A Sociological Study Of Patterns And Determinants Of Child Labour In India

- 1. A sociological study of patterns and determinants of child labour in India Barsa Priyadarsinee Sahoo Abstract Purpose – The purpose of this paper is to understand the patterns and incidence of child labour in India and to examine the magnitude of child labour across different social groups. It analyses the impact of the socio-economic background of the children on their participation in the labour market. Design/methodology/approach – The paper primarily relies on the data collected from secondary sources. The census of India data and the National Sample Survey Organisation (NSSO) 66th round data (2009–2010) on employment and unemployment in India for the study. The dependent variable on child labour has been computed by the author for the analysis in the paper. Findings – The findings of the paper suggest that poverty is not the only determinant of child labour, but gender and caste of a person is also a significant factor for child labour. The study found that children from lower-caste backgrounds in India seem to participate more in the labour market. In terms of gender, the study found that boys are more likely to engage in economic activities or paid jobs while girls are more likely to engage in household activities. Originality/value – Data used in this paper has been extracted by the author from unit level data provided by NSSO. The variables used for the analysis in the presented paper has been constructed by the author and the figures provided are the result of the author’s estimation on data. Keywords India, Determinants, Child labour, Pattern, NSS, Child work, Incidence Paper type Research paper 1. Introduction Child labour is a matter of grave concern in many parts of the world, especially in developing countries. Child labour is described as a complex and multidimensional issue due to its features and impact on the well-being of children, inadequate data and the need for a comprehensive solution. It has a negative impact on the social, economic and developmental growth of a country. Global estimates of the International Labour Organisation (ILO) show that 152 million children are working worldwide and the incidence is very high for the developing countries (International Labour Organisation, 2017). Statistics reveal that India is one of the countries with the highest numbers of child labourers in the world (NCPCR Position Paper, 2008; International Labour Organisation, 2013, 2017). According to the 2011 Census, 10.1 million children in the age group of 5–14years are employed in India. If we examine the trend from 1971 onwards, we can see an increasing trend (Table 1). It can be seen that the total number of child labour was declining from 1981 to 1991, but again in 2001, there was an increase in the number of child labourers from 11.28 million in 1991 to 12.66 million in 2001. An increase of over one million child labourers from 1991 to 2001 signifies that the problem of child labour is escalating. Though the census 2011 figures show a slight reduction in the number of child labour still, the figure is high. Therefore, it is a matter of grave concern for India, which necessitates immediate attention. Child labour, as a social evil, did not emerge suddenly. It had always been present in some form or other. However, it was during the industrial revolution that the problem was much more Barsa Priyadarsinee Sahoo is an Assistant Professor based at School of Law, Alliance University, Bangalore, India. Received 24 October 2020 Revised 24 February 2021 Accepted 11 March 2021 DOI 10.1108/JCS-10-2020-0067 © Emerald Publishing Limited, ISSN 1746-6660 jJOURNAL OF CHILDREN’S SERVICES j

- 2. visible with the employment of children in hazardous industries. One of the primary reasons for hiring children in industries was that they were considered as a cheap substitution to adult labour (Marx, 1956). Mines were the places with severe child labour. Liten (2010) mentioned that during industrialisation, 50% of the factory labour force was children and 30% were working in coal mines. Radhakamal Mukerjee (1945) in his book “Indian Working Class” mentioned that in 1936, 73.6% of the total child population was working in perennial factories whereas 26.4% were working in seasonal factories. Many children were employed in cotton and jute mills and coal mines; they were even employed for underground work (Deshta and Deshta, 2000). The jute mills of Bengal alone employed as many as 26,500 children in 1925 and in Shellac factories, children constitute around 10% of the total workforce. The situation in the beedi industry was even worse. Hundreds of young boys were employed for long hours for beedi making in an unsatisfactory environment and without adequate medical examinations (Mukerjee, 1945). However, the problem of child labour can not be studied in isolation as it is influenced by many factors. The socio-economic status of the family of the child, cultural norms and weak state legislation can also contribute to the increasing number of child labour. In India, most discussions on the determinants of child labour start with discussing low household income and poverty. The prominent work of Basu and Van (1998) was framed upon Table 1 State wise distribution of child labour in India (census 1971–2011) Sl. no. Name of the states 1971$ 1981$ 1991$ 2001$ 2011# 1 Andaman and Nicobar Island 572 1,309 1,265 1,960 1,672 2 Andhra Pradesh 1,627,492 1,951,312 1,661,940 1,363,339 673,003 3 Arunachal Pradesh 17,925 17,950 12,395 18,482 17,029 4 Assam 239,349 327,598 351,416 284,812 5 Bihar 1,059,359 1,101,764 942,245 1,117,500 1,088,509 6 Chandigarh 1,086 1,986 1,870 3,779 4,322 7 Chhattisgarh 364,572 257,773 8 Dadra and Nagar Haveli 3,102 3,615 4,416 4,274 2,055 9 Daman and Diu 7,391 9,378 941 729 881 10 Delhi 17,120 25,717 27,351 41,899 36,317 11 Goa 4,656 4,138 10,009 12 Gujarat 518,061 616,913 523,585 485,530 463,077 13 Haryana 137,826 194,189 109,691 253,491 123,202 14 Himachal Pradesh 71,384 99,624 56,438 107,774 126,616 15 Jammu and Kashmir 70,489 258,437 175,630 114,923 16 Jharkhand 407,200 400,276 17 Karnataka 808,719 1,131,530 976,247 822,615 421,345 18 Kerala 111,801 92,854 34,800 26,156 45,436 19 Lakshadweep 97 56 34 27 81 20 Madhya Pradesh 1,112,319 1,698,597 1,352,563 1,065,259 700,239 21 Maharashtra 988,357 1,557,756 1,068,427 764,075 727,932 22 Manipur 16,380 20,217 16,493 28,836 34,086 23 Meghalaya 30,440 44,916 34,633 53,940 44,469 24 Mizoram 6,314 16,411 26,265 7,778 25 Nagaland 13,726 16,235 16,467 45,874 63,790 26 Odisha 492,477 702,293 452,394 377,594 334,416 27 Puducherry 3,725 3,606 2,680 1,904 2,173 28 Punjab 232,774 216,939 142,868 177,268 176,645 29 Rajasthan 587,389 819,605 774,199 1,262,570 848,386 30 Sikkim 15,661 8,561 5,598 16,457 10,390 31 Tamil Nadu 713,305 975,055 578,889 418,801 284,232 32 Tripura 17,490 24,204 16,478 21,756 13,560 33 Uttar Pradesh 1,326,726 1,434,675 1,410,086 1,927,997 2,176,706 34 Uttaranchal - - - 70,183 82,431 35 West Bengal 511,443 605,263 711,691 857,087 550,092 India 10,753,985 13,640,870 11,285,349 12,666,377 10,128,663 Note: Census could not been conducted Source: $: Ministry of Labour and Employment and #: Authors’ calculation of child labour using census data 2011 (includes main and marginal worker) jJOURNAL OF CHILDREN’S SERVICES j

- 3. the “luxury axiom” and “substitution axiom”. They have argued that child leisure is a luxury commodity to the poor household and the low adult wage is the main reason for which the children cannot enjoy that luxury. Kothari (1983), in her study on the matchstick industry in Sivakasi in the state of Tamil Nadu, found that children were forced to leave the school to support the family economy. However, some scholars (Jensen and Nielsen, 1997; Remington, 1996; Satyarthi, 2006) argue that poverty is not the only determinant of child labour instead, there exists a potential link between education and child labour. Weiner (1989) argued that child labour in India is very much related to dropout rates in schools and the situation is worst in rural areas, particularly amongst girls in comparison to boys and more specifically amongst the lower castes. Similarly, Kiran Bhatty (1996) argued against the conventional idea of poverty as the root cause of child labour. For her, more than poverty, social attitudes and sensibilities also lead to child labour. Some empirical studies (Chaitanya, 1991; Chamarbagwala, 2008; Emerson and Knabb, 2006) also suggest that inequality of opportunity is the reason for the intergenerational transmission of child labour rather than poverty. Apart from these factors, parents’ level of education also plays an essential role regarding the decision on child labour (Fors, 2008; Mukherjee and Das, 2007, 2008). Gender of the child too becomes very crucial in the decision-making process of the parents concerning child labour and schooling, particularly for a girl child. However, most of the earlier debates on child labour did not focus on gender roles, particularly for the girl child labour. One of the reasons behind the absence of work on girl child labour is the type of work they are engaged in. While one can see boys working in the factories and hazardous conditions, girls mostly work at home and are, therefore, invisible sometimes (Burra, 1995). Burra argued that a strong “sex typing” of work existed in relation to the work that female or male children do in agriculture, household or unorganised industries. Studies suggest that Gender bias depends on the economic condition of the parents (Kumar, 2013). When parents are better off, then both male and female children get an equal amount of schooling. However, when parents are poor, then it creates gender discrimination where female children receive less education than their male counterparts. The ideas of gender inequality that is rooted in the Indian mindset affect the magnitude of child labour in the country. Furthermore, the religious belief system also affects the incidence of child labour of a country. Though specific religions deliberately do not promote child labour, but different religions give rise to powerful ideas about the appropriate activities of children. In India, the Hindu caste system is an important structuring principle and influence on the roles undertaken by the children (Boyden and Morrow, 2015). The link between caste and occupation, which has existed for many years, is evident even amongst the child labourers in India. Although people are moving away from their caste occupation, but because of the years of suppression and oppression the lower caste communities still have not been able to come out of their previous status. A study of the relationship between caste and child labour in urban Bihar found that Scheduled Castes (SC)/Scheduled Tribes (ST) children were hand- picked to work as ragpickers, barbers and cobblers, amongst other lowly jobs while non-SC/ ST children are chosen to labour at parties and weddings because of the concept of “purity” promulgated by those who believe in the caste system (Chowdhury, 2020). Even some empirical studies (Venkateswarlu, 1998; Agrawal, 2004) found support for the argument that children from a lower-caste group are more likely to work in comparison to the upper castes. Like the caste system, the age-old tradition and beliefs also influence the parent’s decision to some extent. For instance, in an ethnographic study on glass industries in Firozabad, Chandra (2009) found that most of the household interviewed were practicing the bangle and glasswork since generations and they believe that this occupation is deeply rooted in their culture and tradition. This bangle and glass making has been so much intermingled with their life that children were attracted to these occupations from their childhood. Similarly, Bhatty (1996) says that parents sometimes do not want to send their children to school because they believe the school will detach them from the village economy and also jJOURNAL OF CHILDREN’S SERVICES j

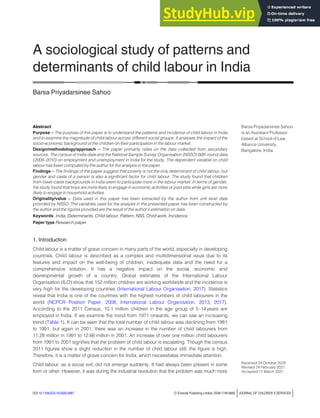

- 4. education will give them an aspiration for white collar jobs, which is hard to get. Hence, the beliefs and practices also determine whether children will work or not. Similarly, sometimes the demographic factors such as locality, geographical area and ecological condition forces children to work. Bahar (2014) argued that though children work both in rural and urban areas, but the percent of children are more in rural areas particularly in agriculture in comparison to urban areas. Kothari (1983) in her study on the match stick industry in Sivakasi, Tamil Nadu found that children were forced to leave school to support the family economy. Because, in “Ramanathpuram” (the study area), most of the people, although have agricultural land, but they largely depend on the rainfall, which affects the cultivation and makes life difficult in the dry seasons, which pave the way to work in the match and fireworks industry. Hence, geographical location and climate also sometimes determine child labour. Thus, there are many factors, which influence the nature and incidence of child labour of a country. As discussed above, apart from poverty, religious ideas, the value system and the gender norms also affect the incidence of child labour. However, the value system, religious belief and gender norms vary across communities and societies. Hence, to understand the issue of child labour in an Indian context, the author has constructed a socio-economic paradigm of child labour with reference to the reviewed literature. 2. Socio-economic paradigm of child labour Socio-economic paradigm shapes perception and practices within the disciplines according to its subject matter. It shapes what we look at, how we look at things, what we label as a problem and what problem we consider for worth investigation and what methods are preferred for the study. Socio-economic paradigm regards child labour as the consequence of unprecedented changes in socio-economic structure of society. This paradigm talks about the relationship and interaction between children and economic status within their immediate setting such as family and social networks. It also discusses about the social system and economic structure, which impact upon the immediate familial and social setting in which children are situated and can examine the implementation of social policies and welfare programmes of government. Socio-economic paradigm examines various determinants that are responsible for the existence of child labour after the implementation of various policies and programmes of government. These determinants of child labour can be understood through a diagram. This socio-economic paradigm helps the author to understand the issue of child labour as a multidimensional issue, and hence, any umbrella solution cannot solve the issue of child labour. To eradicate the problem of child labour every contributing factor needs to be examined properly and solutions need to be provided. Hence, the nature and problem of child labour can be understood and analysed with reference to Indian society by using the socio-economic paradigm (Figure 1). 3. Conceptualising child labour Defining child labour has always been a contested issue. The concept of “child” and “childhood” have changed over time and vary across cultures, social class, age and countries (Dash et al., 2018). Child labour is the combination of two words “child” and “labour”, which have different meanings that vary across contexts. There exists a debate concerning the use of terms such as “child labour” and “child work”. Some scholars use these terms interchangeably, and for them, there is no distinction between these two terms while others think for the need of distinction between these two terms (Burra, 2005; Liten, 2002). ILO made a distinction between “child labour” and “child work” in the 1980s. Child labour includes the form of works that are exploitative and harmful to children, which mainly takes place “outside the family” “for other” and is “productive”. Child work is not harmful and it is “reproductive” in nature and it is practised at home for the child’s family (Liebel, 2004). Some studies (Bhukuth, 2008; Liten, 2006a, 2006b) jJOURNAL OF CHILDREN’S SERVICES j

- 5. consider child labour as interference in childhood, which puts an economic burden on the children and also a form of forced labour, which is “bad” and unacceptable. Child work is the activities that involve no exploitation, no interference in childhood and not even forced work but the acceptable form of work, i.e. “good work”. Taking a holistic approach, ILO defines child labour as, “works that deprive children of their childhood, their potential and dignity and that is harmful to their physical and mental development” (International Labour Organisation, 2013). This definition also includes those works that interfere with the education of the child, separate them from their families and force them to work in hazardous health conditions. In India, children working in the factories, dhabas (roadside food stalls), in carpet, lock, glass, beedi (country made cigars), bangle, match industries come under this category. Working in these areas not only endangers their health but is also harmful to their mental and moral development. In India, the two major data sources used for child labour research are the Census and National Sample Surveys (NSS). Both of these data sources do not have any direct question on child labour, rather they provide data on employment and unemployment. Hence, one has to look at the employment status and the age of the respondent to construct a variable on child labour. Moreover, the estimation of child labour depends on the definition of child and age is one of the significant criteria for the estimation of child labour as this distinguishes child labour from adult labour. Defining a “child” is as much contentious as defining child labour. Various legal documents define it differently, and it varies from country to country. Article 1 of the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child sets the age limit of a child at 18years. Various labour laws in India have different age limits for defining a child. Plantations Labour Act 1951, The Motor Transport Workers Act (1961), The Apprentices Act (1961), The Beedi and Cigar Workers (Conditions of Employment) Act, 1966, The Dangerous Machines Act (1983), The Minimum Wage Act 1984 sets the age limit of a child at 14years. The Factories Act (1948) keeps it at 15years. Child Labour (Prohibition and Regulation) Act, 1986 and The Child labour (Prohibition and Regulation) Amendment Act, 2016 sets the age at 14years. The Right of Children to Free and Compulsory Education Act (2009) defines child between 6 to 14 years, the Protection of Children from Sexual Offences Act, 2012 and The Juvenile Justice (Care and Protection of Children) Act, 2015 defines child who has not completed 18years of age. However, looking at the significant Indian laws relating to children, the present paper considers persons between 5 to 14years as children and 15 to 18years as adults. These two age categories have been used for the computation of the variables and analysis of the data. Figure 1 Socio-economic paradigm of child labour Socio-economic Paradigm of Child Labour Poverty in Family Adult Unemployment Household Size Geographical condition/ Locality Religion of the Family Family Social Values Gender of the Child Parents level of Education jJOURNAL OF CHILDREN’S SERVICES j

- 6. Taking into consideration the above-mentioned age categories and the ILO definition of child labour, the present paper creates two categories of child labour. The paper uses the term “working children” and “other workers” for analysing the data on child labour. The author defines “working children” as those children who are economically active and engaged in any form of paid work. “Other workers” include those children who are not attending any educational institution and are engaged in household work, begging and prostitution as per NSS data. A third category of “child non-workers” has been used to refer to those who are attending an educational institution, are disabled or getting any remittance. With reference to the literature reviewed the objectives of the present study are to understand the patterns and incidence of child labour in India, to examine the magnitude of child labour across different social groups and to analyse the impact of the socio-economic background of the children on their participation in the labour market. 4. Data and method 4.1 Data source The present study primarily relies on the data collected from secondary sources. The census of India data and the National Sample Survey Organisation (NSSO) 66th round data (2009–2010) on employment and unemployment have been used for the fulfillment of the objectives of the Study[1]. 4.2 Sample NSSO 66th round (2009–2010) provides questions on the employment and unemployment situation in India, which has been used for the construction of the variables and empirical analysis. NSSO adopted the stratified multi-stage sampling design, and the number of households surveyed in this round was 100,957 (59,129 in rural areas and 41,828 in urban areas) and the number of persons surveyed was 459,784 (281,327 in rural areas and 178,457 in urban areas). In the present survey, 95,818 children in the age group of 5–14years were included and 40,702 children were included in the age group of 15–18years. 4.3 Methodology The analysis has been conducted at two levels. Firstly, cross-tabulation and chi-square has been done to see if there is an association or not between the independent variables and the dependent variable. Secondly, binary logistic regression has been conducted to find out the factors affecting child labour. All the analysis has been carried out in statistical package for the social sciences (SPSS) software. Dependent variables: For the regression analysis, two dependent variables have been used by using the restricted and expansive definition of child labour, and the regression result presented in Table 4 compares the results on both dependent variables. Child labour (restricted definition): Child labour is a person between 5–14 years of age who is engaged only in economic activity. Child labour (expansive definition): Child labour is a person between 5–14 years of age who is engaged in economic activity, not attending any educational institution and engaged in household and other activities. Independent variables: Gender (male and female), sector (rural and urban), social group (SC, ST, other backward class (OBC) and general), religion (Hindu, Muslim, Christian and others), household size (04, 4–6, 6–8, 8–10, 10 and above), household type (self-employed in non- agriculture, self-employed in agriculture, agricultural labour, regular wage/salary earning, causal labours and others) and poverty [rural-below poverty line (BPL), urban-BPL, rural- above poverty line (APL), urban-APL]. jJOURNAL OF CHILDREN’S SERVICES j

- 7. 5. Empirical analysis The NSS data for the present study has been analysed using the SPSS software. The basic descriptive statistics are presented in Table 2, which shows the distribution of child labourers in India. As mentioned earlier, “working children” includes children engage only in economic activities or paid work. “Other workers” include children engage in the household and other activities and not attending any educational institution. “Child non-workers” includes children attending an educational institution and not working. This category is only for comparison with the other two categories. These three categories have been used to see the pattern and incidence of child labour in India. 5.1 Pattern of child labour in India Table 2 shows that, in India, around 4.2 million children are engaged in economic activity, which is 1.4% of the total child population. What is interesting is the percentage of the “other workers” is higher than the percentage of the “working children”. It indicates that more children are engaged in household and other activities as compared to economically active children. Hence, when the working children were combined with the other workers, the percentage got even higher for India, which stands at 8.5%. The figures on child labour provided by the Ministry of Labour and Employment (Government of India) do not include “other workers” while calculating child workers, and some scholars such as Liten (2000) have argued that including these children will magnify the problem of child labour. However, as per the Government of India (2009), these children should be at school and not at work. If they are not attending any educational institution and engaging in some work, they can be counted as child labour. Whether it is the household activity or begging or prostitution; working at the expense of education can never be helpful for any child (Orrnert, 2018). Hence, when including working children with the other workers, the percentage of working children increased to 8.5%, which is 7.1% higher than the government figures. The reason for making these two categories is to find out the difference between the government figures and the present figures so that the problem of child labour can be seen clearly. Analysis of child labourers is related to the socio-economic background of a child, which includes the composition of the household, its size, caste, religion, type of household, monthly per capita expenditure, parent’s education and parents’ occupation. 5.2 Child labour and caste Child labour and caste unfortunately continue to go hand in hand in India. Most child labour in India come from a highly impoverished family unit and belongs to a low-caste or minority community, known as SCs, STs and OBCs (Kara, 2014). Table 3 presents the distribution of children across social groups in India by age. For the 5–14 age group, though the percentage of children belonging to STs is higher amongst working children, in the case of other workers, the participation is more from SCs. The percentage of working children for Table 2 Child labourers in India: NSS 2009–2010 Categories of children Estimated population In the sample (%) Working children 4,223,218 1,371 1.4 Other workers 20,188,373 6,780 7.1 Working þ other workers 24,411,591 8,151 8.5 Child non-workers 197,325,856 87,667 91.5 Total children 221,737,447 95,818 100 Source: Derived from unit level data of NSS 2009–2010 jJOURNAL OF CHILDREN’S SERVICES j

- 8. OBC stands at 1.4%, which is lower as compared to both SCs and STs but still is greater than the percentage of working children from others (general category). In the case of children in the 15–18 age group, the percentage of children is again more from SCs, STs and OBCs as compared to the general category. It is not surprising that more children from other or general caste groups constitute the child non-workers. It means more children from the general caste are attending an educational institution whereas more children from ST are working. The reason is the opportunities for secure wages, education, access to health care, fundamental rights, land ownership and inability to access formal credit markets are seriously lacking for individuals from these sections. They are always at the verge of abuse and under these situations, it is easier for the parents to send their children for work to reduce some of the family burden (Kara, 2014). 5.3 Child labour and religion India is home to 1.2 billion people, which is almost one-sixth of the world’s population that houses a variety of ethnicities and religions. However, Hindus constitute 78% of the total population while Muslims constitute 14% and Christian constitutes 2% while other religions [2] constitute around 6% as per the census of India, 2011. Hence, Hinduism is professed by a majority population of India and Muslims and other religions are regarded as minority in India. Though the Indian constitution protects the minorities against any kind of discrimination on the grounds of religion and caste, communal tensions between Indians of various religious faiths and castes have long plagued Indian society (Majumdar, 2018). The empirical analysis also shows similar evidence. While looking at the distribution of working children across age and religious community in India, one can see in Table 4 that, amongst the 5–14 age group, 2% Muslim children are working, whereas only 0.8% Christian children are working. It indicates that 10.7% of children from the Muslim community are engaging in other activities, whereas the participation of children from the Christian community is only 3%. These figures explain that the participation of children from the Muslim community is more in both the work categories in comparison to the participation of children from the Christian community. It has been found that 96.2% of children from the Christian community is not working, which means more children from the Christian community are attending educational institutions. A chi-square test has also been conducted to find out the association between religion and working children and the P-value is less than 0.05 in all cases in India, which means religion does play some role for the participation of children in the workforce. Chi-square test for other variables such as household type, poverty and education of the head of the household has been done. The P-value of other variables came less than 0.05 except for the education of the head, which means that there is no statistically significant relationship between the education of the head and children entering the labour market. Table 3 Distribution of children across social groups in India by age Social groups Age Working children Other workers Child non-workers Total Scheduled tribe 5–14 2.0 (279) 6.9 (954) 91.1 (12,578) 100 (13,811) 15–18 21.4 (1,275) 10.2 (610) 68.3 (4,070) 100 (5,955) Scheduled caste 5–14 1.8 (300) 9.7 (1,606) 88.4 (14,576) 100 (16,482) 15–18 25.3 (1,697) 16.5 (1,108) 58.1 (3,890) 100 (6,695) Other backward castes 5–14 1.4 (504) 7.6 (2,815) 91.1 (33,777) 100 (37,096) 15–18 19.4 (2,964) 14. (2,129) 66.6 (10,157) 100 (15,250) Others 5–14 1.0 (285) 4.9 (1,396) 94.1 (26,662) 100 (28,343) 15–18 14.3 (1,829) 9.7 (1,242) 75.9 (9,688) 100 (12,759) Source: Derived from unit level data of NSS 2009–2010. N = 136,391 jJOURNAL OF CHILDREN’S SERVICES j

- 9. 5.4 Determinants of child labour With the chi-square test of independence, the study found that there is an association between the independent variables such as age, sex, locality, caste, religion and the dependent variable. Table 5 presents a comparison of the regression results of the two dependent variables in India. The first model shows the results from the restricted definition and the second model shows the results for the expanded definition. The first model shows that when controlled for all other variables, men in comparison to women have a positive and statistically significant effect, which means boys are more likely to work than girls. However, the results of the second model show a negative and significant effect for men when controlled for all other variables, which is the opposite of the first model. It shows that girls are more likely to work than boys. This difference in results appears because of the difference in the definition of the dependent variable used. Controlling for all other variables, rural in comparison to urban has a positive and significant effect in both the models, which means children from rural areas are more likely to work in comparison children from urban areas. Moreover, social groups seem to affect the probability of the working children as all the three variables SC, ST and OBC have a positive and significant effect in comparison to the general category, which indicates, that belonging to these social groups increases the probability of a child becoming child labour or joining the labour market. As per Model 1, being a Hindu does not seem to affect the probability of working as the coefficient is not significant (even though the sign suggests that children from Hindu have more probability to work). For Model 2, being a Hindu affects the probability of the children to work as it is positive and significant in comparison to other religions. Hence, Model-2 shows that Hindu children are more likely to work than children from other religious communities. The results for the Muslim community in both the models are positive and significant in comparison to other religions, which means belonging to the Muslim community increases the chances of children to work. However, the result for the Christian community is significant but negative in both the models, which indicates, that children from the Christian community are less likely to join the labour market in comparison to other religious communities. Household size too affects the probability of the working of the children as the results for all the variables under household size in Model-1 is positive and statistically significant. It indicates that children from the household size with less than 10 are more likely to work in comparison to the children from the household size of 10 and above. However, in Model 2, the coefficient for the household size with less than four members is not significant and negative, which means it does not have any effect on the working of a child. However, other variables are significant and positive, which is similar to the results of Model 1. It indicates that children belonging to a small family do not have any effect on the working decision of the children. The household type has some effect on the working of the child as all the three variables such as: self-employed in non-agriculture, self-employed in agriculture, the agricultural labourer and Table 4 Distribution of children across religious community in India by age Religious community Age Working children Other workers Child non-workers Total Hindu 5–14 1.4 (967) 6.8 (4,752) 91.8 (64,154) 100 (69,873) 15–18 19.2 (5,632) 12.1 (3,541) 68.6 (20,085) 100 (29,258) Muslim 5–14 2.0 (294) 10.7 (1,593) 87.3 (12,958) 100 (14,845) 15–18 22.1 (1,404) 18.9 (1,198) 59.0 (3,743) 100 (6,345) Christian 5–14 0.8 (51) 3.0 (202) 96.2 (6,408) 100 (6,661) 15–18 14.2 (425) 4.7 (141) 81.2 (2,437) 100 (3,003) Others 5–14 1.3 (59) 5.2 (233) 93.4 (4,147) 100 (4,439) 15–18 14.9 (312) 10.3 (215) 74.9 (1,569) 100 (2,096) Source: Derived from unit level data of NSS 2009–2010. N = 136,520 jJOURNAL OF CHILDREN’S SERVICES j

- 10. casual labourer have a positive and significant effect in both models. It indicates that children belonging to these households are more likely to work in comparison to children belonging to wage labourers. Furthermore, in the case of poverty, both Rural-BPL and Urban-BPL has a positive and significant effect in comparison to Rural-APL and urban-APL in both models. This means that children from families below the poverty line in both rural and urban areas are more likely to work in comparison to children from the above poverty line. Hence, belonging to a poor household does increase the chances of the children to work. 6. Discussion and conclusion The present paper distinguishes between the “economically active children” and the “other workers” to understand the variation in the results and how the effect differs when the definition changes. This wider definition of child labour shows a higher magnitude of child labour in India. One may think that a wider definition would of course provide a higher magnitude of child labour in the country. However, the intention in using the broader definition is to get the actual figures of the working children, which are not included in the government records. Also, this wider definition helps to identify the percentage of children engaged in household work, which is not categorised as child labour. However, the present study found that they are engaged in household work without attending any educational institution, which hampers their development. They are also deprived of the leisure, which they are entitled to. As the paper deals with two different definitions of child labour, the results also came differently. However, the results have been analysed keeping in mind the socio-economic Table 5 Determinants of child labour: binary logistic regression models for India: restricted definition and expansive definition (working children = 1) Independent variables Model-1 Restricted definition Model-2 Expansive definition Men 0.45* (0.06) 0.14* (0.02) Rural 1.14* (0.21) 0.89* (0.09) Social groups ST 1.0* (0.10) 0.76* (0.05) SC 0.69* (0.09) 0.72* (0.04) OBC 0.25* 0.37* Religion (0.08) 0.03 Hindu 0.15 (0.13) 0.21* (0.07) Muslim 0.76* (0.15) 0.88* (0.07) Christian 0.80* (0.19) 0.63* (0.1) Household Size 0–4 0.26* (0.08) 0.00 (0.04) 4–6 0.25* (0.08) 0.11* (0.04) 6–8 0.47* (0.08) 0.41* (0.03) 8–10 0.48* 0.51* Household (0.10) (0.04) Type Self-nonAgri 0.43* (0.07) 0.10* (0.03) Self-agri 0.62* (0.08) 0.11* (0.04) Agri-labour 0.49* (0.10) 0.35* (0.04) Casual 0.60* 0.54* Poverty (0.13) (0.05) Rural-BPL 0.55* (0.08) 0.92* (0.04) Urban-BPL 1.44* (0.20) 1.48* (0.08) Constant 7.11* (0.24) 4.74* (0.11) N 1,447 8,151 2 Log likelihood 14,302.812a 52,107.799a Notes: Self-nonAgri = self-employed in non-agriculture. Self-Agri = self-employed in Agriculture. Agri-labour = agricultural Labour. Casual = casual labour. Rural-BPL = households below poverty line in rural areas. Urban-BPL = households below poverty line in urban areas. Rural-APL = households above the poverty line in rural areas. Reference categories: Female, Urban, General, Others, 10 and above, wage labour, Rural-APL, Urban-APL. *= Statistically significant at 0.05 or below and standard errors presented in the brackets Source: Derived from unit level data of NSS 2009–2010 jJOURNAL OF CHILDREN’S SERVICES j

- 11. paradigm that has been developed by the author and explained in the earlier paragraphs. Some of the results are not surprising given the multi-dimensional nature of the issue while others are surprising. It is not at all surprising that poverty continues to have a significant and robust effect on child labour. This reconfirms “the luxury axiom” provided by Basu and Van (1998) and tested by many others. This shows that though India is presently regarded as one of the fastest economically growing countries, its economic policies are not helping the poor people to come out from the curse of poverty, and they are still sending their children to work. Though poverty is a significant determinant, it is not the only determinant of child labour. There are other factors, which also influence the participation of children in the labour market. Given the prevalence of the caste system in India, it is not at all surprising that caste backgrounds influence the participation of children in the labour market. Empirical analysis found that children from lower-caste backgrounds (SCs, STs and OBCs, Table 3) participate more in the labour market while the children from the general category are attending educational institutions. Hence, in the Indian context, caste is a significant factor for pushing more children into labour market. The paper found no gender inequalities in child labour. However, what is interesting is that there are differences in the results concerning different definitions. In the case of only economically active children (restricted definition, Model 1), the result shows that boys are more likely to work, which is similar to the results obtained by Ray (2000). In the case of the expanded definition (Model 2), the paper found that girls are more likely to work, which conforms to the results of Roy (2013). This indicates that boys are more likely to engage in economic activities or paid jobs while girls are more likely to engage in household activities. The pattern of division of labour between boys and girls showed a similar trend as adults. As mentioned by Mishra (2014), the reason may be the stereotypical thinking that girls better handle home-based workers. There are other important factors along with the factors discussed in this paper that may have a significant impact on child labour. The socio-economic paradigm too points out that the parent’s level of education, social values, geographical conditions, also affects the incidence of child labour. Hence, child labour is a multi-dimensional issue, and one umbrella legislation is not going to solve the problem. Each dimension needs to be addressed individually and action plan should be made to deal with specific factors. However, few variables are often difficult to measure, and NSS does not capture all variables and even if some variables are present while filtering through conditions, the sample size became smaller. Also, the effect of certain variables needs to be studied using a qualitative approach such as social values and orientation of the family, which was not possible in this study due to the limitations of data used for analysis. Notes 1. Census of India collects data from Indian population on demographic, economic and social aspects and this is conducted by the Register General and Census Commissioner of India under Ministry of Home Affairs, Government of India. It collects data in every 10 years and the last census of India was done in 2011. 2. Other religions include shikh (1.7%), Buddhist (0.7%), Jain (0.4%), Other Religions and Persuasions (ORP) (0.7%) and Religion Not Stated 0.29 crores (0.2%) in the Census of India, 2011. References Agrawal, S.C. (2004), “Child labour and household characteristics in selected states: estimates from NSS 55th round”, Economic and Political Weekly, Vol. 39 No. 2, pp. 173-185. Bahar, O.S. (2014), “An overview of the risk factors that contribute to child labour in Turkey: implications for research, policy and practice”, International Social Work, Vol. 56 No. 6, pp. 688-697. Basu, K. and Van, P.H. (1998), “The economics of child labour”, The American Economic Review, Vol. 88 No. 3, pp. 412-442. jJOURNAL OF CHILDREN’S SERVICES j

- 12. Bhatty, K. (1996), “Child labour: breaking the vicious cycle”, Economic and Political Weekly, Vol. 31 No. 7, pp. 384-386. Bhukuth, A. (2008), “Defining child labour: a controversial debate”, Development in Practice, Vol. 18 No. 3, pp. 385-394. Boyden, J. and Morrow, V. (2015), “Social values and child labour”, in Fassa, A.G., Parker, D.L. and Scanlon, T.J. (Eds), Child Labour: A Public Health Perspective, Oxford University Press, pp. 1-15. Burra, N. (1995), Born to Work: child Labour in India, Oxford University Press, Delhi. Burra, N. (2005), “Crusading for children in India’s informal economy”, Economic and Political Weekly, Dec., pp. 5199-5208. Chaitanya, K. (1991), “Child labour among Digaru Mishimis of Arunchal Pradesh”, Economic and Political Weekly, Vol. 26 No. 36, pp. 2084-2085. Chamarbagwala, R. (2008), “Regional returns to education: child labour and schooling in India”, The Journal of Development Studies, Vol. 44 No. 2, pp. 233-257. Chandra, A. (2009), “A study from anthropological perspective with special reference to glass industry”, Anthropologist, Vol. 11 No. 1, pp. 15-20. Chowdhury, K. (2020), “The intersection of caste and child labour in Bihar”, Economic and Political Weekly, Vol. 55 No. 4. Dash, B.M., Prashad, L. and Dutta, M. (2018), “Demographic trends of child labour in India: implications for policy reforms”, Global Business Review, Vol. 19 No. 5, pp. 1345-1362. Deshta, S. and Deshta, K. (2000), Law and Menance of Child Labour, Anmol Publications, New Delhi. Emerson, P.M. and Knabb, S. (2006), “Opportunity, inequality and the intergenerational transmission of child labour”, Economica, Vol. 73 No. 291, pp. 413-434. Fors, H.C. (2008), “Child labour: a review of recent theory and evidence with policy implication”, Working Papers in Economics No-324, University of Gothenburg, Sweden. Government of India (2009), Right to Education Act. International Labour Organisation (2013), “Marking progress against child labour: global estimates and trends 2000-2012”, International Labour Office, Geneva. International Labour Organisation (2017), “Global estimates of child labour: results and trends, 2012- 2016”, International Labour Office, Geneva, available at: www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/@ dgreports/@dcomm/documents/publication/wcms_575499.pdf (accessed 25 November 2019). Jensen, P. and Nielsen, H.S. (1997), “Child labour or school attendance? Evidence from Zambia”, Journal of Population Economics, Vol. 10 No. 4, pp. 407-424. Kara, S. (2014), “Poverty and caste fueling child labour in South Asia”, DW:Made for Minds, October, available at: www.dw.com/en/poverty-and-caste-fueling-child-labor-in-south-asia/a-17995553. (accessed 22 February 2021). Kothari, S. (1983), “There is blood on those match sticks: child labour in Sivakasi”, Economic and Political Weekly, Vol. 27 No. 2, pp. 1191-1202. Kumar, A. (2013), “Preference based vs. market based discrimination: implications for gender differentials in child labour and schooling”, Journal of Development Economics, Vol. 105, pp. 64-68. Liebel, M. (2004), A Will of Their Own: Cross-Cultural Perspectives on Working Children, Zed Books, New York, NY. Liten, G.K. (2000), “Children, work and education-1: general parameters”, Economic and Political Weekly, Vol. 35 No. 24, pp. 2037-2043. Liten, G.K. (Ed.) (2010), “The worst form of child labour in Latin America”, Hazardous Child Labour in Latin America, Springer Media, New York, NY, pp. 1-20. Liten, G.K. (2002), “Child labour in India: disentangling essence and solutions”, Economic and Political Weekly, Vol. Dec No. 28, pp. 5190-5195. Liten, G.K. (2006a), “Child labour: the effect of public concern and neo-liberal policies”, in Satyarthi, K. and Zutshi, B. (Eds), Globalization, Development and Child Rights, Shipra Publication, Delhi, pp. 19-24. jJOURNAL OF CHILDREN’S SERVICES j

- 13. Liten, G.K. (2006b), “Child labour: what happens to the worst forms?”, Economic and Political Weekly, Vol. January, pp. 103-108. Majumdar, S. (2018), “Five facts about religion in India”, Pew Research Centre, June, available at: www. pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2018/06/29/5-facts-about-religion-in-india/ (accessed 15 February 2021). Marx, K. (1956), Economic and Philosophic Manuscript of 1844, Prometheus Books, New York, NY. Mishra, D.K. (2014), “Nimble fingers on beedis: problems of girl child labour in Sambulpur and Jharsuguda”, Indian Journal of Gender Studies, Vol. 21 No. 1, pp. 135-144. Mukerjee, R. (1945), The Indian Working Class, Hind Kitab Publishers, Bombay. Mukherjee, D. and Das, S. (2007), “Role of women in schooling and child labour: the case of urban boys in India”, Social Indicator Research, Vol. 82 No. 3, pp. 463-486. Mukherjee, D. and Das, S. (2008), “Role of parental education in schooling and child labour: urban India in the last decade”, Social Indicators Research, Vol. 89 No. 2, pp. 305-322. NCPCR Position Paper (2008), “Child labour and right to education”, National Commission for the Protection of Child Rights, available at: www.ncpcr.gov.in/view_file.php?fid=93 (accessed 22 November 2019). Orrnert, A. (2018), Evidence on Links between Child Labour and Education. K4D Helpdesk Report, Institute of Development Studies, Brighton. Ray, R. (2000), “Child labour, child schooling and their interaction with adult labour: emperical evidence from Peru and Pakistan”, The World Bank Economic Review, Vol. 14 No. 2, pp. 347-367. Remington, F. (1996), “Child labour: a global crisis without a global response”, Economic and Political Weekly, Vol. 31 No. 52, pp. 3354-3355. Roy, C. (2013), “Child rights and child development in India: a socio-economic analysis under regional perspective”, Munich Personal RePEc Archive, MPRA Paper No. 47906, available at: https://mpra.ub.uni- muenchen.de/47906/1/MPRA_paper_47906.pdf (accessed 15 February 2021). Satyarthi, K. (2006), “Development, destitution and child labour vulnerability in India”, in Satyarthi, K. and Zutshi, B. (Eds), Globalization, Development and Child Rights, Shipra Publications, Delhi, pp. 37-42. Venkateswarlu, T. (1998), “Child labour and multinational enterprises in the third world”, International Reviw of Modern Sociology, Vol. 21 No. 1, pp. 73-87. Weiner, M. (1989), “Can India end child labour?”, India International Centre Quarterly, Vol. 16 No. 4, pp. 43-50. Further reading Beteille, A. (1992), “Caste and family: in representations of Indian society”, Anthropology Today, Vol. 8 No. 1, pp. 13-18. Ministry of Labour and Employment “State-wise distribution of working children according to 1971,1981, 1991 and 2001 census in the age group 5-14 years”, Government of India, New Delhi, available at: https:// labour.gov.in/sites/default/files/Census-20012011.pdf (accessed 12 December 2019). Self, S. (2009), “Economic history of modern India”, in Hindman, H.D. (Ed.), The World of Child Labour: An Historical and Regional Survey, M.E Sharpe Inc, New York, NY, pp. 778-794. Zutshi, B. (2012), “Globalization and child labour: a case study of the carpet weaving region of Mirzapur- Bhadoi”, in Kak, S. and Pati, B. (Eds), Enslaved Innocence: Child Labour in South Asia, Primus Books, New Delhi, pp. 165-190. Corresponding author Barsa Priyadarsinee Sahoo can be contacted at: barsa2011jnu@gmail.com For instructions on how to order reprints of this article, please visit our website: www.emeraldgrouppublishing.com/licensing/reprints.htm Or contact us for further details: permissions@emeraldinsight.com jJOURNAL OF CHILDREN’S SERVICES j