2 Facilitating Diversity in Learning Course Resource Book

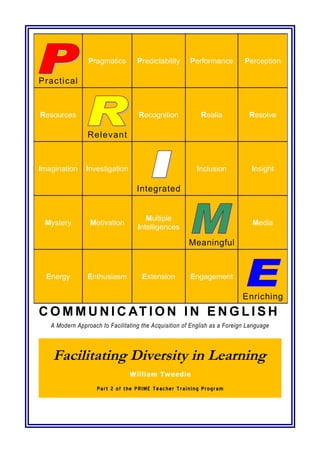

- 1. Pragmatics Predictability Performance Perception Practical Resources Recognition Realia Resolve Relevant Imagination Investigation Inclusion Insight Integrated Multiple Mystery Motivation Media Intelligences Meaningful Energy Enthusiasm Extension Engagement Enriching C O M M U N I C AT I O N I N E N G L I S H A Modern Approach to Facilitating the Acquisition of English as a Foreign Language Facilitating Diversity in Learning William Tweedie Part 2 of the PRIME Teacher Training Program

- 2. Facilitating Diversity in Learning Making Learning Fun through Understanding Multiple Intelligences Course Reference Book William Tweedie © 2005 - 2010 Kenmac Educan International & William M Tweedie TABLE OF CONTENTS 2

- 3. FACILITATING DIVERSITY .................................................................................................................4 HOW WE LEARN..............................................................................................................................4 IT'S NOT HOW SMART YOU ARE - IT'S HOW YOU ARE SMART!..........................................................6 THE NINE TYPES OF INTELLIGENCE...................................................................................................7 GARDNER’S EIGHT CRITERIA FOR IDENTIFYING INTELLIGENCE..........................................................8 LEARNING STYLES AND YOUR STUDENTS.........................................................................................9 WHAT ARE “MULTIPLE INTELLIGENCES”?.......................................................................................12 NEW AND EMERGING THEORIES OF INTELLIGENCE.........................................................................14 THE THEORY OF MULTIPLE INTELLIGENCES.....................................................................................17 VARIATIONS OF THINKING STYLES.................................................................................................22 MATCHING TEACHING STYLES WITH LEARNING STYLES IN EAST ASIAN CONTEXTS..........................24 HELPING STUDENTS IDENTIFY LEARNING STYLES............................................................................31 INFORMATION AND QUESTIONNAIRES FOR ASSESSING LEARNING STYLES AND PREFERENCES...........................................................................33 MAKE LEARNING FUN THROUGH MULTIPLE INTELLIGENCES...........................................................44 ASSESSMENT AND EVALUATION ...................................................................................................50 EIGHT SMARTS IN DESIGNING ELT MATERIALS ..............................................................................52 CLEAR RUBRICS MOVE STUDENTS BEYOND APATHY TO UNDERSTANDING ....................................57 ASSESSMENTS THAT RECOGNIZE AND ENHANCE DIVERSITY ..........................................................59 CHARACTERISTICS OF EFFECTIVE TEACHING...................................................................................62 ENTHUSIASM RATING....................................................................................................................65 “CATCH A HUMAN STAR AND . . .” ................................................................................................66 MULTIPLE INTELLIGENCES RESOURCES...........................................................................................69 Articles are the property of the authors and copyright owners. Permission is granted for reproduction. Please site the authors and source if reproducing. 3

- 4. Facilitating Diversity Making Learning Fun through Multiple Intelligences (MI) by William M. Tweedie Part 1 - Introduction to MI Theory A. What are learning styles? B. What are thinking styles? C. What are Multiple Intelligences? D. What is the relationship between the two concepts? E. What are your intelligence strengths? a. Survey of your strengths. b. Does it affect your teaching style? c. Circle of Knowledge Activity i. What are the Nine Intelligences? ii. What are three characteristics of learners using each? Part 2 - Theory into Practice A. MI and Motivation B. The seven levels of engagement C. Helping students identify their learning styles – a first step to engaging the psychological and emotional ‘selves’ of students a. Assessments D. Making Learning Fun through MI a. An example activity for MI group building – It’s in the Bag Part 3 - Lesson Plans A. Sample MI Lesson Plan a. Developing a Lesson Plan Group Activity b. The case for rubrics Part 4 - Summary and Conclusion A. Characteristics of effective teaching – a model based on the Teaching Behaviors Inventory created by Harry Murray at the University of Western Ontario. B. How enthusiastic are YOU? “Go with your cousin Courage and his sister Success will not be far behind.” How We Learn 4

- 5. By ALISON GOPNIK New York Times: Published: January 16, 2005 o here's the big question: if children who don't even go to school learn so easily, why do children who go to school seem to have such a hard time? Why can children solve problems that challenge computers but stumble on a third-grade reading test? When we talk about learning, we really mean two quite different things, the process of discovery and of mastering what one discovers. All children are naturally driven to create an accurate picture of the world and, with the help of adults to use that picture to make predictions, formulate explanations, imagine alternatives and design plans. Call it ''guided discovery.'' If this kind of learning is what we have in mind then one answer to the big question is that schools don't teach the same way children learn. As in the gear-and-switch experiments, children seem to learn best when they can explore the world and interact with expert adults. For example, Barbara Rogoff, professor of psychology at the University of California at Santa Cruz, studied children growing up in poor Guatemalan Indian villages. The youngsters gradually mastered complex skills like preparing tortillas from scratch, beginning with the 2-year-old mimicking the flattening of dough to the 10-year-old entrusted with the entire task. They learned by watching adults, trying themselves and receiving detailed corrective feedback about their efforts. Mothers did a careful analysis of what the child was capable of before encouraging the next step. This may sound like a touchy-feely progressive prescription. But a good example of such teaching in our culture is the stern but beloved baseball coach. How many school teachers are as good at essay writing, science or mathematics as the average coach is at baseball? And even when teachers are expert, how many children ever get to watch them work through writing an essay or designing a scientific experiment or solving an unfamiliar math problem? Imagine if baseball were taught the way science is taught in most inner-city schools. Schoolchildren would get lectures about the history of the World Series. High school students would occasionally reproduce famous plays of the past. Nobody would get in the game themselves until graduate school. But there is another side to the question. In guided discovery -- figuring out how the world works or unravelling the structure of making tortillas -- children learn to solve new problems. But what is expected in school, at least in part, involves a very different process: call it ''routinized learning.'' Something already learned is made to be second nature, so as to perform a skill effortlessly and quickly. The two modes of learning seem to involve different underlying mechanisms and even different brain regions, and the ability to do them develops at different stages. Babies are as good at discovery as the smartest adult -- or better. But routinized learning evolves later. There may even be brain changes that help. There are also tradeoffs: Children seem to learn new things more easily than adults. But especially through the school-age years, knowledge becomes more and more engrained and automatic. For that reason, it also becomes harder to change. In a sense, routinized learning is less about getting smarter than getting stupider: it's about perfecting mindless procedures. This frees attention and thought for new discoveries. The activities that promote mastery may be different from the activities that promote discovery. What makes knowledge automatic is what gets you to Carnegie Hall -- practice, practice, practice. In some settings, like the Guatemalan village, this happens naturally: make tortillas every day and you'll get good at it. In our culture, children rich and poor grow highly skilled at video games they play for hours. But in school we need to acquire unnatural skills like reading and writing. These are meaningless in themselves. There is no intrinsic discovery in learning artificial mapping between visual symbols and sounds, and in the natural environment no one would ever think of looking for that sort of mapping. On 5

- 6. the other hand, mastering these skills is absolutely necessary, allowing us to exercise our abilities for discovery in a wider world. The problem for many children in elementary school may not be that they're not smart enough but that they're not stupid enough. They haven't yet been able to make reading and writing transparent and automatic. This is particularly true for children who don't have natural opportunities to practice these skills, learning in chaotic and impoverished schools and leading chaotic and impoverished lives. But routinized learning is not an end in itself. A good coach may well make his players throw the ball to first base 50 times or swing again and again in the batting cage. That will help, but by itself it won't make a strong player. The game itself -- reacting to different pitches, strategizing about base running -- requires thought, flexibility and inventiveness. Children would never tolerate baseball if all they did was practice. No coach would evaluate a child, and no society would evaluate a coach, based on performance in the batting cage. What makes for learning is the right balance of both learning processes, allowing children to retain their native brilliance as they grow up. Alison Gopnik is co-author of ''The Scientist in the Crib'' and professor of psychology at the University of California at Berkeley. It's Not How Smart You Are - It's How You Are Smart! 6

- 7. Howard Gardner's Theory of Multiple Intelligences What parent can not see gleaming rays of genius in their child? And yet, how many children come to school and demonstrate their own unique genius? There was a time when it might have been a joke to suggest "Every parent thinks their kid's a genius." But research on human intelligence is suggesting that the joke may be on educators! There is a constant flow of new information on how the human brain operates, how it differs in function between genders, how emotions impact on intellectual acuity, even on how genetics and environment each impact our children’s' cognitive abilities. While each area of study has its merits, Howard Gardner of Harvard University has identified different KINDS of intelligence we possess. This has particularly strong ramifications in the classroom, because if we can identify children's different strengths among these intelligences, we can accommodate different children more successfully according to their orientation to learning. Thus far Gardner has identified nine intelligences. He speculates that there may be many more yet to be identified. Time will tell. These are the paths to children's learning teachers can address in their classrooms right now. Teachers are now working on assimilating this knowledge into their strategies for helping children learn. While it is too early to tell all the ramifications for this research, it is clear that the day is past where educators teach the text book and it is the dawn of educators teaching each child according to their orientation to the world. By Walter McKenzie copyright 1999 Walter McKenzie The Nine Types of Intelligence 7

- 8. • VISUAL/SPATIAL - children who learn best visually and organizing things spatially. They like to see what you are talking about in order to understand. They enjoy charts, graphs, maps, tables, illustrations, art, puzzles, costumes - anything eye catching. • VERBAL/LINGUISTIC - children who demonstrate strength in the language arts: speaking, writing, reading, and listening. These students have always been successful in traditional classrooms because their intelligence lends itself to traditional teaching. • MATHEMATICAL/LOGICAL - children who display an aptitude for numbers, reasoning and problem solving. This is the other half of the children who typically do well in traditional classrooms where teaching is logically sequenced and students are asked to conform. • BODILY/KINESTHETIC - children who experience learning best through activity: games, movement, hands-on tasks, building. These children were often labeled "overly active" in traditional classrooms where they were told to sit and be still! • MUSICAL/RHYTHMIC - children who learn well through songs, patterns, rhythms, instruments and musical expression. It is easy to overlook children with this intelligence in traditional education. • INTRAPERSONAL - children who are especially in touch with their own feelings, values and ideas. They may tend to be more reserved, but they are actually quite intuitive about what they learn and how it relates to them. • INTERPERSONAL - children who are noticeably people oriented and outgoing, and do their learning cooperatively in groups or with a partner. These children may have typically been identified as "talkative" or " too concerned about being social" in a traditional setting. • NATURALIST - children who love the outdoors, animals, field trips. More than this, though, these students love to pick up on subtle differences in meanings. The traditional classroom has not been accommodating to these children. • EXISTENTIALIST - children who learn in the context of where humankind stands in the "big picture" of existence. They ask "Why are we here?" and "What is our role in the world?" This intelligence is seen in the discipline of philosophy. By Walter McKenzie copyright 1999 Walter McKenzie Gardner’s Eight Criteria for Identifying Intelligence 8

- 9. 1. Isolation of Brain Function - as medicine studies isolated brain functions through cases of brain injury and degenerative disease; we are able to identify actual physiological locations for specific brain functions. A true intelligence will have its function identified in a specific location in the human brain. 2. Prodigies, Idiot Savants and Exceptional Individuals - human record of genius, such as, Mozart being able to perform on the piano at the age of four and Dustin Hoffman's "Rainman" character being able to calculate dates accurately down to the day of the week indicate that there are specific human abilities which can demonstrate themselves to high degrees in unique cases. Highly developed examples of a true intelligence are rare occurrences. 3. Set of Core Operations - there is an identifiable set of procedures and practices which is unique to each of the true intelligences. 4. Developmental History with an Expert End Performance - as clinical psychologists continue to study the developmental stages of human growth and learning, a clear pattern of developmental history of the human mind is being documented. A true intelligence has an identifiable set of stages of growth with a Mastery Level which exists as an end state in human development. We can see examples of people who have reached the Mastery level in each of the intelligences. 5. Evolutionary History - as cultural anthropologists continue to study the history of human evolution, there is adequate evidence that our species has developed intelligence over time through human experience. A true intelligence can have its development traced through the evolution of Homosapiens. 6. Supported Psychological Tasks - clinical psychologists can identify sets of tasks for different domains of human behaviour. A true intelligence can be identified by specific tasks which can be carried out, observed and measured. 7. Supported Psychometric Tasks - the use of psychometric instruments to measure intelligence (such as I.Q. tests) have traditionally been used to measure only specific types of ability. However, these tests can be designed and used to identify and quantify true unique intelligences. The Multiple Intelligence theory does not reject psychometric testing for specific scientific study. 8. Encoded into a Symbol System - humans have developed many kinds of symbol systems over time for varied disciplines. A true intelligence has its own set of images it uses which are unique to it and are important in completing its identified set of tasks. Remember, everyone has ALL the intelligences. The intelligences are not mutually exclusive - they act in consort. MI Theory was not developed to exclude individuals, but to allow all people to contribute to society through there own strengths! -Walter McKenzie Learning Styles and Your Students 9

- 10. Summary by William M. Tweedie, adapted from a variety of sources If you've ever watched a group of students interact, you've probably noticed that different students like to do different things. Why is this? Many educators and student psychologists believe that each student has a particular learning style that affects how he or she most effectively interacts with the world to learn and grow. Knowing the learning styles of your students can help you choose activities that will help your students learn and grow most effectively. The study of Learning Styles and Multiple Intelligences (Frames of Mind - Gardner, 1983) is still developing and there are different interpretations of the two concepts and the relationship between them. For now, it is important to simply recognize that not everybody learns or acquires a second language through a single method or set of techniques. The following summary presents ideas accepted by most educators. Learning Styles: What They Are Simply put, a learning style is the preferred way a person acquires knowledge. It is not what a person learns, but how a person learns. A student’s learning style is a reflection of the development of his intelligences at any given moment. Eight different intelligences have been identified through the work of Howard Gardner. Although we are capable of using them all, it seems most of us rely on only one or two. As a result, we develop our own particular approach to learning (and in many cases to teaching) based on our favoured learning style(s). Educators and psychologists commonly define the eight different learning styles as follows: Verbal - Linguistic - Linguistic learners relate to language in both its written and spoken form. They learn best through poetry, storytelling, grammar, abstract reasoning, metaphors, similes, etc. Logical - Mathematical - Logical-mathematical learners focus on different types of reasoning and logic. They like to make observations, draw conclusions, make judgments, and formulate hypotheses. Visual - Spatial - Spatial learners like to deal with visualization and imagery. Students with this learning style learn well through painting, drawing, sculpturing, designing, etc. Intrapersonal - Intrapersonal learners focus on situations that require them to reflect upon themselves. They like higher-order thinking and reasoning, self-reflection, spirituality, and the awareness and expression of feelings. Interpersonal - Interpersonal learners engage in verbal and nonverbal communication with others. They learn best when working in groups cooperatively, reacting to others' moods and feelings, and understanding the perspective of others. Bodily - Kinaesthetic - Bodily Kinaesthetic learners like physical movement. They learn well when involved in physical exercise and in forms of expression like dance, mime, drama, or role-playing. Musical - Rhythmical - Musical learners have the capacity to recognize rhythm and tone patterns, and sensitivity to sounds from the human voice and musical instruments. They like to interact with music. Naturalist/Environmental - A relatively new category of style, the outdoor learner is inspired to learn in natural surroundings. Their curiosity is aroused by the earth’s physical characteristics and beauty. Verbal - Linguistic - Linguistic learners relate to language in both its written and spoken form. They learn best through poetry, storytelling, grammar, abstract reasoning, metaphors, similes, etc. Learning Styles: How to Use Them Understanding that your students’ have individual learning styles can help you support what they do in the classroom. By providing activities that suit their learning styles, you provide optimum opportunities for them to learn. For example, you might want to teach mathematical concepts in ways best suited to your students’ learning styles. If a student is a more musical learner, singing number songs might be useful. 10

- 11. Linguistic learners might best learn mathematical concepts from stories in which numbers figure prominently. Interpersonal learners might benefit from more social activities such as cooking from a recipe. Once you recognize (ideally, through formal analysis as well as informal observation) a variety of the learning styles in your students, provide activities that will reinforce them. In doing so, it will be important to show how things related to their careers are evident in all sorts of different activities, including music, art, and literature. In that way you can ensure that your students’ interests are tapped and still focus on important educational points. Learning Styles: Things to Think About As you start to think about your students’ learning styles, you might want to keep these points in mind: Your students may have several different learning styles that work best for each of them. Although a particular learning style may be dominant in any individual or group of students, it is still important that you provide a variety of activities. In that way, you will continue to develop their other intelligences and aspects of personalities. Learning styles can be used both to teach and reinforce concepts. Try using one approach to teach your students a concept, and then use a different one to reinforce it. For example, you might want to use a linguistic approach, such as a story, to teach the vocabulary or idea of some aspect of their career studies or other interests, and then have your students draw a picture that reflects the concept in art. Regardless of your students’ ages and ability levels, your course content and objectives, or the focus of an individual lesson, it is important to keep in mind the fact that everyone of us has a different style or combination of styles that best facilitates learning anything. As language is such a vital personal tool linked directly with our emotional and psychological selves, having the awareness of and doing your best to accommodate your students’ learning styles is perhaps more important for you as language learning facilitators than for ‘teachers’ of other subjects. What These Learners Like to Do, Are Good At, What Works For Them The Linguistic Learner likes to: read, write and tell stories; is good at: memorizing names, places, dates and trivia; learns best by: saying, hearing and seeing words. Logical/Mathematical Learner likes to: do experiments, figure things out, work with numbers, ask questions and explore patterns and relationships; is good at: math, reasoning, logic and problem solving; learns best by: categorizing, classifying and working with abstract patterns/relationships. Spatial Learner likes to: draw, build, design and create things, daydream, look at pictures/slides, watch movies and play with machines; is good at: imagining things, sensing changes, mazes/puzzles and reading maps, charts; learns best by: visualizing, dreaming, using the mind's eye and working with colors/pictures. Musical Learner likes to: sing, hum tunes, listen to music, play an instrument and respond to music; is good at: picking up sounds, remembering melodies, noticing pitches/rhythms and keeping time; learns best by: rhythm, melody and music. Bodily/Kinaesthetic Learner likes to: move around, touch and talk and use body language; is good at: physical activities (sports/dance/acting) and crafts; learns best by: touching, moving, interacting with space and processing knowledge through bodily sensations. Naturalistic Learner likes to: be outside, with animals, geography, and whether; interacting with the surroundings; is good at: categorizing, organizing a living area, planning a trip, preservation, and conservation; learns best by: studying natural phenomenon, in a natural setting, learning about how things work. Interpersonal Learner likes to: have lots of friends, talk to people and join groups; is good at: understanding people, leading others, organizing, communicating, manipulating and mediating conflicts; learns best by: sharing, comparing, relating, cooperating and interviewing. 11

- 12. Intrapersonal Learner likes to: work alone and pursue own interests; is good at: understanding self, focusing inward on feelings/dreams, following instincts, pursuing interests/goals and being original; learns best by: working alone, individualized projects, self-paced instruction and having own space. SPACE TO ACCOMMODATE YOUR LEARNING STYLE: Draw, Write, Calculate, Scribble, Make music, Consider the space, Talk about this space with friends, Plan your next vacation! What are “Multiple Intelligences”? By William M. Tweedie, adapted from a variety of sources 12

- 13. Multiple Intelligences are eight different intellectual abilities and sets of skills. What are these intellectual abilities and skills? Visual/Spatial Intelligence The ability to perceive the visual: These learners tend to think in pictures and need to create vivid mental images to retain information. They enjoy looking at maps, charts, pictures, videos, and movies. Their skills include: puzzle building, reading, writing, understanding charts and graphs, a good sense of direction, sketching, painting, creating visual metaphors and analogies (perhaps through the visual arts), manipulating images, constructing, fixing, designing practical objects, interpreting visual images. Possible Career Paths: Navigators, sculptors, visual artists, inventors, architects, interior designers, mechanics, engineers Verbal/Linguistic Intelligence The ability to use words and language: These learners have highly developed auditory skills and are generally elegant speakers. They think in words rather than pictures. Their skills include: listening, speaking, writing, story telling, explaining, teaching, using humour, understanding the syntax and meaning of words, remembering information, convincing someone of their point of view, analyzing language usage. Possible Career Paths: Poet, journalist, writer, teacher, lawyer, politician, translator Logical/Mathematical Intelligence The ability to use reason, logic and numbers: These learners think conceptually in logical and numerical patterns making connections between pieces of information. Always curious about the world around them, these learners ask lots of questions and like to do experiments. Their skills include: problem solving, classifying and categorizing information, working with abstract concepts to figure out the relationship of each to the other, handling long chains of reason to make local progressions, doing controlled experiments, questioning and wondering about natural events, performing complex mathematical calculations, working with geometric shapes Possible Career Paths: Scientists, engineers, computer programmers, researchers, accountants, mathematicians Bodily/Kinaesthetic Intelligence The ability to control body movements and handle objects skilfully: These learners express themselves through movement. They have a good sense of balance and eye-hand co-ordination. (E.g. ball play, balancing beams). Through interacting with the space around them, they are able to remember and process information. Their skills include: Dancing, physical co-ordination, sports, hands on experimentation, using body language, crafts, acting, miming, using their hands to create or build, expressing emotions through the body Possible Career Paths: Athletes, physical education teachers, dancers, actors, firefighters, artisans Musical/Rhythmic Intelligence 13

- 14. The ability to produce and/or appreciate music: These musically inclined learners think in sounds, rhythms and patterns. They immediately respond to music either appreciating or criticizing what they hear. Many of these learners are extremely sensitive to environmental sounds (e.g. crickets, bells, dripping taps). Their skills include: Singing, whistling, playing musical instruments, recognizing tonal patterns, composing music, remembering melodies, understanding the structure and rhythm of music Possible Career Paths: Musician, disc jockey, singer, composer Interpersonal Intelligence The ability to relate to and understand others: These learners try to see things from other people's point of view in order to understand how they think and feel. They often have an uncanny ability to sense feelings, intentions and motivations. They are great organizers, although they sometimes resort to manipulation. Generally they try to maintain peace in group settings and encourage co-operation. They use both verbal (e.g. speaking) and non-verbal language (e.g. eye contact, body language) to open communication channels with others. Their skills include: seeing things from other perspectives (dual-perspective), listening, using empathy, understanding other people's moods and feelings, counselling, co-operating with groups, noticing people's moods, motivations and intentions, communicating both verbally and non- verbally, building trust, peaceful conflict resolution, establishing positive relations with other people. Possible Career Paths: Counsellor, salesperson, politician, business person Intrapersonal Intelligence The ability to self-reflect and be aware of one's inner state of being: These learners try to understand their inner feelings, dreams, relationships with others, and strengths and weaknesses. Their Skills include: Recognizing their own strengths and weaknesses, reflecting and analyzing themselves, awareness of their inner feelings, desires and dreams, evaluating their thinking patterns, reasoning with themselves, understanding their role in relationship to others Possible Career Paths: Researchers, theorists, philosophers Environmental/Naturalistic Intelligence The ability to appreciate and learn from the environment and nature: These learners have the ability to understand and appreciate the physical properties and wonders of the natural world. Their Skills include: Geography - categorizing animals, plants, rocks, etc. They understand and organize for conservation and preservation. They are usually very aware of the relationships between people and the environment. Possible Career Paths: Forest rangers, meteorologists, conservationists, biologists, geologists New and Emerging Theories of Intelligence 14

- 15. Originally prepared by: Kristin Garrigan and Jonathan Plucker (fall 2001) Revised Indiana State University: www.indiana.edu Introduction You cannot pick up a magazine today without seeing an article regarding intelligence or intelligences. The study of intelligence has proved to be a continuously evolving, dynamic field, with the breadth of the field expanding rapidly over the past 25 - 30 years. Many individuals, such as Gardner, Naglieri, and Goleman, argue that our view of human intelligence is far too narrow, leading the way to an expanded view of what intelligence is and what constitutes an intelligence. Several of the new and emerging intelligences are noted in the following sections. The Theory of Multiple Intelligences In the early 1980s, Howard Gardner opened the window to multiple intelligences (MI). Prof. Gardner claimed that MI theory illuminates the fact that humans exist in a multitude of contexts and that these contexts both call for and nourish different arrays and assemblies of intelligence. Many psychologists have expounded on this notion and today the number of quantifiable intelligences extends beyond that of Gardner's initial seven multiple intelligences. Sternberg's Conceptions Robert J. Sternberg has devoted much of his career to the study of various conceptions of human intelligence. Starting with his Triarchic Theory of Human Intelligence (Sternberg, 1985), he has expanded on his view of human ability and success. Successful intelligence is defined as that set of mental abilities used to achieve one's goals in life, given a socio-cultural context, through adaptation to, selection of, and shaping of environments. Successful intelligence involves three aspects that are interrelated but largely distinct: analytical, creative, and practical thinking (Sternberg, 1998). Practical Intelligence is the ability to size up a situation well, to be able to determine how to achieve goals, to display awareness to the world around you, and to display interest in the world at large (Sternberg, 1990; Sternberg et al., 2000; Wagner, 2000). Prof. Sternberg is working on several projects that examine the interrelation of his various conceptions of ability in applied settings. Moral Intelligence Moral Intelligence is the ability to distinguish between right and wrong. Broadly conceived, moral intelligence represents the ability to make sound decisions that benefit not only yourself, but others around you (Coles, 1997; Hass, 1998). Social Intelligence Interpersonal intelligence is the ability to understand other people: what motivates them, how they work, how to work cooperatively with them. Successful salespeople, politicians, teachers, clinicians, and religious leaders are all likely to be individuals with high degrees of interpersonal intelligence. At the same time, social intelligence probably draws on specific internal (Gardner would say intrapersonal) abilities. For example, in a recent study of incompetence, Kruger and Dunning (1999) found that incompetent people assessed themselves as being highly competent. This lack of ability to self-assess may be due to a combination of internal (poor metacognition) and external factors (poor ability to compare oneself to others). Social intelligence appears to be receiving the most attention in the management and organizational psychology literatures (e.g., Hough, 2001; Riggio, Murphy, & Pirozzolo, 2002). Emotional Intelligence Emotional intelligence, on the other hand, "is a type of social intelligence that involves the ability to monitor one's own and others' emotions, to discriminate among them, and to use the information to 15

- 16. guide one's thinking and actions" (Mayer & Salovey, 1993, p. 433). According to Goleman (1995), "Emotional intelligence, the skills that help people harmonize, should become increasingly valued as a workplace asset in the years to come." (p. 160). EL may subsume Gardner's inter- and intrapersonal intelligences, and involves abilities that may be categorized into five domains (Salovey & Mayer, 1990): • Self-awareness: Observing yourself and recognizing a feeling as it happens. • Managing emotions: Handling feelings so that they are appropriate; realizing what is behind a feeling; finding ways to handle fears and anxieties, anger, and sadness. • Motivating oneself: Channelling emotions in the service of a goal; emotional self control; delaying gratification and stifling impulses. • Empathy: Sensitivity to others' feelings and concerns and taking their perspective; appreciating the differences in how people feel about things. • Handling relationships: Managing emotions in others; social competence and social skills. Additional perspectives on EI are available in Bar-On and Parker (2000). Summary In this Hot Topic, we attempted to provide a brief overview of the major categories of new and emerging conceptions of intelligences. This list is not meant to be exhaustive, and we refer interested readers to the recent special issue of the journal, Roeper Review (April 2001), which addressed these and other new conceptions. References Bar-On, R., & Parker, J. D. A. (Eds.) (2000). The handbook of emotional intelligence: Theory, development, assessment, and application at home, school, and in the workplace. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. Coles, R. (1997). The moral intelligence of children: How to raise a moral child. New York: NAL/Dutton. Dweck, C. S., Chiu, C., & Hong, Y. (1995). Implicit theories and their role in judgments and reactions: A world from two perspectives. Psychological Inquiry, 6, 267-285. Gardner, H. (1993). Multiple intelligences. New York: BasicBooks. Goleman, D. (1995). Emotional intelligence. New York: Bantam Books. Hass, A. (1998). Doing the right thing: Cultivating your moral intelligence. New York: Hardcover. Hough, L. M. (2001). I/Owes its advances to personality. In B. W. Roberts & R. Hogan (Eds.), Personality psychology in the workplace. Decade of behaviour (pp. 19-44). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. Kruger, J., & Dunning, D. (1999). Unskilled and unaware of it: How difficulties in recognizing one's own incompetence lead to inflated self-assessments. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 77, 1121-1134. Mayer, J. D. & Salovey, P. (1993). The intelligence of emotional intelligence. Intelligence, 17, 433-442. Riggio, R. E., Murphy, S. E., & Pirozzolo, F. J. (Eds.). (2002). Multiple intelligences and leadership. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. 16

- 17. Salovey, P. & Mayer, J. D. (1990). Emotional intelligence. Imagination, Cognition, and Personality, 9, 185-211. Sternberg, R. J. (1998). Principles of teaching for successful intelligence. Educational Psychologist, 33, 65-71. Sternberg, R. J. (1990). Handbook of human intelligence. New York: Cambridge University Press. Sternberg, R. J., Forsythe, G. B., Hedlund, J., Horvath, J. A., Wagner, R. K., Williams, W. M., Snook, S. A., & Grigorenko, E. L. (2000). Practical intelligence in everyday life. New York: Cambridge University Press. Wagner, R. K. (2000). Practical intelligence. In R. J. Sternberg (Ed.), Handbook of intelligence (pp. 380-395). New York: Cambridge University Press. Prepared by Kristin Garrigan and Jonathan Plucker. The Theory of Multiple Intelligences Originally prepared by: Kristin Garrigan and Jonathan Plucker (fall 2001) Revised Indiana State University: www.indiana.edu Development of MI Theory 17

- 18. After years of research, Howard Gardner proposed a new theory and definition of intelligence in his 1983 book entitled Frames of Mind: The Theory of Multiple Intelligences. The basic question he sought to answer was: Is intelligence a single thing or various independent intellectual faculties? Gardner is Professor of Cognition and Education at the Harvard Graduate School of Education. He also holds an adjunct faculty post in psychology at Harvard and in neurology at Boston University School of Medicine. He is best known for his work in the area of Multiple Intelligences, which has been a career-long pursuit to understand and describe the construct of intelligence (Gardner, 1999a; Project Zero Website, 2000). Gardner describes his work with two distinct populations as the inspiration for his theory of Multiple Intelligences. Early in his career, he began studying stroke victims suffering from aphasia at the Boston University Aphasia Research Center and working with children at Harvard's Project Zero, a laboratory designed to study the cognitive development of children and its associated educational implications (Gardner, 1999a). In Intelligence Reframed, Gardner states, Both of the populations I was working with were clueing me into the same message: that the human mind is better thought of as a series of relatively separate faculties, with only loose and unpredictable relations with one another, than as a single, all-purpose machine that performs steadily at a certain horsepower, independent of content and context. (p.32) Gardner concluded from his work with these two populations that strength in one area of performance did not reliably predict comparable strength in another area. With this intuitive conclusion in mind, Gardner set about studying intelligence in a systematic, multi-disciplinary, and scientific manner, drawing from psychology, biology, neurology, sociology, anthropology, and the arts and humanities. This resulted in the emergence of his Theory of Multiple Intelligences (MI Theory) as presented in Frames of Mind (1983). Since the publication of that work, Gardner and others have continued to research the theory and its implications for education in general, curriculum development, teaching, and assessment. For the purposes of this Hot Topic, the focus will be on a description of the theory, major criticisms, and the implications for assessment. Definition of MI Theory According to Gardner (1999a), intelligence is much more than IQ because a high IQ in the absence of productivity does not equate to intelligence. In his definition, "Intelligence is a bio- psychological potential to process information that can be activated in a cultural setting to solve problems or create products that are of value in a culture" (p.34). Consequently, instead of intelligence being a single entity described psychometrically with an IQ score, Gardner's definition views it as many things. He endeavoured to define intelligence in a much broader way than psychometricians. Gardner established several criteria to achieve this goal (1983; 1999a). In identifying capabilities to be considered for one of the "multiple intelligences" the construct under consideration had to meet several criteria rather than resting on the results of a narrow psychometric approach. To qualify as ”intelligence" the particular capacity under study was considered from multiple perspectives consisting of eight specific criteria drawn from the biological sciences, logical analysis, developmental psychology, experimental psychology, and psychometrics. The criteria to consider "candidate intelligences" (Gardner, 1999a, p. 36) are: 1) the potential for brain isolation by brain damage, 2) its place in evolutionary history, 3) the presence of core operations, 4) susceptibility to encoding, 5) a distinct developmental progression, 6) the existence of idiot-savants, prodigies and other exceptional people, 7) support from experimental psychology, and 8) support from psychometric findings (Gardner, 1999a). 18

- 19. To illustrate the specifics of these criteria, a brief description and example of each is provided. The potential for brain isolation by brain damage means that one "candidate intelligence" (Gardner 1999a, p.36) can be dissociated from others. This criterion came from Gardner's work in neuropsychology. For example, stroke patients who are left with some forms of "intelligence" intact despite damage to other cognitive abilities such as speech. From an evolutionary perspective, the candidate intelligence has to have played a role in the development of our species and its ability to cope with the environment. In this case, Gardner (1999a) uses inference to conclude that spatial abilities were critical to the survival of our species. Early hominids had to be able to navigate diverse terrains using spatial abilities. The pressure of the environment then resulted in selection for this ability. Both of these criteria emerged from the biological sciences. From the perspective of logical analysis, an intelligence must have an identifiable core set of operations. Acknowledging the fact that specific intelligences operate in the context of the environment, Gardner (1999a) argues that it is crucial to specify the capacities that are central to the intelligence under consideration. For example, linguistic intelligence consists of core operations such as recognition and discrimination of phonemes, command of syntax and acquisition of word meanings. In the area of musical intelligence, the core operations are pitch, rhythm, timbre, and harmony. Another criterion related to logical analysis states that an intelligence must be susceptible to encoding in a symbol system. According to Gardner, (1999a) symbol systems are developed versus occurring naturally, and their purpose is to accurately and systematically convey information that is culturally meaningful. Some examples of encoding include written and spoken language, mathematical systems, logical equations, maps, charts and drawings. Gardner (1999a) established two criteria from developmental psychology. The first is the presence of a developmental trajectory for the particular ability toward an expert end-state. In other words, individuals do not necessarily exhibit their "intelligence" in its raw state. Rather, they prepare to use their intelligence by passing through a developmental process. Thus, people who want to be mathematicians or physicists, spend years studying and honing their logical/mathematical abilities in a distinctive and socially relevant way. The second criteria borrowed from the discipline of developmental psychology, is the existence of idiot-savants, prodigies and exceptional people. Gardner (1999a) refers to these as accidents of nature that allow researchers to observe the nature of a particular intelligence in great contrast to other average or impaired abilities. One example of this type of highlighted intelligence is the autistic person who excels at numerical calculations or musical performance. Finally, Gardner (1999a) draws his last two criteria from traditional psychology and psychometrics to determine if candidate intelligence makes it onto the list of specific abilities he calls Multiple Intelligences. There must be support from experimental psychology that indicates the extent to which two operations are related or different. Observing subjects who are asked to carry out two activities simultaneously can help determine if those activities rely on the same mental capacities or different ones. For example, a person engaged in working a crossword puzzle is unlikely to be able to carry on a conversation effectively, because both tasks demand the attention of linguistic intelligence, which creates interference. Whereas, the absence of this sort of competition allows a person to be able to walk and converse at the same time suggesting that two different intelligences are engaged. In spite of the fact that Gardner proposed his theory in opposition to psychometrics, he recognizes the importance of acknowledging psychometric data (1999a). Gardner (1983; 1999a) defined seven intelligences using the preceding eight criteria. Logical- mathematical intelligence is the ability to detect patterns, think logically, reason deductively and carry out mathematical operations. Linguistic intelligence involves the mastery of spoken and written language to express oneself or remember things. These first two forms of intelligence are typically the abilities that contribute to strong performance in traditional school environments and to producing high scores on most IQ measures or tests of achievement. Spatial intelligence involves the potential for recognizing and manipulating the patterns of both wide spaces such as those negotiated by pilots or navigators, and confined spaces such as those encountered by sculptors, architects or championship chess players. Musical intelligence consists of the capacity to recognize and compose musical pitches, tones, rhythms, and patterns and to use them for performance or composition. Bodily- Kinaesthetic intelligence involves the use of parts of the body or the whole body to solve problems or 19

- 20. create products. Athletes, dancers, surgeons and craftspeople are likely to have highly developed capacity in this area. The last two intelligences are the personal intelligences: interpersonal and intrapersonal. Interpersonal intelligence indicates a person's ability to recognize the intentions, feelings and motivations of others. People who possess and develop this quality are likely to work well with others and may choose fields like sales, teaching, counselling or politics in order to use them. Intrapersonal intelligence is described as the ability to understand oneself and use that information to regulate one's own life. According to Gardner each of these seven "intelligences" has a specific set of abilities that can be observed and measured (1999a, 1983). More recently, Gardner (1998) has nominated three additional candidate intelligences: Naturalist, Spiritual and Existential intelligence and evaluated them in the context of the eight criteria he established in his research and outlined earlier in this paper. He defines a naturalist as a person "who demonstrates expertise in recognition and classification of the numerous species - the flora and fauna - of her or his environment." (1998, p. 115). Gardner is comfortable with declaring that a Naturalist intelligence meets the criteria he set forth, however he is less sure about how to define and incorporate Spiritual and Existential intelligences. "…the monopoly of those who believe in a single general intelligence has come to an end." (Gardner, 1999a, p.203) Criticism of MI Theory When reviewing criticism of Multiple Intelligences theory, addressing the historically ever-present question of whether intelligence is one thing or many things is unavoidable. The fundamental criticism of MI theory is the belief by scholars that each of the seven multiple intelligences is in fact a cognitive style rather than a stand-alone construct (Morgan, 1996). Morgan, (1996) refers to Gardner's approach of describing the nature of each intelligence with terms such as abilities, sensitivities, skills and abilities as evidence of the fact that the "theory" is really a matter of semantics rather than new thinking on multiple constructs of intelligence and resembles earlier work by factor theorists of intelligence like L.L. Thurstone who argued that a single factor (g) cannot explain the complexity of human intellectual activity. According to Morgan (1996), identifying these various abilities and developing a theory that supports the many factors of intelligence has been a significant contribution to the field. Furthermore, he believes that MI theory has proven beneficial to schools and teachers and it may help explain why students do not perform well on standardized tests but it in Morgan's opinion it does not warrant the complete rejection of g. Gardner (1995) admittedly avoided addressing criticism of his theory for nearly a decade after the publication of Frames of Mind. However, in a 1995 article that appeared in Phi Delta Kappan he responds to several "myths" about the Theory of Multiple Intelligences. These myths provide a summary of the major commentary on and criticism of Gardner's theory. The first myth is that if there are seven intelligences we must be able to measure them with seven specific tests. Gardner is vocal about his disdain for a singularly psychometric approach to measuring intelligence based on paper and pencil tests. Secondly, he responds to the belief that an intelligence is the same as a domain or a discipline. Gardner reiterates his definition of an intelligence and distinguishes it from a domain which he describes as a culturally relevant, organized set of activities characterized by a symbol system and a set of operations. For example, dance performance is a domain that relies on the use of bodily- kinaesthetic and musical intelligence (Gardner, 1995). Other criticisms include the notion that MI theory is not empirical, is incompatible with inheritability, and environmental influences, and broadens the construct of intelligence so widely as to render it meaningless. Gardner (1995) staunchly defends the empiricism of the theory by referring to the numerous laboratory and field data that contributed to its development and the ongoing re- conceptualization of the theory based on new scientific data. Regarding the claim that Multiple Intelligences theory cannot accommodate g, Gardner argues that g has a scientific place in intelligence theory but that he is interested in understanding intellectual processes that are not explained by g. In response to the criticism that MI theory is incompatible with genetic or environmental accounts of the nature of intelligence, Gardner states that his theory is most concerned with the interaction between genetics and the environment in understanding intelligence. Finally, the notion that MI theory has expanded the definition of intelligence beyond utility produces a strong reaction from Gardner. He argues passionately that the narrow definition of intelligence as equal to 20

- 21. scholastic performance is simply too constrictive. In his view, MI theory is about the intellectual and cognitive aspects of the human mind. Gardner is careful to point out that MI theory is not a theory of personality, morality, motivation, or any other psychological construct (1995, 1999a, 1999b). Implications for Assessment The two most widely used standardized tests of intelligence are the Wechsler scales and the Stanford-Binet. Both instruments are psychometrically sound, but Gardner believes that these tests measure only linguistic and logical/mathematical intelligences, with a narrow focus within content in those domains. According to Gardner, the current psychometric approach for measuring intelligence is not sufficient. In his view, assessment must cast a wider net to measure human cognitive abilities more accurately. Gardner (1993) proposes several improvements for the development of intelligence measures. Before enumerating those improvements, it is important to understand how Gardner defines assessment. In his view, the purpose of assessment should be to obtain information about the skills and potentials of individuals, and provide useful feedback to the individuals and the community at large. Furthermore, Gardner (1993) draws a distinction between testing and assessment. Assessment elicits information about an individual's abilities in the context of actual performance rather than by proxy using formal instruments in a de-contextualized setting. Gardner argues for making assessment a natural part of the learning environment. Assessment is then built into the learning situation much like the constant assessment of skills that occurs in apprenticeship or the self-assessment that occurs in experts who have internalized a standard of performance based on the earlier guidance of teachers. The ecological validity of assessment is also at issue according to Gardner (1993). Predictive validity of traditional intelligence tests may be psychometrically sound, but its usefulness beyond predicting school performance is questionable. Therefore, prediction could be improved if assessments more closely approximated real working conditions. Instruments for measuring intelligence should also be "intelligence-fair" (1993, p.176). Consequently, we need to reduce the bias toward measuring intelligence through logical/mathematical and linguistic abilities and move toward looking more directly at a specific intelligence in operation (e.g., assessing for spatial intelligence by having an individual navigate his or her way around unfamiliar territory). Gardner acknowledges that this approach to assessment may be difficult to implement. Gardner (1993) emphasizes two additional points about assessment that are critical. The first is that the assessment of intelligence should encompass multiple measures. Relying on a single IQ score from a WISC-III (Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children) without substantiating the findings through other data sources does the individual examinee a disservice and produces insufficient information for those who provide interventions. Secondly, all assessments and resulting interventions must be sensitive to individual differences and developmental levels. Finally, Gardner is in favour of assessment for the primary purpose of helping students rather than classifying or ranking them. While these views about assessment are intuitively sensible, Sternberg (1991) argues that the naturalistic approach is a "psychometric nightmare" (p. 266). Quantifying performance on these sorts of assessments is difficult, objectivity is questionable, and cultural bias is still a problem. Hard data is the scientific "gold standard" and psychometric soundness is a prerequisite. Therefore, Sternberg (1991) hesitates endorsing this approach to assessment on the basis that we would simply be replacing one flawed system of measurement with an approach that is equally problematic. Recent research on MI Theory-based assessments provides evidence in support of Sternberg's concern about psychometric quality (e.g., Plucker, Callahan, & Tomchin, 1996). Future Research Directions The future research agenda for MI Theory and intelligence is likely to encompass a multidisciplinary approach. While intelligence is usually researched through the lens of psychology, future discoveries are likely to come from the cross-pollination of ideas in neuroscience, cellular biology, genetics, and anthropology to name a few (1999a). Gardner (1999a) also favours gathering ethnographic data and cross-cultural information to see intelligence in action and in context. The use of information processing techniques and computer simulations is another relevant approach for gaining new insight 21

- 22. into human intellectual capacities. At this point in history, the study of intelligence has moved well beyond the realm of psychometrics. As Gardner (1999a) writes, "The theory of multiple intelligences has helped break the psychometricians’ century long stranglehold on the subject of intelligence." (p. 203) References Gardner, H. (1999a). Intelligence reframed: Multiple intelligences for the 21st century. New York: Basic Books. Gardner, H. (1999b, February). Who owns intelligence? Atlantic Monthly, 67-76. Gardner, H. (1998). Are there additional intelligences? The case for naturalist, spiritual, and existential intelligences In J. Kane (Ed.), Education, information, and transformation (pp. 111-131) Upper Saddle River, NJ: Merrill-Prentice Hall. Gardner, H. (1995). Reflections on multiple intelligences Phi Delta Kappan, 77(3), 200-208. Gardner, H. (1993). Multiple intelligences: The theory in practice. New York: Basic Books. Gardner, H. (1983). Frames of mind: The theory of multiple intelligences. New York: Basic Books. Morgan, H. (1996). An analysis of Gardner's theory of multiple intelligences Roeper Review 18, 263-270 Plucker, J., Callahan, C. M., & Tomchin, E. M. (1996) Wherefore art thou, multiple intelligences? Alternative assessments for identifying talent in ethnically diverse and economically disadvantaged students Gifted Child Quarterly, 40, 81-92 Sternberg, R. J. (1991). Death, taxes and bad intelligence tests Intelligence, 15, 257-269 http://www.pz.harvard.edu/PIs/HG.htm (2000). Biographical data on Howard Gardner Principle Investigators, Project Zero Website. http://www.nea.org/neatoday/9903/meet.html (1999). NEA Today Online, Meet Howard Gardner: All kinds of smarts. Prepared and submitted for the intelligence website by Lynn Gilman, M.S. Variations of Thinking Styles (Excerpts from Sternberg, 1997) The following are brief excerpts from the book "Thinking Styles" by Robert J. Sternberg. Readers are encouraged to read the book for detailed coverage of thinking styles, and of the "Theory of Mental Self-Government." PRINCIPLES OF THINKING STYLES Styles are preferences in the use of abilities, not abilities themselves. A match between styles and abilities creates synergy that is more than the sum of its parts. Life choices need to fit styles as well as abilities. People have profiles (or patterns) of styles, not just a single style. Styles are variable across tasks and situations. People differ in the strength of their preferences. 22

- 23. People differ in there stylistic flexibility. Styles are socialized. Styles can vary across the life span. Styles are measurable. Styles are teachable. Styles valued at one time may not be valued at another. Styles valued in one place may not be valued in another. Styles, on average, are not good or bad -- it's a question of fit. We confuse stylistic fit with levels of ability. FUNCTIONS OF THINKING STYLES Legislative Style Legislative people like to do things their own way. They like creating, formulating, and having things. In general, they tend to be people who like to make their own rules. Legislative people enjoy doing things the way they do them. They prefer problems that are not restructured for them, but rather that they can structure for themselves. Legislative people also prefer creative and constructive planning-based activities, such as writing papers, design projects, and creating new business or educational systems. Executive Style People with the executive style are implementers: they like to do, and generally prefer to be giving guidance as to what to do or how to do what needs to be done. Executive people also like to enforce rules and laws (their own or others'). Executive people prefer problems that are given to them or structured for them and like to do and take pride in the doers - in getting things done. Executive people tend to gravitate toward occupations that are quite different from those to which legislative people are attracted. Executive people will tend to the valued by organizations that want people to do things in a way that appears to a set of rules or guidelines. Judicial Style People with a judicial style like to evaluate rules and procedures and to judge things. Judicial people also prefer problems in which they can analyze and evaluate things and ideas. They like to judge both structure and content. Legislative and judicial people can work well together in a team. For example, selection procedures tend to be largely judicial, and are well suited to people who like to evaluate. The legislative person may well not be ideal to read the applications and judge them, for lack of interest in dealing with the job the way it should the done. FORMS OF THINKING STYLES Monarchic Style People who are predominantly monarchic style tend to be motivated by a single goal or need at a time. Monarchic people also tend to be single-minded and driven by whatever they are single-minded about. They have a tendency to see things in terms of their issues. Monarchic people often attempt to solve problems, full speed ahead, damn the obstacles. They can be too decisive. Hierarchic Style People with a hierarchic style tend to be motivated by a hierarchy of goals, with the recognition that not all of the goals can be fulfilled equally well and that some goals are more important than others. They thus tend to be priority setters who allocate carefully. They tend to be systematic and organized in their solutions to problems and in their decision making. 23

- 24. Oligarchic Style In oligarchy, several individuals share power. Individuals with the oligarchic style tend to be motivated by several, often competitive goals of equal perceived importance. They have trouble deciding which goals to give priority to. The result is that they may have trouble allocating resources. Anarchic Style People with an anarchic style tend to be motivated by a wide assortment of needs and goals that are often difficult for others, as well as for themselves, to sort out. They tend to be not so much asystematic as antisystematic. LEVELS, SCOPE, AND LEANINGS OF THINKING STYLES Global Style-Local Style Global people prefer to deal with relatively larger and often abstract issues. They tend to focus on the forest, sometimes at the expense of the trees. Their constant challenge is to stay grounded and not to get lost on cloud nine. Local people prefer to deal with details, sometimes minute ones, and often ones surrounding concrete issues. They tend to focus on the trees, sometimes at the expense of the forest. Their constant challenge is to see the whole forest, and not just its individual elements. Internal Style-External Style People with an internal style tend to be motivated, task-oriented, sometimes aloof, and socially less sensitive than other people. At times they also lack interpersonal awareness, if only because they do not focus on it. People with an external style, in contrast, tend to be more extroverted, people-oriented, outgoing, socially more sensitive, and interpersonally more aware. Liberal Style-Conservative Style Individuals with a liberal style like to go beyond existing rules and procedures and seek to maximize change. They also seek or are at least comfortable with ambiguous situations, and prefer some degree of unfamiliarity in life and work. Individuals with a conservative style like to adhere to existing rules and procedures, minimize change, avoid ambiguous situations where possible, and prefer familiarity in life and work. Matching Teaching Styles with Learning Styles in East Asian Contexts The Internet TESL Journal Vol. VII, No. 7, July 200 Rao Zhenhui rzhthm@public.nc.jx.cn Foreign Languages College, Jiangxi Normal University (Nanchang, China) Examples of Mismatches between Teaching and Learning Styles Liu Hong, a third-year English major in Jiangxi Normal University, China, was in David's office again. After failing David's oral English course the previous year, Liu Hong had reenrolled, hoping to pass it this year. Unfortunately, things were not looking promising so far, and she was frustrated. When David asked why she was so unhappy in his class, she said: “I am an introverted, analytic and reflective student. I don't know how to cope with your extroverted, global and impulsive teaching style?" 24

- 25. Jenny, an American teacher from California, sat in Dean's office again, feeling perplexed by the students' negative responses to her kinaesthetic and global styles of teaching. Despite Jenny's persistent efforts to convince the students of the advantages of her teaching styles, she was told by her Vietnamese colleagues that her attempts were in opposition to the prevalent teaching styles in Vietnam. Jenny had specialized in applied linguistics for a long time and was well trained in the TESOL area in U.S.A. But all of a sudden, it seemed that all her teaching competence and experience had become useless in such a country where she had never been before. Analyzing the Examples The above statements are representative of serious mismatches between the learning styles of students and the teaching style of the instructor. In a class where such a mismatch occurs, the students tend to be bored and inattentive, do poorly on tests, get discouraged about the course, and may conclude that they are not good at the subjects of the course and give up (Oxford et al, 1991). Instructors, confronted by low test grades, may become overtly critical of their students or begin to question their own competence as teachers, as exemplified by the Jenny's case above. To reduce teacher-student style conflicts, some researchers in the area of learning styles advocate teaching and learning styles be matched (e.g. Griggs & Dunn, 1984; Smith & Renzulli, 1984; Charkins et al, 1985), especially in foreign language instruction (e.g. Oxford et al, 1991; Wallace & Oxford, 1992). Kumaravadivelu (1991:98) states that: "... the narrower the gap is between teacher intention and learner interpretation, the greater are the chances of achieving desired learning outcomes". There are many indications (e.g. Van Lier, 1996; Breen, 1998) that bridging the gap between teachers' and learners' perceptions plays an important role in enabling students to maximize their classroom experience. Purpose of this Article This article describes ways to make this matching feasible in real-life classroom teaching in East Asian and comparable contexts. The assumption underlying the approach taken here is that the way we teach should be adapted to the way learners from a particular community learn. But before exploring how the teaching styles and learning styles can be matched, let us first examine traditional East Asian students' learning style preferences in dealing with language learning tasks. Traditional East Asian Learning Styles Traditionally, the teaching of EFL in most East Asian countries is dominated by a teacher-centered, book-centered, grammar-translation method and an emphasis on rote memory (Liu & Littlewood, 1997). These traditional language teaching approaches have resulted in a number of typical learning styles in East Asian countries, with introverted learning being one of them. In East Asia, most students see knowledge as something to be transmitted by the teacher rather than discovered by the learners. They, therefore, find it normal to engage in modes of learning which are teacher-centered and in which they receive knowledge rather than interpret it. According to Harshbarger el al (1986), Japanese and Korean students are often quiet, shy and reticent in language classrooms. They dislike public touch and overt displays of opinions or emotions, indicating a reserve that is the hallmark of introverts. Chinese students likewise name "listening to teacher "as their most frequent activity in senior school English classes (Liu & Littlewood, 1997). All these claims are confirmed by a study conducted by Sato (1982), in which she compared the participation of Asian students in the classroom interaction with that of non-Asian students. Sato found that the Asians took significant fewer speaking turns than did their non-Asian classmates (36.5% as opposed to 63.5%). The teacher-centered classroom teaching in East Asia also leads to a closure-oriented style for most East Asian students. These closure-oriented students dislike ambiguity, uncertainty or fuzziness. To avoid these, they will sometimes jump to hasty conclusions about grammar rules or reading themes. Many Asian students, according to Sue and Kirk (1972), are less autonomous, more dependent on authority figures and more obedient and conforming to rules and deadlines. Harshbarger at al (1986) noted that 25

- 26. Korean students insist that the teacher be the authority and are disturbed if this does not happen. Japanese students often want rapid and constant correction from the teacher and do not feel comfortable with multiple correct answers. That is why Asian students are reluctant to "stand out" by expressing their views or raising questions, particularly if this might be perceived as expressing public disagreement (Song, 1995). Perhaps the most popular East Asian learning styles originated from the traditional book-centered and grammar-translation method are analytic and field-independent. In most of reading classes, for instance, the students read new words aloud, imitating the teacher. The teacher explains the entire text sentence by sentence, analyzing many of the more difficult grammar structures, rhetoric, and style for the students, who listen, take notes, and answer questions. Oxford & Burry-Stock (1995) states that the Chinese, along with the Japanese, are often detail-and precision-oriented, showing some features of the analytic and field-independent styles. They have no trouble picking out significant detail from a welter of background items and prefer language learning strategies that involve dissecting and logically analyzing the given material, searching for contrasts, and finding cause-effect relationship. Another characteristically East Asian learning style is visual learning. In an investigation of sensory learning preferences, Reid (1987) found that Korean, Chinese and Japanese students are all visual learners, with Korean students ranking the strongest. They like to read and obtain a great deal of visual stimulation. For them, lectures, conversations, and oral directions without any visual backup are very confusing and can be anxiety-producing. It is obvious that such visual learning style stems from a traditional classroom teaching in East Asia, where most teachers emphasize learning through reading and tend to pour a great deal of information on the blackboard. Students, on the other hand, sit in rows facing the blackboard and the teacher. Any production of the target language by students is in choral reading or in closely controlled teacher-students interaction (Song, 1995). Thus, the perceptual channels are strongly visual (text and blackboard), with most auditory input closely tied to the written. Closely related to visual, concrete-sequential, analytic and field-independent styles are the thinking- oriented and reflective styles. According to Nelson (1995), Asian students are in general more overtly thinking-oriented than feeling oriented. They typically base judgement on logic and analysis rather than on feelings of others, the emotional climate and interpersonal values. Compared with American students, Japanese students, like most Asians, show greater reflection (Condon, 1984), as shown by the concern for precision and for not taking quick risk in conversation (Oxford et al, 1992). Quite typical is "the Japanese student who wants time to arrive at the correct answer and is uncomfortable when making guess" (Nelson, 1995:16). The Chinese students have also been identified to posses the same type of thinking orientation by Anderson (1993). The final East Asian preferred learning style is concrete-sequential. Students with such a learning style are likely to follow the teacher's guidelines to the letter, to be focused on the present, and demand full information. They prefer language learning materials and techniques that involve combinations of sound, movement, sight, and touch and that can be applied in a concrete, sequential, linear manner. Oxford & Burry-Stock (1995) discovered that Chinese and Japanese are concrete- sequential learners, who use a variety of strategies such as memorization, planning, analysis, sequenced repetition, detailed outlines and lists, structured review and a search for perfection. Many Korean students also like following rules (Harshbarger et al, 1986), and this might be a sign of a concrete-sequential style. It is worth noting that the generalizations made above about learning styles in East Asia do not apply to every representative of all East Asian countries; many individual exceptions of course exist. Nevertheless, these seemingly stereotypical descriptions do have a basis in scientific observation. Worthley (1987) noted that while diversity with any culture is the norm, research shows that individuals within a culture tend to have a common pattern of learning and perception when members of their culture are compared to members of another culture. Matching Teaching Styles with Learning Styles From the descriptions and scientifically observed data reviewed above, it is legitimate to conclude that there exist identifiable learning styles for most East Asian students. We can assume, therefore, that any native English speaker engaged in teaching English to East Asian students is likely to confront a teaching-learning style conflict. This is illustrated by the two examples cited at the very beginning of 26