Renaissancefile

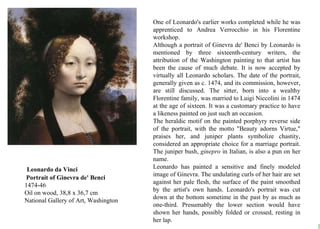

- 1. One of Leonardo's earlier works completed while he was apprenticed to Andrea Verrocchio in his Florentine workshop. Although a portrait of Ginevra de' Benci by Leonardo is mentioned by three sixteenth-century writers, the attribution of the Washington painting to that artist has been the cause of much debate. It is now accepted by virtually all Leonardo scholars. The date of the portrait, generally given as c. 1474, and its commission, however, are still discussed. The sitter, born into a wealthy Florentine family, was married to Luigi Niccolini in 1474 at the age of sixteen. It was a customary practice to have a likeness painted on just such an occasion. The heraldic motif on the painted porphyry reverse side of the portrait, with the motto "Beauty adorns Virtue," praises her, and juniper plants symbolize chastity, considered an appropriate choice for a marriage portrait. The juniper bush, ginepro in Italian, is also a pun on her name. Leonardo has painted a sensitive and finely modeled image of Ginevra. The undulating curls of her hair are set against her pale flesh, the surface of the paint smoothed by the artist's own hands. Leonardo's portrait was cut down at the bottom sometime in the past by as much as one-third. Presumably the lower section would have shown her hands, possibly folded or crossed, resting in her lap. Leonardo da Vinci Portrait of Ginevra de' Benci 1474-46 Oil on wood, 38,8 x 36,7 cm National Gallery of Art, Washington

- 2. Virgin of the Rocks 1483-86 Oil on panel, 199 x 122 cm Musée du Louvre, Paris The Paris Virgin of the Rocks is the one which first adorned the altar in San Francesco Grande. It may have been given by Leonardo himself to King Louis XII of France, in gratitude for the settlement of the suit between the painters and those who commissioned the works, in dispute over the question of payment. The later London painting replaced this one. For the first time Leonardo could achieve in painting that intellectual program of fusion between human forms and nature which was slowly taking shape in his view of his art. Here there are no thrones or architectural structures to afford a spatial frame for the figures; instead there are the rocks of a grotto, reflected in limpid waters, decorated by leaves of various kinds from different plants while in the distance, as if emerging from a mist composed of very fine droplets and filtered by the golden sunlight, the peaks of those mountains we now know so well reappear. This same light reveals the gentle, mild features of the Madonna, the angel's smiling face, the plump, pink flesh of the two putti. For this work, too, Leonardo made numerous studies, and the figurative expression is slowly adapted to the program of depiction. In fact, the drawing of the face of the angel is, in the sketch, clearly feminine, with a fascination that has nothing ambiguous about it. In the painting, the sex is not defined, and the angel could easily be either a youth or a maiden

- 3. There are differing opinions amongst art researchers as to which episode from the Gospels is depicted in the Last Supper. Some consider it to portray the moment at which Jesus has announced the presence of a traitor and the apostles are all reacting with astonishment, others feel that it also represents the introduction of the celebration of the Eucharist by Jesus, who is pointing to the bread and wine with his hands. And yet others feel it depicts the moment when Judas, by reaching for the bread at the same moment as Jesus as related in the Gospel of St Luke (22:21), reveals himself to be the traitor. In the end, none of the interpretations is convincing. Leonardo's Last Supper is not a depiction of a simple or sequential action, but interweaves the individual events narrated in the Gospels, from the announcement of the presence of a traitor to the introduction of the Eucharist, to such an extent that the moment depicted is a meeting of the two events. As a result, the disciples' reactions relate both to the past and subsequent events. The Apostles from left to right: Bartholomew, James the Less, Andrew, Judas, Peter, John, Christ, Thomas, James the Greater, Philip, Matthew, Thaddeus, Simon. The Last Supper 1498 Mixed technique, 460 x 880 cm Convent of Santa Maria delle Grazie, Milan

- 4. The Last Supper, housed in the church and former Dominican monastery of Santa Maria delle Grazie, has had an almost unbelievable history of bad luck and neglect -- its near destruction in an American bombing raid in August 1943 was only the latest chapter in a series of misadventures, including, if one 19th-century source is to be believed, being whitewashed over by monks. Yet Leonardo da Vinci chose to work slowly and patiently in oil pigments instead of proceeding hastily on wet plaster according to the conventional fresco technique. Well-meant but disastrous attempts at restoration have done little to rectify the problem of the work's placement: it was executed on a wall unusually vulnerable to climatic dampness. Novelist Aldous Huxley (1894-1963) called it "the saddest work of art in the world." After years of restorers' patiently shifting from one square centimeter to another, Leonardo's famous masterpiece is free of the shroud of scaffolding -- and centuries of retouching, grime, and dust. Astonishing clarity and luminosity have been regained. Reservations are required to view the work; call several days ahead for weekday visits and several weeks in advance for a weekend visit. The reservations office is open 9 AM-6 PM weekdays and 9 AM-2 PM on Saturday. Viewings are in 15-minute slots.

- 6. Mona Lisa (La Gioconda) c. 1503-5 Oil on panel, 77 x 53 cm Musée du Louvre, Paris According to Vasari, this picture is a portrait of Mona or Monna (short for Madonna) Lisa, who was born in Florence in 1479 and in 1495 married the Marquese del Giocondo, a Florentine of some standing - hence the painting's other name, `La Gioconda'. This identification, however, has sometimes been questioned. Leonardo took the picture with him from Florence to Milan, and later to France. It must have been this portrait which was seen at Cloux, near Amboise, on 10 October 1517 by the Cardinal of Aragon and his secretary, Antonio de Beatis. There is a slight difficulty here, however, because Beatis says that the portrait had been painted at the wish of Giuliano de Medici. Historians have attempted to solve this problem by suggesting that Monna del Giocondo had been Giuliano's mistress. The painting was probably acquired by François I from Leonardo himself, or after his death from his executor Melzi. It is recorded as being at Fontainebleau by Vasari (1550), Lomazzo (1590), Peiresc, and Cassiano del Pozzo (1625). The latter relates that when the Duke of Buckingham came to the French court to seek the hand of Henrietta of France for Charles I, he made it known that the King was most anxious to own this painting; but the courtiers of Louis XIII prevented him from parting with the picture. It was put on exhibition in the Musée Napoléon in I8o4; before that, in 1800, Bonaparte had it in his room in the Tuileries.

- 7. From the beginning it was greatly admired and much copied, and it came to be considered the prototype of the Renaissance portrait. It became even more famous in 1911, when it was stolen from the Salle Carrée on 21 August 1911 by Vicenzo Perrugia, an Italian workman. In 1913 it was found in Florence, exhibited at the Uffizi, then in Rome and Milan, and brought back to Paris on 31 December in the same year. This figure of a woman, dressed in the Florentine fashion of her day and seated in a visionary, mountainous landscape, is a remarkable instance of Leonardo's sfumato technique of soft, smoky modeling. The Mona Lisa's enigmatic expression, which seems both alluring and aloof, has given the portrait universal fame. Reams have been written about this small masterpiece by Leonardo, and the gentle woman who is its subject has been adapted in turn as an aesthetic, philosophical and advertising symbol, entering eventually into the irreverent parodies of the Dada and Surrealist artists. Vasari relates that Leonardo worked on it for four years without being able to finish it; yet the picture gives the impression of being completely realized. The dates suggested for it vary between 1503 and 1513, the most widely accepted being 1503-05. Taking a living model as his point of departure, Leonardo has expressed in an ideal form the concept of balanced and integrated humanity. The smile stands for the movement of life, and the mystery of the soul. The misty blue mountains, towering above the plain and its river, symbolize the universe. There is a suggestion of a smile both in the Mona Lisa's eyes and on the lips and in the corners other mouth; it appears unfathomable and mysterious and during the course of the centuries has given rise to any number of interpretations. Giorgio Vasari, writing about the arts, provided an amusing explanation: Leonardo wanted to depict the lady in a happy mood and for that reason arranged for musicians and clowns to come to the portrait sittings. In the essay "On the perfect beauty of a woman'', by the 16th-century writer Firenzuola, we learn that the slight opening of the lips at the corners of the mouth was considered in that period a sign of elegance. Thus Mona Lisa has that slight smile which enters into the gentle, delicate atmosphere pervading the whole painting.

- 10. The sheet includes studies from a number of years. The note "book on water to Mr. Marcho Ant" refers to the anatomical expert Marcantonio della Torre, who died in Pisa in 1511 and with whom Leonardo carried out dissections of human bodies. This drawing of the fetus was the result of knowledge rather than direct observation of nature. Leonardo had examined the fetus of a cow and allowed his observations of the placenta to influence this drawing. Studies of embryos 1509-14 Black and red chalk, pen and ink wash on paper, 305 x 220 mm Royal Library, Windsor

- 11. Vitruvian Man 1492 Pen, ink, watercolour and metalpoint on paper, 343 x 245 mm Gallerie dell'Accademia, Venice The drawing, probably the most famous by Leonardo, is a study of the human proportions from Vitruvius's De Architectura.

- 13. Bramante's Tempietto is in the courtyard of San Pietro in Montorio, believed to be the site of St Peter's martyrdom. The architect clearly worked from a historical typology: individual architectural elements such as columns, entablature, and vault acknowledge a debt to classical structures. The resulting centralized building represented a new type of Christian architecture. Bramante built the Tempietto small in size, hence the title and with classical allusion. The Tempietto is very symmetrical . The only aspect that it is not like ancient memorials is the fact that there is a drum between the main body of the building and the hemisphere of the dome. The little temple with its stylobate rests on three steps which link it to the plan of the courtyard. Sixteen Doric columns which form a luminous enclosure, support the beams above which rises the body of the temple; and the upward movement is stressed by the exterior ribs of the dome (a subdued echo of Brunelleschi). For Bramante, the planning of the Tempietto must have represented the union of illusionistic painting and architecture he had spent his career perfecting. The building, too small on the inside to accommodate a congregation (only 15 feet in diameter), was conceived as a 'picture' to be looked at from outside, a 'marker', a symbol of Saint Peter's martyrdom Bramante Tempietto 1502

- 14. By 1506, St. Peter's Basilica, the main church at the Vatican, was too small and decrepit to impress anyone. Following the examples set by emperors and sultans, Pope Julius II decided to crown the old church with a dome. He hired Italian architect Donato Bramante to do the job. Bramante's vision for the Basilica was simple: a Greek cross with equal-sized arms around a central dome. He proposed a centralized building with a dome, a design that expressed the Renaissance ideal of beauty. On 18 Apr 1506 the first stone was laid at the base of a pillar; a temporary chancel had been provided and a large part of the apse and transept demolished, causing Bramante to be nicknamed the “Destructive Maestro”. Sometimes a young man came to watch the work. His name was Michelangelo. Julius II had commissioned him to his tomb, which was to be placed at the heart of the new basilica. Michelangelo admired Bramante’s plan but disapproved of his administration. Having at first been regarded as an intruder, he came to be hated by Bramante . Four crossing piers were set, but construction on the new church ceased with Bramante's death in 1514.

- 16. The panel (signed and dated: "RAPHAEL URBINAS MDIIII.") was commissioned by the Albizzini family for the chapel of St Joseph in the church of S. Francesco of the Minorities at Città di Castello. Critics believe the painting to be inspired by two compositions by Perugino: the celebrated Christ Delivering the Keys to St Peter from the fresco cycle in the Sistine Chapel and a panel containing the Marriage of the Virgin now in the Museum of Caën. By painting his name and the date, 1504, in the frieze of the temple in the distance, Raphael abandoned anonymity and confidently announced himself as the creator of the work. The main figures stand in the foreground: Joseph is solemnly placing the ring on the Virgin's finger, and holding the flowering staff, the symbol that he is the chosen one, in his left hand. His wooden staff has blossomed, while those of the other suitors have remained dry. Two of the suitors, disappointed, are breaking their staffs. The polygonal temple in the style of Bramante establishes and dominates the structure of this composition, determining the arrangement of the foreground group and of the other figures. In keeping with the perspective recession shown in the pavement and in the angles of the portico, the figures diminish proportionately in size. The temple in fact is the center of a radial system composed of the steps, portico, buttresses and drum, and extended by the pavement. In the doorway looking through the building and the arcade framing the sky on either side, there is the suggestion that the radiating system continues on the other side, away from the spectator. Raphael Spozalizio (The Engagement of Virgin Mary) 1504

- 18. School of Athens , Raphael http://www.newbanner.com/AboutPic/athena/raphael/nbi_ath4.html

- 19. The School of Athens is a depiction of philosophy. The scene takes place in classical times, as both the architecture and the garments indicate. Figures representing each subject that must be mastered in order to hold a true philosophic debate - astronomy, geometry, arithmetic, and solid geometry - are depicted in concrete form. The arbiters of this rule, the main figures, Plato and Aristotle, are shown in the center, engaged in such a dialogue. The School of Athens represents the truth acquired through reason. Raphael does not entrust his illustration to allegorical figures, as was customary in the 14th and 15th centuries. Rather, he groups the solemn figures of thinkers and philosophers together in a large, grandiose architectural framework. This framework is characterized by a high dome, a vault with coffered ceiling and pilasters. It is probably inspired by late Roman architecture or - as most critics believe - by Bramante's project for the new St Peter's which is itself a symbol of the synthesis of pagan and Christian philosophies. The figures who dominate the composition do not crowd the environment, nor are they suffocated by it. Rather, they underline the breadth and depth of the architectural structures. The protagonists - Plato, represented with a white beard (some people identify this solemn old man with Leonardo da Vinci) and Aristotle - are both characterized by a precise and meaningful pose. Raphael's descriptive capacity, in contrast to that visible in the allegories of earlier painters, is such that the figures do not pay homage to, or group around the symbols of knowledge; they do not form a parade. They move, act, teach, discuss and become excited. The painting celebrates classical thought, but it is also dedicated to the liberal arts, symbolized by the statues of Apollo and Minerva. Grammar, Arithmetic and Music are personified by figures located in the foreground, at left. Geometry and Astronomy are personified by the figures in the foreground, at right. Behind them stand characters representing Rhetoric and Dialectic. Some of the ancient philosophers bear the features of Raphael's contemporaries. Bramante is shown as Euclid (in the foreground, at right, leaning over a tablet and holding a compass). Leonardo is, as we said, probably shown as Plato. Francesco Maria Della Rovere appears once again near Bramante, dressed in white. Michelangelo, sitting on the stairs and leaning on a block of marble, is represented as Heraclitus. A close examination of the intonaco shows that Heraclitus was the last figure painted when the fresco was completed, in 1511.

- 20. Raphael The Triumph of Galatea 1511 Fresco, 295 x 225 cm Villa Farnesina, Rome The Sienese Banker, Agostini Chigi, played a very important role in the cultural and artistic activities which flourished around Julius II. His house was built on the outskirts of Rome in 1509-1510, and was designed as a model of luxury and elegance. He commissioned Baldassarre Peruzzi, Sebastiano Luciani (later called Sebastiano del Piombo) and Raphael to decorate it. All three painted frescoes based on classical mythology in Chigi's house (which was later acquired by the Farnese family and came to be known as "La Farnesina"). As subject Raphael chose a verse from a poem by the Florentine Angelo Poliziano which had also helped to inspire Botticelli's 'Birth of Venus'. These lines describe how the clumsy giant Polyphemus sings a love song to the fair sea-nymph Galatea and how she rides across the waves in a chariot drawn by two dolphins, laughing at his uncouth song, while the happy company of other sea-gods and nymphs is milling round her. Every figure seems to correspond to some other figure, every movement to answer a counter-movement. To start with the small boys with Cupid's bows and arrows who aim at the heart of the nymph: not only do those to right and left echo each other's movements, but the boy swimming beside the chariot corresponds to the one flying at the top of the picture. It is the same with the group of sea-gods which seems to be 'wheeling' round the nymph. But what is more admirable is that all these diverse movements are somehow reflected and taken up in the figure of Galatea herself. Her chariot had been driving from left to right with her veil blowing backwards, but, hearing the strange love song, she turns round and smiles, and all the lines in the picture, from the love-gods' arrows to the reins she holds, converge on her beautiful face in the very center of the picture. By these artistic means Raphael has achieved constant movement throughout the picture, without letting it become restless or unbalanced. It is for this supreme mastery of arranging his figures, this consummate skill in composition, that artists have admired Raphael ever since.

- 21. Michelangelo was influenced by the discovery of two Greek sculptures. One of these is a statue of the Greek god Apollo and is called the " Apollo Belvedere " because after it was discovered in Rome in 1490 Pope Julius II (when he became Pope) had it placed in the courtyard of the Belvedere, which was the summer palace of the popes. So it was discovered 8 years before Michelangelo began work on his Pieta (1498-99) . Apollo is of course the ancient Greek god of (among other things) light, truth, reason. This is a Roman copy after a Greek bronze that was made in the late 4th century BC and is, of course, of the more restrained Hellenic tradition in which the quiet face spoke of reason governing the passions . The other sculpture was the Laocoon who was discovered in Rome in 1506 and is of course an example of Hellenistic art . We know that Michelangelo saw this one for he was there when it was being dug out of the earth and that it influenced him profoundly. Because he saw for the first time in the Laocoon an ancient example of the kind of the kind of expressiveness --the use of body language-he wanted in his own work .

- 22. Michelangelo Pietà 1499 Marble, height 174 cm, width at the base 195 cm Basilica di San Pietro, Vatican 1. study of ancient sculpture (here he's drawing from the more restrained Hellenic tradition, as opposed to the more dramatic Hellenistic) 2. study of anatomy 3. the Neoplatonic idea that beauty + truth are closely connected: the contemplation of Beauty leads to revelation 4. he's added some of his own touches: He's played w/ proportion: Mary would be 7 feet tall if she stood Mary's head is "too small" for her body giving her great monumentality. He's introduced some ambiguity by putting bulging veins on Christ's dead body, hinting at vitality

- 23. In the Pietà, Michelangelo approached a subject which until then had been given form mostly north of the Alps, where the portrayal of pain had always been connected with the idea of redemption: it was called the "Vesperbild" and represented the seated Madonna holding Christ's body in her arms. But now the twenty-three year-old artist presents us with an image of the Madonna with Christ's body never attempted before. Her face is youthful, yet beyond time; her head leans only slightly over the lifeless body of her son lying in her lap. "The body of the dead Christ exhibits the very perfection of research in every muscle, vein, and nerve. No corpse could more completely resemble the dead than does this. There is a most exquisite expression in the countenance. The veins and pulses, moreover, are indicated with so much exactitude, that one cannot but marvel how the hand of the artist should in a short time have produced such a divine work." One must take these words of Vasari about the "divine beauty" of the work in the most literal sense, in order to understand the meaning of this composition. Michelangelo convinces both himself and us of the divine quality and the significance of these figures by means of earthly beauty, perfect by human standards and therefore divine. We are here face to face not only with pain as a condition of redemption, but rather with absolute beauty as one of its consequences.

- 25. David 1504 Marble, height 434 cm Galleria dell'Accademia, Florence In 1501 Michelangelo was commissioned to create the David by the Arte della Lana (Guild of Wool Merchant), who were responsible for the upkeep and the decoration of the Cathedral in Florence. For this purpose, he was given a block of marble which Agostino di Duccio had already attempted to fashion forty years previously, perhaps with the same subject in mind. Michelangelo breaks away from the traditional way of representing David. He does not present us with the winner, the giant's head at his feet and the powerful sword in his hand, but portrays the youth in the phase immediately preceding the battle: perhaps he has caught him just in the moment when he has heard that his people are hesitating, and he sees Goliath jeering and mocking them. The artist places him in the most perfect " contrapposto", as in the most beautiful Greek representations of heroes. The right-hand side of the statue is smooth and composed while the left-side, from the outstretched foot all the way up to the disheveled hair is openly active and dynamic. The muscles and the tendons are developed only to the point where they can still be interpreted as the perfect instrument for a strong will, and not to the point of becoming individual self-governing forms. Once the statue was completed, a committee of the highest ranking citizens and artists decided that it must be placed in the main square of the town, in front of the Palazzo Vecchio, the Town Hall. It was the first time since antiquity that a large statue of a nude was to be exhibited in a public place. This was only allowed thanks to the action of two forces, which by a fortunate chance complemented each other: the force of an artist able to create, for a political community, the symbol of its highest political ideals, and, on the other hand, that of a community, which understood the power of this symbol. "Strength" and "Wrath" were the two most important virtues, characteristic of the ancient patron of the city Hercules. Both these qualities, passionate strength and wrath, were embodied in the statue of David.

- 27. When, by the will of Pope Julius della Rovere (1503-13), Michelangelo went to Rome in 1505, the Pope commissioned him to build in the course of five years a tomb for the Pope. Forty life-sized statues were to surround the tomb which was to be 7 meter wide, 11 meter deep and 8 meter high; it was to be a free-standing tomb and to contain an oval funerary cell. Never, since classical times, had anything like this, in the West, been built for one man alone. According to the iconographic plan, which we are able to reconstruct from written sources, this was to be an outline of the Christian world: the lower level was dedicated to man, the middle level to the prophets and saints, and the top level to the surpassing of both former levels in the Last Judgment. At the summit of the monument, there was to have been a portrayal of two angels leading the Pope out of his tomb on the day of the Last Judgment. Michelangelo immediately began his preparations for this task, but the capricious Pope, in doubt of finding an appropriate place in which to erect his tomb, planned something even more grandiose: the restoration and remodeling of St Peter's. Thus Michelangelo was ordered to make other commissions, first in Bologna then in Rome, the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel. After the death of the Pope in 1513 Michelangelo and the Pope's heirs reached a new agreement concerning the tomb. It was decided that the tomb was to be smaller and placed against a wall. After several further changes and simplifications the tomb was finally set up in San Pietro in Vincoli in Rome in 1545. The slaves (four in Florence and two in Paris) were intended to the lower level, while the Moses for the middle level

- 28. The statue of Moses is the summary of the entire monument, planned but never fully realized as the tomb of Julius II. It was intended for one of the six colossal figures that crowned the tomb. Elder brother to the Sistine Prophets, the Moses is also an image of Michelangelo's own aspirations, a figure in de Tolnay's words, "trembling with indignation, having mastered the explosion of his wrath". The Moses was executed for Michelangelo's second project for the tomb of Julius II. Inspired perhaps by the medieval conception of man as microcosm, he brought together the elements in allegorical guise: the flowing beard suggests water, the wildly twisting hair fire, the heavy drape earth. In an ideal sense, the Moses represents also both the artist and the Pope, two personalities who had in common what is known as "terribilità". Conceived for the second tier of the tomb, the statue was meant to be seen from below and not as it is displayed today at eye-level. Moses 1515 Marble, height 235 cm S. Pietro in Vincoli, Rome

- 29. The slaves (four in Florence and two in Paris) were intended to be at the lower level of the tomb of Pope Julius II, while the Moses for the middle level. From the realized version of the tomb, erected in the church San Pietro in Vincoli in Rome after several redesign and reduction of the original plan, the slaves were left out. The tomb of Julius II and the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel illustrate the triumph of the soul over the material world. Both the tomb and the Sistine chapel can be interpreted within a Neoplatonic scheme, but in these works, Neoplatonism operates in conjunction with Christian ideology. The struggle of the soul to free itself from matter is equated with the Christian doctrine of resurrection and eternal life. Tombs of popes were traditionally in three levels, which symbolized earthly existence, death and salvation (Fleming 189). Michelangelo's original plan for the tomb incorporated these divisions into a Neoplatonic representation of the soul's reunion with God. The lowest level included several slaves who were struggling to free themselves from their bonds. These statues represented souls who were enslaved in matter. The low state of the slaves was further emphasized by the appearance of the face of an ape in the marble around the Dying Slave . The ape was a "symbol of everything sub-human in man, of lust, greed, and gluttony" (Panofsky 195). Ficino and the Neoplatonists argued that the lower soul was "that nature which we have in common with the all animals" (Cassirer 196). In Christian terms, the slaves represented the soul in bondage to the passions. Bound slaves had long been used as a symbol of the "unresurrected human soul held in bondage by its natural desires" (Panofsky 194). The slaves were contrasted with the Victories, who "represent the human soul in its state of freedom, capable of conquering the base emotions by reason" (Panofsky 197). The lower level of the tomb, in both the Christian and Neoplatonic frameworks, represents the soul in its least desirable state.

- 30. Tomb of Giuliano de' Medici 1526-33 Marble, 630 x 420 cm Sagrestia Nuova, San Lorenzo, Florence Michelangelo received the commission for the Medici Chapel in 1520 from the Medici Pope Leo X (1513-23). The Pope wanted to combine the tombs of his younger brother Giuliano, Duke of Nemours, and his nephew Lorenzo, Duke of Urbino, with those of the "Magnifici", Lorenzo and his brother Giuliano, who had been murdered in 1478; their tombs were then in the Old Sacristy of San Lorenzo. The plans for the chapel which we still have, shows us that the Pope allowed Michelangelo a great freedom in his task. Not much of this vast plan was in fact carried out, yet it is enough to give us an idea of what Michelangelo's overall conception must have been. Each of the Dukes' tombs is divided into two areas, and the border is well marked by a projecting cornice. In the lower part are the sarcophagi with the mortal remains of the Dukes, on which lie Twilight and Dawn, Night and Day as the symbol of the vanity of things. Above this temporal area, the nobility of the figures of the Dukes and the subtlety of the richly decorated architecture which surrounds them represent a higher sphere: the abode of the free and redeemed spirit

- 31. Tomb of Lorenzo de' Medici 1524-31 Marble, 630 x 420 cm Sagrestia Nuova, San Lorenzo, Florence

- 32. The chapel was built between 1475 and 1483, in the time of Pope Sixtus IV della Rovere. A basic feature of the chapel itself, so obvious that it is sometimes ignored, is the papal function, as the pope's chapel and the location of the elections of new popes. The Chapel is rectangular in shape and measures 40,93 meters long by 13,41 meters wide, i.e. the exact dimensions of the Temple of Solomon, as given in the Old Testament. It is 20,70 meters high and is surmounted by a shallow barrel vault with six tall windows cut into the long sides, forming a series of pendentives between them. The walls are divided into three orders by horizontal cornices; according to the decorative program, the lower of the three orders was to be painted with fictive "tapestries," the central one with two facing cycles - one relating the life of Moses (left wall) and the other the Life of Christ (right wall), starting from the end wall, where the altar fresco, painted by Perugino, depicted the Virgin of the Assumption, to whom the chapel was dedicated. The wall paintings were executed by Pietro Perugino, Sandro Botticelli, Domenico Ghirlandaio, Cosimo Rosselli, Luca Signorelli and their respective workshops, which included Pinturicchio, Piero di Cosimo and Bartolomeo della Gatta. The ceiling was frescoed by Piero Matteo d'Amelia with a star-spangled sky. Michelangelo was commissioned by Pope Julius II della Rovere in 1508 to repaint the ceiling; the work was completed between 1508 and 1512. He painted the Last Judgement over the altar, between 1535 and 1541, being commissioned by Pope Paul III Farnese.

- 33. In planning the architectural design Michelangelo first had to accommodate his program to the pre-existing building, including the windows, which were the source of light for his decoration. The wreath of openings still provides the principal viewing light. Michelangelo devised a long central area framed by a fictitious marble cornice and separated into nine sections by broad pilaster strips bent across the ceiling, also in imitation white marble. Sections of alternating dimensions are framed between wider and narrower bands. Within them Michelangelo varied the size of the actual narratives, giving only the smaller ones a marble frame. Four ignudi (male nudes), among the most admired elements of the ceiling, ostensibly support ribbons attached to large medallions painted to look like bronze. Twenty in all, they are in different poses, producing, together with the Prophets and Sibyls, a "handbook" of alternatives for the seated figure for later artists. At the corners of the ceiling Michelangelo has painted four salvation subjects, including David and Goliath and Judith and Holofernes. Triangular-shaped compartments are repeated in a continuous band along the entire border of the ceiling; they contain bronze-colored nudes that alternate with the renowned Prophets and Sibyls set into marble thrones which, in turn, have paired marble putti in a variety of poses and positions that expand upon the tradition of Donatello and Luca della Robbia. The ancestors of Christ are painted on the flat side walls, the only section of the decoration that did not require the visual adjustments posed by painting on a curved surface.

- 36. This fresco was commissioned by Pope Clement VII (1523-1534) shortly before his death. His successor, Paul III Farnese (1534-1549), forced Michelangelo to a rapid execution of this work, the largest single fresco of the century. The first impression we have when faced with the Last Judgment is that of a truly universal event, at the center of which stands the powerful figure of Christ. His raised right hand compels the figures on the left-hand side, who are trying to ascend, to be plunged down towards Charon and Minos, the Judge of the Underworld; while his left hand is drawing up the chosen people on his right in an irresistible current of strength. Together with the planets and the sun, the saints surround the Judge, confined into vast spatial orbits around Him. For this work Michelangelo did not choose one set point from which it should be viewed. The proportions of the figures and the size of the groups are determined, as in the Middle Ages, by their single absolute importance and not by their relative significance. For this reason, each figure preserves its own individuality and both the single figures arid the groups need their own background. The figures who, in the depths of the scene, are rising from their graves could well be part of the prophet Ezechiel's vision. Naked skeletons are covered with new flesh, men dead for lengths of time help each other to rise from the earth. For the representation of the place of eternal damnation, Michelangelo was clearly inspired by the lines of the Divine Comedy: Charon the demon, with eyes of glowing coal/Beckoning them, collects them all,/Smites with his oar whoever lingers. According to Vasari, the artist gave Minos, the Judge of the Souls, the semblance of the Pope's Master of Ceremonies, Biagio da Cesena, who had often complained to the Pope about the nudity of the painted figures. We know that many other figures, as well, are portraits of Michelangelo's contemporaries. The artist's self-portrait appears twice: in the flayed skin which Saint Bartholomew is carrying in his left-hand, and in the figure in the lower left hand corner, who is looking encouragingly at those rising from their graves. The artist could not have left us clearer evidence of his feeling towards life and of his highest ideals.

- 38. Michelangelo set the seal on his plan by removing the equestrian statue of Marcus Aurelius, which the Romans had long believed to be Constantine the Great, from the Lateran, and placing it on a pedestal of his design in the centre of the Capitoline hill. As emblem of the Imperial power of Rome, the Caesar holding sway over a limitless area rises from the center of the sun, whose twelve rays branch out into a linear pattern of multiple dimensions; by means of intersecting lines six times twelve concentric fields are obtained. It is clear that in conjunction with the twelve-pointed sun upon which he rides, they represent the planets (which designation includes sun and moon), passing through the twelve mansions of the Zodiac. As an assiduous reader of the Divine Comedy Michelangelo may have come by these ideas, familiar to other medieval minds, Dürer among them. The monarchic idea, too, derives from Dante. The whole design fits into an ellipse which represents the earthly correspondence to the divine sphere, but it is an oval which contains two focal points because dualism in the world had displaced the true center. It is no accident or artist's whim that the number seven is the key theme of the Capitol. It is found in the mystical speculation of all ages. Capitoline Hill Piazza Campidoglio, Rome

- 40. All extant documents and the results of modern research attest that the Old Basilica of Saint Peter's was a beautiful church and the joy of every pilgrim. But it was falling to pieces, and the prevalent taste for the spectacular determined the Popes to pull down the venerable building and replace it by a new and more imposing church. Many plans were advanced and discarded; many changes made. Each Pope and each newly appointed architect criticized, chopped and changed the earlier plans. What emerged were bits and fragments, the most excellent being those left by Bramante, though artists like Raphael, Baldassare Peruzzi and Antonio da Sangallo the Younger had made their contributions. Weighty tomes were compiled recording the complicated history of this building. In 1547 Pope Paul III entrusted Michelangelo with the supervision of the plans, but years went by before he managed to introduce some order into them and impose unity on the inchoate mass of designs and materials. He reduced Bramante's elaborate plans to a central edifice and a mighty dome. This dome, finished after his death, became the largest in the world. Bramante had envisaged a square dome with four towers and a light, balanced arrangement of aisles and cloisters, the whole made up of autonomous and coordinated parts. Michelangelo's plan was grander and more simple, with an elliptical parabolic cupola dominating the whole design. The internal structure of the church is cruciform, with barrel vaulting in Bramante's manner, while the castle-like façade suggests worldly rather than spiritual dominion. The gallery at the base of the cupola is almost Gothic in character. The walls below, broken by superimposed windows in groups of two and three, wedged between steeply rising pilasters with angulate Corinthian capitals, support the architrave, the cornice and the powerful attic story. All this is but a basis for, and a prelude to, the great dome which dominates and blesses the Campagna Romana, or what is left of it today. Michelangelo Dome of St. Peter’s

- 41. Corregio Deposition c. 1528 Oil on wood, 313 x 192 cm

- 42. The Deposition can perhaps justly be described as the artist's masterpiece. The compositional idea is extravagant and totally unprecedented: an inextricable knot of figures and drapes that pivots around the bewildered youth in the foreground and culminates above in the two lightly hovering figures emerging from vague background. The compositional complexity is accompanied by a significant and probably deliberate ambiguity in the representation of the subject, which may be interpreted as halfway between the theme of the Deposition and that of the Pietà or Lamentation over the Dead Christ. The painting appears to represent the moment in which the body of Christ, having been taken down from the cross, has just been removed from the mother's lap. The Virgin, visibly distraught, and perhaps on the point of fainting, still glazes longingly towards her Son, and gestures with her right arm in the same direction. In the centre of the painting, the moment of the separation is underlined by the subtle contact of Mary's legs with those of Christ, now freed from his Mother's last pathetic embrace. An intense spiritual participation in the grief of the event profoundly affects the expressions and attitudes of all the figures present, even that of the woman turned away from the onlooker, probably Mary Magdalene, who communicates her anguished psychological condition by reaching out sympathetically towards the swooning body of the Virgin. Some scholars have interpreted the two young figures holding up the deceased's body as angels in the act of drawing Christ away from the main group and leading him finally into the arms of his Father. The general direction of the movement is, in fact, a rising one, and is created by the ethereal quality of the weightless figures, and their slow, almost dance-like rhythm. The two presumed angelic presences, moreover, seem to be unaffected by the weight of the lifeless body, and the figure in the foreground appears to be in the act of raising himself up by lightly pressing down on the front part of his foot.

- 43. Madonna dal Collo Lungo (Madonna with Long Neck) 1534-40 Oil on panel, 216 x 132 cm Galleria degli Uffizi, Florence This was painted for the church of Santa Maria dei Servi at Parma. It is the masterpiece of the culminating period in the art of Parmigianino, done almost the same time as the frescoes of the Steccata at Parma. The painter worked upon the picture for six years, but this notwithstanding, it remained unfinished. It is a work of intense if somewhat aloof poetical feeling, this effect mainly arising from the splendid abstraction of the forms, so smoothly rounded under the cool and polished color.

- 44. This is one of Bronzino's greatest portraits. It is exemplary of the mannerist style of portraiture. The self-possessed aloofness of the sitter and the austere elegance of the Palace interior are hallmarks of the courtly style of portraiture he created for Medicean Florence. Although the sitter cannot be identified, he is likely a member of Bronzino's close circle of literary friends. The book held by the sitter in the portrait, the fanciful table and chair, with their grotesque decorations, introduce intentionally witty and capricious motifs: visual analogues to the sorts of literary conceits enjoyed by this cultivated society . Bronzino Portrait of a Young Man c. 1540 Oil on wood, 96 x 75 cm Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

- 45. Most of Vasari’s account of his visit to the Anguissola family is devoted to Sofonisba, about whom he wrote: ‘Anguissola has shown greater application and better grace than any other woman of our age in her endeavors at drawing; she has thus succeeded not only in drawing, coloring and painting from nature, and copying excellently from others, but by herself has created rare and very beautiful paintings’. Sofonisba’s privileged background was unusual among woman artists of the 16th century, most of whom, like Lavinia Fontana , were daughters of painters. Her social class did not, however, enable her to transcend the constraints of her sex. Without the possibility of studying anatomy, or drawing from life, she could not undertake the complex multi-figure compositions required for large-scale religious or history paintings. She turned instead to the models accessible to her, exploring a new type of portraiture with sitters in informal domestic settings. The influence of Campi, whose reputation was based on portraiture, is evident in her early works, such as the Self-portrait (Florence, Uffizi). She was employed as the court painter for Phillip II of Spain. Sofonisba was one of the first women to gain a international reputation as a painter. She studied under Campi until he moved away and this established a precedent of encouraging male painters to take on female students. Michelangelo even sent her some drawings, which she copied and sent back to him for criticism. She was a prolific painter: more than 30 signed pictures survived from her years in Cremona, with a total of about 50 works that have been securely attributed to her. Late in her life she was visited by a young painter Anthony van Dyck. A drawing of her appears in his sketchbooks, along with excerpts of the advice she gave him about painting. Nevertheless it is clear that she was an innovative portraitist, whose international stature inspired many young women to become painters. Sofonisba Anguissola (1532-1625)

- 47. Charming portrait of her siblings showing an insight into their personalities. Very much like a studio pose today.

- 48. The Rape of the Sabines marked the climax of Giambologna's career as an official Medici sculptor. This great marble was unveiled in the Loggia dei Lanzi in January 1583 in place of Donatello's Judith. The group is indebted to Giambologna's study of Hellenistic sculpture, particularly in the voids which penetrate the three interlocked figures. On a technical level it represents the fulfillment of an aspiration from antiquity. Ancient sources record sculptures made from a single block, a claim which the Renaissance discovered was not true. Giambologna intended to surpass antiquity by sculpting a large group from a single block that also involved a complicated lift. The result is the first sculpture with no principal viewpoints, it forms a spiral that is the culmination of the "figura serpentina". This sculpture, in contrast, was designed with the intention of making the viewer examine it from every direction. When the face of the Roman is visible, the expressions of either of the Sabines are not, and visa versa; thus, the viewer is forced to take in the sculpture from all 360 degrees. According to this story, there were originally two groups of people in the region of Rome: the Sabines and the shepherd-warriors who followed Romulus. Thus, Romulus invited the neighboring Sabines to a festival, in which he and his men stole their women and made them their wives. Depending on the source of the story, the Sabines either agreed directly to make Romulus their king, or else a few more wars ensued, all of which the Sabines lost, and then the Sabines agreed to support Romulus as their king. Giovanni da bolgna Rape of the Sabines 1581-83 Marble, height: 410 cm Loggia dei Lanzi, Florence It is known from various documents that one of Giambologna's goals was to surpass Michelangelo as a great sculptor; however, it is difficult to ascertain whether he eventually did or did not surpass him. It is known that over his lifetime Giambologna did produced many magnificent works of art, but whether or not he eclipsed Michelangelo is disputable. Nevertheless, it can be determined from many of Giambologna's works of art that he did was very influenced by the works Michelangelo produced; oftentimes, his sculptures slightly imitate the postures and the positions found in Michelangelo's sculptures.

- 49. Giambologna designed the Appenine, a fountain of sorts set in a garden of titillating marvels at the Medici Villa at Pratolino. The theatrical work combined several Mannerist themes: the colossus, the fountain, the interaction between art and nature. It was carved partly out of living rock and embellished with dripped stucco, lava and other materials to appear organic. Appenine 1570-80 Rock, lava, brick, etc., height: 10 m Garden of the Villa Medici, Pratolino

- 50. Situated on the top of a hill just outside the town of Vicenza, the Villa Capra is called the Villa Rotonda, because of its completely symmetrical plan with a central circular hall. The building has a square plan with loggias on all four sides, which connect to terraces and the landscape. At the center of the plan, the two story circular hall with overlooking balconies was intended by Palladio to be roofed by a semicircular dome. However, after his death, a lower dome was built, designed by Vincenzo Scamozzi and modeled after the Pantheon with a central oculus originally open to the sky. The proportions of the rooms are mathematically precise, according to the rules Palladio describes in the Quatro Libri. The building is rotated 45 degrees to south on the hilltop, enabling all rooms to receive some sunshine. The villa is asymmetrically sited in the topography, and each loggia, although identical in design, relates to the landscape it enfronts differently through variations of wide steps, retaining walls and embankments. Thus, the symmetrical architecture in asymmetrical relationship to the landscape intensifies the experience of the hilltop. The northwest loggia is set recessed into the hill above an axial entry from the front gate. This axis is flanked by a service building and continues visually to a chapel at the edge of the town, thus connecting villa and town The Villa Rotunda is a product of simple geometries arrayed around a central dome. The residence can be split into four nearly-identical quadrants

- 51. Giovanni Bellini The Feast of the Gods 1514 Oil on canvas, 170 x 188 cm National Gallery of Art, Washington The Feast of the Gods was Giovanni Bellini's last great painting and one of only a few that he executed on canvas. The artist, whose career began in the 1450s, was trained to paint on wooden panels, which require a very meticulous application of pigment. When he worked on canvas late in his career, Bellini retained his tight, precise brushwork. The flesh tones, iridescent silks, and even the foreground pebbles here demonstrate his delicate touch. According to the current interpretations, the scene illustrates a passage from Ovid's Fasti (The Feasts), a long classical poem that recounts the origins of many ancient Roman rites and festivals. Ovid (43 B.C. - A.D. 17), describing a banquet given by the god of wine, mentioned an incident that embarrassed Priapus, god of virility. The beautiful nymph Lotis, shown reclining at the far right, was lulled to sleep by wine. Priapus, overcome by lust, seized the opportunity to take advantage of her and is portrayed bending forward to lift her skirt. His attempt was foiled when an ass, seen at the left, "with raucous braying, gave out an ill-timed roar. Awakened, the startled nymph pushed Priapus away, and the god was laughed at by all." Priapus, his pride wounded, took revenge by demanding the annual sacrifice of a donkey. The ass stands next to Silenus, a woodland deity who used the beast to carry wood, thus wears a keg on his belt because he was a follower of Bacchus, god of wine. Bacchus himself, seen as an infant, kneels before them while decanting wine into a crystal pitcher.

- 52. Reading from left to right, the principal figures are: Silenus, a woodland god attended by his donkey Bacchus, the infant god of wine crowned with grape leaves Faunus or Silvanus, an old forest god wearing a wreath of pine needles Mercury, the messenger of the gods carrying his caduceus or herald's staff Jupiter, the king of the gods accompanied by an eagle An unidentified goddess holding a quince, a fruit associated in the ancient world with marriage Pan, a satyr with a grape wreath who blows on his shepherd's pipes Neptune, the god of the sea sitting beside his trident harpoon Ceres, the goddess of cereal grains with a wreath of wheat Apollo, god of the sun and the arts, crowned by laurel and holding a Renaissance stringed musical instrument, the lira da braccio, in lieu of a classical lyre Priapus, the god of virility and of vineyards with a scythe, used to prune orchards, hanging from the tree above him Lotis, one of the naiads, a nymph of fresh waters who represents chastity. These deities are waited upon by three naiads, nymphs of streams and brooks, and two satyrs, goat-footed inhabitants of the wilderness. On the distant mountain, which Titian added to Bellini's picture, two more satyrs cavort drunkenly and a hunting hound chases a stag

- 54. This work is one of the mysteries of European painting: in spite of its undeniable quality and epochal importance, opinions are divergent concerning both its creator and its theme. It is the outstanding masterpiece of the Venetian Renaissance, the summit of Giorgione's creative career, so much so that according to some it may have been painted, or at least finished, by Titian rather than Giorgione. The painting has been interpreted as an allegory of Nature, similar to Giorgione's Storm, which was undeniably painted by him; it was even viewed as the first example of the modern herdsman genre. Its message must be more complex than this. It is likely that the master consciously unified several themes in this painting, and the deciphering of symbols required a degree of erudition even at the time of its creation. During the eighteenth century the painting was known by the simple name of "Pastorale" and only subsequently was it given the title "Fête champêtre" or "Concert champêtre", owing to its festive mood. Modern research has pointed out that the composition is in fact an allegory of poetry. The female figures in the foreground are the Muses of poetry, their nakedness reveals their divine being. The standing figure pouring water from a glass jar represents the superior tragic poetry, while the seated one holding a flute is the Muse of the less prestigious comedy or pastoral poetry. The well-dressed youth who is playing a lute is the poet of exalted lyricism, while the bareheaded one is an ordinary lyricist. The painter based this differentiation on Aristotle's "Poetica". The scenery is characterized by a duality. Between the elegant, slim trees on the left, we see a multi-leveled villa, while on the right, in a lush grove, we see a shepherd playing a bagpipe. Yet the effect is completely unified. The very presence of the beautiful, mature Muses provides inspiration; the harmony of scenery and figures, colors and forms proclaims the close interrelationship between man and nature, poetry and music. Pastoral Symphony Girgione

- 55. Titian was neither such a universal scholar as Leonardo, nor such an outstanding personality as Michelangelo, nor such a versatile and attractive man as Raphael. He was principally a painter, but a painter whose handling of paint equaled Michelangelo's mastery of draughtsmanship. This supreme skill enabled him to disregard all the time-honored rules of composition, and to rely on color to restore the unity which he apparently broke up. It was almost unheard of to move the Holy Virgin out of the center of the picture, and to place the two administering saints - St Francis, who is recognizable by the Stigmata (the wounds of the Cross), and St Peter, who has deposited the key (emblem of his dignity) on the steps of the Virgin's throne - not symmetrically on each side, but as active participants of a scene. In this altar-painting, Titian had to revive the tradition of donors' portraits, but did it in an entirely novel way. The picture was intended as a token of thanksgiving for a victory over the Turks by the Venetian nobleman Jacopo Pesaro, and Titian portrayed him kneeling before the Virgin while an armored standard-bearer drags a Turkish prisoner behind him. St Peter and the Virgin look down on him benignly while St Francis, on the other side, draws the attention of the Christ Child to the other members of the Pesaro family, who are kneeling in the corner of the picture. The whole scene seems to take place in an open courtyard, with two giant columns which rise into the clouds where two little angels are playfully engaged in raising the Cross. Titian's contemporaries may well have been amazed at the audacity with which he had dared to upset the old-established rules of composition. They must have expected, at first, to find such a picture lopsided and unbalanced. Actually it is the opposite. The unexpected composition only serves to make it gay and lively without upsetting the harmony of it all. Titian Madonna with Saints and Members of the Pesaro Family 1519-26

- 56. The Venus of Urbino was painted for Guidobaldo della Rovere, the heir of Francesco Maria della Rovere, Duke of Urbino. Titian's Venus has nothing to do with Giorgione's idealized image of female beauty, it is normally interpreted as an allegory of marital love. There have been some suggestions that there might be a connection with the wedding of Guidobaldo della Rovere and Giuliana Varano in 1534. This is an extremely fine composition. It invites us to dwell on more than just the warm, golden figure of this young woman with her cascading curls and the attractive, carefully studied movement of her arm. Observe the way the sheet has been painted, with masterful blends of color, the small dog lazily curled up asleep, the amusing touch of the two maids rummaging in the chest, the world outside the window, and the malicious, but at the same time ingenious expression of the young Venus. There is an intimacy of this scene of almost domestic simplicity which places the whole composition in a warm, human, temporal reality Titian The Venus of Urbino 1538

- 57. Man with Gloves 1523-24

- 59. The church of San Giorgio Maggiore was built on the San Giorgio Island between 1566 and 1600 using the design of Palladio. After 1590 the workshop of Tintoretto was commissioned to paint big canvases for decorating it. Due the large number of commissions, Tintoretto in his late years increasingly relied on his coworkers. However, three surviving paintings placed in a chapel consacrated in 1592 - The Harvest of Manna, The Last Supper and Entombment - were certainly painted by Tintoretto himself. Tintoretto painted the Last Supper several times in his life. This version can be described as the fest of the poors, in which the figure of Christ mingles with the crowds of apostles. However, a supernatural scene with winged figures comes into sight by the light around his head. This endows the painting with a visional character clearly differentiating it from paintings of the same subject made by earlier painters like Leonardo. Tintoretto The Last Supper 1592-94 Oil on canvas, 365 x 568 cm S. Giorgio Maggiore, Venice

- 60. This immense canvas was executed for the refectory of the convent of S. Giorgio Maggiore at Venice. It was removed in 1799 and taken to the Louvre. The picture portrays a sumptuous imaginary palace with about a hundred and thirty guests, portraits of celebrities of the period, of Veronese himself and of his friends dressed in richly coloured costumes.

- 61. Originally titled The Last Supper of Christ , the room-sized painting depicts a strange collection of near-life-size figures either seated or milling about near Jesus at a long banquet table. In addition to garden variety Apostles, Veronese kicked it up a notch with a few dwarfs, some armed German soldiers, drunks, dogs, and clowns, among other things. It was the fifth Last Supper he had painted in his career to that point, and maybe he was getting a little tired of the subject. Why not have a little fun? The friars of Santi Giovanni and Paolo didn't see it that way. It wasn't the painting they commissioned or wanted. When Veronese refused to change it, they had him hauled before the McCarthy Commission of the day: the Inquisition. What follows is an edited transcript of that appearance. It's quite funny, though I doubt Veronese saw the situation that way. You can imagine the stern, crabby, hyper-serious Inquisitors in their 30-pound wigs and gaudy silk outfits glaring down at the artist. And you can hear Veronese wriggling and sweating. But what's really interesting is the epic, eternal struggle between humorless authority and a youthful artistic spirit. And you can hear the collision of two very different views of art, one literal and reason-bound, the other highly intuitive and imagination-driven. There was a happy ending. The Inquisition ordered him to make changes. He agreed, but amazingly, in the end, the only thing he did was to paint the words "FECIT D. COVI. MAGNVS LEVI- LVCAE CAP. V" on the canvas, effectively retitling the work Feast At The House of Levi , after a more party-friendly event that found in the Gospel of Luke.

Notes de l'éditeur

- Madonna of the Rocks, Leonardo da Vinci 1485 6’3” x 3’7” Forms emerge from darkness Spiritual illumination from faces Pyramid shape Mary hand forms a halo over head Christ’s hand raised in blessing Plants and geological features very accurate

- The Last Supper, by Leonardo da Vinci 1495-97 29’ 10” x 13’ 9” “ I say unto you, that one of you shall betray me” Each showing emotion Judas only one not involved in discussions Huddle at table with hand on money bag All lines merge to Jesus’ head Curved pediment above his head served as a halo Formally and emotionally, his most impressive work

- Mona Lisa, Leonardo da Vinci 1503-1505 World’s most famous portrait One of his favorite pictures Mona Lisa = Lisa di Antonio Maria Gherandini “Mona” - Italian version of madonna or my lady Complete very few painting, due to his perfectionism, restless experimentalism, and far-ranging curiousity.

- Plato and Aristotle on either side of center axis Plato points skyward to indicate his idealistic worldview Aristotle gestures to ground to to show his concern with the real world Metaphysical philosophers on Plato’s side Physical scientists on Aristotle’s side Raphael on extreme right Figures grouped and placed on purpose

- Annunciation Compare with Medieval version

- Captive, Michelangelo Example of statue already in marble, he just has to release it Series of Captives line hall leading to the David.

- Pieta, Michelangelo, 1498-99 Mary cradling the dead body of Christ Beautiful faithful mary Polish and luminosity of marble cannot be capture by camera.

- Pieta II, Michelangelo

- David, Michelangelo 1501-1504

- Moment he sees Golith on the horizen