Running head ARTIFACT ANALYSIS WORKSHEET 1 1Artifact Analys.docx

- 1. Running head: ARTIFACT ANALYSIS WORKSHEET 1 1 Artifact Analysis Worksheet 1 Name Institute Artifact Analysis References Nimkulrat, N. (2013). Situating creative artifacts in art and design research. FormAkademisk-Research Journal of Design and Design Education, 6(2). © 2014 Laureate Education, Inc. Page 3 of 3 The Trouble with Gay Rights: Race and the Politics of Sexual Orientation in Philadelphia, 1969-1982 Kevin J. Mumford In 1985 the veteran civil rights activist Bayard Rustin joined a gay and lesbian coalition in New York City that was about to make a final push for passage of an amendment to the city's administrative code to prohibit discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation. Rustin wrote to the city council and to Mayor Edward I. Koch, vowed to

- 2. lobby the four opposing African American councilmen, and called for "the extension of freedom and justice for all Americans."' Unusual for Rustin, in this instance his activism ceremoniously concluded rather than pio- neered a social movement for change when the city council passed the bill the next year. More than fifteen years before, the first gay liberationists had introduced such a bill that was defeated by stiff opposition from conservative politicians and religious leaders. That mobilization helped spark organizing and demonstrating for similar laws in cities and towns during the 1970s and 1980s—a local political movement and discourse that remains largely unexamined. In recent writing on sexual politics, however, Matthew D. Lassiter, Robert O . Self, Whitney Strub, and others have analyzed controversies over gay visibility in the media, conflicts over the regulation of urban vice, and the political cooptation of pornography to understand shifts in American liberalism, and they suggest that the rise of gay liberation served as a foil against which liberals reconfigured the public/private divide and conservatives mobilized a rightward political turn. From another perspective, despite the rise of the New Right, the cause of gays and lesbians did advance during the 1970s, with the proliferation of community pride, new national organi- zations, and the passage of protective ordinances. Utilizing a case study of Philadelphia, this essay examines how the pursuit of equal protection led gays and lesbians to clash with reli-

- 3. gious and racial conservatives who challenged not only their rights but also their legitimacy Kevin J. Mumford is a member of the Department of History at the University of Iowa He wishes to thank the following for encouragement and advice: Clarissa Atkins, Nan Alamilla Boyd, Zoe Burk- bolder, Christopher Capozzola, Matthew Countryman, Rachel Devlin, Steve Estes, Estelle Freedman, Thomas Guglielmo, Evelyn Brooks Higginbotham, Andrew Kahrl, Linda Kerber, Scott Kurashige, Kenneth Mack, Charles Morris, David Roediger, Bob Skiba, Marc Stein, Shelton Stromquist. the audiences of the Charles Warren Center for Studies in American History and the 2009 annual meeting of the Organization of American Historians, and the anonymous reviewers for theJAH. ' Bayard Rustin, memo, March 11, 1986, in 7^?ß/Z)iari^/?«jft«Pi7/)frj. ed. Bayard Rustin and Nanette Dobrosky (Frederick, 1988); Rustin to Edward 1. Koch, Feb. 2, 1985, ibid; "Bayard Rustin's Statement on Proposed Amend.- ments to Law Banning Discrimination on the Basis of Sexual Orientation," April 17, 1986, ibid,; Rustin to Howard N. Meyer, Dec. 8, 1986, ibid; Rustin to Hon. Mary Pinkett, March 22, 1985, ibid.; John D'Emilio, Lost Prophet: The Life and Times of Bayard Rustin (New York, 2003), 489- 90; "Text of the New Bill of Rights," New York Times, Jan. 23, 1986, p. B2; "Rights Measure Ready for Vote after 12 Years," ibid., March 20, 1986, p. Bl; "Amending the Homosexual Rights Law," ibid.. May 3, 1986, p. A26. doi: 10.1O93/jahist/jarl39 © Ihe Author 2011. Published by Oxford University Press on behalf of the Organization of American Historians.

- 4. All rights reserved. For permissions, please e-mail: journals.permissions^poup.com June 2011 The Journal of American History 49 50 The Journal of American History June 2011 as a minority. It also explores how they developed racial diversity to respond to those threats and ultimately argues that gays and lesbians reconstructed their identities in the process of negotiating race relations and extending the liberal impulses of the 1960s into the 1980s.' Perhaps more than any other field, gay and lesbian studies concentrates on the origins and meanings of identity, creating discussions that often evolve into what is referred to as the essentialism versus constructionism debate. Essentialist scholars conceive of sexuality as a transhistorical essence located in the self, and they tend to see the gays, lesbians, or homosexuals of the past as identifying and desiring in much the same way as they do in the present. By contrast, social constructionist scholars argue that the very categories of homosexuality and heterosexuality change historically in relation to the forces of capital- ism, the family, urbanization, and scientific knowledge. Most historians are by nature constructionists, and they generally agree that by the outbreak of the Stonewall riots in 1969, when New York City police raided the gay-friendly Stonewall Inn and patrons

- 5. fought back, gay and lesbian identities and communities had formed across metropolitan America. Even so, sexual historians entertain a variety of interpretations about which processes or forces most affected the dynamics of identification. Anne Enke reconstructed 1970s civic spaces (such as dance halls and ballparks) and Martin Meeker pointed to contact zones of literature, periodicals, and photographs to describe areas of popular interaction that defined sexual subjectivities. Margot Canaday uncovered the extensive operation of constitu- tive regulation by what she termed the "straight state" to illustrate the powers of government interdiction and neglect, and Joanne Meyerowitz analyzed paradigms of racial and sexual knowledge to uncover changing processes of subjective interpolation that sometimes served as self-representations. In turn, my reconstruction of the politics of sexual orientation in Phila- delphia highlights the impact of intersections of race and sexuality on identity formation. As Matthew J. Countryman demonstrated in his study of civil rights and black power movements in Philadelphia, black leadership protested against workplace discrimination, promoted educational reform, and gained control in municipal government. At the same time, gay organizers, volunteers, witnesses, and audiences in the city, along with readers of the gay press and other media, were influenced by black political actors and gay people of color as they struggled for a place in the rights revolution of the 1970s.' By the rights revolution, I not only refer to Jacquelyn Dowd Hall's phrase the "long civil

- 6. rights movement" and her influential reading of racial struggle that extended the chronology of the movement, enlarged its scope from the South to the nation, and stressed the role of working-class politics, but I also incorporate what the sociologist John Skrentny conceived of as a minority rights revolution, or the expansion of the black civil rights movement ^ Bruce J. Schulman, The Seventies: The Great Shift in American Culture, Society, and Politics (New York, 2002); Matthew D. Lassiter, "Inventing Family Values," in Rightward Bound: Making America Conservative in the 1970s, ed. Bruce J. Schulman and Julian Zelizer (Cambridge, Mass., 2008), 13-28; Robert O. Self, "Sex in the City: The Politics of Sexual Liberalism in Los Angeles, 1963-1979," Gender and History, 20 (Aug. 2008), 288-311; Whitney Strub, Perversion for Profit: The Politics of Pornography and the Rise of the New Right (New York, 2010), 260-61 ; Josh Sides, "Excavating the Postwar Sex District in San Francisco," Journal of Urban History, 32 (March 2006), 355-79; Peter Braunstein, '"Adults Only': The Construction of the Erotic City in New York during the 1970s," in America in the Seventies, ed. Beth L. Bailey and David Färber (Lawrence, 2004), 129-56. esp. 146. ' Anne Enke, Finding the Movement: Sexuality, Contested Space, and Feminist Activism (Durham, N.C., 2007); Margot Canaday, The Straight State: Sexuality and Citizenship in Twentieth Century America (Princeton, 2009); Joanne Meyerowitz, '"How Common Culture Shapes the Separate Lives': Sexuality, Race, and Mid-Twentieth-Century Social Constructionist "Vnon^u Journal of American History, 96 (March 2010), 1057—84; Joanne Meyerowitz, "Transnational Sex and U.S. Wsx.ov¡^ American Historical Review, 14 (Dec. 2009), 1273-86; Matthew J. Countryman,

- 7. Up South: Civil Rights and Black Power in Philadelphia (Philadelphia, 2006), 117-52, 236-44, 312-27. Race and the Politics of Sexual Orientation in Philadelphia, 1969-1982 51 to include women, the disabled, the elderly, and other groups. His synthesis argued that "though victimized like blacks, gays and lesbians were not legitimate victims," in part because they failed to demonstrate how they were analogous to recognized groups. Historians of the legal regulation of sexuality have focused more on the issues of marriage and sodomy than on antidiscrimination legislation, while the recent growth of historiography on the northern civil rights movement largely overlooks gays and lesbians. Instead, the study of sexual orientation ordinances has been taken up by social scientists who measure discrete variables—religiosity, population size, socioeconomic status, and education—to explain why some locations passed laws and others did not. Following their lead, my analysis com- pares the legislative failure in 1975 to the eventual legislative success in 1982 in Philadelphia but focuses less on why it occurred than on how it occurred, in part because of how race became crucial to arguments against gay rights as well as central to their passage. Although historians have examined the impact of race on sexuality, particularly in studies of "misce- genation," relatively few studies of gay and lesbian communities have done so. My analysis

- 8. pursues the same sort of questions about homophobia that historians traditionally ask about racism: What were the dominant images and logics presented to the public? What did it justify? How did it respond to challenges and reform? My work also locates a kind of racial conflict between white gays and black gays that undermined the movement from within, which the historian of feminism Winifred Breines has conceptualized as a cycle of personal misunderstanding that troubled social movements—one of "profound racial dis- tance and tentative reconciliation." In Philadelphia and other cities with significant minor- ity demographics, sexual politics operated in some relationship to patterns of race relations."* Race and Gay Liberation Since the emergence of modern discourse on gay and lesbian identity, writers and aca- demics have often compared the condition of the homosexual to that of a racial minority. •• Jacquelyn Dowd Hall, "The Long Civil Rights Movement and the Political Uses of the Past," Journal of American History, 91 (March 2005), 1233-63; John D. Skrentny, The Minority Rights Revolution (Cambridge, Mass., 2002), 20, 304-5, 315, 326. On the long civil rights movement, see Sundidata Keita Cha-Jua and Clarence Lang, "The 'Long Movement' as Vampire: Temporal and Spatial Fallacies in Recent Black Freedom Smd^its," Journal of/^can American History, 92 (Spring 2007), 265-88; and Samuel Walker, The Rights Revolution: Rights and Com- munity in Modern America (New York, 1998), 44-48. On the long civil rights movement and working-class politics,

- 9. see Nancy MacLean, Ereedom Is Not Enough: The Opening of the American Workplace (Cambridge, Mass., 2006). For studies of sexual orientation ordinances, see Kenneth D. Wald, James W. Button, and Barbara A. Rienzo. "The Politics of Gay Rights in American Communities: Explaining Antidiscrimination Ordinances and Policies,"" Ameri- can Journal of Political Science, 40 (Nov. 1996), 1157-78; Gary Mucciaroni, Same Sex, Different Politics: Success and Eailure in the Struggles over Gay Rights (Chicago, 2008), 31; Craig A. Rimmerman, Kenneth D. Wald, and Clyde Wilcox, Ihe Politics of Gay Rights (Chicago, 2000) ; and Wayne Van der Meide, Legist/! ting Equality: A Review of Laws Affecting Gay, Lesbian, Bisexual, and Transgendered People in the United States (Washington, 2004). On Philadelphia gay institutions and sexual orientation rights, see Robert W. Bailey, Gay Politics, Urban Politics: Identity and Econom- ics in the Urban Setting (New York, 1999), 249-79. On the impact of race on sexuality, see Peggy Pa.scoe, What Comes Naturally: Miscegenation Law and the Making of Race in America (New York, 2009); Renee C. Romano. Race Mixing: Black-White Marriage in Postwar America (Cambridge, Mass., 2003); David !.. Chappell, A Stone of Hope: Prophetic Religion and the Death of Jim Crow (Chapel Hill, 2004), 114-18; White Interveners in Still v, Savannah- Chatham County Board of Education, "In Defense of School Segregation,"" in The Development of Segregationist Thought, ed. I. A. Newby (Homewood, 1968), 146-53; Pete Daniel, Lost Revolutions: The South in the 1950s (Chapel Hill, 2000), 148-75; and 1. A. Newby,//'w Crow's Defense: Anti-Negro Thought in America, 1900-1930 (Baton Rouge, 1965), 92-95. Winifred Breines, The Trouble between Us: An Uneasy History of the White and Black Women in the Eeminist Movement (New York, 2006), 7. On race and feminism, see also Sara M. Evans, Personal Politics: The Roots of Women's Liberation in the Civil Rights Movement and the New Left (New York, 1979); and Anne

- 10. M. Valk, Radical Sisters: Second-Wave Eeminism and Black Liberation in Washington, D.C. (Urbana, 2008). 52 The Journal of American History June 2011 In his influential 1951 treatise. The Homosexual Minority in America, Daniel Webster Cory included homosexuals in the so-called minority problem of Jews and Negroes, as did some of the writings of the gay black novelist James Baldwin and brief letters by the black playwright Lorraine Hansberry that were published in a 1957 issue of a lesbian journal. Even so, what was known as the homophile movement (a number of advocacy organizations founded in the postwar era) remained largely white and more culturally, strategically, and personally conservative. In his classic account of homophile politics, John D'Emilio argued that they were influenced by the "headline-making black civil rights movement," but that the rank and file sought a kind of invisible integration and could be compared to only the most conservative of black organizations. My own reading of the national organizational journals—Mattachine Review, the Ladder, and ONE— revealed that homophiles were more involved in efforts to achieve civil liberties and gain public acceptance than demonstrating for rights, and they infrequently mentioned African Americans. Conversely, in the 1950s the black popular periodical/i?i routinely ran stories on homosexuality or gay sex scandals, though rarely in

- 11. connection with civil rights. O n rare occasions writers observed the intersection of the two causes. In 1962 the homo- phile publication ONE published a review that characterized James Baldwin as "one of a number of current writers who is discovering a homosexual dimension to the current Negro revolution."' By the 1960s, homophiles in Philadelphia had begun to adapt what Marc Stein termed "multiple models of African American resistance" to the advancement of their cause, and on July 4, 1965, they held the first Annual Reminder demonstration at Independence Hall to demand recognition of their rights of citizenship. Even before the 1969 Stonewall riots, Philadelphia gays and lesbians had formed the Homophile Action League (HAL) to break away from the civility of the homophiles; a week after the riots, HAL and other radicalized activists challenged the conventionality of the fifth Annual Reminder by reftis- ing to conform to its usual dress code. The new radical HAL later discovered less rebellion and more apathy in its ranks, however, and therefore urged readers to follow "our fellow victims of discrimination and oppression—blacks, women, the poor, political dissi- dents—[who] are fervently pressing their battles." In 1970 the HAL announced that it had testified for a "state Human Rights Act" before the state platform committees of both the Democratic and Republican parties. The league also sponsored a booth where crowds of supporters "filled 10 pages of the homosexual 'civil rights'

- 12. petition." Similarly, Martin Duberman stressed the connections of race and sexuality in a narrative on the Stonewall ^ Daniel Webster Cory, The Homosexual in America: A Subjective Approach (NewYork, 1951), 4; Letter from L. N. H.[Lorraine Hansberry], Ladder, 1 (May 1957), 26-28. On Lorraine Hansberry's letters, see also Lisbeth Lipari, "The Rhetoric of Intersectionality: Lorraine Hansberry's 1957 Letters to the Ladder," in Queering Public Address: Sexualities in American Historical Discourse, ed. Charles E. Morris III (Columbia, S.C., 2007), 233-35; and Cheryl Higashida, "To Be(come) Young, Gay, and Black: Lorraine Hansberry's Existentialist Routes to Anticolonialism," American Quarterly, 60 (Dec. 2008), 899-924. James Baldwin, Another Country (New York, 1962); James Baldwin, "The Male Prison," in The Price of the Ticket: Collected Nonfiction, 1948-1985, by James Baldwin (New York, 1985), 101-05; John D'Emilio, Sexual Politics, Sexual Communities: The Making of a Homosexual Minority in the United States, 1940-1970 (Chicago, 1982), 174, 224; Chuck Stanley, review of Another Country by James Baldwin, One, 10 (Nov. 1962), 21-22. Andrew Bradbury, "Race and Sex," ibid, 12 (Oct. 1964), 17-21; Review of "The Toilet" by Le Roi Jones, ibid., 13 (March 1965), 16; Richard Mayer, review o( Giovanni's Room by James Baldwin, Matta- chine Review, 3 (April 1957), 33; 'A Moral Revolution: For Homosexuals?," Pursuit and Symposium, 1 (March—April 1966), 31—33. On homophile ethnic analogy, see Barbara Gittings, "Testimony for Human Relations Commission, Philadelphia City Hall Annex," June 5, 1974, Philadelphia City Council file, box 8, Papers of the Philadelphia Lesbian and Gay Task Force (Samuel Paley Library, Temple University, Philadelphia, Pa.).

- 13. Race and the Politics of Sexual Orientation in Philadelphia, 1969-1982 53 moment that featured black and Puerto Rican transgender rioters. If nothing else, the riot exposed the multicultural nature of gay community life and the movement's sharp escala- tion of tactical aggressiveness. Yet much of the historical scholarship on and some of the writings from the gay liberation era center their radical critiques of patriarchy and the necessity of "coming out," and they interpretively highlight the ideological influences of anti-imperialism, radical feminism, and the New Left, while losing sight of race.'' In complicated and sometimes forgotten ways, the civil rights and black power move- ments continued to influence gay liberation. Perhaps the most influential gay liberation essay of the era, "Refugees from Amerika: A Cay Manifesto," was penned by the white civil rights activist Carl Wittman. While an undergraduate at Swarthmore College, Wittman had joined the desegregation movement in Cambridge, Maryland, and later helped organize poor black neighborhoods in Newark, New Jersey. He had authored a major paper for the New Lefi: on interracial organizing that urged activists to join multi- cultural coalitions and to see economic inequality and racial oppression as interconnected. In the manifesto he argued that the black and gay movements faced a common enemy of "police, city hall, capitalism." He proposed that the two work

- 14. together, but also acknowl- edged barriers to the revolution "because of the uptightness and super-masculinity of many black men (which is understandable)."'' Attempts to define black masculinity within the black power movement became a troubling point of conflict for gay liberationists, however. In his controversial 1968 mem- oir. Soul on Ice, the black radical Eldridge Cleaver wrote scathingly of homosexuality— declaring it "a racial death-wish," a "sickness" worse than infanticide—and he infamously insulted James Baldwin for his gayness. Though a reviewer for the black leftist or nation- alist journal the Liberator acknowledged that "Cleaver is no [Oscar] Wilde, to be sure," although he did admire Cleaver's "societal convictions about drugs, sexual appetites." By contrast, a gay writer declared that "we are weary of Eldridge Cleaver's put-downs of James Baldwin on account of his homosexual leanings," and another criticized Cleaver for buying into the myth of American masculinity and believing that "if the black man would only be given back his balls," he could promise the "collapse of the effeminate, corrupt, impotent, and often homosexual white rules." Although Cleaver became an evangelical Christian and championed black female sexual liberation, he continued to object to homosexuality. In 1978 he appeared on a radio talk show with the Temple University history professor Dennis Rubini, who in 1975 had helped pass a resolution at

- 15. •* Marc Stein, City of Sisterly and Brotherly Loves: Lesbian and Gay Philadelphia, 1945-1972 (Chicago, 2000), 293; C. R,"GaY Politics," Homophile Action Newsletter, 2 (May-June 1970), 1. On race coalition, see "Homosexuals as a Minority," ibid, 2 (Nov.-Dec. 1969), 2 - 3 ; and "h.a.l. Notes," ibid, (March-April 1970), 5, On the Homo- phile Action League petition for a rights law, see Barbara Berthong, "Gay Politics," ibid,, 3 (Sept. 1970), 2; and Martin B. Duberman, Stonewall {New York, 1993), 112-14; Terrence Kissack, "Freaking Fag Revolutionaries: New York's Gay Liberation Front, 1969-Ï971." Radical History Review, 62 (Spring 1995), 105-34. On anti-imperialism, see Ian Lekus, "Queer Harvests: Homosexuality, the U.S. New Left, and the Venceremos Brigades to Cuba," ibid., 89 (Spring 2004), 57-91. Stein, City of Sisterly and Brotherly Loves, 231-32, 291-95. C. E, "Editorial," Homophile Action Newsletter, 2 (Nov.-Dec. 1969), 3; "In the Movement: Gay Liberation Front," ibid., 1 (Oct. 1969), 8. ' Carl Wittman, "Refugees from Amerika: A Gay Manifesto," Liberation, 14 (Feb. 1970), 18-33. On the importance of Carl Wittman's essay to gay liberation, see Rictor Norton, "Reflections on the Gay Movement," in Gay Roots: An Anthology of Gay History, Sex, Politics, and Culture, ed. Winston Leyland (San Francisco, 1991), 9 6 - 97. On Carl Wittman, seeTomHayden, Reunion: A Memoir (New York, 1988), 161-62; and Wesley Hogan, "How Democracy Travels: SNCC, Swarthmore Students, and the Growth of the Student Movement in the North, 1961- 1964," Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography, 126 (]xy 2002), 437-70. Thaddeus Russell, "The Color of Discipline: Civil Rights and Black Sexuality," American Quarterly, 60 (March 2008), 101-28.

- 16. 54 The Journal of American History June 2011 the Organization of American Historians anntial meeting that affirmed the rights of scholars to study sexual minorities. On the show. Cleaver again attacked gays, asserting "I personally think that homosexuality is a sickness as well as a sin" that reflects confusion about the sexes. He reportedly added, "I look upon Dennis Rubini as a twisted fellow." When Rubini countered that the nineteenth-century Philadelphia physician Benjamin Rush believed that blackness was a "benign form of leprosy," Cleaver responded only with, "I'm glad it was benign."" Despite the fallout from Cleaver's writing and rhetoric, gay radicals reached out to the black power movement. In the months following the Stonewall riots, gay men in New York City organized the first Gay Liberation Front (GLF) and by 1971 a branch had blossomed in Philadelphia. Prompted by the early gay rights activist Frank Kameny, many organizers adopted the phrase "gay is good," mirroring Stokely Carmichael's use of the slogan "black is beautiful." The new gay liberationists turned up the volume of their demands with calls for "gay power" and "gay power to gay people." At a high point of cross-identification the New York branch of the GLF proposed to pursue political alignment with the Black Panther party (BPP), and in 1970 the GLF voted to donate $500 to a BPP legal defense fiind but a number of members objected because of the BPP'S reputed homophobia. The GLF did continue to

- 17. advertise BPP events to its membership, and in turn the BPP chairman Huey Nevrton issued "A Letter to the Revolutionary Brothers and Sisters about the Women's Liberation and Gay Liberation Movements" in 1970. In the widely reprinted document, Newton denounced homophobia, instructed his comrades to "gain security in ourselves," and, in calling for an end to antigay epithets, even ventured the assertion that a "homosexual could be the most revolutionary." At one point in the text he asked, "what made them homosexual?" When he answered, "perhaps it's a phenomenon that I don't understand entirely," Newton implicitly disavowed rather than affirmed homosexuality.' The response to Newton and the BPP varied. Some argued to forgive their causal use of the term faggot, while others did not; some called for a coalition in spirit or with contri- butions, while others found that position to be faddish. Significant numbers of gays and lesbians did turn out to participate in the BPP'S 1970 Revolutionary People's Constitu- tional Convention in Philadelphia in hopes of creating an alternative society and govern- ment, and at least sixty attended a follow-up convention in Washington, D.C. A white gay activist recalled a sense of solidarity when he donned "brightly colored, hand- crocheted berets (like the kind the Panthers wore)" at the Philadelphia convention. At the Washington, D . C , convention, approximately a dozen gay activists demonstrated against ' Eldridge Cleaver, Soul on Ice (New York, 1968), 109-10;

- 18. Donn Teal, The Gay Militants: How Gay Liberation Began in America, 1969—1971 (New York, 1971), 94. Francis Lucas, review of Soul on Ice by Eldridge Cleaver, Liberator, (Oct. 1968), 19; John P LeRoy, "Eldridge Cleaver's Missing Balls," GAY, May 11, 1970, p. 7. On Dennis Rubini at the Organization of American Historians annual meeting, see "Historians Aflirm Gay Studies," Philadelphia Weekly Gayzette, May 9-16, 1975, p. 2. "Cleaver Slices Gays," Philadelphia Gay News, Oct. 1978. Magdalena J. Zabotowska, James Baldwin's Turkish Decade: Erotics of Exile (Durham, N.C., 2009), 231-32; and Tracye Mathews, "'No One Ever Asks, What a Man's Place in the Revolution Is': Gender and the Politics of the Black Panther Party, 1966-1971," in The Black Panther Party [Reconsidered], ed. Charles E. Jones (Baltimore, 1998), 2 8 1 . '' On "gay is good," see Teal, Gay Militants, 188. On Frank Kameny, see Toby Marorta, The Politics of Homosex- uality (Boston, 1981), 62-67. On "gay power to gay people," see Teal, Gay Militants, 175. "The Gay Militants: A Book of Genesis," GAY, May 24, 1971, pp. 14—15. On the Gay Liberation Front and the Black Panther party, see Teal, Gay Militants, 166—67; and Huey Newton, "A Letter to the Revolutionary Brothers and Sisters about Women's Liberation and Gay Liberation Movements," in Black Men on Race, Gender, and Sexuality: A Critical Reader, ed. Devon Carbado (New York, 1999), 387-89. Race and the Politics of Sexual Orientation in Philadelphia, 1969-1982 55 a restaurant for allegedly discriminating on the hasis of race. There are scattered shards of

- 19. evidence that black gay men, including some who were incarcerated, participated in some way in the BPP, but there is little indication that Newton's statement on gay liberation translated into widespread inclusion of gays and lesbians in the organization.'" From the perspective ofthe GLF, the interchange with the BPP exacerbated the tensions and divisions among gay activists to a greater extent than it ignited a broad revolutionary coalition. Shortly after the GLF voted to approve the donation to the BPP, opponents of the move broke away to start the Gay Activists Alliance (GAA) to operate as an exclusively homosexual organization with a clearly defined structure. The first president of the GAA, Jim Owles, downplayed the racial overtones of the hreak, hut he also declared that he believed that the "Black Panthers were strongly anti-gay," and in an interview he referred to the gay activists as a minority within the homosexual minority—"the most peculiar of freaks." The new GAA did not prioritize diversity in the same way that the GLF did, and while the Philadelphia branch of the GLF reportedly had once attracted significant num- hers of people of color, hy the early 1970s it had declined. Some radicals joined and thrived in the GAA, at least in the heginning stages when the organization served as a front for diverse activities, such as newsletters, media visibility campaigns, and study groups, and provided enough flexibility for and openness to diversity of race, class, and gender. Even so, the GAA was seen as more academic, more

- 20. intellectual, less street oriented, and more white—than the liberation fronts. Yet the organization retained a revolutionary spirit of liberation and the syntax of hlack power, proclaiming "gay is angry!" and "gay is proud!" in fliers and memos. The activists in the GAA organized under a vision of civil rights, hut they were blind to the whiteness of their ranks." In New York and Philadelphia the GAA staged demonstrations to educate the public about and lobby for local and federal governmental rights, and in 1970 the New York City GAA specifically pressed for a city council bill (known as Intro 475) to prohibit dis- crimination in housing, employment, and accommodations. The demonstrators were known for utilizing disruptive tactics called zaps to get attention and win support. More than forty GAA members disrupted the taping of a television talk show with the New York City mayor John Lindsay and forced the mayor's staff to agree to meet with them. "1̂ "Gay Liberation Blooms in Philadelphia," GAY, ]uy 13, 1970, p. 12; "Gay Bar Charged with Black/Female Bias," ihid., March 1, 1971, p. 12; "Black Panther Party Supports Gay Liberation," ibid., Sept. 14, 1970, pp. 3, 12; John P LeRoy, "Ball a Panther," ibid, May 18, 1970, p. 15; Hal Tarr, "A Consciousness Raised," in Smash the Church, Smash the State.' The Early Years of Gay Liberation, ed. Tommi Avicolli Mecca (San Francisco, 2009), 25-26, 29. On women's participation in the Revolutionary People's Constitutional Conventions, see Valk, Radical Sisters, 128-29; and Stein, City of Sisterly and Brotherly Loves, 334-36. On dual black participation, see Diwas Kc, "Of Conscious-

- 21. ness and Criticism: Identity in the Intersection of the Gay Liberation Front and the Young Lords Party" (M.A. thesis, Sarah Lawrence College, 2005), 17-18. ' ' David Eisenbach, Gay Power: An American Revolution (New York, 2006), 140; Kissack, "Freaking Fag Revo- lutionaries," 113, 116-17; Teal, Gay Militants, 106; "Jim Owles," in The Gay Crusaders, ed. Kay Tobin and Randy Wicker (New York, 1972), 35; "Where the Action Is: An Interview with Jim Owles," GAY, Sept. 7, 1970, pp. 14- 15; "GAA-NY Wins Court Battle for Incorporation," ibid., April 3, 1972, p. 6; Jeffrey Escoflier interview by Kevin Mumford, July 2009, notes (in Kevin Mumford's possession). On the activities ofthe Gay Activists Alliance (GAA), see "Gay Activists Alliance," memo, Feb. 22, 1972, folder 3, box 2, Harry Langhorne Papers (Rare and Manuscript Collections, Cornell University Library, Ithaca, N.Y.). "Constitution of GAA," folder 3, box 2, Langhorne Papers. On diversity in the GAA, see James Roberts, "Pre-Now," in Smash the Church, Smash the State!, ed. Mecca, 46. "Protest This Anti-Gay Bigotry," memo, April 1972, GAA folder. Ephemera Collection (John J. Wilcox Jr. Library and Archives, William Way Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Community Center, Philadelphia); and "Current GAA Activities Include," ibid.; "Minutes—Gay Media Project," Dec. 18, 1975, folder 19, box 2, Langhorne Papers. 56 The Journal of American History June 2011 The GAA also used a zap to convince the city council representative from Creenwich Village to introduce the new bill and then approached the commisson on human rights,

- 22. winning early support from the civil rights activist and the chairperson Eleanor Holmes Norton. Although the GAA retained a registered, unpaid lobbyist, its effort to pass an antidiscrimination bill at the state level quietly failed after a lopsided vote. The GAA shifted its focus back to the city amendment and mounted more pressure on the city council. At the same time, the members of the Philadelphia HAL wrote that they supported the GAA more than the GLF, in part because the GAA distrusted the strategy of alignment with other groups and because it emphasized the benefits of equal rights. Alongside the GAA, the HAL called for fair employment and fair housing, and in 1970 the organization approached a liberal city council member about a bill in what it termed a "low-risk but high potential use of the political process."'^ By the 1970s, what was popularly termed the gay rights movement had many goals, including raising the movement's visibility in the media, decriminalizing sodomy, declas- sifying homosexuality as a mental disorder and ending harassment by police. Many of these objectives were shared with homophiles, but the post- Stonewall era organizations, particularly the new GAA, evolved within a larger culture of activism that race had deci- sively defined. It is hard to imagine the rebellion of gay liberationists in New York or Philadelphia without seeing their admiration for and clash with the black power move- ment, and it is harder still to understand the longer history of gay and lesbian rights

- 23. without reference to African Americans. Gay Rights as Civil Rights When the GAA began to organize for a sexual orientation law in Philadelphia it encoun- tered the complex of antidiscrimination codes that originated with the Fair Employment Practices Committee in 1941, the Philadelphia Human Relations Commission in 1951, and the Fair Practices Ordinance in 1962. In 1972 the GAA activists Harry Langhorne and Marc Segal first approached the city council to include protection for sexual orientation in a bill that proposed to add the category of sex to the Fair Practices Ordinance, but they were not successful. The following year, according to an account by Langhorne, they "began making the rounds" at city hall to gather support for Philadelphia City Council Bill 1275 for sexual orientation, but the powerful council members Isadore Bellis and George Schwartz reportedly considered the bill unpassable. Even so, Langhorne and Segal secured sponsorship promises from several other city council members, one of whom was '̂ "Historic Hearings Held in N.Y.C.," OîKNov. 22, 1971, p. 1; "City Council Leader Threatens Lindsay on Cay Bill," ibid, Feb. 7, 1972, p. 6; "City Councilmen Push Cay Protection Bill," ibid.. Feb. 15, 1971, p. 17; Stephan L. Cohen, The Gay Liberation Youth Movement in New York: "An Army of Lovers Cannot Fail" (New York, 2008), 147-50; Arthur Evans, "How to Zap Straights," The Gay Liberation Book, ed. Len Richmond and Cary Noguera (San Francisco, 1973), 111-15; "Police Harassment," Activist Alliance, n.d.,

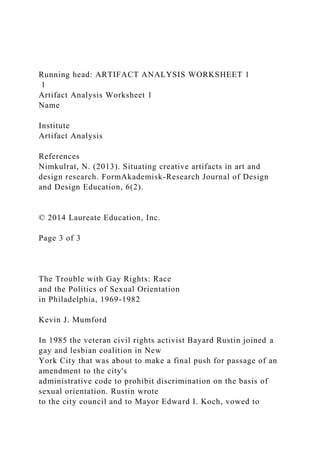

- 24. GAA folder. Ephemera Collection; "Protect Yourself from a Police Crack-Down," memo, n.d., ibid.; "We Interrupt This Program of Psychiatric Propaganda to Bring You the Following Message from Cay Pride," flyer, Dec. 9, 1971, ibid.; "Cay Activists Sponsor Petition," GAY, Feb. 16, 1970, p. 3; "GAA Confronts Lindsay at Channel 5," ibid.. May 11, 1970, p. 3; "N.Y. Rights Commissioner Backs Employ- ment Demands," ibid. May 18, 1970, p. 20; "Councilman Creitzer Yields to Cay Activists," ibid, June 1, 1970, p. 3; "GAA Tackles Five More Candidates," ibid, July 6, 1970, p. 1; "Penna. Politicals Hear Gay Spokesman," ibid., Sept. 7, 1970, p. 12; "New York Assembly Votes Down Rights Bill," ibid., Sept. 12, 1970, p. 1; CF., "Fighting the Fun and Games in Fun City," Homophile Action League Newsletter, 3 (Dec. 1970), 6-7; CF., "Between the Devil and the Deep Blue Sea," ibid.; C. F., "Editorial: Cay Politics," ibid, 2 (May- June 1970), 1; Testimony of Byrna Aronson, n.d.. Homophile Action League folder. Ephemera Collection. Race and the Politics of Sexual Orientation in Philadelphia, 1969-1982 57 Marc Segal (left) and Harry Langhorne (right) founded the Gay Activists Alliance in Philadelphia and organized the first campaign for a local sexual orientation ordinance, which was defeated in city council subcommittee hearings. Courtesy Marc Segal and the ?WIA- delphia Gay News. African American, and in 1974 the Law and Government Committee prepared to hold hearings on the bill to amend the Fair Practices Ordinance. The

- 25. subcommittee included two African Americans but also reflected the whiteness of Philadelphia—with identifiably Italian, Jewish, and Eastern European names—and several white senior members proved extraordinarily hostile to the gay and lesbian witnesses. In the early 1970s, the city's three largest white ethnic groups were Italian Americans (with a population of 132,630), Irish Americans (with a population of 122, 522), and German Americans (with a population of 68,468); presumably, many were Catholic—a factor that affected perceptions and val- ues related to homosexuality. At some moments in the hearings, attitudes undoubtedly reflected religious beliefs, at other moments they reflected competitive hostility to the arrival of a faction coming up through the political machine, and at others, personal animus toward homosexuals. If the council members were pressured into opposition by their religiously conservative constituency, none of them said so on the record. Rather, race became the central political reference." " Thomas J. Sugrue, "Affirmative Action from Below: Civil Rights, the Building Trades, and the Politics of Racial Equality in the Urban North, 945-969," Journal of American History, 91 (June 2004), 141-63. On City Council Bill 1275, see Stein, City of Sisterly and Brotherly Loves, 362. Harold I. Lief to Isadore Bellis, June 26, 1972, 1970s folder, Philadelphia History files. Ephemera Collection; "Gay Rights Are 1972 Election Year Issue," folder 3, box 2, Langhorne Papers; "Ad Hoc Committee of Gay Organizations, Including Gay Academic Union, Gay Activ- ists Alliance, Gay Democratic Club, Gay Legal Caucus, Dignity,

- 26. Lesbian Feminist Liberation, Mattachine Society, National Gay Task Force," press release, April 12, 1974, Philadelphia City Council 1275 folder, box 8, Papers of the Philadelphia Lesbian and Gay Task Force; "Bill No. 1275, Introduced April 18, 1974," Records of the Office of the City Clerk (City Hall, Philadelphia); Harry Unghorne, "Gay Rights Bill Dies—Another in Preparation," Philadel- phia Gay News, Jan. 3, 1976, p. A3; Marc Segal interview by Mumford, transcript, July 28, 2008 (in Mumford's possession); ¡980 Census of Population and Housing. Census Tracts. Philadelphia, Pa-N.J. Standard Metropolitan Statistical Area (2 vols., Washington, 1983), 1, 221, table P-8; "Lobbying Office Is Essential," Advocate, April 19, 1975, p. 11; "Lobby Effort Incorporated," ibid.. May 5, 1976, p. 6. 58 The Journal of American History June 2011 O n December 19, 1974, for the first day of hearings on Bill 1275, the chambers were full and several dozen witnesses were scheduled to testify before the seven-man panel. From the beginning of the councilmen's questioning, it was apparent that gays and lesbi- ans had to establish much more than their case of discrimination; they had to prove their minority status to opponents who deemed them immoral and unlike other groups that were traditionally protected under the umbrella of antidiscrimination discourse. Some witnesses therefore turned to tactics of enumeration. Harry Langhorne estimated the number of gays and lesbians in the city at 150,000, or approximately 10 percent of Phil-

- 27. adelphia exclusive of the suburbs, and Marc Segal estimated the homosexual population at 200,000. When the Reverend James A. Kennedy estimated the number at "upwards of 250,000," several members of the council became irate, and the councilman Joseph Coleman objected to what he felt was an implied comparison with blacks. He was "troubled, even on the civil rights aspect," because "a homosexual is a homosexual by choice," but "one does not determine one's race or what have you." In response to Cole- man's objections, Kennedy argued, in a simplistic and essentialist manner, that sexual orientation was determined "before a person is two or three years old" and "that is not a matter of choice."''* Supporters of the measure also had to overcome the association of gays and lesbians with criminality and sodomy. The state of Pennsylvania had long outlawed sodomy, charging "whoever carnally knows" animal or bird or any male or female by the anus or by the mouth with a felony and in 1973 reduced voluntary deviate sexual intercourse to a misdemeanor by adopting the model codes of the American Law Institute. The political theorist Wendy Brown argues that heterosexuals disavow homosexual behavior to assert the superiority of their group, and the legal historian William Eskridge points out that decriminalization of sodomy "was only possible in the states where the issue had not been homosexualized." In anticipation of accusations of sexual criminality, the lesbian feminist

- 28. activist and attorney Byrna Aronson testified at the city council hearings that some homo- sexuals remained celibate and deserved legal protection; she was not entirely convincing, however, since others admitted to being practicing homosexuals and nonetheless asked for protection from discrimination. Further, the city council president George Schwartz grilled a witness from the state attorney general's office on why the city council should pass a law that condoned criminal sexual behavior, and here the attorney argued it was impossible to know in advance if a couple applying for a lease to an apartment would practice deviate and illegal sexual acts." The Philadelphia debate appeared to be headed toward a showdown over morality. Reli- gious opponents had turned out in large numbers in part because of advertisements for the ''' "Testimony of Harry Langhorne before the Philadelphia City Council Committee on Law and Govern- ment," Dec. 18,1974, pcc Hearings on 1275, Records of the Office of the City Clerk; "Testimony of Mark Segal before the Philadelphia City Council Committee on Law and Government," ibid., 96; "Testimony of Harry Lang- horne before the Philadelphia City Council Committee on Law and Government," ibid., p. 14; "Testimony of the City Council Chairman," ibid,, 100-101 ; "Testimony of James A. Kennedy and Joseph Coleman before the Philadel- phia City Council Committee on Law and Government," Jan. 24, 1975, ibid., 257-58. '" On sodomy in Pennsylvania, see 18 Pa. Cons. Stat. Ann. 4501 (West 1963); 18 Pa. Cons. Stat. Ann. 3124 (West

- 29. 1983); and 18 Pa. Cons. Stat. Ann. 3123 (West 2000). Wendy Brown, "SuflFering the Paradoxes of Rights," in Left LegalismJLefi Critique, ed. Wendy Brown and Janet Halley (Durham, N.C., 2002), 429; William Eskridge, Dishonorable Passions: Sodomy Laws in America, 1861-2003 (New York, 2008), 197; "Testimony of Byrna Aronson before the Philadel- phia City Council Committee on Law and Government," KC Hearing on 1275, pp. 42—44; "Testimony of Barry Kohn before the Philadelphia City Council Committee on Law and Government," Jan. 24, 1975, ibid, 300-301. Race and the Politics of Sexual Orientation in Philadelphia, 1969-1982 59 event in congregations and seminaries. One clergyman presented the council with a peti- tion containing five-thousand signatures in opposition to the bill. The opponents argued that legally protecting gays and lesbians with antidiscrimination codes was tantamount to the endorsement of a behavior that they believed to be sinfial; that the bill compromised their conscience; and that the Bible governed sexual behavior and immorality. Neverthe- less, a systematic reading of the hearing testimony from start to finish suggests that, on the whole, a purely religious rationale never persuaded the city council. Indeed, many of the witnesses who represented a particular branch of faith or an individual church—from the Episcopalians to the Society of Friends to gay Catholics— testified in support of the mea- sure. Reflecting leftward shifts in American theology since the 1960s, gays and lesbians had

- 30. formed churches and religious groups, and by the 1970s increasing numbers of liberal churches and denominations began to welcome sexual minorities. Moreover, the Philadel- phia city council understood itself as a governmental institution and never asked questions of a theological nature. On several occasions the council members became somewhat impatient, asked for brevity, and refrained from extended questioning when opponents of the bill stood to read long passages from the Bible. At one point, the chairman chastised a witness: "I hate to say this, but you have been repetitious." When a black female recited scripture. Councilman Coleman attempted to lead her toward a more secular stance by asking, "then you don't think this is a civil rights issue there; is that how I understand you?" Her answer nonetheless resisted the steering: "I just feel like it's wrong, it's against god.""^ Even the most powerful religious witnesses, such as Fr. Charles McGroarty who repre- sented the archdiocese of Pennsylvania, stressed not only Catholic teachings on the repro- ductive purpose of sexuality and the role of family in Western civilization but also a more stringent definition of a minority that excluded homosexuals. When he began a discourse on the subject of family values, the chairman's questions led him to speak of race and "discrimination that took place because people were different, whether in looks, back- ground, et cetera." Then McGroarty pointed out that "to be an Irishman or an Italian is not necessarily a threat to society itself," as presumably

- 31. homosexuality was. When Marc Segal stepped up to testify, the rather hostile city council member Isadore Bellis, himself of Italian background, reiterated McGroarty's objection: "I'm being discriminated against because I'm black, because I'm Jewish, because I'm Italian, what have you, it would seem to me that the first thing [is to discover] whether or not in fact that person—well, it's easy to tell a black, but it's not easy to tell a Jew or an Italian or an Irishman." Neither gay and lesbian enumeration nor claims to real visibility seerned to answer the arguments that sexual orientation was not like race as a categorj' of discrimination.''' "̂ Monty D. Ledford to Kevin Mumford, e-mail, Dec. 1, 2007 (in Mumford's possession). On the leftward shift in theology, see Mark Oppenheimer, "The Inherent Worth and Dignity: Gay Unitarians and the Birth of Sexual Iblerance in Liberal KeVipon" Journal of the History of Sexuality, 1 Quly 1996), 73-80; Melissa M. Wilcox, "Of Markets and Missions: The Early History of the Universal Fellowship of the Metropolitan Community Churches," Religion and American Culture, 11 (Winter 2001), 83-108; Mary Jo Weaver, "Resisting Traditional Catholic Sexual Teaching: Pro-Choice Advocacy and Homosexual Support Groups," in What's Left: Liberal American Catholics, ed. Mary Jo Weaver (Bloomington, 1999), 88-108; Andrew Sullivan, "Alone Again, Naturally: The Catholic Church and the Homosexual," in Querying Religion: A Critical Anthology, ed. Gary David Comstock and Susan E. Henking (New York, 1997), 238-50; and Elliott Wright, "The Church and Gay Liberation," Christian Century, 89 (March 1971), 283. "Testimony of the City Council Chairman," 347; Testimony of Miss Lillian Fields before the Philadel-

- 32. phia City Council Committee on Law and Government," Kc Hearings on 1275, p. 273. " "Testimony of Father Charles McGroarty," KC Hearinp on 1275, pp. 82-84, 88-89; "Testimony of Joel Warren," ibid., 352; "Testimony of Joan DeForrest," ibid, 125-27; "Statement of Chairman [Isadore] Bellis," ibid., 99^100. 60 The Journal of American History June 2011 The Law and Government Committee of the Philadelphia City Council meets on Bill 1275, photographed for the Philadelphia Evening Bulletin in December 1974. Courtesy Urban Archive, Temple University Library. Even as hoth experts and victims stood to tell stories of the termination of employ- ment, denial of rental housing, and loss of child custody due to their sexual orientation, the testimony of opponents raised more questions ahout the significance of their minority status and the discrimination they faced. By the end of the first day of the hearings, the door that had heen pried open hy a string of witnesses speaking of prejudice was forcihly closed hy the testimony of a number of hlack religious witnesses who authoritatively rejected the comparison of racism and homophobia. First among them was the Reverend Melvin Floyd, the founder of Neighborhood Crusades, Inc. Floyd had served as a Phila- delphia police officer for almost fourteen years, and after entering the Baptist ministry in

- 33. 1966 and resigning from the force in 1972, he dedicated himself to social uplift through his church in Germantown. His organization attacked the gang problem hy attempting to reform hlack manhood, downplaying materialism and consumerism, protesting against hlaxploitation films, and railing against the sexual revolution. These were the sources of the antigay viewpoint that he brought to the city council hearings and that caused him to conclude: "The one thing ahout everything else that can destroy that kind of manhood is to come up with a generation or generations of homosexual black males." Insinuating that homosexuality was an essentially white phenomenon, Floyd heckoned the council to acknowledge the race of his allies: "As you look to the side here, 95 percent ofthe persons there are black," yet "100 percent [ofthe people] of any organizations of gay rights are white." If gay activists implied that they were heirs to the civil rights movement, Floyd called them out and asked, "Why did they tack it onto the civil rights hill? Because they wanted to make it difficult for you to say no, we won't pass it.""* '* Testimony of Reverend [Melvin] Floyd," I'cx: Hearings on 1275, pp. 213-14; Joseph E. Broadus, "Family Values vs. Homosexual Rights: Tradition Collides with an Elite Social Tide," in Black and Right: The Bold New Voice of Black Conservatives in America, ed. Stan Faryna, Brade Stetson, and Joseph G. Conti (Westport, 1997), 111—19; "A Gang Symposium," Philadelphia Tribune, Feb. 12, 1974; "Juvenile Aide Policeman Now a Baptist Minister," Philadelphia Evening Bulletin, Oct. 10, 1966, p. 1; "Honored

- 34. Policeman to Become Full Time 'Missionary of Streets,'" Philadelphia Inquirer, July 16, 1972, p. 18; "Blacks to Receive Philadelphia Award," Philadelphia Tribune, Feb. 24, 1976; Paul E. Long, "Gang Killings Down: Three Reasons," Feb. 8, 1977, typescript, (in Mumford's pos- session); "Testimony of Reverend Floyd," KC Hearings on 1275, pp. 210-14, esp. 214. Race and the Politics of Sexual Orientation in Philadelphia, 1969-1982 61 The Reverend Samuel Hart, another major black religious leader who broadcast weekly sermons on 120 radio stations, similarly stepped up to list the reasons why he opposed Bill 1275: homosexuality went against the "structural foundations of our society called the home" and betrayed what he termed the American way of life. Like Floyd, Hart also drew on racial authenticity to argue that "we hear much about the violation of the civil rights. It goes without saying I'm black, and therefore I know what discrimination is, and I'm not against civil rights." Although one local branch of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) and a black labor organization sent letters in support, no members from either organization turned out to testify. Almost by default, the religious conservatives became the recognized black voice of the race by articulating a unified view of the issues and categorically disavowing other views and groups.'''

- 35. Neither Floyd nor Hart appeared out of thin air, but rather they reflected the historic influence of the African American clergy in Philadelphia society and politics. Routinely identified as the leadership throughout the civil rights era, black clergymen appeared in and wrote for black newspapers and were summoned as community representatives in meetings with city officials, including the mayor. The expanding leadership included the Reverend William Banks, who did not testify at the hearings but who had gained atten- tion from the Philadelphia Tribune in 1973 for significantly increasing the size of his North Philadelphia congregation. He also wrote a weekly column for the paper in which he railed against the sexual revolution of pornography, birth control, and legalized abor- tion. He warned of "increased homosexuality and growing divorce rate," and in another column he provocatively asked: "What is gay?'" and "Is 'gay' Good?" He offered the answer, "No," gay was not good, and called for society to "abandon attempts to legalize degradation." He argued that legal protection could never change God's prohibition of homosexuality.'" Such commentary reflected the dimensions of black opinion about sexuality beyond the institution of the black church. A 1977 Gallup opinion poll on the hiring of homosexuals showed slightly more tolerance for homosexuals among nonwhite than white respondents, including more acceptance of their employment in public schools, but also reported that

- 36. whites were more likely to agree that homosexuals were capable of being good Christians or Jews (54 percent of whites compared to 48 percent of nonwhite respondents agreed). The survey reflected a significant distinction between objecting to discrimination, which African Americans may have found more troubling, and affirming sexual identity in other arenas of recognition. Both white and nonwhite respondents were within several percent- age points of each other on many questions, and yet historically speaking it may be the case that African American opinion reflected distinct perceptual contexts and experiences. Beginning with the black migration to the urban North during the early twentieth century. ''' "Testimony of Samuel Hart," « r e / / œ r / » ^ on 1275, p. 147; James Jones to Harry Langhorne, May 8, 1974, Philadelphia City Council folder, box 8, Papers of the Philadelphia Lesbian and Gay Task Force; Alphonso Deal to Councilman William Boyle, June 10, 1974, ibid.; "Endorsements for Gay Civil Rights," n.d., memo, ibid. C-heryl J. Sanders, "Sexual Orientation and Human Rights Discourse in the African American Churches," in Sexual Orientation and Human Rights in American Religious Discourse, ed. Saul M. Oylan and Martha C. Nussbaum (New York, 1998), 178-84; Horace L. Griffin, Their Own Receive Them Not: Aftican American Lesbians and Gays in Black Churches [Clevthná, 2006), 142-65; "Testimony of Doris Neal," pcc Hearings on 1275, pp. 167-68; "Testi- mony of Lillian Fields," ibid., 271 ; "Rev. Banks Puts New Life in Union Baptist Church," Philadelphia Tribune, Feb. 10, 1973; Rev. Wm. L Banks, "Will Marriage Ever Become Obsolete?," ibid, Feb. 13, 1973; Rev. W. L. Banks,

- 37. "Flee Fornication," ibid., April 14, 1973; "Rev. W. L. Banks Writes, Is Gay Good," ibid.. May 29, 1973; "Rev. W. L. Banks Writes, Wrong Rights," ibid., July 13, 1976; "Rizzo Meets with Black Ministers," ibid., Sept. 29. 1978. 62 The Journal of American History June 2011 hlack social scientists such as W. E. B. Du Bois and E. Franklin Frazier had penned a kind of defense ofthe morality of black urhanites in response to charges that they exhibited vice and disregarded matrimony before pregnancy, revealing a particular concern with what historians have termed the politics of respectability. In 1965 the leaking of the Moynihan Report caused a steep increase both in the discourse about black immorality and the schol- arly defense against it. Assistant Secretary of Labor Daniel Patrick Moynihan aroused great controversy with his conclusion that single female-headed black families perpetually reproduced poverty and underachievement. He borrowed the unfortunate phrase "tangle of pathology" from his friend, the social scientist Kenneth Clark, to describe a black matri- archal culture that overwhelmed the black male, and he proposed masculine labor and an "utterly masculine world" to combat the pathology. But popular commentators easily con- nected the purported deviance of the black family to the incidence of homosexuality, dis- persing homophobia into public debates on race. Writing in a 1966 issue of Ebony magazine, a psychiatrist warned ofthe problems faced by "both

- 38. girls and boys brought up in the matriarchal family climate," specifically how "the son will abandon any attempt to free himself from the tyrannical rule ofthe mother . . . and resolve his need to be loved by becoming a homosexual." By the 1970s the black sociologist Robert Staples and the black psychiatrist Alvin F. Poussaint both staunchly defended the black family structure from the lingering cloud of the Moynihan Report by distancing it from the problem of homosexu- ality. Staples linked homosexuality to diminished masculinity and impotence, and Pous- saint reported a "significant incidence of homosexuality, impotence, and premature ejaculation," but neither blamed the matriarchal family. As a medical researcher with an extensive library and collection of clippings, Poussaint noted the paucity of writings on black homosexuality. If he knew of the ongoing efforts to remove homosexuality from the classification of psychiatric illnesses, he appeared unsympathetic. In the process of defend- ing the morality of African Americans, a number of experts had, with the disavowal of homosexuality, answered the innuendo that the matriarchal family effeminized the son.^' In Philadelphia, the homosexual image in the black mind also reflected contemporane- ous social troubles—sex scandals, crime and prison, and juvenile delinquency. In a major Philadelphia scandal, the staff at a local juvenile detention facility, the Youth Study Cen- ter, faced charges of involuntary deviate sexual intercourse and corrupting the morals of a

- 39. minor. As the story broke, two black candidates running for the office of mayor pushed to close the facility and characterized the alleged homosexual conduct as "disgusting." '̂ Alex M. Gallup, ed.. The Gallup Poll Cumulative Index, Public Opinion, 1972-1977 (2 vols., Wilmington, 1978), II, 1137-45, esp. 1145; "The Epidemic ofTeenage Pregnancy," New York Times, June 18, 1978, p. E6; "Sex and the Modern Teenager," Philadelphia Evening Bulletin, Sept. 21, 1978, p. 24; "Sex among Teens: More Girls Have It. but Not as Often," Philadelphia Inquirer, April 8, 1977, p. 5A; "wocN Tentative Statement of Purpose," n.d., box 5, Women Organized against Rape Papers (Paley Library); W. E. B. Du Bois, ed.. The Negro American Family (Atlanta, 1908); E. Franklin Frazier, The Negro Family in Chicago (Chicago, 1932); Allison Davis and John Dollard, Children of Bondage: The Personality Devebprnent of Negro Youth in the Urban South (Washington, 1940); Lee Rainwater and William L. Yancey, The Moynihan Report and the Politics of Controversy (Cambridge, Mass., 1967), 88; Kermit Mehlinger, "The Sexual Revolution," Ebony, 21 (Aug. 1966), 57-58; "Pettigrew," memo, Dec. 28, 1964, file 8, box 166, Daniel Patrick Moynihan Papers (Manuscript Division, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C.); Notes by Daniel Patrick Moynihan, n.d., file 9, ibid. Robert Staples, "The Myth of Black Matriarchy," Black Scholar, 1 (Jan.-Feb. 1970), 8-9, 11-12; Robert Staples, "The Myth ofthe Impotent Black Male," ibid., 2 (June 1971), 2-6; Alvin E Poussaint, "Blacks and the Sexual Revolution," Ebony, 26 (Oct. 1971), 112-13; Alvin E Poussaint, "Sex and the Black Male," ibid., 27 (Aug. 1972), 120; Daryl Michael Scott, Contempt and Pity: Social Policy and the Image ofthe Damaged Black Psyche, 1880-1996 (Chapel Hill, 1997), 150-56; Roderick A. Ferguson, Aberrations in Black: Toward a Queer of

- 40. Color Critique (Minneapolis, 2004), 124-25. Race and the Politics of Sexual Orientation in Philadelphia, 1969-1982 63 In a bizarre twist, one of the aides accused of molesting the youth was shot and killed by two unidentified assailants in what family members believed to be a revenge murder. The controversy spilled into the hearings on Bill 1275 when city council president Schwartz argued that passage of a sexual orientation law would require the city to implement psychiatric examinations "in connection with employees at the Youth Study Center," implicating rights claims with the sex scandal and pedophilia. The black press also ran sensational stories of prison sex and rape that stimulated even more black anxiety. Prison reform had become a major issue in African American politics, particularly after the 1971 riots at the Attica Correctional Facility in New York and at the Holmesburg Prison in Pennsylvania. A study of the riots at Holmesburg (reportedly perpetrated primarily by black prisoners) cited the facility's failure to implement a 1968 report that recommended more housing to remove sexual assaulters from the general population as well as immedi- ate, comprehensive physical examination of victims. The report concluded that the inci- dence of prison rape signaled a larger general failure of the guards to assure the safety of the entire prison community. So troubling was prison

- 41. homosexuality that reformers sought to propose more furloughs, probation, and prerelease programs in the name of curtailing its incidence, and studies also recommended the strict segregation of two groups—psychopaths and homosexuals—from the general prison population. At one point during the hearings, a former Holmesburg inmate testifying against the bill recounted that "one night a man came to me wanting to take my manhood from me. I got on my knees and I asked God to protect me." Testifying to his faith, he recalled "standing up on his feet and he had to sit back down, because greater is the spirit of God than any man." This supposedly proved that the council should reject the bill. In response, the chairman spoke of̂ the reasonableness of the sexually threatened man and declared that "many of you all back there . . . are against it. And it's up to you all."^^ In the face of testimony from these and other African American opponents, not only did the black co-sponsor of the bill, Charles Durham, speak only three times, and even then only on tangential issues, but Joseph Coleman appeared to drift from mild support in the name of civil rights toward opposition. Late in the hearings, Coleman created a justification for opposing the bill from the premises of the old argument often associated with the fear that removing legal barriers to integration led to indiscriminate mixing and even endangered young women. Confiasing the issue of homosexuality with cross-dressing, he projected a

- 42. scenario in which a "young lady" in a dressing room would be outraged by a "male hiding there masquerading." His assertion that the law would increase the incidence of unwitting " "vD, Homosexuality among Problems at Youth Study Center," Philadelphia Tribune, Oct. 30, 1973; "Homo- sexual Issues Spreads at Ysc as Six More Aides Are Arrested," ibid, Feb. 8, 1975; "YS.C. Aide in Homosexual Case Shot by 2 Gunmen," ibid., Feb. 25, 1975; "President Schwartz," I'cc Hearings on 1275, p. 315; "Sexual Parties Staged at Hall-Mercer Center," Philadelphia Tribune, March 8, 1975; "Racism Linked to Prison Brawl," New York Times, July 7, 1970, p. 32; "Gov. Shafer Asks Prison Take- Over," ibid., July 12, 1970, p. 33; "Task Force Fights Sex Violence in Pa. Prisons," Philadelphia Tribune, March 26, 1977; "PA. Prisons Head Blamed for Homosexual Assaults," ibid., Sept. 11, 1976; "Homosexual Attacks Are Serious Prison Problem," ibid., June 19, 1973; "Imple- mentation of the 1968 Recommendations," folder 24, box 24, Prisoner's Rights Council Papers (Paley Library); "Homosexuality Not Part of Rehab Program, State Prison Head Claims," Philadelphia Tribune, Aug. 12, 1976; "Women Inmates Say Brutal Gang Rapes Common at Muncy," ibid, Aug. 14, 1976; "Psychopaths, Homosexuals Are Causing Continuous Problems in Penna. Prispns," ibid, March 6, 1972; "Testimony of Wardell Lighty," KC Hearing on 1275, pp. 68-70; Heather Ann Thompson, "Why Mass Incarceration Matters: Rethinking Crisis, Decline, and Transformation in Postwar American History" Journal of American History, 97 (Dec. 2010), 703-58; Regina Kunzel, Criminal Intimacy: Prison and the Uneven History of Modem American Sexuality (Chicho, 2008).

- 43. 64 The Journal of American History June 2011 Brother Grant-Michael Fitzgerald, a black gay activist who testified before the Philadelphia city council in 1974, poses in a college class- room for a photo that was published in a history of his Catholic re- ligious order, the Society of the Divine Savior. Courtesy Society of the Divine Savior. males exposed to gay men was never explained. If the sexual orientation law passed, he wondered, how could heterosexuals contain the infiltration of homosexuals into everyday life? In his words, if "we pass this law, are we not unleashing upon not only women but men persons who have other sexual desires towards the individuals in their midst. Like a drop of black blood that threatened to mongrelize the nation, Coleman worried about containing the threat: we "are moving away from bathrooms and these kind of things to apartments."^' Only the testimony of Brother Grant-Michael Fitzgerald interrupted the apparent unity of the black witnesses. Born and raised in North Philadelphia, Fitzgerald had joined a Catholic religious order, the Society of the Divine Savior (SDS), in 1968 after he was fresh out of high school. At the time that he made his perpetual vows to poverty, chastity, and faith at the SDS headquarters in Milwaukee, he had come out as gay and joined the gay

- 44. liberation movement. He participated in the Milwaukee branch of the Council on Reli- gion and Homosexuality, the University of Wisconsin at Milwaukee's Gay People's Union, and appeared in a televised forum on homosexuality. When he returned to Philadelphia to testify for Bill 1275, he had honed an impressive arsenal of rhetorical weapons.^'* -̂' "Testimony of Joseph Coleman," I'cc Hearings on 1275, p. 280; "Ministers Differ on Gay Rights at Hearings on Bili to Ban Bias," Philadelphia Evening Bulletin, Jan. 28, 1975, p. 1. On Charies Durham, see George Corner, "The Black Coalition: An Experiment in Racial Cooperation in Philadelphia, 1968," Proceeding of the American Philosophical Society (]ine 15, 1976), 178-86. ^^ "No Room in the Inn?," Gay People's Union News, Dec. 1972, p. 9; Mike Hoffman to Kevin Mumford, e-mail, June 2, 2008 (in Mumford's possession); Gregory Baum, "Catholic Homosextials," Commonweal, 101 (Feb. 1974), 479-82; John A. Coleman, "The Churches and the Homosexual," America, Jan. 9, 1971, pp. 113-17; William J. Spangler, letter to the editor. Gay People's Union News, Feb. 1973, p. 6; Jefferson Keith interview by Mumford, Oct. 2007, transcript (in Mumford's possession). Race and the Politics of Sexual Orientation in Philadelphia, 1969-1982 65 In contrast to Coleman's formulation of the containment argument. Brother Fitzgerald retorted that he should have the personal right to "hold hands in public," explaining that

- 45. "black people can do that. Interracial couples can do that today." He invoked the civil rights movement, recounting his participation in the Poor People's Campaign of 1968, wearing it as a badge of authenticity. But these demonstrations had not fully expressed his complete identity and political objectives, and so he proclaimed, "I am also gay, and I want that to be part of the record. I am a born-again Christian who is black and is gay." Some members in the audience also became enraged when Brother Fitzgerald invoked his religious righteousness. A voice called out, "We're talking about sodomites," prompting Fitzgerald to compare the antigay terminology to racist epithets, arguing that it was acceptable to use one and not the other. In conclusion, Fitzgerald sought to demonstrate his respectability by blessing his gay brothers and sisters in the name of God.^' After the hearings were adjourned without a public vote, it was announced that Bill 1275 had died in committee. The press treated the hearings as a titillating story of gay witnesses and lurid questions, and readers of several papers could not have guessed that black religious opponents of the bill had even attended the hearings, much less forcefully argued against it. One article noted the opposition of firemen and police to the measure but made no reference to race. When articles talked of religious opposition, it was in terms of a "church-going woman" rather than black evangelicals. One journalist even reported that age divided the chambers and that the side

- 46. opposing gay rights "appeared older." The community press did not draw such conclusions. The black newspaper the Philadelphia Tribune reported on the human relations hearings that had convened in the summer, characterizing Rev. Melvin Floyd's moral attacks on gay rights as "absurd." In that sense, the Philadelphia Tribune had an on-and-off relationship with the gay commu- nity: on occasion it printed advertisements for gay and lesbian events and criticized some homophobic statements, but it also ran more antigay articles and columns than positive ones. In the gay press, the Philadelphia Weekly Gayzette pointed out that "the black fun- damentalist denominations sought strenuously and repeatedly to deny basic parallels between the gay movement and the black civil rights movement of the 50s and 60s," and that "blacks, in particular, insisted that while racial identity involves no choice on the part of the individual, sexual orientation is a subject of free will." Although gay activists later specifically approached black city council members to co- sponsor a new bill and in 1976 secured promises from black progressives, they remained largely silent about the racial fallout at the hearings on Bill 1275 and instead publicly blamed its failure on Council- man " "Testimony of Grant-Michael Fitzgerald," K:C Hearing on 1275, pp. 370, 368-69, 364, 369, 379, 373, 383, 381. "' "Clergy Flay, Defend Gays," Philadelphia Daily Neivs, Jan. 28, 1975, p. 5; "Gay Rights Bill Divides Church-

- 47. men," ibid., Dec. 19, 1974, p. 4; "Phila. Gays Confront Foes," Philadelphia Inquirer, Dec. 19, 1974, p. 2-B; "Schwartz Grills Segal about Gay Activists," Philadelphia Evening Bulletin, Dec. 19, 1974, p. 20; "Ministers Differ on Gay Rights at Hearing on Bill to Ban Bias," ibid., Dec. 28, 1975, p. 1; "Rev. Melvin Floyd Says 'Homosexuality Is Morally and Spiritually Wrong,' in Attacking Bill to Give Rights to Gays," Philadelphia Tribune, June 8, 1974; "Black Leaders Differ on 'Gay Rights' Bill," ibid., July 20, 1974, p. 3; "Council Hears Final Testimony; Vote Expected in Two Weeks," Philadelphia Weekly Gayzette, Jan. 31-Feb. 7, 1975, p. 4; "Cay Rights Bill Dies—Another in Preparation," Philadelphia Gay News, Jan. 3, 1976, p. 1; "New Phila. Gay Rights Bill to Be Introduced," ibid., Aug. 1976, p. A3; Garry Wills, "Both Sides Oversimplify Cay Rights Issue," Capital Times, June 8, 1977, file 7, box 1, United Papers (State Historical Society of Wisconsin, Madison). 66 The Journal of American History June 2011 Although two African American men—the chairman of the Human Relations Com- mission Clarence Farmer and the activist Brother Grant-Michael Fitzgerald—spoke elo- quently for the bill, they were drowned out by the many black voices against the measure, many white religious authorities, and members of the laity—all of whom turned out to challenge the ideas that gays were a real minority group and that prohibiting homophobia was a legitimate extension of the civil rights movement. If gay and lesbian activists had wished to forget the racial dynamics of their defeat, addressing

- 48. diversity within their movement and building cross-racial coalitions remained crucial to their success. Looking for the Intersection By the mid-1970s, the increasing number of gay and lesbian student organizations on college campuses (reportedly between 200 and 250) developed into a fresh source of organizing for legal reform. In 1972 a student group at Michigan State University helped pass the nation's first local measure banning employment discrimination in East Lansing, while one progressive college town after another (including Ann Arbor, Madison, and Iowa City) passed sexual orientation ordinances throughout the 1970s. Protections for sexual orientation were signed by mayors or passed by city councils in several cities with significant black populations, including Los Angeles, Detroit, and Washington, D.C. The struggle for passage of an ordinance in Philadelphia, with a black population that had increased from 33.6 percent to 37.8 percent over the decade, can be compared to the pat- terns in similar multiracial cities, such as New York and Chicago, with sexual orientation laws passed later. More than the local successes elsewhere, however, or the growth of gay politics on the national level (including attempts to pass an antidiscrimination measure in the House of Representatives and an employment measure in the Senate), it was the new visibility of the New Right that stimulated fresh activism in Philadelphia.'"

- 49. In 1977 the celebrity turned activist Anita Bryant organized Save Our Children to finance the repeal of a sexual orientation ordinance in Dade County, Florida, triggering successful repeal campaigns in Eugene, Oregon; St. Paul, Minnesota; and Wichita, Kan- sas, while activists fought back one in Seattle, Washington. Even progressive college towns felt the aftershocks of Bryant's activities: in Madison, the Reverend Wayne Dilla- baugh started a repeal campaign, but a group of gays and lesbians formed the United to "affirm" their "civil rights," forcing Dillabaugh to call off his campaign at a God and ^' "Homosexuals Gain Support on Campus," New York Times, June 5, 1974, p. 1 ; Beth Bailey, Sex in the Heart- land (Címhúá^t, Mass., 1997), 175-99; Brett Beemyn, "The Silence Is Broken: A History of the First Lesbian, Gay, and Bisexual College Student Gmyip^^' Journal of the History of Sexuality, 12 (April 2003), 205-23. On the East Lansing ordinance, see "Human Relations Commission Needs to Come into Focus," East Lansing Towne Gourier, April 12, 1972; "Midwest City Votes Job Equality for Gays, East Lansing Mich. 1st in Nation," Gv4K May 1, 1972, p. 1. On student politics and gay liberation, see Anthony Ralph Smith, "College Town Radicals: The Case of the Ann Arbor Human Rights Party" (Ph.D. diss.. University of Illinois, 1980), 118-20, 91-92, 203-4, 208-10, 212-14, 227-28. Madison, Wis., Ordinance 4923 (March 11, 1975); Paul Soglin to Mumford, e-mail, Aug. 2008 (in Mumford's possession); Iowa Ciry, Iowa, Code 77-2830 (1977). On the Washington, D . C , ordinance, see Valk, Radical Sisters, 147. Washington, D . C , Ordinance 75-230 (Oct. 31, 1975). On the Detroit ordinance, see Van der

- 50. Meide, Legislating Equality, 59-60. On the Los Angeles ordinance, see Self, "Sex in the Ciry," 309-11. On the antidiscrimination measure in the House of Representatives, see "Homosexual Rights Measure Introduced by 24 in House," New York Times, March 26, 1975, p. 6. On the Senate bill, see Bulletin of the Philadelphia Lesbian and Gay Task Force, 4 (no. 2, 1976), 1, folder 4, box 16, Christian Association Papers (University Archives and Récordes Center, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia). Kenneth D. Wald, James W. Button, and Barbara A. Rienzo, All Politics Is Local: Analyzing Local Gay Rights Legislation (Washington, 1997). Race and the Politics of Sexual Orientation in Philadelphia, 1969-1982 67 Decency Rally attended by approximately 150 people. Though religious rhetoric infused the backlash, it remained intertwined with the argument that sexual orientation was not like race. In her memoir, Anita Bryant recited the Bible repeatedly but also stressed that she taught her children never to discriminate against "anyone because of their race or religion." At another point, she cited editorials in black newspapers to prove that "the we-are-birds-of-a-feather appeal to the blacks by the homosexuals was soundly rejected."'̂ ^ Bryant's success signaled a clear rightward political drift throughout the 1970s, but lib- eral institutions and radical communities also survived. Philadelphia feminists sustained groups such as Dyketactics, which had disrupted the

- 51. proceedings of the city council to protest the failure of Bill 1275—an action for which they were violently arrested. Another leftist group, the Philadelphia Reproductive Rights Organization, joined to support a new gay rights bill. Antirape advocates engaged in dialogue with prisoners' rights groups, and Planned Parenthood as well as the Urban League addressed issues of race and sexuality, including teenage pregnancy and reproductive control. Throughout the 1970s the number of gay and lesbian bars and dance clubs began to peak, including more than a dozen black gay bars. Finally, just as so many of the initiatives for antidiscrimination ordinances suc- ceeded in college towns, the gay rights movement in Philadelphia reignited at the University of Pennsylvania. In 1975 a number of students and staff had formed Gays at Penn and a gay peer counseling service, both of which received funding from the Christian Association, a nondenominational philanthropic organization on campus. An "Answer Anita" meeting was advertised at the Christian Association and the organization's annual report observed that Gays at Penn had entered "into a new phase, emphasizing activism and visibility."^'' In turn, conservatives on campus fought back with mockery and physical confronta- tion that opened the floodgates of reform. In the spring semester of 1978, a fraternity sponsored an initiation rite in which pledges posed as pollsters and asked passersby if they preferred homosexuality, while some members reportedly yelled gay slogans and epithets