India Legal - 2 March 2020

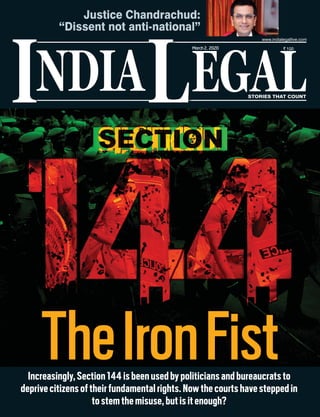

- 1. NDIA EGALL STORIES THAT COUNT I March2, 2020 TheIronFistIncreasingly,Section144isbeenusedbypoliticiansandbureaucratsto deprivecitizensoftheirfundamentalrights.Nowthecourtshavesteppedin tostemthemisuse,butisitenough? Justice Chandrachud: “Dissent not anti-national”

- 3. | INDIA LEGAL | March 2, 2020 3 he judicial postponements, mercy peti- tions and reviews in the Supreme Court and High Courts, which have delayed the hanging of the convicted rapist-murderers of Nirbhaya, have once again ignited a national controversy over the ethics, efficacy and utility of capital punish- ment as a tool of deterrence. Even as 107 coun- tries—including Russia—have done away with executions, the age-old debate about the death penalty—justice versus revenge versus deter- rence—rages on. In this context I recall a courtesy call I made in 2014 on then Chief Justice of India P Sathasi- vam who was due to retire in a week. Without referring to any specific case before him, the judge seemed highly agitated by judicial delays, particularly in the case of death row prisoners who suffer interminable mental torture or even go stark raving mad while awaiting decisions on mercy petitions. “This has to be remedied,” he said. Little did I know that a day later, a bench headed by him and comprising Justices RM Lodha, HL Dattu and SJ Mukhopadhaya would commute the death sentence of Devenderpal Singh Bhullar whose mercy petition had been pending for eight years following a 1993 Delhi bomb blast which killed nine people. The judges cited Shatrughan Chauhan vs Union of India where “unexplained and inordi- nate delays” in deciding a mercy petition as well as mental and physical illness were found valid grounds for commutation of a death sentence to life imprisonment. Sathasivam’s last judgment as CJI once again catalysed the judicial and aca- demic community to re-examine the whole death penalty issue. India Legal has tackled this subject in cover stories in the magazine as well as on its TV channel in which we featured gu- ests, including academicians from the National Law University (NLU). In 2017, an important social story that got lost in the political din of the Gujarat elections was a wide-ranging and thought-provoking report on capital punishment in India, titled “Matters of Judgment”. It is a landmark attitude study on the criminal justice system and the death penalty featuring 60 former judges of the Supreme Court of India. They include Justices AK Ganguly, Santosh Hegde, Ruma Pal, BN Srikrishna and RC Lahoti, who have adjudicated 208 death penalty cases among them between 1975 and 2016. Dr GS Bajpai, registrar and professor of cri- minology and criminal justice, a frequent guest on India Legal TV shows, said at the seminar at which the report was released: “This report is not as simplistic as we think based on its face value and has to be decoded further with respect to the observations made by the judges. It is said that criminal law is deficient. I would say that it is not that criminal law is deficient but we have failed criminal law. It is the institutions that have failed criminal law in India. Fresh insights are not being imported into the criminal law of this country. It is as if we only like to debate. This study is not the conclusion but like a hypothesis which should be taken forward by law researchers.” India Legal carried a comprehensive editorial on that report which probably has as much relevance in the context of today’s contro- versies as it did at the time when it first appeared. I reproduce below its major findings in the hope that it will create the atmosphere for a debate based on empirical data rather than pure emotion. Of the 60 former judges interviewed, 47 had adjudicated death penalty cases and confirmed 92 death sentences in 63 cases. Considering that the death penalty represents the most severe punishment permitted in law, “we sought the views of former judges on critical aspects of the criminal justice system like torture, integrity of the evidence collection process, access to legal representation and wrongful convictions,” the study’s authors said in an introduction. The interviews also examined the meaning of the EXECUTIONER’S SONG Inderjit Badhwar T Letter from the Editor IndiaLegal carried acomprehensive editorialonthe wide-rangingand thought-provoking reportoncapital punishmentinIndia, titled,“Mattersof Judgment”.The report,probably, hasasmuch relevanceinthe contextoftoday’s controversies relatedtodeath penaltyasitdidat thetimewhenit firstappeared.

- 4. 4 March 2, 2020 “rarest of rare” standard laid down by the apex court for awarding the extreme punishment in Bachan Singh vs State of Punjab, the appropriate role for aggravating and mitigating factors and the nature of judicial discretion during death penalty sentencing. The final stage of the report examines the atti- tudes of former judges to abolition or retention of the death sentence “while exploring their thou- ghts on recent developments that seek to move away from the death penalty”. T his is not the first time this troubling legal subject of life vs death has been explored in India. In the Constituent Assembly of 1947-49, it was intensely debated, with Dr BR Ambedkar staunchly opposing the death penalty. In 2015, the Law Commission headed by Justice AP Shah proposed that the country should aim at complete abolition “but as a first step that it be done away with for all crimes except terrorism. Further, the Commission sincerely hopes that the movement towards absolute abolition will be swift and irreversible”. Nonetheless, the NLU study is startling be- cause it reveals an overpowering recognition and widespread anxiety among former Supreme Court judges about India’s criminal justice system be- cause of extensive pervasiveness of torture, fabri- cation of evidence, the appalling inferiority of legal aid and unjust convictions. For example, as Dr Anup Surendranath, direc- tor of the Centre on the Death Penalty, puts it: “Judges acknowledge the misuse of Section 27 of the Evidence Act as also planting of evidence. They acknowledged that torture was a reality. Only one of them said that it does not exist. Some said that it is expected that something like that will happen. They also acknowledged wrongful convictions. But wrongful convictions were eventually pitted against wrongful acquittals by some judges and were not viewed as independ- ent problems.” Here are excerpts of the key findings and rec- ommendations of this exclusive survey: There was explicit acknowledgment and wide- spread concern about the crisis in the criminal justice system due to the use of torture to gener- ate evidence, fabrication through recovery evi- dence, a broken legal aid system and wrongful convictions. Though some former judges did offer justifications/explanations for this state of affairs, there was an overwhelming sense of concern about the integrity of the criminal justice system from multiple viewpoints. However, the grave concerns about the crimi- nal justice system did not sit quite well with the support for the death penalty. In conversations on the death penalty, the above mentioned realities of administering criminal justice in India hardly found mention. This disconnect was best demon- strated when 43 former judges acknowledged wrongful convictions as a worrying reality in In- dia’s criminal justice system generally but when it came to the death penalty, only five judges ack- nowledged the “possibility of error” as a possible reason for abolition in India. All former judges, irrespective of their position on the death penalty, were asked the reasons they saw for abolition or retention of the death penalty in India. In response, 29 former judges identified abolitionist justifications and 39 identified reten- tionist justifications. Fourteen retentionist judges took the position that there was no reason what- soever to consider abolition in India and three abolitionist judges felt there was no reason to keep the death penalty. Deterrence emerged as the strongest penologi- cal justification for retaining the death penalty, with 23 former judges seeing merit in that argu- ment. However, most of them believed that the deterrent value of the death penalty flows from a general fear of punishment rather than any particular deterrent value specific to the death penalty. The notion of a bifurcated trial, being a divi- sion between the guilt-determination phase and the sentencing phase, did not seem to hold much attraction for the former judges. Despite the sen- tencing process in death penalty cases having very specific requirements as per the judgment in Bachan Singh, the understanding of “rarest of rare” among former judges was determined/ do- minated by considerations of the brutality of the crime. For a significant number of judges, the “rarest of the rare” was based on categories or descrip- tion of offences alone and had little to do with the judicial test requiring that the alternative of life imprisonment be “unquestionably foreclosed”. This meant that for certain crimes, this widely- hailed formulation falls apart, rendering the sen- tencing exercise nugatory. Despite the law setting out an indicative list of both aggravating and mitigating circumstances to be taken into account before determining the sen- Thisisnotthefirst timethistroubling legalsubjectoflife vsdeathhasbeen exploredinIndia.In theConstituent Assemblyof 1947-49,itwas intenselydebated, with DrBR Ambedkarstaunchly opposingthe deathpenalty.In 2015,theLaw Commissionheaded byJusticeAPShah proposedthatthe countryshouldaim atcomplete abolition“butasa firststepthatitbe doneawaywith forallcrimes exceptterrorism”. Letter from the Editor

- 5. tence, there was considerable confusion about the weight and scope of mitigating circumstances. Opinions varied considerably on whether factors such as poverty, young age and post-conviction mental illness and jail conduct could be consid- ered mitigating circumstances at all, despite them being judicially recognised. A minority, in fact, did not believe in considering any mitigating cir- cumstances at all while others believed that some categories of offences were simply beyond mitigation. A striking feature, in stark contrast to the lack of confidence in the investigative process, was the confidence that judges had in discretionary pow- ers in sentencing. This was despite the fact that more than half the judges believed that the background of a judge, including their religion and personal beliefs, were factors that influenced the choice between the death penalty and life imprisonment. There appeared to be no “bright line” which distinguished judicial sentencing dis- cretion swiftly slipping into individual judge-cen- tric decisions. The law since Bachan Singh has evolved con- siderably on the issue of the scope of a sentence of life imprisonment. In December 2015, a Constitu- tion bench of the Supreme Court affirmed that it had the power to impose a sentence for a fixed duration or for the natural life of the prisoner which was beyond the scope of remission. While 25 judges believed that this sentencing formula- tion was a legally valid punishment, seven found it violative of constitutional mandate and separa- tion of powers. CONCLUSION “It is interesting that a significant number of retentionist judges identified abolitionist reason- ing. It demonstrates the inescapable force of cer- tain abolitionist arguments, but stark in its com- plete absence was any acknowledgment of the disparate impact of the death penalty on the poor and marginalised sections of Indian society. In a criminal justice system that is corrupt and violent at multiple levels, the burden on vulnerable sec- tions of society is immense, and it is only accentu- ated within the death penalty context. As such, it is peculiar as to why this aspect of the death pe- nalty in India did not find any real favour am- ongst former judges, especially those that were abolitionist. “The disproportionate representation of the poor, illiterate, and socially marginalised within the death penalty context is abundantly clear in India and other retentionist countries across the globe. The contrast between the discussions on the criminal justice system and the confidence that seems to exist in administering the death penalty in the very same system is striking. The role of harsh punishments within a crisis-ridden criminal justice system is a complex one. “The challenge really is to comprehend the considerations which drive the death penalty in a system that is plagued with torture, fabricated evidence, and wrongful convictions. As the harsh- est punishment in our legal system, the discus- sions and positions on the death penalty must feel the utmost impact of these worrying realities. It is the extreme ends of our criminal justice system, that need to be tempered by the grim reality that the former judges brought out so powerfully (in the first part of the report). “Ultimately, the fact that their concerns about the criminal justice system has not migrated to their discussion on the death penalty is indicative of the terms on which multiple competing inter- ests get balanced.” | INDIA LEGAL | March 2, 2020 5 Twitter: @indialegalmedia Website: www.indialegallive.com Contact: editor@indialegallive.com A LANDMARK STUDY The report on capital punishment featured 60 former judges of the SC. They include (from above left) Justices RC Lahoti, Santosh Hegde, Ruma Pal, BN Srikrishna and AK Ganguly. Between them, they adjudicated 208 death penalty cases between 1975 and 2016

- 6. 6 March 2, 2020 ContentsVOLUME XIII ISSUE16 MARCH2,2020 OWNED BY E. N. COMMUNICATIONS PVT. LTD. A -9, Sector-68, Gautam Buddh Nagar, NOIDA (U.P.) - 201309 Phone: +9 1-0120-2471400- 6127900 ; Fax: + 91- 0120-2471411 e-mail: editor@indialegalonline.com website: www.indialegallive.com MUMBAI: Arshie Complex, B-3 & B4, Yari Road, Versova, Andheri, Mumbai-400058 RANCHI: House No. 130/C, Vidyalaya Marg, Ashoknagar, Ranchi-834002. LUCKNOW: First floor, 21/32, A, West View, Tilak Marg, Hazratganj, Lucknow-226001. PATNA: Sukh Vihar Apartment, West Boring Canal Road, New Punaichak, Opposite Lalita Hotel, Patna-800023. ALLAHABAD: Leader Press, 9-A, Edmonston Road, Civil Lines, Allahabad-211 001. Chief Patron Justice MN Venkatachaliah Editor Inderjit Badhwar Senior Managing Editor Dilip Bobb Deputy Managing Editor Shobha John Executive Editor Ashok Damodaran Contributing Editor Ramesh Menon Deputy Editor Prabir Biswas Junior Sub-editor Nupur Dogra Art Director Anthony Lawrence Deputy Art Editor Amitava Sen Senior Visualiser Rajender Kumar Photographer Anil Shakya Photo Researcher/ Kh Manglembi Devi News Coordinator Production Pawan Kumar Group Brand Adviser Richa Pandey Mishra CFO Anand Raj Singh Sales & Marketing Tim Vaughan, K L Satish Rao, James Richard, Nimish Bhattacharya, Misa Adagini Circulation Team Mobile No: 8377009652, Landline No: 0120-612-7900 email: indialegal.enc@gmail.com PublishedbyProfBaldevRajGuptaonbehalfofENCommunicationsPvtLtd andprintedatAcmeTradexIndiaPvt.Ltd.(UnitPrintingPress),B-70,Sector-80, PhaseII,Noida-201305(U.P.). Allrightsreserved.Reproductionortranslationinany languageinwholeorinpartwithoutpermissionisprohibited.Requestsfor permissionshouldbedirectedtoENCommunicationsPvtLtd.Opinionsof writersinthemagazinearenotnecessarilyendorsedby ENCommunicationsPvtLtd.ThePublisherassumesnoresponsibilityforthe returnofunsolicitedmaterialorformateriallostordamagedintransit. AllcorrespondenceshouldbeaddressedtoENCommunicationsPvtLtd. In numerous cases, Section 144, CrPC, has been used in a draconian way by politicians and bureaucrats without holding an inquiry and deprived citizens of their fundamental rights till the courts have stepped in The Iron Fist LEAD 14 Should there be multiplicity of jurisdictional auspices in any case which can be seen as creating a conflict? An analysis by PProf Upendra Baxi A Paradigm of Labour Injustice 18 Dissent is the “safety valve” of democracy and to label it anti-national or anti-democratic strikes at the “heart” of India’s commitment to protect Constitutional values and promote deliberative democracy, Justice DY Chandrachud of the SC said recently in a speech delivered in Gujarat Dissent Not Anti-National EXCERPTS 20 MYSPACE

- 7. | INDIA LEGAL | March 2, 2020 7 Followuson Facebook.com/indialegalmedia Twitter:@indialegalmedia Website:www.indialegallive.com Contact:editor@indialegallive.com Cover Illustration & Design: ANTHONY LAWRENCE REGULARS Ringside............................8 Is That Legal.....................9 Courts.............................10 Law Campus News........12 Media Watch ..................29 International Briefs ........42 Time to be Accountable Gods Beyond Borders IT Intermediaries Guidelines (Amendment) Rules, 2018, will push for “traceability” of con- tent. But intermediaries are averse to this due to privacy and freedom of expression issues A Supreme Court bench has suggested that a former woman district judge of Madhya Pra- desh who had resigned after alleging sexual harassment by an MP High Court judge be reinstated and complimented her for her attitude 44 A proposed bill to bring in the two-child norm is in conjunction with the Constitution which says that it is the duty of the State to raise the standard of living and improve public health Too Many for Too Little GLOBALTRENDS 40 The Imran Khan government in Pakistan is expected to respond favourably to demands from Hindus for the import of idols of gods A PIL asks the top court to direct the government to release data on clinical trials of Rotovacs conducted at three test centres, for combating deaths in infants due to diarrhoea Veil of Secrecy 26 Three judges belonging to the Karnataka, Delhi and Bombay High Courts are likely to be posted to Uttarakhand, Punjab & Haryana and Meghalaya High Courts, respectively SC Collegium Recommends Transfer of Judges 28 COLUMN Despite courts consistently meting out stringent punishment to sex offenders, a lot needs to be done. A nationwide sex offender registry is one step 34The Silence of the Lambs 38 OPINION Thousands have disappeared due to repressive regimes and despite this being against international conventions, there has been little interest by governments to track them, leaving families grieving Cry, the Beloved Country 30 The Court imposed heavy fines on states and UTs which hadn’t replied to a plea to set up community kitchens to combat malnutrition Just Desserts SUPREMECOURT Grit Wins Kudos 27 24

- 8. 8 March 2, 2020 Anthony Lawrence RINGSIDE “Donald, I told you I’d guarantee you wall to wall coverage”

- 9. | INDIA LEGAL | March 2, 2020 9 ISTHAT —Compiled by Ishita Purkaystha Can a convicted rapist be refused free legal aid for exhausting his legal remedies? Article 39A in Part IV of the Constitution guarantees free legal aid to all citizens of the country, irrespective of economic or other barriers. The twin aims of the Directive Principles of State Policy enshrined in our Constitution are to secure welfare and justice to all, through social and economic democracy. Thus, despite the most heinous of offences commit- ted, every Indian citizen is entitled to representation in a court of law through legal aid. Although Part IV does not beget enforceable rights, free legal aid has been upheld by the Supreme Court as a funda- mental right under Article 21 of the Constitution. ? Ignorance of law is no excuse. Here are answers to frequently asked queries regarding matters that affect us on a day to day basis Is there a legal remedy for an employee if his employer does not pay his salary? In such cases, the employee can (i) approach the labour commissioner to reconcile the matter, or (ii) file a suit under Section 33(c) of the Industrial Disputes Act, 1947, for recovery of money due from an employer, or (iii) file a case with the com- petent authority under the Payment of Wages Act, 1936. For executives and managers earning above Rs 18,000, a summary suit under order 37 of the Code of Civil Procedure can be pursued, preferably following a legal notice to the compa- ny to clear unpaid salaries. A company may also be booked for fraud under Sec- tion 447 of the Companies Act, 2013, or under the IPC. Legal Aid for Rapists Fighting for Salary Can a Non-lawyer Argue a Case in Court? Will the electricity supply to a lawyer’s chamber within his residential premises fall under domestic consumption? Or will it be charged as per com- mercial rates? The Calcutta High Court re- cently held that electricity used by a lawyer for his chamber within his residence, though falling under the non- domestic category, yet can’t be charged under commercial (urban) rates. The Court agreed with the petitioner’s contention that the legal pro- fession, which requires a cer- tain amount of skill, cannot be called a commercial activity. It observed that a lawyer’s chamber is unlike a law firm, operating out of commercial space and dealing with both litigation and non-litigation work. Relying on an apex court precedent, the High Court asked the concerned department to supply electric- ity to the chamber at domes- tic (urban) rates. Electricity Tariffs for Lawyers Can a person who is not a lawyer appear in court on behalf of a litigant? Yes, but only subject to the prior approval of the court hearing the case. This can happen after the litigant moves a motion requesting that a non-lawyer be allowed to appear in court to argue his case. It is the court’s pre- rogative to either grant or refuse permission to a non-lawyer to appear. The apex court in a 1978 judgment held that even though a non-lawyer does not have a right to argue, he may be permitted based on his antecedents, the relationship with the litigant, cogent reasons for requisitioning the services of a private person and a variety of other circumstances as may be determined on a case to case basis. Movie Screenshot

- 10. Courts 10 March 2, 2020 The centre told the Supreme Court that the responsibility for the delay in appointing jud- ges to High Courts doesn’t lie with the govern- ment alone and that the Supreme Court Coll- egium was equally responsible. It said that while the government took, on an average, 127 days to clear a recommendation, the apex court col- legium took 119 days. Attorney General KK Venugopal (left) told a bench of Justices SK Kaul and KM Joseph that out of the 396 vacancies in the various High Courts, no recommendations had been made with respect to 199 vacancies. Taking note of Venugopal’s submissions, the top court asked the registrar generals of all High Courts to explain the vacancy position as on February 17, the day the matter was heard, and also the vacancies which would arise in the future. The bench said that registrar generals of the High Courts should also explain within four weeks the time required by them for making rec- ommendations for the vacancy of judges. Collegium too at fault for delay in appointments: Centre In a significant ruling, the Supreme Court ordered granting of permanent commis- sion to women officers in the Indian Army in all the 10 non-combat wings. “An absolute bar on women seeking criteria or command appointments would not com- port with the guarantee of equality under Article 14,” the Court said. While stating that “the absolute exclusion of women” from all command assignments, except staff assignments, is “indefensible”, the bench of Justices DY Chandrachud and Ajay Rastogi rejected the arguments against giving a greater role to women offi- cers and said that their eligibility for com- mand posts will be considered on a case- to-case basis. The bench said that “neces- sary steps for compliance with this judg- ment shall be taken within three months”. It struck down a part of the centre's February 2019 circular that had proposed permanent commission for women officers if they had not completed 14 years in service. The Court cited Captain Tania Shergill, who was the face of the Indian Army at the Republic Day parade this year, and several other women officers decorated with Seva Medals and Vishisht Seva Medals to stress that women officers brought many laurels to the nation. “To cast aspersions on women based on gender is, in fact, an affront to the entire army where men and women serve as equals,” it said. ADelhi court issued fresh death warrants against four convicts in the December 2012 Nirbhaya gang rape-cum-mur- der case, saying that deferring the death warrants would be “sacrilegious to the rights of the victim for expeditious jus- tice”. It set the date of execu- tion of the convicts—Mukesh Kumar Singh, Pawan Gupta, Vinay Kumar Sharma and Akshay Kumar—as March 3 at 6 am. The date for the hanging was rescheduled twice this year—fixed first for January 22 and then for February 1—but was rescheduled as the death row convicts had not exhaust- ed all their legal remedies. On February 5, the Delhi High Court gave the killers one week to exhaust all their legal options, after which a fresh date for hanging was to be decided. The Court also made it clear that the killers could not be hanged separately, as they were convicted of the same crime. Pawan is yet to file cur- ative and mercy petitions while Akshay wants to file a fresh mercy petition. Delhi Court orders four Nirbhaya convicts to be hanged on March 3 Give permanent commission to women in army: SC

- 11. | INDIA LEGAL | March 2, 2020 11 —Compiled by India Legal team In custody battle, child is the loser: SC Children are “always the losers” and pay the “heaviest price” in a custody battle, the Supreme Court said while asserting that the rights of the child need to be respected as he or she is entitled to the love of both parents. A bench of Justices AM Khanwilkar and Ajay Rastogi said in a judgment on a matrimonial dis- pute in which the couple was embroiled for long that the breakdown of marriage does not signify the end of “parental responsibility”. “The children are deprived of love and affection of their parents without any fault on their part,” the Court said while stating that while deciding the issue of cus- tody, the best interest of the child should be kept in mind. If efforts to settle a matrimonial dispute through the process of mediation do not fructify, then courts should make an endeavour to resolve it as expeditiously as possible because with every passing day the child pays a heavy price, the Court observed. The Supreme Court dismissed a curative petition filed by families of victims of the 1997 Uphaar cinema fire tragedy against brothers Sushil and Gopal Ansal, thus spar- ing the Ansal brothers a further jail term. A three-judge bench comprising Chief Justice of India SA Bobde and Justices NV Ramana and Arun Mishra considered the curative plea by the Association for Victims of Uphaar Tragedy (AVUT) in-chamber and dismissed it. “We have gone through the curative petitions and the rele- vant documents. In our opinion, no case is made out....Hence, the curative petition is dis- missed,” the bench said in its order. On February 9, 2017, the apex court had by a 2:1 majority verdict given relief to 78-year- old Sushil Ansal considering his “advanced age-related compli- cations” by awarding him the jail term which he had already served. It had, however, asked his younger sibling, Gopal Ansal, to serve the remaining one-year jail term in the case. Fifty-nine people died on June 13, 1997, when a fire broke out in the Ansal family-owned Uphaar theatre in south Delhi during a screening of the film Border. Judicial officers cannot be appointed district judges through direct recruitment which is reserved exclusively for practising advocates. A three-judge bench comprising Justices Arun Mishra, Vineet Saran and S Ravindra Bhat gave its verdict on the matter and held that civil judges cannot appear for the exami- nation of the higher judicial services conducted by High Courts to select Additional District Judges (ADJ). Civil judges can be appointed to the post of ADJs by promotion and not by participating in competitive examinations, Justice Mishra, who read out excerpts of the judgment, said. The higher judicial services exams can be taken by practising advocates with a minimum of seven years of experience at the bar, the court said. According to Article 233 (2) of the Constitution, a person not al- ready in the service of the Union or of a state becomes eligible for app- ointment as a district judge only if he has been an advocate or a pleader for at least seven years. No direct entry for civil judges in posts reserved for Bar SC dismisses curative plea on Uphaar fire tragedy case The Supreme Court stressed the importance of the green cover and said greenery might vanish if people don’t take seriously the issue of rapid deforestation. The Court was hearing a plea on the cutting of trees in connection with the construction of a foot over- bridge on the India-Bangladesh bor- der by the West Bengal govern- ment. The Court observed that the green cover must be preserved but people were not willing to explore alternatives. "There could be a way to create a path without cutting trees,” it added. The petition was filed by the Association for Protection of Demo- cratic Rights on the felling of over 350 trees for the construction of railway overbridges and widening of NH 112. Green cover is important, says SC

- 12. of both demographics of students at NUJS and their perform- ance in academic and extra-curricular activi- ties. In addition, information on peer behaviour and sup- port systems would also enable better evaluation.” The report is di- vided into three parts— 1) Demographics, which includes data on family, financial, linguistic background and admission category. 2) Performance of students at NUJS ac- ross academics, re- search publications and paper confer- ences; moots, de- bates, internships, pl- acements and so on. 3) Life at NUJS studying peer to peer interactions, behav- iour, support system and discrimination. Writing the foreword for the report, Kalpana Kannibiran, professor and direc- tor at the Council for Social Develop- ment, Hyderabad, cites the importance of such a study and writes, “Events between Rohith Vemula’s protest in 2015 and the movement following his death in 2016 through the death of Payal Tadvi in 2019 till the continuing present in 2020, point to the urgency of addressing ques- tions of pluralism and equality on cam- puses as the only way of building sus- tainable cultures of deliberative dem- ocracy in our contexts. It is against this backdrop that this study is extremely 12 March 2, 2020 LAW CAMPUSES / UPDATES NUJS releases Diversity Report National Law University Delhi (NLUD) in collaboration with National Human Rights Commission (NHRC) is organising a National Conference on Sexual Harassment at Workplace (Prevention, Prohibition and Redressal) Act, 2013: Issues National Conference at NLUD The West Bengal National University of Judicial Science (NUJS) has released the Diversity Report 2019. The report is a result of a year-long process conduct- ed in NUJS across five batches of stu- dents. Rohit Sharma, a student from the batch of 2020 at NUJS, conceptualised the NUJS, Diversity Report. He writes in the report that “the report is an attempt at presenting the census data collected from the students of NUJS in a proper perspective which enables both institu- tional changes in the future and individ- ual introspection in the immediate. The idea behind conducting the diversity cen- sus was to conduct a serious evaluation valuable and deeply instructive.” Presenting an interesting perspective on diversity in the campus, the report presents some interesting data like, “26.7 percent of respondents identify as Brahmin—not just general category but this caste in the general category which is the largest chunk, because ‘Other Upper Castes’ together constitute close to 32 percent. Dalits and Adivasis to- gether account for about 15.6 percent. However, the fact that within this, Adivasis are only around 5 percent is also a matter of concern especially when one correlates that with their low pres- ence in extra-curricular work, the inac- cessibility of effective peer support and ineffective mentorship to this cohort. Respondents identifying themselves as Atheists add up to 10.6 percent, not a small number, but it would be interesting to see how this cuts through caste iden- tification: Is this number drawn from the 15.2 percent who have not reported caste membership, or are they distrib- uted across caste categories? Clearly from the data on parental income, those reporting lack of knowl- edge of caste (as distinct from unwilling- ness to identify self in caste terms) belong to the most affluent families.”

- 13. | INDIA LEGAL | March 2, 2020 13 —Compiled by Nupur Dogra Law fest at College of Law, Mumbai Rajiv Gandhi National University of Law, Patiala (RGNUL) is organising the third edition of its flagship sports fest, Zelus III. Students can participate in a range of sports including tennis, badminton, basketball, athletics, table tennis, pool, snooker, chess, cricket, volleyball, and football. The sports fest will be held over March 5-8, 2020. Participants can win cash prizes up to Rs. 20,000. Thakur Ramnarayan College of Law, Mumbai hosted a two-day law fest—Lex Communique. The fest provided a platform to the student community to communicate, deliber- ate and intermingle to nurture and showcase skills. The event included moot competitions for students, a mock parliament and an experience in client counselling. The law fest is organised annual- ly to train students to analyse a problem, research the relevant law, prepare written submissions and present oral arguments thus further enhancing their reasoning ability. Sports fest at RGNUL Hidayatullah National Law University (HNLU) is hosting the fourth edition of its flag- ship event, the Inter- national Model Unit- ed Nations Confere- nce (IMUNC). The event will be held from February 28 to March 1, 2020. Through this event the university aims to inculcate debating skills and diplomacy in students. The IMUNC will have four committees mod- elled after the United Nations General Assemb- ly, the United Nations Se- curity Council, the United Nations Human Rights Council and the Lok Sabha. The students will discuss agenda like pro- tection of global climate for present and future generations of human- kind, the emerging con- flict between the US & Iran and its Global After- math, the human rights and fundamental free- doms of the people in Kashmir and so on. The students winning best delegate, high com- mendation and special mention awards will win cash prizes worth, Rs 10,000, Rs 8,000 and Rs 6,000, respectively. 3rd IMUNC at HNLU, Raipur and Challenges. The conference will have discussion on the lat- est developments around the Act. The event is scheduled on February 29, 2020 from 10 am to 4 pm. To attend the confer- ence, interested students must fill the form on the website.

- 14. 14 March 2, 2020 N February 13, the Princi- pal Bench of the Karnataka High Court struck down an order of the Bengaluru po- lice commissioner (vested with the powers of district magistrate) imposing Section 144 of the Criminal Procedure Code (CrPC) across the city during the anti-Citizenship (Amendment) Act (CAA) protests from December 19 to 21, 2019. Under this Section, a District Magistrate (DM) may “by a written order stating the material facts of the case direct any person to abstain from a certain act to prevent obstruction, annoyance or injury to any person lawfully employed, or danger to human life, health or safety, or a distur- bance of the public tranquility, or a riot, or an affray”. The High Court held that the impug- ned order was illegal and did not stand the test for exercising such an extraordi- nary power as laid down by the Sup- reme Court in Anuradha Bhasin vs. Union of India. These tests are: The danger contemplated for impos- ing Section 144, CrPC should be in the nature of an “emergency”. This power cannot be used to sup- press legitimate expression of opinion or grievance or exercise of any demo- cratic rights. An order passed under this Section should state the material facts to enable a judicial review of the same. The power should be exercised in a bona fide and reasonable manner, and the same should be passed by relying on the ma- terial facts, indicative of application of mind. While exercising the power under this Section, the magistrate is duty-bound to balance the rights and restrictions based on the principles of proportionality and thereafter apply the least intrusive The Iron Fist Inmanycases,ithasbeenusedinadraconianwaybypoliticiansandbureaucratswithout holdinganinquiryanddeprivedcitizensoftheirfundamentalrightstillthecourtssteppedin Lead/ Section 144, CrPC MG Devasahayam O SUPPRESSING RIGHTS Historian Ramachandra Guha was detained by the Bengaluru City Police for violating Section 144 Photos: UNI

- 15. | INDIA LEGAL | March 2, 2020 15 measure. Repetitive orders under this Section would be abuse of power. The High Court acknowledged the necessity of these conditionalities be- cause a prohibitory order under Section 144 has a chilling and terrifying effect on the citizens by depriving them of their fundamental rights, particularly Article 19 (assembling peacefully and without arms and practising or carrying on any occupation, trade or business) and Article 21 (life or personal liberty). Such a promulgation lets loose a chain of criminal liabilities on those partici- pating in any assembly which has been declared unlawful even if peaceful. They commit cognisable offence and under Section 151 of the CrPC, a police officer has powers to arrest without a warrant any person who has a design to partici- pate in unlawful assembly. Such partici- pation attracts several Sections, 143, 145, 146, 147, 149, 150 and 151, of the Indian Penal Code (IPC), some of which are punishable with two years’ rigorous imprisonment, even for innocent, unarmed men, women and children. In view of the enormity of an order under Section 144, the DM should be extremely careful and fully satisfied that there is sufficient ground for proceeding under this Section. An order passed when there is no “emergency” is without jurisdiction. And before proceeding under this Section, the magistrate should hold an inquiry and record the urgency of the matter. For the purposes of Section 144, it is only the magistrate issuing the order who should believe that apprehension of nuisance or danger exists. This is a subjective satisfaction based on the information, intelligence reports and other material that have been brought to his notice. No order can be passed under this Section on the complaint/representation of any party. Neither can anybody—High Court, gov- ernment or police—goad the magistrate into it. B ut of late, such essential require- ments are more observed in the breach than compliance. A typi- cal example is the Section 144 order promulgated at Tuticorin in Tamil Nadu on May 21, 2018, which led to an ex- treme form of police repression that claimed the lives of 13 people and the limbs of many more. For years, people of this small port town have been waging a struggle against Vedanta Limited’s Co- pper Smelter Plant (Sterlite, which is a subsidiary of Sterlite Industries, a com- pany owned by Vedanta) which has been poisoning the water they drink and the air they breathe. In their arrogance, this private entity demanded the DM impose Section 144 to protect their personnel, plant and machinery. When the DM did not oblige, they moved the Madurai Bench of the Madras High Court for a writ of mandamus to direct the DM to do so. Surprisingly, without jurisdiction, a High Court judge determined, based on a pamphlet supplied by the offending party, that there would be a serious law and order situation and therefore Section 144 should be imposed in Tuti- corin or the DM would be guilty of “de- reliction of duty” and the “Court would be justified in invoking its powers under Article 226 of the Constitution”. On re- ceipt of this order, the superintendent of police of the district wrote a letter to the DM on May 21 virtually dictating the Section 144 order as it was pronounced later. This is just not permissible. In the meantime, Tuticorin was con- verted into a fortress with a formidable police force comprising an additional director general of police, four inspector generals, two deputy inspector generals, 15 SPs and scores of additional SPs, deputy SPs and about 3,000 police per- sonnel along with squads of comman- dos. Sure enough, the “prohibitory order” issued by the DM abiding by the High Court diktat and the SP’s recom- mendation brought ruthless “Police Raj” repercussions seen in the “massacre of innocents” the next day, ie, on May 22, 2018. On that day, one saw terrifying visuals of trained sharp-shooters per- ched on a police van and public building shooting unarmed “protesters” with self- loading, semi-automatic rifles with the pronounced intention (heard over audio) to kill. All this was done to pander to the wishes of an MNC. This was acknowl- edged by the Sterlite Copper CEO, P Ramnath, on the day of the massacre: “I totally regret what happened today. It was totally uncalled for and is really unfortunate. We had, in fact, taken all the precautionary steps by getting the court order for Section 144.... Although TheSection144orderpromulgatedat TuticorininTamilNaduonMay21,2018, ledtoanextremeformofpolicerepres- sionthatclaimedthelivesof13people andthelimbsofmanymore.

- 16. Lead/ Section 144, CrPC/ MG Devasahayam 16 March 2, 2020 we expected it to be peaceful given Section 144 and considering the efforts made by the police and the collectorate.” Thus Section 144 was used as a phys- ical weapon against democratic voices. Now, the Moradabad district adminis- tration in UP is using this Section as a financial weapon by slapping Imran Pratapgarhi, a poet-politician, with a fine of Rs 1.04 crore “for violating Section 144” by participating in an anti- CAA protest. A notice issued by the additional DM-City asking him to pay said: “One company of Rapid Action Force and a half section of Provincial Armed Constabulary have been dep- loyed at the protest site. It amounts to a total expenditure of Rs 13.42 lakh per day...the total sum spent on security amounts to Rs 1,04,08,693.” What a way to protect the fundamental right of freedom of speech and assembly! I n the police commissionerate sys- tem, things are worse. Take the example of Chennai metropolis. In an autocratic manner, the Chennai po- lice insist that citizens should get “per- mission” to perform even basic demo- cratic rights and duties. The mere men- tion of a mild protest sends them into a tailspin, and a posse of police person- nel much larger than the “protesters” is deployed to intimidate them. More often, their attitude is menacing and arrest/detention without any charge has become routine. Even women are not spared and ladies drawing kolam in front of their homes are detained. The Chennai City Police is doing all this by grossly abusing/misusing Section 41 of the Madras City Police (MCP) Act, 1888, an anachronistic and archaic colo- nial legislation meant to ruthlessly crush any protest or dissent against British rule. By no stretch of imagination can this be relevant in free India. Sub-Sec- tion 41(1) of the MCP Act does not obli- gate citizens to seek “permission” from the police for conducting any assembly or meeting in a public place. And cer- tainly not in a private place or hall. The Section only authorises the police com- missioner to regulate. It does not give him any powers to “prohibit” or “pre- vent” any assembly. Such power is found only under Sub-Section 41(2): “… Commissioner may, by order in writing, prohibit any assembly, meeting or pro- cession if he considers such prohibition to be necessary for the preservation of public peace or safety.” This sub-section is redundant and should have been scrapped as soon as the Code of Criminal Procedure was enacted by Parliament in 1973 incorpo- rating Section 144 which gives this po- wer and authority to DMs. As we have seen, the prohibitory order is draconian. But it has built-in checks and balances and clear Supreme Court guidelines. But Sub-Section 41(2) of the MCP Act has none and by applying this on a non-stop basis, the police become dictatorial. As the Chennai police chief is vested with police and magisterial powers under the MCP Act and CrPC, respectively, this is a “double jeopardy” for citizens, with the commissioner acting as super-cop and magistrate. Democracy and fundamental rights are being routinely jeopardised by abus- ing legal provisions meant only for em- ergency situations. Politicians wanting to hold on to power and carpetbaggers amassing wealth may want it. Should civil servants who have sworn to uphold democracy and fundamental rights be party to this? The jury is out on this. —The writer is a former Army & IAS officer TheMoradabaddistrictadministrationis usingSection144asafinancialweapon byslappingImranPratapgarhiwithafine ofRs1.04crore“forviolatingSection 144”byattendingananti-CAAprotest. Twitter.com NO RULE OF LAW A protest being quelled by the Chennai police who often arrest or detain people without any charge

- 18. My Space/ Contract Labour Prof Upendra Baxi 18 March 2, 2020 HE practice by a two judge-bench in referring issues to a larger bench has been institutionalised to perfection by the apex court. Surely, when deci- sions of a two-judge bench conflict inter se, it is often thought prudent to refer the matter to the chief justice of India (CJI) to constitute a larger bench which should decide the binding law under Article 141. Legal certainty is here con- sidered integral to doing of justice. It is on this understanding that justices and legal professionals have achieved trans- actions of certainty in law. Future courts may tell us whether or not this produces legal certainty; the referring benches seem certainly to hope that this will be the case. Not all decisions, even when seem- ingly at conflict, are referred to a lager bench. In the case referred to—Krishna Gopal (February 9, 2020) which referred the entire matter to the CJI to convene a larger bench—the referring bench cites a decision of Justice AK Sikri that seeks to apply the doctrine of harmonious construction in situations of conflicting opinion (Para 21). However, the justice effects of refer- ence to a larger bench provide some normative standards by which this is warranted. Such standards are scarcely exhausted by mere reference to conflict- ing decisions of two-judge benches but by reference to the contexts of different decisions in the same domain. Different statutory auspices render unjust any one-size-fits-all reference to a larger bench. Much would here depend though on how Article 32 guarantees enforcement of constitutional rights— seen as lying only within the power of the Court or accompanied with the duty to provide constitutional justice. Justices Dr Dhananjaya Y Chand- rachud and Ajay Rastogi in Krishna Gopal (in the dispute between tempo- rary workmen and ONGC) requested the learned chief justice to constitute an appropriate bench to reconsider the decision in PCLU (2015). That decision needed reconsideration about the inter- pretation “placed on the provisions of clause 2(ii) of the Certified Standing Orders”; “the meaning and content of an unfair labour practice” under the Fifth Schedule of the Industrial Disputes Act and “the limitations, if any, on the power of the Labour and Industrial Courts to order regularisation in the absence of sanctioned posts”. Prima facie, the reference seems jus- tified but one ought to ascertain from the referring order whether the conflict among the two-judge benches justly warrants it. It is triggered primarily by the PCLU (Oil and Natural Gas Corp- oration Limited v Petroleum Coal Labour Union, 2015), which is a quar- Shouldtherebeamultiplicity ofjurisdictionalauspices whichcanbeseenascreating aconflictinanycase? A Paradigm of Labour Injustice? T LABOUR RIGHTS Coal Workers’ Federation protests in Asansol

- 19. | INDIA LEGAL | March 2, 2020 19 ter-century-old saga of the battle of legal wits between the management and the workmen! All the courts before the apex court had already ordered the regulari- sation of the temporary employees. Justice V Gopala Gowda (speaking also for Justice C Nagappan) upheld the validity of the Industrial Employment (Standing Orders) Act, 1994. This order cannot be overcome by any company policy, for to do so would be to abandon the “sunny” days belief that the “eco- nomic law of demand and supply in the labour market would settle a beneficial bargain”—at law “they venerated as nat- ural law” (Para 33). One hopes that the indictment of per incuriam does not extend so far as to invalidate this noble belief! The referring bench states that the PCLU decision is not “prima facie cor- rect”. Why so? Because it feels that the decision goes too far in ruling that “the workmen upon completion of 240 days service in a period of 12 calendar mon- ths … are entitled for regularisation of their services into permanent posts of the corporation” or that they have acquired a “valid statutory right” (Para 17). But the referring bench does not consider fully the argument that acting otherwise is unconstitutional and illegal because “the corporation which is an instrumen- tality of the State under Article 12 cannot act arbitrarily or unreason- ably”. On the facts of the case here, that action of the corporation cannot but be considered (in the later phrase—regime of Justices Rohinton Nariman and Dhana- njaya Chandrachud (Kantaru Rajeevaru, 2019) as “manifestly arbitrary”. Similarly, it is not quite clear why the referring bench should not agree with decisions of coordinate benches which upheld the powers of industrial and labour courts in passing appropriate orders. In Uma Devi (2006), it has rightly been held by the apex court as applying only to High Courts and the Supreme Court; it does not oust the per- tinent provisions in either the standing orders or of the Industrial Disputes Act. Nor do the other decisions concerning reemployment on retrenchment or cre- ation of new posts (which is rightly held as lying within the competence of the executive) seem relevant to warrant a reference. M ore startling is the observa- tion regarding what may con- stitute an unfair labour prac- tice. No doubt, “under Section 2(ra) read with Item 10 of the Vth Schedule of the ID Act, the employer should be engaging workmen as badlis, tempo- raries or casuals, and continuing them for years, with the object of depriving them of the benefits payable to perma- nent workmen”. The opinion written by Justice Chandrachud virtually underscores the last 13 words. But surely these words are capable of an alternate interpreta- tion which would suggest that the “object of depriving” the workers of the “benefits payable of permanent work- men” may be gathered implicitly or explicitly. That is, discrimination against such employees may be writ large or it may also be gathered from a course of conduct. Moreover, Durgapur Casual Workers (2014) could have thrown adequate light on the scope of Umadevi. Justices Sudh- ashu Jyoti Mukhopadhyaya (with Jus- tice Prafulla C Pant) maintain that it is an authoritative pronouncement for the proposition that the Supreme Court (Article 32) and High Courts (Article 226) should not issue “directions of absorption, regularisation or permanent continuance of temporary, contractual, casual, daily wage or ad hoc employees unless the recruitment itself was made regularly in terms of the constitutional scheme”. But it does not “denude the Industrial and Labour Courts of their statutory power” to “order permanency of the workers who have been victims of unfair labour practice on the part of the employer”, when the “posts on which they have been working exist”. The referring bench sees a conflict in this holding; but is it illegitimate to ask why multiplicity of jurisdictional aus- pices by itself be seen as creating a con- flict? Should Article 32 and 226 furnish the sole jurisdiction for all disputes on regularisation, regardless of other statu- tory auspices? We must finally note that in almost all the situations, detailed in this refer- ence, the workmen involved were con- tract labourers asking for regularisation from state-owned statutory corporations who had continued their employment for very long periods of time. This practice has grown rampant, despite clear statutory intention to the contrary. Doing of justice required that the Court respected this intention of creating an implied statutory right rather than refer the matter to a larger bench. —The author is an internationally renowned law scholar, an acclaimed teacher and a well-known writer JusticesDrDhananjayaYChandrachudandAjay Rastogi(right)inKrishnaGopal (inthedispute betweentemporaryworkmenandONGC)requested thechiefjusticetoconstituteanappropriatebench toreconsiderthedecisioninPCLU(2015).

- 20. Excerpts/ Justice PD Desai Memorial Lecture 2020 20 March 2, 2020 N occasions such as this when a lecture series co- mmemorates the memory of a distinguished person- ality, it is conventional to begin with words of trib- ute. But for me personally, the opportu- nity to speak on this occasion has a deep personal connect. For me, this is a hom- age to the Master. Justice Prabodh Dinkarrao Desai had the unique distinction of being ap- pointed as a Judge of the High Court of Gujarat when he was barely thirty-nine. Over a distinguished career, he func- tioned as the Chief Justice of three High Courts in succession, those of Himachal Pradesh, Calcutta and Bombay between December 1983 and December 1992. That a person who was appointed as a Judge of the High Court so young and yet was overlooked by destiny or the powers that be (whichever way one looks at it), must remain in contempo- rary times as another aberration in the process of judicial appointments. When the call for higher judicial office came, Chief Justice PD Desai preferred to retire from the Bombay High Court: so fiercely was he protective of his own independence and integrity.... India as a whole, boasts of significant diversity—heterogeneous along a num- ber of intersecting dimensions, includ- ing race, class, religion, and culture. This diversity is further defined across several axes: cultural, social, and epis- temic and outlays diverse values, opin- ions, and perspectives.…In the plural mansion that is independent India, lies a population of over 1.3 billion people comprising several thousand communi- ties. At the framing of the Indian Co- nstitution, questions arose on how ind- ependent India was to account for its heterogeneous polity. Uday Mehta elo- quently elucidates the immense range of social realities that the founding mem- bers were called upon to address and how the document they gave birth to sought to unify a divergent India by accommodating all people who called India their home. For the founders, the Dissent Not Anti-national Dissentisthe“safetyvalve”ofdemocracyandtolabelitanti- nationaloranti-democraticstrikesatthe“heart”ofIndia’s commitmenttoprotectConstitutionalvaluesandpromote deliberativedemocracy,JusticeDYChandrachudofthe SupremeCourtsaidrecently.Excerptsfromhisspeech: O

- 21. | INDIA LEGAL | March 2, 2020 21 Constitution was premised on both a deep trust in the tolerant nature of its citizens and an unshakeable belief that our diversity would be a source of strength. As Mehta observes, where the population was largely illiterate, the Constitution conferred universal adult franchise. Where the population was diverse and assorted, the Constitution conferred citizenship without regard to race, caste, religion or creed. Where the people were deeply religious, the Constitution adopted the principle of secularism. Where the Indian State stood united, the Constitution created a federal democracy with all the political instruments necessary for local self-gov- ernance. Diversity within the strands of the Constitution is a reflection of the diversity of her people. One cannot exist without the other…. T he Constitution enacted a com- plete ban on untouchability and its practice in any form. The Constitution also stipulates that no citi- zen is to be subject to any disability or condition with regard to access to public spaces and the use of public resources on the grounds of religion, race, caste, sex, or place of birth and that the state is empowered to legislate special provi- sions for the advancement of any social- ly and educationally backward class of citizens…. In elevating groups as distinct rights holders as well as empowering state intervention to address historical injustice and inequality perpetrated by group membership, the framers located liberalism within the pluralist reality of India and conceptualised every individ- ual as located at an intersection between liberal individualism and plural belonging…. The true test of a democracy is its ability to ensure the creation and pro- tection of spaces where every individual can voice their opinion without the fear of retribution. Inherent in the liberal promise of the Constitution is a commit- ment to plurality of opinions. However, the litmus test of any claim of commit- ment to deliberation is assessed by the response of two key actors—the state and other individuals. If you wish to deliberate you must be willing to hear all sides to the story. A legitimate gov- ernment committed to deliberate dia- logue does not seek to restrict political contestation but welcomes it. As early as the 19th century, Raja Ram Mohan Roy protested against the curtailing of the press and argued that a state must be responsive to individuals and make available to them the means by which they may safely communicate their views. This claim is of equal rele- vance today. The commitment to civil liberty flows directly from the manner in which the State treats dissent. A state committed to the rule of law ensures that the state apparatus is not employed to curb legitimate and peaceful protest but to create spaces conducive for delib- eration. Within the bounds of law, liber- al democracies ensure that their citizens enjoy the right to express their views in every conceivable manner, including the right to protest and express dissent against prevailing laws. The blanket India,committedtopluralism,isnotone language,onereligion,onecultureorone assimilatedrace.TheConstitutionpro- tectstheideaofIndiaasarefugetopeo- pleofvariousfaiths,racesandbeliefs. UNI

- 22. 22 March 2, 2020 Excerpts/ Justice PD Desai Memorial Lecture 2020 labelling of such dissent as anti-national or anti-democratic strikes at the heart of our commitment to the protection of co- nstitutional values and the promotion of a deliberative democracy. Protecting dis- sent is but a reminder that while demo- cratically elected governments offer us a legitimate tool for development and so- cial coordination, they can never claim a monopoly over the values and identities that define our plural society. The employment of state machinery to curb dissent instills fear and creates a chilling atmosphere for free speech which violates the rule of law and de- tracts from the constitutional vision of a pluralist society. T he destruction of spaces for ques- tions and dissent destroys the ba- sis of all growth—political, eco- nomic, cultural and social. In this sense, dissent is the safety valve of democracy. The silencing of dissent and the genera- tion of fear in the minds of people go beyond the violation of personal liberty and a commitment to constitutional val- ues—it strikes at the heart of a dialogue- based democratic society which accords to every individual equal respect and consideration. A commitment to plural- ism requires positive action in the form of social arrangements where the goal is—to incorporate difference, coexist with it, allow it a share of social space. There is thus a positive obligation on the state to ensure the deployment of its machinery to protect the freedom of ex- pression within the bounds of law and dismantle any attempt by individuals or other actors to instil fear or chill free speech. This includes not just protecting free speech, but actively welcoming and encouraging it. An equal obligation to thwart at- tempts to curtail diverse opinions rests on every individual who may not agree with opposing views. Mutual respect and the protection of a space for diver- gent opinions is the process of viewing every individual as an equal member of a shared political community where membership is not premised on sharing a unanimous opinion…. Taking democ- racy seriously requires us to respond respectfully to the intelligence of others and participate vigorously—but as an equal—in determining how we should live together. Democracy then is judged not just by the institutions that formally exist but by the extent to which different voices from diverse sec- tions of the people can actually be heard, re- spected and accounted for. The great threat of pluralism is the suppres- sion of difference and the silencing of popular and unpopular voices offering alternate or opposing views. Suppression of intellect is the suppression of the conscience of the nation. This brings me to the second threat to pluralism—the belief that homogeni- sation presupposes the unity of the na- tion…. As I have stated before, the fra- mers demonstrated a commitment for the protection of India’s pluralist str- ands. For this reason, amendments to delete the right to propagate religion and to include a ban on dressing that identified with a religion were negatived in the Constituent Assembly. By negating these amendments, the Constituent Assembly asserted the place of plural expression in the public sphere and signalled a clear departure from the singular unification model. Similarly, even though it was unanimously agreed that the freedom to propagate religion was included within the freedom of speech, the assembly found it necessary to include a specific provision in Article 25 also stating that a heavy responsibili- ty would be cast on the majority to see that minorities feel secure. A united India is not one charac- terised by a single identity devoid of its rich plurality, both of cultures and of values. National unity denotes a shared culture of values and a commitment to RIGHT TO DISSENT Lawyers (left) protesting against the CAA, the NRC and the police repression Anil Shakya

- 23. | INDIA LEGAL | March 2, 2020 23 the fundamental ideals of the Constitu- tion in which all individuals are guaran- teed not just the fundamental rights but also conditions for their free and safe exercise. Pluralism depicts not merely a commitment to the preserva- tion of diversity, but a commitment to the fundamental postulates of individual and equal dignity. In the creation of the imagined polit- ical community‘ that is India, it must be remembered that the very concept of a nation state changed from hierarchical communities to networks consisting of free and equal individuals. India, as a nation committed to plu- ralism, is not one language, one religion, one culture or one assimilated race. The defence for pluralism traverses beyond a commitment to the text and vision of the Constitution‘s immediate beneficiar- ies, the citizens. It underlines a commit- ment to protect the very idea of India as a refuge to people of various faiths, races, languages, and beliefs. India finds itself in its defence of plu- ral views and its multitude of cultures. In providing safe spaces for a multitude of cultures and the free expression of diversity and dissent, we reaffirm our commitment to the idea that the making of our nation is a continuous process of deliberation and belongs to every indi- vidual. No single individual or institu- tion can claim a monopoly over the idea of India…. Finally, the commitment to pluralism lies in the constitutional trust expressed by the framers on every individual.… An example of this constitutional trust and obligation is evident in the divergent view of the relations between majorities and minorities upon India gaining her independence. During the colonial rule, the Morley- Minto reforms recommended separate electorates for minorities. This recom- mendation for the first time introduced identity politics into the Indian regime by classifying groups as majority and minority.… When the Constituent Assembly was called to decide the fate of separate electorates in independent India, they decided that its inclusion was not essential to and even contrary to the requirements of a pluralistic soci- ety. They rejected separate electorates and dismissed the relevance of numeri- cal disadvantage in a polity…. The framers of the Constitution rejected the notion of a Hindu India and a Muslim India. They recognised only the Republic of India. As one member of the Constituent Assembly said—we should proceed towards a compact nation, not divided into different com- partments but one where every sign of separatism should go. As another mem- ber said—there will be no divisions amongst Indians. United we stand; divided we fall.... What is of utmost relevance today, is our ability and commitment to preserve, conserve and build on the rich pluralist history we have inherited. Homogeneity is not the defining feature of Indians. MA Kalam, a celebrated anthropologist wrote in a piece that: “a visible, dis- cernible, lively and successful engage- ment with diversity, is pluralism indeed. This definition calls upon us to look at each other and recognise that our differ- ences are not our weakness.” Our ability to transcend these differ- ences in recognition of our shared hu- manity is the source of our strength. Pluralism should thrive not only because it inheres in the vision of the Constitution, but also because of its inherent value in nation building. T oday I have attempted to share with you the vision and spirit of pluralism that I believe has always defined India. India is a sub-con- tinent of diversity unto itself. The mere mention of India evokes in every person a different idea which they associate with the nation. Anybody truly conversant with Indian history will tell you that the sin- gle defining hallmark of ancient India was its divergent, scattered and frag- mented nature. It has been for centuries a land of vibrant diversity of religion, language and culture. Pluralism has already achieved its greatest triumph—the existence of India. The creation of a single nation out of these divergent and fragmented str- ands of culture in the face of colonial tyranny is a testament to the shared humanity that every Indian sees in every other Indian. The nation’s continued survival shows us that our desire for a shared pursuit of happiness outweighs the dif- ferences in the colour of our skin, the languages we speak or the name we give the Almighty. These are but the hues that make India and taking a step back we see how altogether they form a kaleidoscope of human compassion and love surpass- ing any singular, static vision of India. Pluralism is not the toleration of diversi- ty; it is its celebration. TheConstitutionwaspremisedonanun- shakablebeliefthatourdiversitywould beasourceofstrength.Diversitywithin thestrandsoftheIndianConstitutionisa reflectionofthediversityofherpeople.

- 24. Supreme Court/ Community Kitchens 24 March 2, 2020 Supreme Court bench on February 17 slapped an additional fine of Rs five lakh on Maharashtra, Delhi, Manipur, Odisha and Goa for not filing counter-affidavits to a plea seeking the setting up of pan-India community kitchens. This makes the overall fine payable by each state Rs ten lakh. The bench, headed by Justice NV Ramana, also refused to waive the fine, as requested by several states. The attor- ney general, representing the centre, said an affidavit had already been filed and another would be filed soon with respect to the scheme. On February 10, a bench headed by Justice Ramana observed that only seven states and Union Territories (UTs) had filed affidavits. These are: Andaman and Nicobar Islands, Punjab, Karna- taka, Uttarakhand, Jharkhand, Naga- land and Jammu and Kashmir. The bench ordered that Rs one lakh be imposed on states which had failed to submit their replies but were filing it within 24 hours and Rs five lakh on those which had failed to submit their replies even after 24 hours. The fines were imposed for non- compliance with a September 2, 2019, order which had directed them to file their replies. Petitioners Anun Dhawan, Ishann Dhawan and Kunjan Singh told the apex court that the “Right to Food” was a fundamental right which was well- recognised under national and interna- tional laws as it protects the right of people to access food and feed them- selves. They said that the right to food is interlinked with the right to life and dig- nity as envisaged in Article 21 of the Constitution and therefore, it requires that food be available, accessible and adequate for everyone without discrimi- nation or inequality. The lack of accessi- bility of food with adequate amount of nutrition would be a gross violation of Articles 14, 21, 38, 39, 47 and 51(c) of the Constitution. They contended that the Supreme Court from time to time had held that the right to life includes the right to live with dignity and all those basic rights which go along with it, including the right to food. The petitioners also cited several important cases including Francis Coralie v. Union Territory of Delhi and Paramanda Katara v. Union of India. Strong reliance was also placed on the judgment delivered by Justice PN Bhagwati in Kishen Pattayanak and Ors. v. State of Orissa, wherein it was held: “No one in this Country can be allowed to suffer deprivation and exploitation particularly when social justice is the watchword of our constitution.” The petitioners also mentioned Peo- ple’s Union for Civil Liberties v. Union of India & Ors, 2013, wherein the apex court had directed all states and UTs to implement various food-related schemes. Reference was also made to state- Just Desserts TheCourtimposedheavyfinesonstatesandUTs whichhadn’trepliedtoapleatosetupcommunity kitchenstocombatmalnutrition By Ananthu Suresh A ThebenchheadedbyJusticeNVRamana refusedtowaivethefine,asrequestedby severalstates.Thebenchobservedthat onlysevenstatesandUnionTerritories hadfiledaffidavits.

- 25. | INDIA LEGAL | March 2, 2020 25 funded community kitchens being run in Tamil Nadu (Amma Unavagam), Rajasthan (Annapurna Rasoi), Andhra Pradesh (Anna Canteen), Karnataka (Indira Canteen), Odisha (Ahaar Centre), Jharkhand (Mukhyamantri Dal Bhat) and Delhi (Aam Aadmi Canteen) which serve meals at subsidised rates under hygienic conditions. They contended that all these com- munity kitchens were established with the object of combating hunger and malnutrition in India. They said that “the rationale behind Amma Unavagam scheme is akin to soup kitchen of the US and Europe to feed the poor by serving a limited menu of nutritious cooked food at below the market price”. These soup kitchens are staffed by voluntary organi- sations from churches or community groups. They further said that these state-funded community kitchens would not only combat chronic hunger and malnutrition problems in India but would be a great tool to provide employ- ment as well. One of the suggestions of the peti- tioners was that such community kitchens could be managed either with state funding or public-private partner- ship with funding a part of corporate social responsibility. T he petitioners also relied on sev- eral reports to show that malnu- trition and hunger were soaring at an alarming rate in the country. The petition stated that “it has been reported in 2017, by the National Health Survey (NHS) that approximately 19 crore peo- ple in the country are compelled to sleep on empty stomach, every night. Moreover, the most alarming figure revealed is that approximately 4,500 children die every day under the age of 5 years in our country resulting from hunger and malnutrition, amounting to over 3 lakh deaths every year owing to hunger of children alone. Additionally, it has been reported that 7,000 persons (including children) die of hunger every day and over 25 lakh persons (including children) die of hunger annually”. The Global Hunger Index 2018 report prepared by Concern Worldwide and Welthungerhilfe ranked India at 103 out of 119 countries. India scored 31.1, indicating that it suffers from a level of hunger that is critical and seri- ous. In addition, the Food and Agriculture Report, 2018 stated that India houses 195.9 million of the 821 million undernourished people in the world, accounting for approximately 24 percent of the world’s hungry. They said that in spite of having a plethora of schemes and programmes to eradicate the issues pertaining to hun- ger, malnutrition and food security, the desired result was a distant reality. This is because these schemes were ridden with problems and the country was still grappling with them on a large scale. Their plea to the Supreme Court was: To direct the chief secretaries of all states and UTs to formulate a scheme for the implementation of community kitchens and to further ensure that no person sleeps on an empty stomach. To direct the National Legal Services Authority to formulate a scheme to fur- ther the provisions of Article 51A of the Constitution in order to mitigate deaths resulting from hunger, malnutrition and starvation. To direct the central government to create a national food grid for those beyond the scope of the public distribu- tion scheme. The matter is listed for further hear- ing on April 8. FOOD FOR ALL A community kitchen in Patna

- 26. Supreme Court/ Rotovac Clinical Trial 26 March 2, 2020 Y withholding data on clini- cal trials of a vaccine con- ducted on infants to combat death caused by diarrhoea, the government is infring- ing upon the fundamental rights of people under Articles 14 and 21 of the Constitution. This was the gist of a petition filed in the Supreme Court to bring into the public domain the data related to clinical trials conducted on 6,799 infants of Rotavirus vaccine which was launched by the health ministry. Last week, when the matter came before a bench of Justice Arun Mishra, the Court asked the government to submit documents about guidelines framed by the Indian Council of Medical Research (ICMR) in Novem- ber last year relating to the research on the vaccine. The vaccine, Rotavirus, developed by Hyderabad-based Bharat Biotech, was launched in March 2015 after getting government approval following clinical trials to gauge its efficacy and safety. The trials were conducted at three centres— Delhi, Pune and Vellore—to measure the safety and effectiveness of the vaccine. The duration of the trial was two years within which the infants were adminis- tered the vaccine and its safety was me- asured according to the number of intus- susceptions. Intussusceptions are intes- tinal obstructions that may need an ur- gent surgery to prevent death among in- fants and can be diagnosed by ultraso- und examination. After studying the aggregate data of all three centres, an expert member of the National Technical Advisory Group on Immunization—the apex advisory body of the government on immunisa- tion, deduced that the number of cases of intussusceptions in the infants from the Vellore centre was the highest and there was a huge difference in the num- ber of cases of intussusceptions in Delhi and Vellore. The issue was also raised by a UK medical journal which, after a study of the aggregated results of these clinical trials, raised certain questions about the efficiency of the vaccine and various risks associated with it. Consequently, it was decided that de- tails regarding centre-wise data be ob- tained in order to gauge the efficacy and also to ascertain whether a certain sec- tion of the population is more suscepti- ble to adverse effects of the vaccine than others and whether it is safe in all areas or if people of some specific areas are more likely to be harmed by it. In fact, the rationale behind conducting multi- centre trials was precisely this. But despite several RTI requests, the government has thrown a veil of secrecy over the relevant data. Letters were dis- patched to the Prime Minister’s Office which in turn is said to have asked the Subject Experts’ Committee to look into the data from Vellore. Even that order has not been complied with, despite being aware that not providing complete results of clinical trials involving human beings is a violation of the ethics of med- ical research and global norms which govern clinical trials. Also, such conceal- ment will cause injustice to the thou- sands of infants who participated in this study, to the researchers and to the med- ical/scientific community. In fact, it is all the more crucial to study the segregated data because the government has now launched the vac- cine in four different states. A large number of infants might be adminis- tered the vaccine in these states. It would thus be highly unethical to proceed with immunisation without informing the public of the risks and adverse effects associated with the vaccine. The PIL filed in 2016 in the Delhi High Court will come up for hearing in the apex court next week. Veil of Secrecy APILaskstheSupremeCourttodirectthegovernmentto releasedataonclinicaltrialsofRotovac,conductedatthree testcentres,forcombatingdeathsininfantsduetodiarrhoea By Simran Singh B FIGHTING INFANT MORTALITY The oral Rotavirus vaccine being adminis- tered to an infant to reduce risk of diarrhoea uib.no