day), 23 of these patients (77 percent) responded to

- 13. treatment and the average time to cessation of blistering was 18 days The dramatic fall in mortality from pemphigus observed after the introduction of systemic glucocorticoid therapy also supports the value of systemic glucocorticoid therapy for this indication. Administration — Despite the well-accepted status of systemic glucocorticoids as the primary treatment for pemphigus, the optimum treatment regimen is not established. Oral therapy with prednisone, prednisolone, or methylprednisolone is the most common mode of glucocorticoid administration for patients with pemphigus. Multiple regimens have been utilized for glucocorticoid therapy. The most common approach consists of treatment with around 1 to 1.5 mg/kg per day ofprednisone or prednisolone . Alternatively, higher doses of prednisone or prednisolone (1.5 to 2.5 mg/kg per day) have been given as initial treatment. Direct comparisons of the efficacy and safety of these approaches are limited to a small randomized trial (n = 22) that compared high doses of prednisone(120 to 150 mg/kg per day) with lower doses of prednisone (45 to 60 mg/kg per day) in patients with newly diagnosed pemphigus vulgaris (n = 19) or pemphigus foliaceus (n = 3) .A statistically significant difference in the time to achieve initial disease control was not detected between patients treated with the higher and lower doses; the mean times to initial disease control were 20 (range 5 to 42 days) and 24 days (range 7 to 42 days), respectively. A significant difference in the rate of adverse effects also was not detected. Given the lack of evidence that treatment with higher doses or prednisone leads to better patient outcomes, most clinicians, including ourselves, initiate therapy with doses ranging from 1 to 1.5 mg/kg per day. If the clinical response is insufficient, we consider a rapid increase in dose up to a maximum of 2mg/kg per day. In most patients treated with systemic glucocorticoid therapy, cessation of blistering takes place within two to three weeks and full disease control is achieved within six to eight weeks . Once the disease activity is under control, glucocorticoid tapering should begin, with the goal of reaching the lowest dose needed to keep the disease under control. The ultimate goal is to withdraw all treatment. The optimal method of tapering glucocorticoids in patients with pemphigus has not been determined. Thus, approaches to glucocorticoid tapering vary. Our approach for a 70 kg adult is as follows: ●Once no new lesions have formed for seven days, we reduce prednisone from 1 mg/kg per day to 0.75 mg/kg per day. ●If at least seven days have elapsed since the first dose reduction and no new lesions have formed, we reduce the dose of prednisone to 0.5 mg/kgper day. ●If at least 14 days have elapsed since the reduction to 0.5 mg/kg per day and no new lesions have formed for at least one week, we reduce the dose of prednisone to 30 mg per day. ●Thereafter, we continue dose reductions in a stepwise manner with at least 14 days between each reduction and continue the requirement that no new lesions form within seven days prior to the next reduction. Our dose reduction series is as follows: 30, 25, 20, 15, 10, 7.5, 5, 2.5, and 0 mg per day. ●We continue adjuvant therapy with azathioprine or mycophenolate until prednisone has been completely discontinued, and eight weeks after successful discontinuation of prednisone, we begin to reduce the dose of the adjuvant medication. We reduce azathioprine by 50 mg every eight weeks, mycophenolate mofetil by 500 mg every eight weeks, or mycophenolate sodium by 360 mg every eight weeks until treatment cessation.

- 14. Pulsed glucocorticoids — Intravenous or oral pulsed glucocorticoids have been utilized for the treatment of pemphigus vulgaris. Treatment regimens have varied widely, and data comparing regimens that incorporate pulsed glucocorticoids with regimens that do not include pulsed glucocorticoids are limited to a few small studies that have or have not demonstrated benefits over various nonpulsed regimens. Adverse effects — Adverse effects, such as hypertension, hyperlipidemia, diabetes mellitus, osteoporosis, increased susceptibility to infections, gastrointestinal ulcers, and aseptic bone necrosis, may cause significant morbidity and mortality among patients who receive prolonged systemic glucocorticoid therapy. Hence, frequent patient follow-up and the implementation of appropriate preventive and therapeutic measures for glucocorticoid side effects are essential. NONSTEROIDAL ADJUVANT THERAPIES — Although systemic glucocorticoids are the mainstay of pemphigus treatment, concern for the serious adverse effects associated with prolonged, high-dose systemic glucocorticoid therapy have led to the use of nonsteroidal immunomodulatory agents as adjuvant therapies. Azathioprine and mycophenolate mofetil are the most common adjuvant agents utilized in the initial management of patients with pemphigus. Despite the frequent use of nonsteroidal agents for the purpose of minimizing glucocorticoid requirements, data on their efficacy for this indication are limited and some studies have yielded conflicting results. In addition, the value of combination therapy for improving patient outcomes is uncertain. Azathioprine — Azathioprine is the most common nonsteroidal immunomodulatory drug given to patients with pemphigus. Azathioprine has been used for this indication for decades. Efficacy — Randomized trials that have evaluated the use of azathioprine as an adjuvant to systemic glucocorticoids for patients with pemphigus include trials that have compared combination therapy with a systemic glucocorticoid and azathioprine, with treatment with a systemic glucocorticoid alone, or treatment with a systemic glucocorticoid plus another nonsteroidal immunosuppressive agent. Two randomized trials that evaluated the glucocorticoid-sparing effects of azathioprine have found conflicting results, and a beneficial effect of adjuvant therapy with azathioprine on patient outcomes remains to be proven: ●A randomized open-label trial of 120 patients with pemphigus vulgaris that compared four treatment regimens in which prednisolone (2 mg/kg per day up to a maximum of 120 mg per day followed by a taper) was given alone or in conjunction with another immunosuppressive agent supported the glucocorticoid-sparing effects of azathioprine (2.5 mg/kg per day for two months then 50 mg per day) .After one year, patients who received combination therapy with prednisolone and azathioprine had a significantly lower mean total dose of prednisolone than patients treated with prednisolone alone (7712 mg versus 11,631 mg). However, clinical outcomes were similar in the two groups. After one year, complete remission was attained by 77 percent of patients in the prednisolone only group and 80 percent of patients who received combination therapy. ●In a 12-month randomized trial in which 56 patients with a new diagnosis of pemphigus vulgaris were treated with prednisolone (2 mg/kg per day up to 120 mg per day followed by a taper) plus azathioprine (2.5 mg/kg per day) or prednisolone in a similar regimen plus a placebo pill, patients in both groups achieved statistically significant clinical improvement. A nonsignificant trend towards a lower mean disease activity score was detected in the combination therapy group at each

- 15. monthly assessment during the last six months of the trial .This difference achieved statistical significance when data from the last three months of therapy were jointly assessed. In contrast to the trial above, a significant difference in the mean total dose of prednisolone was not detected. The glucocorticoid-sparing effect of azathioprine was compared with other nonsteroidal immunosuppressants in a 2011 systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized trials published prior to 2009 [10]. The glucocorticoid-sparing effect of azathioprine appeared to be superior to the glucocorticoid-sparing effects of mycophenolate mofetil based upon the meta-analysis of two randomized trials that compared these agents Of note, the independent analysis of one of the included trials did not yield a significant difference in the glucocorticoid-sparing effect . Additional trials would be useful for clarifying the efficacy of azathioprine as a glucocorticoid-sparing agent and for comparing this drug with other therapies. Multiple uncontrolled studies have documented successful use of azathioprine in combination with systemic glucocorticoid therapy . Administration — Dosing of azathioprine is influenced by the level of activity thiopurine methyltransferase (TPMT), an enzyme involved in the degradation of azathioprine to inactive metabolites. Reduced TPMT activity is associated with an increased risk for azathioprine-induced myelosuppression. Recommendations for azathioprine dosing based upon TPMT activity vary .In general, adults with pemphigus and high TPMT activity can be treated with normal doses of azathioprine (up to 2.5 mg/kg [ideal body weight] per day), patients with intermediate or low TPMT activity should receive a lower maintenance dose (up to 0.5 to 1.5 mg/kg per day depending on level of enzyme activity), and patients with absent TPMT activity should not be treated with azathioprine .TPMT activity may be assessed through testing for the level of enzyme activity or genotyping. In patients with high TPMT activity, we typically begin treatment with 1 mg/kg (ideal body weight) per day of azathioprine. We increase the dose by increments of 0.5 mg/kg to reach a maintenance dose of 2.5 mg/kg per day within two to three weeks, provided serious toxicity is not detected. Adverse effects — Due to the risk for myelosuppression, close laboratory monitoring is necessary for patients treated with azathioprine. We typically monitor a complete blood count with differential, renal function tests and liver function tests at baseline, every two weeks for the first three months, and periodically (every two to three months) thereafter. In addition to myelosuppression, malignancy, gastrointestinal disorders, and infections are potential adverse effects of azathioprine therapy. Mycophenolate mofetil — Mycophenolate mofetil is an immunosuppressive agent that may be useful for pemphigus . The relatively favorable side effect profile of mycophenolate mofetil is an advantage of this agent. Efficacy — A few randomized trials have evaluated the effects of adjuvant treatment with mycophenolate mofetil on glucocorticoid requirements and patient outcomes. Although two randomized trials found a statistically significant reduction in glucocorticoid consumption in patients who received adjuvant mycophenolate mofetil compared with patients treated with a glucocorticoid alone ,another randomized trial failed to find a significant glucocorticoid-sparing effect .In addition, a meta- analysis of two randomized trials that compared the glucocorticoid-sparing effects of azathioprine and mycophenolate mofetil found that mycophenolate mofetil appeared to have inferior glucocorticoid-sparing effects .

- 16. A beneficial effect of adjuvant mycophenolate mofetil on the likelihood that patients will respond to glucocorticoid treatment has not been demonstrated in the available randomized trials. However, one trial found that adjuvant mycophenolate mofetil was associated with a longer duration of clinical remission . Randomized trials of mycophenolate mofetil in pemphigus are described in greater detail below: ●A randomized open-label trial of 120 patients with pemphigus vulgaris that compared four treatment regimens found that patients treated withprednisolone (2 mg/kg per day up to a maximum of 120 mg per day followed by a taper) and mycophenolate mofetil (2 g per day) had lower mean total doses of prednisolone than patients treated with prednisolone alone after one year (9798 versus 11,631 mg, respectively). A statistically significant difference in the rate of complete remission was not detected between the two groups. Complete remission occurred in 70 versus 77 percent of patients, respectively. ●A randomized trial of 94 patients with pemphigus vulgaris that compared treatment with oral prednisone (initial dose 1 to 2 mg/kg per day followed by a taper) plus mycophenolate mofetil (2 or 3 g per day), with oral prednisone given plus a placebo pill failed to find a significant difference in the proportion of responders; 40 of 58 patients in the mycophenolate mofetil group (69 percent) and 23 of 36 patients in the placebo group (64 percent) responded to treatment . Patients treated with mycophenolate mofetil had significantly lower total prednisone ingestion over the course of one year than patients in the placebo group (3220 versus 4450 mg, respectively). In addition, relapse was significantly more delayed in the mycophenolate group; 22 percent of mycophenolate-treated patients versus 45 percent of placebo-treated patients relapsed by 24 weeks after an initial response. A borderline statistically significant trend for faster response also was observed in the mycophenolate mofetil group (24 versus 31 weeks to initial response). ●A randomized trial of 47 patients with newly diagnosed pemphigus (36 with pemphigus vulgaris and 11 with pemphigus foliaceus) that compared treatment with methylprednisolone alone (initial dose equivalent to 1 mg/kg of prednisone then increased and tapered per clinical response) and in combination with mycophenolate mofetil (initial dose 3 g per day then reduced to 2 g per day) found no difference in the glucocorticoid-sparing effects, the rate of response, or remission rates . Administration — Doses of 2 g per day (taken as 1 g twice daily) are typically used when mycophenolate mofetil is added to systemic glucocorticoid therapy for the treatment of pemphigus in adults. Enteric-coated mycophenolate sodium is an alternative form of mycophenolate that is given to adults in a dose of 720 mg twice daily. Adverse effects — The most common side effects of mycophenolate mofetil are gastrointestinal complaints. Enteric-coated mycophenolate sodium may have some benefit for patient tolerance while maintaining the immunosuppressive effects . Pancytopenia is another important side effect of mycophenolate. A complete blood count with differential can be obtained at baseline and every two weeks during the first two to three months of therapy, then once monthly within the first year, and every three months thereafter . Renal function tests and liver function tests can be obtained at baseline, after one month, and periodically thereafter. Side effects of mycophenolate mofetil are reviewed in greater detail separately. Dapsone — Data on dapsone therapy for pemphigus are more limited than data for azathioprine and mycophenolate mofetil, and dapsone is less commonly utilized for this indication. However, based upon reports of efficacy in some patients and the favorable status of dapsone as a

- 17. nonimmunosuppressive therapy , some clinicians choose to use dapsone as a first-line adjuvant therapy in patients with pemphigus, particularly for patients with pemphigus foliaceus or IgA pemphigus. Efficacy — A 2009 review of case reports and case series identified 37 patients with pemphigus vulgaris and 18 patients with pemphigus foliaceus who were treated with dapsone (50 to 300 mg per day) with or without prednisone or other immunosuppressive therapies . Responses to dapsone were documented in 86 percent of the patients with pemphigus vulgaris and 78 percent of the patients with pemphigus foliaceus. The responders included 6 of 6 patients with pemphigus vulgaris and 9 of 14 patients with pemphigus foliaceus who received dapsone as monotherapy. A subsequent multicenter randomized trial that evaluated the efficacy of adjuvant dapsone (150 to 200 mg per day) for facilitating the tapering of systemic glucocorticoids in patients with pemphigus vulgaris that was well-controlled with a systemic glucocorticoid (with or without an adjuvant immunosuppressant), but refractory to glucocorticoid-tapering, failed to find a statistically significant effect . A reduction in the dose of prednisone to less than 7.5 mg per day was achieved within one year in 5 of 9 patients treated with adjuvant dapsone (56 percent) and 3 of 10 patients (30 percent) who received a placebo pill instead of dapsone as adjuvant therapy. Monotherapy with relatively high doses of dapsone (200 to 300 mg per day) appeared to be effective as an initial treatment for pemphigus foliaceus in a small series. Five of the nine patients had at least 50 percent reduction in the extent of the disease within 15 days. However, four patients failed to respond to dapsone treatment, and three patients required discontinuation of therapy; one ceased treatment due to toxic hepatitis and hemolytic anemia, and two ceased treatment due to methemoglobinemia. Additional studies are necessary to determine the role of dapsone in the treatment of pemphigus. Administration — Target doses for dapsone for pemphigus range from 50 to 200 mg per day. Treatment is usually initiated at a low dose (eg, 25 or 50 mg per day in adults) and titrated upward as tolerated. Adverse effects — Hemolysis is an expected side effect of dapsone that occurs to some degree in all treated patients. Patients with glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase (G6PD) deficiency have an elevated risk for severe hemolytic anemia related to dapsone therapy. Thus, we evaluate patients for G6PD deficiency prior to the initiation of dapsone. Additional adverse effects of dapsone include methemoglobinemia, agranulocytosis, hypersensitivity, and motor neuropathy. Close hematologic monitoring for hemolysis and agranulocytosis is essential during treatment. Other agents — Other drugs that have been used as adjuvants to systemic glucocorticoids for the treatment of pemphigus are methotrexate (10 to 25 mg per week), cyclosporine (2.5 to 5 mg/kg per day), and combination therapy with a tetracycline derivative and nicotinamide. ●Methotrexate – No randomized trials have evaluated the efficacy of methotrexate as an adjuvant therapy. Support for this drug is derived from uncontrolled studies and case series . In a retrospective study of 23 patients with pemphigus vulgaris for whom methotrexate (up to 15 to 25 mg per week) was added to systemic glucocorticoid therapy, 21 patients (91 percent) had improvement in blistering after the addition of methotrexate and 16 patients (70 percent) eventually were able to discontinue prednisone completely (mean time to discontinuation of prednisone therapy 18 months) . In a separate case series, six of nine patients treated with adjuvant methotrexate (10 to

- 18. 17.5 mg per week) for pemphigus vulgaris were able to discontinue prednisone within six months . These observations suggest benefit of methotrexate as a glucocorticoid-sparing therapy. ●Cyclosporine – Although efficacy of cyclosporine was reported in case series of patients with pemphigus , two randomized trials did not demonstrate an advantage of cyclosporine therapy [53,54]. ●Tetracyclines and nicotinamide – Limited data from retrospective studies suggest that combination therapy with a tetracycline derivative (eg, tetracycline, doxycycline, or minocycline) and nicotinamide (also known as niacinamide), a well-tolerated regimen often used for bullous pemphigoid, may be a useful adjuvant to systemic glucocorticoid therapy for pemphigus . The typical adult dose for tetracycline is 500 mg four times daily; doxycycline and minocycline are given as 100 mg twice daily and nicotinamide is usually given as 500 mg three times per day. Of note, a small uncontrolled prospective study found poor treatment results when tetracycline and nicotinamide were given as the primary therapeutic regimen for pemphigus rather than as a glucocorticoid-sparing therapy . REFRACTORY DISEASE — The management of pemphigus vulgaris and pemphigus foliaceus that is refractory to initial therapy is reviewed separately. ASSESSING THE RESPONSE TO THERAPY — Patients with pemphigus should be followed closely to evaluate disease activity and the response to treatment, as well as to assess for adverse effects of therapy. Because pemphigus is a dynamic disease, management often requires frequent adjustments of therapy [1]. The response to treatment primarily is assessed through clinical observation. Cessation of new blister formation, an absent Nikolsky sign , and healing of old lesions with re-epithelization indicate that disease activity is under control. Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay titers for desmoglein 1 and desmoglein 3 autoantibodies may be helpful as an adjunct to clinical assessment since titers may correlate with disease activity . However, the correlation is not perfect, and ELISA results must be interpreted carefully. ADDITIONAL MEASURES Skin care — Local skin care measures may help to improve patient comfort and reduce the risk for infection. Clinicians or patients should puncture and drain large blisters in a sterile manner. The epithelial roof of the blister should be left intact after draining to serve as wound covering and to reduce the risk for infection. In our experience, twice daily application of a high potency topical corticosteroid (eg, clobetasol propionate ointment or gel) directly to erosions can be a useful adjunct to systemic therapy for persistent, active, hard-to-treat pemphigus lesions [1]. Intralesional injection of triamcinolone acetonide (20 mg/mL)may also help to heal persistent lesions [1]. Wound areas should be kept clean to reduce the risk for infection. Erosions may be covered with antibiotic ointment or a bland emollient (eg, petrolatum), with or without a nonadhesive wound dressing. Patients should be informed about the warning signs of infection to facilitate prompt diagnosis and early treatment.

- 19. Of note, the possibility of secondary infection (particularly herpes simplex virus infection) should be considered for lesions that fail to respond as expected to therapy, and infection should be treated appropriately if detected . Due to the inhibitory effects of herpes simplex virus infection on healing of skin lesions in patients with pemphigus, we often initiate prophylactic antiviral therapy after an episode of pemphigus complicated by herpes simplex infection. Management of oral symptoms — Oral mucosal involvement in pemphigus vulgaris causes discomfort, which may be severe. In addition to treatment of the disease process with systemic therapy, we have found the following measures useful for reducing symptoms during active disease: ●Avoidance of spicy, sharp, abrasive, or very hot foods ●Application of topical anesthetics as needed (eg, viscous lidocaine 2% solution, lidocaine 2% gel) ●Oral hygiene (teeth should be brushed twice daily with a soft-bristle brush with a bland toothpaste and flossed daily; additionally, professional dental cleanings may be of use) In our experience, topical corticosteroids help to improve oral symptoms of pemphigus in some patients. We often utilize a medium or high potency topical corticosteroid (eg, triamcinolone 0.1% in dental paste or fluocinonide 0.05% gel applied with gauze occlusion) or a corticosteroid mouthwash (eg, 5 mL ofdexamethasone 0.5 mg/5 mL solution as a mouth rinse) two to three times per day. We have also found topical tacrolimus 0.1% ointment useful. Patients may find topical anesthetics (eg, viscous lidocaine) helpful for managing symptoms. Candida infection is a common occurrence in patients with mucosal pemphigus vulgaris who are treated with systemic glucocorticoids. We prescribe oralnystatin swish and swallow (or swish and spit) or clotrimazole lozenges as prophylaxis for patients receiving systemic glucocorticoids, or monitor patients closely for the development of oropharyngeal candidal infection and treat if infection develops.