BarrysHandouts

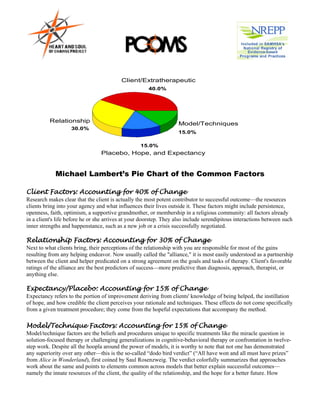

- 1. Client/Extratherapeutic 40.0% Relationship Model/Techniques 30.0% 15.0% 15.0% Placebo, Hope, and Expectancy Michael Lambert’s Pie Chart of the Common Factors Client Factors: Accounting for 40% of Change Research makes clear that the client is actually the most potent contributor to successful outcome—the resources clients bring into your agency and what influences their lives outside it. These factors might include persistence, openness, faith, optimism, a supportive grandmother, or membership in a religious community: all factors already in a client's life before he or she arrives at your doorstep. They also include serendipitous interactions between such inner strengths and happenstance, such as a new job or a crisis successfully negotiated. Relationship Factors: Accounting for 30% of Change Next to what clients bring, their perceptions of the relationship with you are responsible for most of the gains resulting from any helping endeavor. Now usually called the "alliance," it is most easily understood as a partnership between the client and helper predicated on a strong agreement on the goals and tasks of therapy. Client's favorable ratings of the alliance are the best predictors of success—more predictive than diagnosis, approach, therapist, or anything else. Expectancy/Placebo: Accounting for 15% of Change Expectancy refers to the portion of improvement deriving from clients' knowledge of being helped, the instillation of hope, and how credible the client perceives your rationale and techniques. These effects do not come specifically from a given treatment procedure; they come from the hopeful expectations that accompany the method. Model/Technique Factors: Accounting for 15% of Change Model/technique factors are the beliefs and procedures unique to specific treatments like the miracle question in solution-focused therapy or challenging generalizations in cognitive-behavioral therapy or confrontation in twelve- step work. Despite all the hoopla around the power of models, it is worthy to note that not one has demonstrated any superiority over any other—this is the so-called “dodo bird verdict” (“All have won and all must have prizes” from Alice in Wonderland), first coined by Saul Rosenzweig. The verdict colorfully summarizes that approaches work about the same and points to elements common across models that better explain successful outcomes— namely the innate resources of the client, the quality of the relationship, and the hope for a better future. How

- 2. Barry Duncan, Psy.D. 2 barrylduncan@comcast.net www.heartandsoulofchange.com 772.204.2511; 561.239.3640 exactly should models be viewed when so much of good clinical work is controlled by other factors—85% to be exact (40% client factors, 30% relationship factors, and 15% expectancy factors)? Read on. Empowering Client Factors 1. Listen for heroic stories. • The key here is the attitude you assume regarding your client’s inherent abilities—you must foster a determined mindfulness to find competencies, strengths, resiliencies, and resources that you know are there. TIPS • This does not mean that you must ignore pain Telling Heroic Stories: or assume a Pollyanna stance. Think of a time in your life that was very difficult, but • The stories of who we are have multiple sides, you managed to get through it. depending on who is recounting them and What personal resources did you draw on to get what sides are emphasized. Unfortunately, the Killer Ds (diagnosis, dysfunction, disorder, through this difficulty? disease, deficit) have persuaded us to believe What family, spiritual, friend, or community support in the story of pathology as the only or best version. It is neither. Many others of survival did you draw on to get through? and courage simultaneously exist—help your What does this story tell about who you are and what clients tell stories that portray their courage and heroism. you can do? Who else knows this story about you? • Bring three questions to your conversations: What are the obvious and hidden strengths, What do you think they say this story says about who resources, resiliencies, and competences you are and what you are capable of? contained in the client’s story? Who in your life wouldn’t be surprised to see you stand • What are the competing stories that can be up to the current problem and prevail? What told—the stories of clarity, coping, endurance, and desire that exist simultaneously with the experiences of you would they draw upon to make this stories of confusion, pain, suffering, and conclusion? What story would they tell about you? desperation? • What is already there to be recruited for change? 2. Develop a change-focus. • Listen for a change--whenever and for whatever reason it occurs. Ask about what, if any, changes clients have noticed since the time they scheduled their appointment. (monitor and measure change) Many people notice that, between the time they called for the appointment and the actual first session, things already seem different. What have you noticed about your situation? • Listen for key words that reflect change. When clients say: Thing have been really bad until recently; He is failing all of his classes except math; We are not screeching at each other anymore. Take notice and follow up. • Ask about change between sessions. 2

- 3. What is different since our last meeting? What is better? The ORS really helps here. 3. Validate the client's contribution to change. • When change happens, ask clients to elaborate the change and their contribution to it. What was happening at those times? What do you think you were doing to help that along? What would you need to do (or what would need to happen) to experience more of that? As you continue to do these good things for yourself (or take advantage of what is helping), what difference will that make tomorrow? How will your day go better? The day after? • Link the positive change to the client’s own behavior. Even if clients attribute change to luck, fate, you, or a medication they can still be asked: (1) how they adopted the change in their lives, (2) what they did to use the TIPS changes to their benefit, and (3) what they will do in the future to ensure their Other Strength-Based Questions: gains remain in place. Wait a second. You did what? Tell me 1. What are the traits, qualities, and characteristics that more. How did you know to do what describe you when you are at your very best? What were you you did? That was thoughtful. What is it about doing when these aspects became apparent to you? you that helped you to do what you 2. What kind of person do these aspects describe? did? What does it say about you that you 3. What are the traits, qualities, and characteristics that others took advantage of the medication at would describe in you when you are at your very best? What this time? What part of you was lying dormant, ready to come out that the were you doing when they noticed these aspects in you? medication gave a boost to? 4. What kind of person do these aspects describe? 5. Who was the first person to tell you that they noticed the best • Make before and after distinctions. Encourage the client to look at his or of you in action? What were you doing when they noticed her life before and after any changes these aspects? were made. The idea is to encourage client reflection and to distinguish 6. Who was the last person to tell you that they noticed the best between the way things were before the of you in action? What were you doing when they noticed change, and how things are now, after the change. This invites clients to these aspects? explore the significance of their actions 7. When I am at my very best, I am ___________________. and tell a different story about their lives—one of triumph, enlightenment, and tenacity.

- 4. Barry Duncan, Psy.D. 4 barrylduncan@comcast.net www.heartandsoulofchange.com 772.204.2511; 561.239.3640 4. Tap into the client’s world. Whether seeking out a trusted friend or family member, purchasing a book or tape, attending church or a mutual-help group, clients find support outside of your agency. • Listen for and then be curious about what happens in the client's life that is helpful. • Inquire about the helpful aspects of the client's social support network, activities that provide relief, even if temporary, and circumstances in which the client feels most capable, successful, and composed. • Identify not what clients need, but what they already have in their world that can be put to use in reaching their goals Whom does the client refer to as helpful in his or her day-to-day life? How or what does the client do to get these persons to help him or her? What persons, places, or things does the client seek out between sessions for even a small measure of comfort or aid? What persons, places, or things has the client sought out in the past that were useful? What was different about those times that enabled the client to use those resources? Empowering Alliance Factors 1. Think of the alliance as the overarching framework of doing therapy; it transcends any specific therapist behavior and is a property of all. 2. The function of the alliance is to engage the client in purposive work. 3. It’s hard work; have to earn it with each and every client. 4. Court the client's favor and woo their participation—fit their ideas of a good relationship Attitude Important Alliance is Central Filter Is what I am doing and saying now building or risking the alliance? Doesn’t mean you can’t challenge but rather that you have to earn the right and, consider the alliance consequences • Carefully monitor the client’s reaction to comments, explanations, interpretations, questions and suggestions. Use the client’s language—their words, ideas, and expressions. Stay close to their descriptions of their lives. (Monitor and measure the alliance.) • Be flexible. Some clients will prefer a formal or professional manner over a casual or warmer one. Others might prefer more self-disclosure from their therapist, greater directiveness, a focus on their symptoms or a focus on the possible meanings beneath them, a faster or perhaps, a more laid back pace for therapeutic work. The one-approach-fits-all strategy is guaranteed to undermine alliance formation. You are 4

- 5. multidimensional—you are already many things to many people (friend, partner, parent, child, sibling). Use your complexity to fit clients! (Monitor and measure the alliance.) • Validate the client. Validation occurs when client’s thoughts, feelings, and behaviors are accepted, believed, and considered completely understandable given trying circumstances. Legitimize the client’s concerns and highlight the importance of the client’s struggle. Validation combines empathy and positive regard. 5. Accept client goals at face value. • Work on client goals, period. Listen and then amplify the stories and experiences that clients offer about their problems, TIPS including their thoughts, feelings, and ideas about “where they want Validation requires you to accept your client at face value and to go and the best way to get search for justification of his or her experience—replacing the there.” (Monitor and measure the alliance.) invalidation that may be a part of it. Ask yourself the following questions about the client’s story: • Ask directly about the client’s goals. • What are the obvious and hidden invalidations contained in What is your goal for treatment? the client’s story? How is the client or others discounting or What did you (hope/wish/think) would be different because of contradicting his or her experiences? How is he or she or coming here? others blaming the client for this situation? What did you want to change about your (life/problem/etc.)? • What other factors or circumstances have contributed to What would have to be minimally this situation or are extenuating or mitigating variables? different to consider our work together a success? How can I place the client’s situation in a context that What will be the first sign to you explains and justifies his or her behavior or feelings? How that you have taken a solid step on the road to improvement even can I give the client credit for trying to do the right thing? though you might not yet be out • How is this experience representative of an important of the woods? crossroad in the client’s life or a statement about his or her 6. Form all plans and tasks with the identity? What message is the client’s internal wisdom client. • Fit the client’s theory of change attempting to express? (see below) (Monitor and • Put the client’s experience in the following format: measure the alliance.) No wonder you feel or behave this way (fill in with client • Technique and relationship are circumstance) given that (fill in the ways you have discovered to not disembodied parts. Have to justify his or her responses). have some treatment, some Finally: • Now that the client is validated, what different conclusions are reached? Did any other courses of action emerge?

- 6. Barry Duncan, Psy.D. 6 barrylduncan@comcast.net www.heartandsoulofchange.com 772.204.2511; 561.239.3640 explanation and ritual. Securing agreement with the “what we are doing here” part is crucial to the alliance. If the selected technique doesn’t engage the client, it is not pulling its weight in the alliance. • Change is done with rather than to the client (e.g., fill out a genogram, take this medication, go into trance). • In a good alliance, helpers and clients jointly work to construct interventions that are in accordance with clients’ preferred outcomes. In this light, interventions represent an instance of the alliance in action. They cannot be separated from the client’s goals or the relationship in which they occur. Empowering Expectancy Factors 1. Believe in the client, in yourself and your work, and in the probability of change. • Show your faith in the client and your trust in your services. Know that no matter how troubling the client’s situation is, it will change. • Show interest in the results of whatever technique you employ. The ORS is a big help here. It helps you and the client notice the beneficial effects of service and conveys TIPS hope for and expectation of Choose an approach by asking yourself these questions: improvement. • Does the particular strategy capitalize on client strengths, 2. Orient therapy toward a resources, and abilities? hopeful future. • Clients are best served by • Does the orientation/intervention use the client’s existing helping them believe in support network? possibilities—of change, of accomplishing or getting what • Does the method identify or build on the changes clients they want, of starting over, of experience while in therapy? succeeding or controlling their life. • Would the client describe the therapeutic interaction resulting from the adoption of the particular strategy or orientation as • Facilitate hope and positive expectations for change by empathic, respectful, and genuine? exploring the pessimistic • Does the orientation/technique identify, fit with, or build on the assumptions clients have about the future. Ask client’s goals for therapy? questions to assist clients in • Does the orientation or strategy fit with, support, or envisioning a better future: What will be different when complement the client’s world view and theory of change? (anxiety, drinking, feuding with others, etc.) is behind • Does the theory or intervention fit with the client’s expectations you? for therapy? What will be the smallest sign that it’s getting better? What will be the first sign? When you no longer spend so much time struggling with (______), what will you be doing more of or instead? Who will be the first person to notice that you have achieved a victory? What will that person notice different that will tell him or her that the victory is achieved? 6

- 7. Where do suppose you will be when you first noticed the changes? What will have taken place just before the changes that will have helped them to happen? What will happen later that will help maintain them? 3. Highlight the client’s sense of personal control. • People who believe they can influence or modify the course of life events cope better and adjust more successfully. Ask questions that presuppose client influence over events occurring in his/her life. It is impressive that you took that step on your own to let the depression know who’s boss. When did it occur to you that that was the right thing to do? Now that you have done this, what else will you do to keep the depression on a short leash? • Connect with or draw upon a previously successful experience of the client. This shines a spotlight on the client’s agency and enhances hope for a different future. Have you ever faced anything like this before? What happened? How did you do that? What were the steps you went through? Who did you involve? Can you do any of those things now? How to Learn the Client’s Theory • Make direct inquiries about the client’s goals and ideas TIPS about change: What did you (hope/wish/think) would be different as a result of coming here? What did you want to change about your • The client’s theory of change (life/problem/etc.)? unfolds from a conversation What would be minimally different in your life to consider our work together a success? structured by your curiosity about What do you think would be helpful? the client’s ideas, attitudes, and What ideas do you have about what needs to happen for improvement to occur? speculations about change. Many times people have a pretty good hunch about • Honoring the client’s theory occurs not only what is causing a problem, but also what will resolve it. Do you have a theory of how change is when you follow, encourage, and going to happen here? implement the client’s ideas for • Listen for or inquire about the client’s usual change or when you select a method of, or experience with, change: technique or procedure that fits How does change usually happen? What causes change to occur? clients’ beliefs about their What does the client do to initiate change? problem(s) and the change process. What do others do to initiate/facilitate change? What is the usual order of the change process? • As the client’s theory evolves, What events usually precede/occur during/follow after implement the client’s identified the change? solutions or seek an approach that both fits the client’s theory and provides possibilities for change.

- 8. Barry Duncan, Psy.D. 8 barrylduncan@comcast.net www.heartandsoulofchange.com 772.204.2511; 561.239.3640 • Discuss prior solutions as a way of learning the client’s theory of change: What have you tried to help the problem/situation so far? Did it help? How did it help? Why didn’t it help? Exploring solution attempts enables you to hear the client’s evaluation of previous attempts and their fit with what the client believes to be helpful. Inquiring about prior solutions, therefore, allows you to hear the client’s frank appraisal of how change can occur. • Find out what your role is in the change process: How does the client view your part in the change process? Clients want different things. Some want a sounding board, some want a confidant, some want to brainstorm and problem solve, some want advice, some want an expert to tell them what to do. Explore the client’s preferences about your role by asking: How do you see me fitting into what you would like to see happen? How can I be of most help to you now? What role do you see me playing in your endeavor to change this situation? Let me make sure I am getting this right. Are you looking for suggestions from me about that situation? The Evolution of the Common Factors Now that you have a handle on the common factors, let’s look at a more complex, but satisfying representation of their effects and relationship to each other based on meta-analytic research. Remember the old public service message that showed an egg and said, “This is your brain,” and then as the egg is broken and starts to fry, the voiceover says, “This is your brain on drugs.” Think of the following figure as the common factors on drugs, or Barry on hallucinogens thinking about the factors. Take a look at the common factors as I describe them in my book, On Becoming a Better Therapist. Client/Extratherapeutic Factors (87%) Feedback Effects 15-31% Alliance Effects Treatment Effects 38-54% 13% Model/Technique 8% Model/Technique Delivered: Therapist Effects Expectancy/Allegiance 46-69% Rationale/Ritual (General Effects) Duncan, B. (2010). On Becoming a 30-?% Better Therapist. Washington DC: APA. The pie chart view of the common factors incorrectly implies that the proportion of outcome attributable to each was static and could be added up to 100% of therapy effects. This suggested that the factors were discrete elements 8

- 9. and could be distilled into a treatment model, techniques created, and then administered or “done” to the client. Any such formulaic application across clients, however, merely leads to the creation of another model. Another related problem is that despite descriptions of the factors as acting in concert with one another, the “pie chart” illustration promotes them as independent entities. In truth, they are interdependent, fluid, dynamic, and dependent on who the players are and what their interactions are like. So take a look at my depiction of the factors above. The proportion of outcome attributable to treatment is represented with pale blue, and nested within client factors (yellow). Even a casual inspection shows the disproportionate influence this group exerts. Subtracting treatment effects—the proportion of variability attributable to therapy (13%)—from everything (mostly the client) that contributes to a therapeutic outcome (100%), 87% of results lie outside of treatment. If we blow up that 13%, the result is second circle above, the overlapping elements that comprise the 13% of variance attributable to treatment. To exemplify the various factors and their attending portions of the variance, the Treatment of Depression Collaborative Research Program (TDCRP) will be enlisted. The TDCRP randomly assigned 250 depressed participants to four different conditions: CBT, interpersonal therapy (IPT), antidepressants plus clinical management (IMI), and a pill placebo plus clinical management. The four conditions—including placebo—achieved similar results, although both IPT and IMI surpassed placebo on the recovery criterion. Therapist Effects. Therapist factors represent the amount of variance attributable not to the model wielded, but rather to whom the therapist is. Depending on the study, therapist effects range from 6-9% of the overall variance of change or 46-69% of the variance attributed to treatment. In the TDCRP, 8% of the variance in the outcomes within each treatment was due to therapists. Consider also that the clients of the top third most effective psychiatrists receiving sugar pills did better than the clients of the bottom third taking antidepressants. Recent studies have found that therapists who generally form better alliances also had better outcomes. Such findings suggest that the alliance may represent the best arena for influencing the therapist effects. The Alliance. The amount of variance attributed to the alliance ranges from 5% to 7% (yellow) or 38-54% of that attributed to treatment (pale blue). In the TDCRP, the alliance was predictive of success for all conditions. Mean alliance scores accounted for up to 21% of the variance, while treatment differences accounted for at 0% of outcome variance. Keep in mind that treatment accounts for, on average, 13% of the variance. The alliance in the TDCRP accounted for more of the variance by itself, illustrating how the percentages are not fixed and depend on the particular context of client, therapist, alliance, and treatment model. Model/Technique in Context: Allegiance and Placebo (Expectancy) Factors Models achieve their effects, in large part, if not completely through the activation of placebo, hope, and expectancy, combined with the therapist belief in (allegiance to) the treatment administered. In fact, when a placebo or technically “inert” condition is offered in a manner that fosters positive expectations for improvement, it reliably produces effects almost as large as a bona fide treatment. Model/technique factors are the beliefs and procedures unique to specific treatments. As Jerome Frank seminally noted, they all include a rationale, offer a novel explanation for the client’s difficulties, and establish strategies to follow for resolving them. All models can be understood as healing rituals—technically inert, but nonetheless powerful, LINKS organized methods for enhancing the effects of client • www.heartandsoulofchange.com expectations for change. It pays, therefore, to have several • The Heart and Soul of Change rationales and remedies at your disposal that you believe in. The TDCRP is again instructive. While model accounted for (Duncan et al., 2010, APA) negligible variance, placebo factors loomed large. On the Beck • On Becoming a Better Therapist Depression Inventory, the placebo plus clinical management (Duncan, 2010, APA)

- 10. Barry Duncan, Psy.D. 10 barrylduncan@comcast.net www.heartandsoulofchange.com 772.204.2511; 561.239.3640 condition accounted for nearly 93% of the average response to the active treatment conditions. Feedback. The measurement of change, from the client’s perspective, has catapulted to the forefront of research and practice—and for good reason: monitoring client-based outcome, when combined with feedback to the clinician, significantly increases effectiveness. Our recent study in Norway found that feedback substantially increased positive outcomes. Feedback clients reached clinically significant change nearly four times more than non-feedback couples. The feedback condition maintained its advantage at 6 month follow-up and achieved nearly a 50% less separation/divorce rate. Based on a growing body of compelling empirical findings, feedback seems to improve outcomes across client populations and professional discipline, regardless of the model practiced—feedback is a vehicle to modify any delivered treatment for client benefit. Given its apparent broad applicability and lack of theoretical baggage, feedback can be argued to be a factor that demonstrably contributes to outcome regardless of the theoretical predilection of the clinician. It therefore could be considered a common factor of change. An inspection of the above figure reveals feedback to overlap with and affect all the factors—it is the tie that binds them together—allowing the other common factors to be delivered one client at a time. Soliciting systematic feedback is a living, ongoing process that engages clients in the collaborative monitoring of outcome, heightens hope for improvement, fits client preferences, maximizes therapist-client fit, and is itself a core feature of therapeutic change. Common factors research provides clues and general guidance for enhancing those elements shown to be most influential in positive outcomes. The specifics, however, can only be derived from the client’s response to any treatment delivered—the client’s feedback regarding progress in therapy and the quality of the alliance. Feedback enables a reliable and valid method of tailoring services to the individual; therapists need not know what approach should be used with each disorder, but rather whether the delivered approach is a good fit for and benefiting the client in-the moment. As such, feedback assumes a role alongside the more widely researched client, therapist, and alliance variables, emerging as a potential common factor. Why Partner with Clients? The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly of Therapeutic Services –and the REAL GOOD The Good: The good news is that the efficacy of psychotherapy is very good—the average treated person is better off than about 80% of the untreated sample, translating to an effect size (ES) of about 0.8. Moreover, these substantial benefits apparently extend from the laboratory to everyday practice. In short, there is a lot to feel proud about our profession: psychotherapy works. The Bad: The bad news is two-fold: First, drop outs are a significant problem in the delivery of mental health and substance abuse services, averaging at least 47%. When drops outs are considered, a hard rain falls on psychotherapy’s efficacy parade, both in randomized clinical trials (RCT) and in clinical settings. Second, despite the fact that the general efficacy is consistently good, not everyone benefits. Hansen, Lambert, and Foreman (2002), using a national data base of over 6000 clients, reported a sobering picture of routine clinical care in which only 20% of clients improved as compared to the 57-67% rates typical of RCTs. Whichever rate is accepted as more representative of actual practice, the fact remains that a substantial portion of clients go home without help. And the Ugly: Explaining part of the volatile results, variability among therapists is the rule rather than the exception. Not surprisingly, although rarely discussed, some therapists are much better at securing positive results than others. In fact, therapist effectiveness ranges from 20-70%! Moreover, even very effective clinicians seem to be poor at identifying deteriorating clients. Hannan et al. (2005) compared therapist predictions of client deterioration to 10

- 11. actuarial methods. Though therapists were aware of the study's purpose, familiar with the outcome measure used, and informed that the base rate was likely to be 8%, they accurately predicted deterioration in only one out of 550 cases; psychotherapists did not identify 39 out of the 40 clients who deteriorated. In contrast, the actuarial method correctly predicted 36 of the 40. So despite the overall efficacy and effectiveness of psychotherapy, drop outs are a substantial problem, many clients do not benefit, therapists vary significantly in effectiveness, and are poor judges of client deterioration. And the REAL GOOD: Feedback to the Rescue Real time feedback about the outcome of services dramatically increases effectiveness. Although helpers range from about 20 to 70% in their success with clients, effectiveness rates increase dramatically with feedback. No one is effective with everyone—even the best among us are not successful with almost a third of our clients. Finding this out early rather than late prevents ongoing ineffective work and encourages better options for the client. Continuous client feedback individualizes services based on client response, provides an early warning system that identifies at risk clients thereby preventing drop-outs and negative outcomes, and suggests a tried and true solution to the problem of provider variability—namely that feedback necessarily improves performance. The Partners for Change Outcome Management System (PCOMS) Devoted to empirically-derived clinical practices, PCOMS incorporates the most robust predictors of therapeutic success into an outcome management system that partners with clients while honoring the daily pressures of front- line clinicians. Unlike other methods of measuring outcome, this system truly gives clients the voice they deserve and assigns consumers key roles in determining how services are both delivered and funded. PCOMS uses two brief scales, the Outcome Rating Scale (ORS) and the Session Rating Scale (SRS) to measure the client's perspective benefit and the alliance, respectively. It is the only system that includes a transparent discussion of the results with clients and the only system to include routine measurement of the therapeutic alliance. PCOMS has been shown in 3 randomized clinical trials, all conducted by researchers at the Heart and Soul of Change Project, to significantly improve effectiveness in real clinical settings. PCOMS is recognized in SAMHSA’s National Registry of Evidence-based Programs and Practices. PCOMS has been implemented by hundreds of organizations, public and private, by thousands of behavioral healthcare professionals in all 50 states and 20 countries serving over 100,000 clients a year. Clinical Nuts and Bolts In the first contact, you want to: 1. Convey commitment toward improving client’s situation 2. Convey commitment to the highest quality of care 3. Begin partnering process—build a culture of feedback Ex. We are very concerned about whether you reach your goals at our agency. For this reason, it is very important that you are involved in monitoring our progress. We will make all the decisions regarding your situation together. I monitor my effectiveness with every client through the use of brief forms. These take only a couple minutes to fill out but yield a great deal of information about how things are going. I will give you one in the beginning of the session and one toward the end. This will allow us to monitor your change and my effectiveness throughout the course of our work together. I will explain this in greater detail when you arrive for your first session. If you would, please arrive 15 minutes early for your first session. This will give us time to fill out our intake forms without using any of our session time. Shall we schedule your appointment? Great!

- 12. Barry Duncan, Psy.D. 12 barrylduncan@comcast.net www.heartandsoulofchange.com 772.204.2511; 561.239.3640 Initial Session: Step 1: Introducing the ORS Ex. During the course of our work together, we will be giving you very short forms asking you how you think things are going and whether you think things are on track. We believe that to make the most of our time together and get the best outcome, it is important to make sure we are on the same page with one another about how you are doing, how we are doing, and where we are going. We will be using your answers to keep us on track. Will that be okay with you? Ex. Before we start I will greatly appreciate it if you would fill out the following form for me. The lines on this form measure the extent to which different life challenges may be impacting you at this time. Your answers would help me get a picture of the struggles that you may be facing at this time. While filling out this form keep in mind the events that have occurred in your life within the last week to the present time and the experiences you have had during that time. Ex. I’d like to introduce you to something I like to do when working with clients. This is called the ORS. Did our intake person mention it to you? Good! Let me just take a moment to provide you with a little more information about it. The ORS is an outcome measure that allows me to track where you’re at, how you’re doing, how things are changing or if they are not. It allows us to determine whether I am being helpful. That is very important to me. In a way this is monitoring both of us. I use this because I want to ensure that I am providing you with the best services possible. It only takes a minute to fill out and most clients find it to be very helpful. Would you like to give it a try? Great! Step 2: Incorporating the ORS The idea here is simple. The ORS provides an anchor of where the client is and allows a comparison point for later meetings. It involves the client in a joint effort to observe progress toward goals. The most neglected nuance of using the ORS is connecting the client’s mark on the lowest scale to his or her described experience and reason for service. Ex. From your ORS, it looks like you’re experiencing some real problems, or, From your scores, it looks like you’re feeling okay; what brings you here today? Or, if you like numbers more, Your total score is 15—wow, that’s pretty low. A score of 24 or lower indicates people who are in enough distress to seek help. Things must be pretty tough for you. Ex. The way this ORS works is that marks toward the left indicate that things are hard for you now or you are hurting enough to bring you to therapy. Your score indicates that you are really having a hard time. Would you like to tell me about it? Or if all the marks are to the right, Generally ,when most people make their marks so far to the right, it is an indication that things are going well for them. It would be really helpful for me to get an understanding of what it is that brought you to therapy at this point in time? Ex. And/or at some point in the meeting, you pick up on the client’s comments and connect them to the ORS: Oh, okay, sounds like dealing with the loss of your brother is an important part of what we are doing here. Is the distress from that situation account for your mark here on the ORS? Okay, so what do you think will need to happen for that mark to move toward the right? Your interest in the client’s desired outcome speaks volumes to the client about your commitment to them and the quality of service they receive. Step 3: Introducing the SRS Ex. During the session, we will take a short break in which I will give you another form that gives your opinion of our work together and if I am meeting your expectations. This information helps me stay on track. The ultimate purpose of using these forms is to make every possible effort to make coming to see me a beneficial experience for you. I need your help in making sure that I stay on the same page with you. Would that be okay with you? Ex. Before we wrap up tonight I would like you to fill out another short questionnaire. This one deals directly with how I am doing. It is very important to me that I am meeting your needs. A lot of research has shown that how well we work together directly relates to how well things go. If you could take a moment to fill it out, I will discuss it with you before you leave. Great, thanks 12

- 13. Step 4: Incorporating the SRS At the end of the session during the final message or summary process, incorporate the SRS responses. The SRS is easily scored by measuring the client’s marks on the line in a similar fashion as the ORS. Each line is 10 centimeters long. Just pick up on an item or two on the SRS and make comment on it. If there are any scores lower than 9 centimeters, follow up on it. Generally speaking, a total score of 36 or less should be discussed. The best thing that the SRS can do for you is to allow you to fix any alliance problems that are developing. The SRS shows clients that you do more than talk the talk—you are REALLY interested in their feedback and want to know what they think. Ex. Let me just take a second here to look at this SRS—it kind of like a thermometer that takes the temperature of our meeting here today. Wow, great, it looks good, looks like we are on the same page, that we are talking about what you think is important and you believe today’s meeting was right for you. Ex. Let me quickly look at this other form here that let’s me know how you think we are doing. Okay, seems like I am missing the boat here. Was there something else I should have asked you about or should have done to make this meeting work better for you? What was missing here? Just bringing up any problems and your willingness to be flexible and nondefensive speaks reams to the client and usually turns things around quickly. This process is repeated in every session. Follow up Sessions: Checking for Change Okay, you got the idea. Now it gets interesting. Here is where you get down to the business of being outcome- informed—the client’s view of progress really influences what you do. • Greet clients and provide them with the ORS to complete. You may also have a folder with blank forms available in your waiting room. • Compare this session’s ORS with the previous one and look for any changes. • Is there an improvement (a move to the right), a slide (a move to the left), or no change of any kind? Is there an increase in the total score of at least 5, or an increase to a total of 25 or more? Is there a decrease or no change at all? • Present the change or absence of change and engage the client in a discussion about their marks or scores. Ex. Holy cow! Wow, your mark on the personal well-being line really moved—about 3 centimeters to the right! What happened? How did you pull that off?…This kind of change is called a reliable change and may mean that it’s time for us to reevaluate. Where do you think we should go from here? Or, Look, your total increased by 8 points to 29 points. That’s quite a jump! Refer above to eliciting change talk about asking questions about the noted changes. Ex. Okay, so things haven’t changed since the last time we talked. How do you make sense of that? Should we be doing something different here or should we continue on course steady as we go? Again the idea is that the client is involved in the process of monitoring progress and the decision about what to do next. Implementing process and outcome measures gives helpers, consumers, and third party payers a different and reliable way to maximize time, effort, and results. For a complete clinically nuanced discussion of the use of the measures replete with examples, check out On Becoming a Better Therapist. Working with Kids and Families: Using the CORS and CSRS Use the child measures in a similar fashion to the adult measures. There are some differences: • When the child is presented as the problem, use the CORS with the child and parents; do not obtain ORS scores of the parents unless they identify separate problems for themselves.

- 14. Barry Duncan, Psy.D. 14 barrylduncan@comcast.net www.heartandsoulofchange.com 772.204.2511; 561.239.3640 • The measures encourage conversations about similarities and differences; and they allow therapists to attend to each person’s perspective of both change and the alliance. They provide a common ground on which to make comparisons and draw distinctions, allowing each individual to be part of the discussion of what needs to happen next. • It is not unusual for families to hold different perspectives. Using a graph with different-colored lines for each person helps illustrate varying viewpoints and can open up a productive conversation. • The CSRS and SRS give therapists a chance to see which, if any, family members are feeling the least connected to the process. The therapist then has accurate knowledge of where to focus more attention. Using the CORS and ORS with families is an invaluable way to keep track of many change trajectories and many agendas—all it takes is a willingness on the therapist’s part to become adept at seamless data gathering for several people in session and the ability to make that information meaningful by using it as a springboard for conversation. The reward is the same, whether child or family—reliable feedback about whether things are changing and the strength of the alliance, so counseling can better fit client preferences for the best outcome. About the Heart and Soul of Change Project The Heart and Soul of Change Project (hereafter the Project) is a practice-driven, training and research initiative that focuses on what works in therapy, and more importantly, how to deliver it on the front lines via client based outcome feedback, or what is called PCOMS. The Project features an international community of providers of all stripes and flavors as well as researchers and professors, all dedicated to privileging consumers and improving psychotherapy and substance abuse outcomes. Researchers at the Project conducted all three RCTs that led to the designation of PCOMS as a evidence based practice in SAMHSA’s National Registry of Evidence-based Programs and Practices. In addition to the RCTs addressing PCOMS and the benefits of consumer feedback, researchers and scholars at the Project have published 15 other studies and papers regarding improving psychotherapy outcomes and the training of mental health and substance abuse professionals. The Project is distinguished by its commitment to ongoing research and dissemination to front line practitioners. About the Director, Barry Duncan, Psy.D. Barry L. Duncan, Psy.D., is a therapist, trainer, and researcher with over 17,000 hours of clinical experience. Dr. Duncan has over one hundred publications, including fifteen books addressing systematic client feedback, consumer rights and involvement, the power of relationship, and a risk/benefit analysis of psychotropic medications. His work regarding consumer rights and client feedback has been implemented across the US and in 20 countries including national implementation in couple and family centers in Norway. His latest books: the 2nd edition of the Heart and Soul of Change (APA, 2010); and On Becoming a Better Therapist (APA, 2010). Because of his self help books, he has appeared on "Oprah," "The View," and several other national TV programs. Barry co- developed the ORS/SRS family of measures and PCOMS to give clients the voice they deserve as well as provide clients, clinicians, administrators, and payers with feedback about the client's response to services, thus enabling more effective care tailored to client preferences. He is the developer of the clinical process of using the measures and PCOMS, first articulated in the first edition of Heroic Clients, Client Agencies (Duncan & Sparks, 2002). Barry implements PCOMS in small and large systems of care and conducts agency trainings, workshops, and keynote presentations on all of the topics listed above for both professional and general audiences. Drawing upon his extensive clinical experience and passion for the work, Barry's trainings speak directly to the front line clinician. His presentations not only cover consumer based outcome feedback or PCOMS—which improves outcomes more than anything since the beginning of psychotherapy—Barry also talks about what it means to be a therapist and how each of us can re-remember and achieve our original aspirations to make a difference in the lives of those we serve. His trainings integrate the nuances of the work, our dependence on the resources of clients, and an appreciation of the hard work required for strong alliances across clients with the systematic use of outcome and alliance feedback. Video examples from a wide variety of clients demonstrate both the ideas and practices of CDOI and PCOMS—and moreover show that Barry doesn't just talk the talk. 14

- 15. Companion Books and a Video For For For Clients Schools Agencies