1 The Art of Facilitating Language Learning (AFLL) Course Resource Book

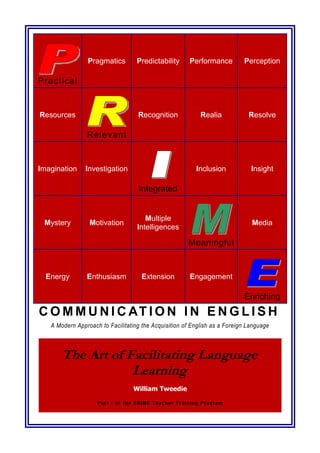

- 1. Pragmatics Predictability Performance Perception Practical Resources Recognition Realia Resolve Relevant Imagination Investigation Inclusion Insight Integrated Multiple Mystery Motivation Media Intelligences Meaningful Energy Enthusiasm Extension Engagement Enriching C O M M U N I C AT I O N I N E N G L I S H A Modern Approach to Facilitating the Acquisition of English as a Foreign Language The Art of Facilitating Language Learning William Tweedie Part 1 of the PRIME Teacher Training Program

- 2. The Art of Facilitating Language Learning Introduction to the PRIME© Approach and Method For English Language Acquisition Facilitation Course Reference Book William Tweedie © 2005 - 2010 Kenmac Educan International & William M Tweedie 2

- 3. TABLE OF CONTENTS THE ART OF FACILITATING LANGUAGE LEARNING..........................................................................................2 INTRODUCTION TO THE PRIME© APPROACH AND METHOD..........................................................................2 FOR ENGLISH LANGUAGE ACQUISITION FACILITATION...................................................................................2 COURSE OUTLINE..........................................................................................................................................5 KEY PRINCIPLES OF THE PRIME© APPROACH AND METHOD..........................................................................6 THE DIMENSIONS OF LEARNING......................................................................................................................................7 PRIME© CLASSROOM TIPS..........................................................................................................................15 THE ART AND CRAFT OF MOTIVATING STUDENTS .......................................................................................16 LIZ REGAN'S 20 TEACHING TIPS...................................................................................................................18 TEACHING TIP 1: PAIR WORK / GROUP WORK.............................................................................................18 TEACHING TIP 2: READING ALOUD...............................................................................................................19 TEACHING TIP 3: CHECKING UNDERSTANDING.............................................................................................20 TEACHING TIP 4: PRONUNCIATION..............................................................................................................20 TEACHING TIP 5: SPEAKING TO OTHER STUDENTS IN ENGLISH.....................................................................21 TEACHING TIP 6: GUESSING ANSWERS.........................................................................................................22 TEACHING TIP 7: STOPPING AN ACTIVITY.....................................................................................................23 TEACHING TIP 8: FEEDBACK.........................................................................................................................24 TEACHING TIP 9: DEALING WITH VOCABULARY QUERIES.............................................................................25 TEACHING TIP 10: MONITORING.................................................................................................................26 TEACHING TIP 11: ERROR CORRECTION.......................................................................................................27 TEACHING TIP 12: ELICITING........................................................................................................................28 TEACHING TIP 13: CHECKING TOGETHER......................................................................................................28 TEACHING TIP 14: READING BEFORE WRITING.............................................................................................29 TEACHING TIP 15: BRAINSTORMING............................................................................................................30 TEACHING TIP 16: PERSONALISING..............................................................................................................30 TEACHING TIP 17: TRANSLATING.................................................................................................................31 TEACHING TIP 18: PACING...........................................................................................................................32 TEACHING TIP 19: CONCEPT CHECKING........................................................................................................33 TEACHING TIP 20: USING DICTIONARIES......................................................................................................33 WHAT DOES A GREAT LESSON LOOK LIKE? ..................................................................................................35 CHARACTERISTICS OF EFFECTIVE TEACHING.................................................................................................36 ENTHUSIASM RATING.................................................................................................................................39 DEGREE OF PERFORMANCE.........................................................................................................................39 OVERVIEW OF SELECTED CLASSROOM STRUCTURES....................................................................................43 THE TEACHER'S USE OF LANGUAGE ............................................................................................................45 CONTEXTUAL SUPPORTS FOR LINGUISTIC DEVELOPMENT ...........................................................................46 3

- 4. QUOTATIONS TO INSPIRE............................................................................................................................48 …. ..............................................................................................................................................................49 …. ..............................................................................................................................................................50 …. ..............................................................................................................................................................51 …. ..............................................................................................................................................................52 Articles are the property of the authors and copyright owners. Permission is granted for reproduction. Please cite the authors and source. 4

- 5. Course Outline The Art of Facilitating Learning Developed and Presented by William M. Tweedie A) What Is Language? B) The Nature Of Language As A Means Of Communication 1) Communicating Is A Creative, Imaginative Act (a) Thinking And Writing Individual Activity C) Learning and Teaching as Communication - The Practical Purposes D) What Are The Practical Purposes Of Communication? 1) The Models Of Language Use - Real Needs And Wants Defined And Categorized (a) Small Group Brainstorming and Categorizing Activity E) How Important Are Practical Purposes In Facilitating Learning? (a) “I Have To Do This.” Vs. “I Want To Do This.” - Whole Group Discussion F) Relevance And Learning G) Learning Vs. Acquiring A Language - Purposeful Language Is Acquired 1) Sequencing And Ranking Practical Purposes In Terms Of Relevance (a) Small Group And Group Reporting Activity H) How Effectively Do Contemporary Textbooks Provide Opportunities For Practical And Relevant Use Of The English Language? How Can We Make The Textbooks Relevant? 1) An Introduction To The Seven Levels Of Engagement 2) Engaging The Imagination And Providing Opportunities For Real Use Of Language (a) An Introduction To Theme Webbing And Project Based Learning (i) Video Presentation And Small Group Webbing Activity II) How Do We Facilitate Learning? Integrated Means… A) The Human Means Of Communicating 1) Whole Group Brainstorming And Categorizing Activity B) How Can The Means Of Communication Help Facilitate ELA? 1) Small Group Integrated Interactive Activity III) What Do We Communicate? Meaning Means… A) The Meaningful Nature Of Language 1) Accuracy And Fluency – “The Chicken Or The Egg” (a) Demonstration Of The ‘Echo’ And ‘Backward Build-Up’ Techniques IV) Education - an Engaging and Enriching Process of Discovery 5

- 6. A) Learning Enrich Lives and The Global Community Key Principles of the PRIME© Approach and Method By William M. Tweedie Communication is the primary goal in the facilitation of English Language Acquisition. The implications take us beyond the accepted axiom that we should teach language usage, not about the language. English, like all human languages, has one general purpose, which is to convey our thoughts and feelings to other beings, to communicate. English is not the end. It is one means to the end. Communication is PRACTICAL. People communicate for specific, identifiable purposes. We need to know and understand why people communicate and how English can be used as one means to accomplish these purposes. Human communication exists when intelligible signals are transmitted and received in the context of the satisfaction of needs and wants, fulfilling purposes. All else is communicatively useless action or noise. Students acquire English if it is RELEVANT to their lives, that is, if it satisfies real needs and wants, involves them as individuals, addressing their backgrounds, interests, and goals. The choice of language used in oral and written communication involves interactional uncertainty. The language used in communication is, largely, unpredictable. Providing students with strategies to manage this uncertainty and the unpredictability in discourse is essential to building beginners’ confidence and sustaining their motivation. Communication is accomplished through a variety of INTEGRATED means that should not be isolated in the learning/acquisition process. Observation takes its rightful place as an essential skill along with Listening, Reading, Speaking, and Writing. All other motional and emotional means of communication figure importantly in the process. Beginners need as many options as possible to support their efforts to communicate. All communication options should be explored before resorting to their native language and translation. Communication is context dependent, must be comprehensible, and MEANINGFUL to both sender and receiver. Facilitators must ensure that their communication with students and the language students are engaged in acquiring are both comprehensible and meaningful and that the understanding and conveyance of meaning takes precedence over correctness of form, content, and structure. The most important criteria in assessing students’ progress are first, the degree to which the student is actively engaged in the process of English language acquisition and secondly, how effectively s/he comprehends, negotiates, and conveys meaning, not the correctness of form or grammar. Facilitators of language acquisition have the responsibility of providing students with the tools necessary for progress. These include an array of strategies for learning in general and language learning specifically. Language learning strategies, direct and indirect, must be incorporated into the curriculum. Students will acquire the English they want and agree they need to. Therefore, Students must first Initiate, then Direct, Control, Monitor, and Evaluate (SIDCME) their own learning (The PRIME© METHOD). Facilitators provide the framework and guideposts, students provide the substance. The most significant implication of this principle is in the facilitator’s acceptance of the role as ‘guide on the side, not sage on the stage’. To achieve the objective of students becoming autonomous learners, the facilitator must have patience, resolve and be flexible, resourceful, engaging (motivating) and enriching (FREE) in taking this Approach. 6

- 7. Language acquisition is an indefinite process with characteristics distinct from other subject matter learning. The psychological and emotional factors in language acquisition must figure largely in the approach facilitators and students take to the process because communication is the expression of self, one’s identity, in the process of fulfilling its purposes. Students cannot be expected to achieve goals set out on a continuum of grammatical structures, forms, and functions. The content they need and want to express in achieving relevant purposes will require different and varied structures and forms at different times. The facilitator must have sufficient command and knowledge of English usage to be an effective model for the students and provider of the information they need. The facilitator’s language and classroom material are known and perceived by the students to be models for their own language development. The process must be enjoyable and ENRICHING to self and society. Is it not our ultimate goal, as facilitators of the acquisition of language for its practical use in achieving meaningful purposes, to help people understand each other so they can help each other progress towards a better world? This principle will guide facilitators and students in the selection or development of material for classroom modeling and practising. Language acquisition is a process tangent to and reflective of the student’s development and growth across all the dimensions of learning. The next section takes a closer look at this important concept. The Dimensions of Learning ESL standards articulated by such organizations as TESOL, USA and most commercial ESL programmes pay little attention to the progress of students across all the dimensions of learning. It is important that the facilitators be aware of the students’ progress along these dimensions as it is likely they correlate directly to their progress in the acquisition process.1 The dimensions of learning commonly articulated are: 1. Confidence and Independence 2. Skills and Strategies 3. Knowledge and Understanding 4. Use of Prior and Emerging Experience 5. Reflection - Contemplative and Critical ‘Learning occurs across complex dimensions that are interrelated and interdependent. Learning theorists have argued that learning and development are not components of an assembly line that can be broken down into discrete steps occurring with machine-time precision, but an organic PROCESS that unfolds along a continuum according to its own pace and rhythm. The facilitator/facilitator and student should be actively searching for, and documenting positive evidence of the student’s development across the five dimensions listed above. These five dimensions cannot be separated out and treated individually; rather, they are dynamically interwoven and interdependent.’ (Iverson, S) Confidence and Independence Growth and development occur when learners’ confidence and independence become coordinated with their actual abilities and skills, content knowledge, use of their experience, and reflective of their own learning. It is not a simple case of ‘more is better’. The overconfident student, who has relied on faulty or underdeveloped skills and strategies, learns to ask for help when facing an obstacle; the shy student begins to trust his/her own abilities and begins to work alone at times, or to insist on presenting her own point of view in discussions. In both cases, students develop along the dimension of confidence and independence. Skills and Strategies Specific skills and strategies are involved in the process of language acquisition as well as other areas of learning that require instruction and the active participation of the students. These skills 1 While great progress has been made in expanding the scope of factors that affect ELA facilitation in recent years such as Multiple Intelligence and Thinking Styles Theories, there is a need for more research of the relationships among emotion, the psychology of learning, and language acquisition. 7

- 8. include technological skills for computer communication for all students if they are to become active participants in the global village. ‘Skills and strategies represent the “know-how” aspect of learning.’ How well students actually learn (performance ability or mastery of any given content ) or acquire, in the context of second language acquisition, depends on how well they know and use the skills and strategies laid open to them for their personal use. Knowledge and Understanding Content knowledge refers to the extent students understand the theory of new or revealed methods, techniques, and topics and the relationship between theories and practise. It is measured by how effectively the knowledge (ideas) is conveyed by facilitators of learning as well as by how well students demonstrate their understanding of the ideas through formal and informal presentations (examinations, writings, practical and relevant use of the knowledge). This dimension of learning is the most familiar as it has been the most quantifiable and justifiable in terms of historically modern educational systems. What is the simple past of the verb ‘to think’? What is a “web site” on the World- Wide Web? These are typical content knowledge/understanding questions. Use of Prior and Emerging Experience Use of prior and emerging experience involves the students’ awareness of the importance and relevance of their own experience, the ability to draw on this experience and connect it to their engagement in the process of learning. ‘A crucial but often unrecognized dimension of learning is the ability to make use of prior experience in new situations’ or when confronted with new learning challenges. It is necessary to overtly encourage and value learners’ experiences and more over to help them incorporate their experiences into the process of learning and acquiring a new language in that case. ‘Observing learners over a period of time as they are engaged in a variety of activities will allow this important capability to be accounted for.’ This dimension of learning is, after all, at the heart of new imaginings and their realization. In structured, inflexible, predetermined curricula we cannot discover, nor can the student, how his/her prior experience might help build new or greater understandings, or how ongoing experience shapes the content knowledge and understanding, skills and strategies, indeed, the confidence and independence he/she is developing. Imagine you have no imagination. Reflection - Contemplative and Critical It is important to contemplate our own learning process and to analyse how we are progressing in the process of acquiring our knowledge or a second language. How well are we using the skills and strategies available to us to communicate better our thoughts and feelings? Are our students and we developing the ability to distance ourselves enough from the process to reflect on it in the general terms of the extent we are engaged in it and how important it is to our development as human beings and as a global society? Is our ability to think critically of the specific aspects of the process, i.e., how well we using the skills and strategies we need? How much effort are we putting into developing our confidence? How courageous are we becoming in validating our own experiences and using them to build our futures on? This overview thinking and recognition of limitations and obstacles provides the impetus for continued progress and is a necessary dimension of learning and acquisition of language for stronger, clearer communication. (Source: Adapted from Sue Iverson for original Facilitator Training Workshops by J.W.M. Tweedie)2 Facilitators in this programme must monitor all the factors articulated because language cannot be acquired effectively without the management of and accomplishment in these areas. While students are expected to achieve some of these minimum standards or learning outcomes, their efforts and progress should be the most important factor in assessments and evaluations, not the quality or quantity of English they have acquired. This is according to the unique nature of second language acquisition. 2 Sue Iverson introduced the concepts of the five dimensions for the University of Texas in 1997 for general learning. I have adapted and related them specifically to the arena of second language acquisition. 8

- 9. PRIME© Principles in Action in the Classroom By William M. Tweedie Adapted From the NCBE Program Information Guide Series, Number 19 Silence is often needed Students must be silent at times as they learn to speak a second language. Some learners need to focus more on listening than speaking, especially during the early stages of learning and acquiring a new language. For others, there may be a need to briefly "tune out" at points in the course of a day to "recharge" from the constant effort of listening and speaking in a new language. Silence may also occur in extended pauses before a student answers a question. Allow students additional time to collect their thoughts and structure their answer. Moving too quickly to the next student discourages efforts to respond; in contrast, recognizing that the student needs more time to answer lets the student know that you are interested in listening. Errors generally indicate progress As with first language acquisition, errors can actually have a positive meaning. They often appear when a learner is trying out new grammatical structures. When the focus is on communicating, direct correction of errors can hinder students' efforts and discourage further attempts to express ideas with the language skills they have available. Rather than correct errors directly, a teacher can continue the dialogue by restating what the student has said to model the correct form. Valuing diversity Valuing the diverse backgrounds and resources that EFL students bring to the classroom and being sensitive to their unique needs can serve to build an instructional environment that can benefit all students. Current education research and reform focus on increasing student participation in instruction and on basing instruction on the real-life needs of students. An active learning and acquiring instructional model for EFL students includes elements that address the special language-related needs of students who are learning and acquiring English. Instructional content should utilize student diversity. Incorporating diversity into the classroom provides EFL students with social support, offers all students opportunities to recognize and validate different perspectives, and provides all students interesting information. Also, examples and information relevant to EFL students' backgrounds assist them in understanding content. Increasing comfort levels The classroom should be predictable and accepting of all students. All students are able to focus on and enjoy learning and acquiring more when the school and classroom make them feel safe - comfortable with themselves and with their surroundings. Teachers can increase comfort levels through structured classroom rules and activity patterns, explicit expectations, and genuine care and concern for each student. Instructional activities should maximize opportunities for communication and as much as possible, language use. Opportunities for substantive, sustained dialogue are critical to challenging students' abilities to communicate ideas, formulate questions, and use language for higher order thinking. Each student, at his or her own level of proficiency, should have opportunities to communicate meaningfully in this way. 9

- 10. Involving students Instructional tasks should involve students as active participants. Students contribute and learn more effectively when they are able to play a role in structuring their own learning and acquiring, when tasks are oriented toward discovery of concepts and answers to questions, and when the content is both meaningful and challenging. Instructional interactions should provide support for student understanding. Teachers should ensure that students understand the concepts and materials being presented. For EFL students this includes providing support for the students' understanding of instruction presented in English. Creating an accepting and predictable environment A supportive environment is built by the teacher on several grounds. There is acceptance, interest, and understanding of different backgrounds, beliefs, and learning styles or Multiple Intelligences. Explicit information on what is expected of students is provided and is reinforced through clearly structured daily patterns and class activities. These provide important social and practical bases for students, especially EFL students. When students are freed of the need to interpret expectations and figure out task structures, they can concentrate on and take risks in learning and acquiring. Provide a clear acceptance of each student. Maximizing opportunities for language use Communication in all its aspects, i.e., observing, listening, reading, writing, and all other means, including oral expression, is really central to learning and acquiring for all EFL students. Through experience in trying to express ideas, formulate questions, and explain solutions, students' use of their native as well as English language and other communication skills, supports their development of higher order thinking skills. The following points are important ways to maximize language use. (i) Ask questions that require new or extended responses. b) The teacher's questions should elicit new knowledge, new responses, and thoughtful efforts from students. They should require answers that go beyond a single word or predictable patterns. Students can be asked to expand on their answers by giving reasons why they believe a particular response is correct, by explaining how they arrived at a particular conclusion, or by expanding upon a particular response by creating a logical follow-on statement. (i) Create opportunities for sustained dialogue and substantive language use. c) It is often hard to give many students the opportunities needed for meaningful, sustained dialogue within a teacher-centered instructional activity. To maximize opportunities for students to use language, teachers can plan to include other ways of organizing learning and acquiring activities. For example, in cooperative learning and acquiring groups, students use language together to accomplish academic tasks. In reciprocal teaching models, each student/group is responsible for completing then sharing/teaching one portion of a given task. d) Opportunities for maximizing language use and engaging in a sustained dialogue should occur in both written and oral English. Students can write in daily journals, seen by only themselves and the teacher. This type of writing should be encouraged for students at all levels. Some EFL students may be too embarrassed to write at first; they may be afraid of not writing everything correctly. The focus in this type of writing, however, should be on communicating. Students should be given opportunities to write about what they have observed or learned. Less English proficient EFL students can be paired to work with other, more proficient students or be encouraged to include illustrations, for example, when they report their observations. e) The teacher should also ensure that there are substantive opportunities for students to use oral and written language to define, summarize, and report on activities. Learning and acquiring takes place often through students' efforts to summarize what they have observed, explain their ideas about a topic to others, and answer questions about their presentations. EFL students' language proficiency may not be fully equal to the task; however, they should 10

- 11. be encouraged to present their ideas using the oral, written, and non-linguistic communication skills they do have. This can be supplemented through small group work where students learn from each other as they record observations and prepare oral presentations. (i) Provide opportunities for language use in multiple settings. f) Opportunities for meaningful language use should be provided in a variety of situations: small groups, with a variety of groupings (i.e., in terms of English proficiency); peer-peer dyads (again, with a variety of groupings); and teacher-student dyads. Each situation will place its own demands on students and expose them to varied types of language use. g) The physical layout of the room should be structured to support flexible interaction among students. There can be activity areas where students can meet in small groups or the teacher can meet with a student, or the furniture in the room can be arranged and rearranged to match the needs of an activity. (i) Focus on communication. h) When the focus is on communicating or discussing ideas, specific error correction should be given a minor role. This does not mean that errors are never corrected; it means that this should be done as a specific editing step, apart from the actual production of the written piece. Similarly, in oral language use, constant, insistent correction of errors will discourage EFL students from using language to communicate. Indirect modeling (echoing) of a corrected form in the context of a response is preferable to direct correction. (i) Provide for active participation in meaningful and challenging tasks. i) Shifts in approach, that recent research and reform efforts indicate are effective for all students, are especially necessary in EFL contexts. For example, many descriptions of instructional innovation focus on increasing student participation in ways that result in students asking questions and constructing knowledge, through a process of discovery to arrive at new information that is meaningful and that expands students knowledge. An important goal is to create or increase the level of "authentic" (Newmann and Wehlage, 1993) instruction, i.e., instruction that results in learning and acquiring that is relevant and meaningful beyond success in the classroom task alone. (i) Give students responsibility for their own learning and acquiring. j) In active participation, students assist the teacher in defining the goals of instruction and identifying specific content to be examined or questions to be addressed. Students also play active roles in developing the knowledge that is to be learned (e.g., students observe and report on what they have observed, write to organizations for needed information, and assist each other in interpreting and summarizing information). Active participation also involves some shifting of roles and responsibilities; teachers become less directive and more facilitative, while students assume increasing responsibility. k) EFL students need to participate. Their participation can be at a level that is less demanding linguistically, but still requires higher order thinking skills and allows them to demonstrate or provide information in non-linguistic ways. For example, using limited written text, an EFL student with very little oral or written proficiency in English can create a pictorial record of what was observed in a science class, noting important differences from one event to the next. (i) Develop the use of a discovery process. l) When students take an active role in constructing new knowledge, they use what they already know to identify questions and seek new answers. A discovery process is one in which students participate in defining the questions to be asked, develop hypotheses about the answers, work together to define ways to obtain the information they need to test their 11

- 12. hypotheses, gather information, and summarize and interpret their findings. Through these steps, students learn new content in a way that allows them to build ownership of what they are learning and acquiring. They are also learning and acquiring how to learn and acquire. (i) Include the use of cooperative student efforts. m) Recent findings about how people learn emphasize the social nature of learning and acquiring. Many successful examples of classroom innovation with EFL students show the value of using cooperative working groups composed of heterogeneous groups of students, including students at different levels of ability. The composition of groups should be carefully considered and should be flexible so that students experience working with different individuals. Mixing less English proficient EFL and more English proficient students within groups promotes opportunities to hear and use English within a meaningful, goal-directed context. n) Learning to work in cooperative groups requires practice and guidance for the students. Formal roles should be assigned to each member of a group (e.g., note-taker, reporter, group discussion leader), and these roles should be rotated. At older grades, as students identify different tasks to be accomplished by a group, students might define and assign their own responsibilities. In all cases, the use of group work requires attention to ensure that each individual has opportunities and responsibilities in contributing to the development of the overall product. Teachers need to be sensitive to the fact that some students prefer independent rather than cooperative learning and acquiring structures and activities. Teachers may want to consider adjusting the balance of learning and acquiring activities for students to accommodate such differences and to provide more support, thereby allowing students to gradually become more comfortable in these activities. (i) Make learning and acquiring relevant to the students' experience. o) Content matter is more meaningful for students when it relates to their background and experience. Furthermore, new knowledge is best learned and retained when it can be linked to existing "funds of knowledge" (Moll et al. 1990) so new content should be introduced through its relationship to an already understood concept. For example, a discussion of food cycles can begin with a discussion of foods commonly found in students' homes and communities. p) It is important that the learning experience regularly draws links between home, the community, and the classroom because this serves to contextualize and make content meaningful for students and ultimately to better acquisition of English. An active learning and acquiring instructional approach ultimately seeks to develop in students a view of themselves as learners in all aspects of their lives, not only in the classroom. Students should see opportunities and resources for learning and acquiring outside of the classroom as well. Whenever possible, the resources of the home and community should be used. For example, when a class is learning about structure, a parent who is a carpenter can be called upon to explain how the use of different materials can affect the design and strength of a structure (taking into account function, strength, flexibility, and so on). (i) Use thematic integration of content across subject areas. q) Learning and acquiring is also made more meaningful when it is contextualized within a broader topic. Business administration, Telecommunications, and Information Technology can all become interrelated through their common reference to the same theme or topic of interest just as Maintenance, Production processes, and Food Technology can (or any combination for that matter). In this way different perspectives on the topic are developed through linkages across different types of learning and acquiring activities. (i) Build in-depth investigation of content. 12

- 13. r) Instruction is more challenging and engaging when it provides in-depth examination of fewer topics rather than more limited coverage of a broader range of topics. Furthermore, a comprehensive exploration of one or more content areas promotes understanding and helps students retain what they learn. Also, integrated, thematic curricula that address the same topic across different content areas provide students opportunities to explore a given subject in greater depth. (i) Design activities that promote higher order thinking skills. s) Classroom tasks should challenge students by requiring them to develop and utilize higher order skills. Higher order thinking activities require students to use what they know to generate new information (e.g., to solve problems, integrate information, or compare and contrast). Higher order skills are utilized, for example, when students are asked to review a folktale from one country that they have just read, to identify another folktale from their own background that they think makes a similar point, and to explain the similarities and differences. This is in contrast to lower order thinking skills such as rote repetition of responses or memorization of facts. (i) Provide support for understanding. t) Students need opportunities to take responsibility for their own learning and acquiring - to seek out information and formulate answers. This is what the active learning and acquiring instructional model provides. However, essential to the process, is the support provided by the teacher. As a partner in students' investigations of new content, the teacher should guide and facilitate students' efforts. u) The teacher's input as a facilitator and guide to students should be carried out in a variety of ways, such as: i) asking open-ended questions that invite comparison and contrast, and prompt students to integrate what they have observed, draw conclusions, or state hypotheses; ii) assisting students in identifying needed resources, including setting up linkages with resources in the local community (e.g., local experts who could visit, field trips to organizations, and so on); iii) structuring learning and acquiring activities that require students to work cooperatively, modeling the different group member roles if necessary; iv) encouraging students to discuss concepts they are learning, to share their thoughts, and to express further questions that they would like to tackle; v) establishing long-term dialogues with students about the work they are doing, either in regular teacher/student conferences or dialogue journals; and vi) setting up opportunities for students to demonstrate or exhibit their work to other classes in the school as a means of prompting further dialogue outside of the classroom (i) Work together with others. v) The attempt to restructure activities in your classroom and to deal with new forms of diversity is a challenging one. It is not one that a teacher needs to face alone. Combine your expertise with that of other teachers. w) A significant body of recent research has focused on the value of teachers combining their professional expertise and sharing their experiences with one another. Teachers can offer important support to each other by serving as sounding boards for successes and failures, as additional sources of suggestions for resolving problem situations, and as resources to each other in sharing ideas, materials, and successful practices. Also, the more teachers who work with the same students share information, the more consistent and effective their students' overall instructional experience will be. x) Teachers should take steps to: i) collaborate and confer with EFL specialists; 13

- 14. ii) collaborate with other content area teachers who work with the same EFL students to share resources, ideas, and information about students' work; iii) share ideas and experiences with teachers who are interested in trying out more active instructional activities with their students; iv) involve the program director; let him know what you are doing; explain how you are implementing an active instructional model in your class, and the benefits for the students. Ask for support; some of this support should come in tangible ways, such as assistance in scheduling joint planning periods or in-class sessions in co-teaching or straightforward observation. YOU CAN'T DO IT ALL AT ONCE If you are interested in moving toward an active learning and acquiring instructional model, starting small is okay. Begin by becoming more familiar with your students. Perhaps set up a regular time with each for discussion. Learn about models for cooperative group work and plan to try cooperative work for one specific type of activity on a regular basis. Talk with other teachers and develop ideas together. Step by step you will be able to build an active learning and acquiring approach that will benefit all students in your classroom. REFERENCES COLLIER, V. (1989). HOW LONG: A SYNTHESIS OF RESEARCH ON ACADEMIC ACHIEVEMENT IN A SECOND LANGUAGE. TESOL QUARTERLY, 23, 509-531. FATHMAN, A. K., QUINN, M. E., AND KESSLER. (1992). TEACHING SCIENCE TO ENGLISH LEARNERS, GRADES 4-8. NATIONAL CLEARINGHOUSE FOR BILINGUAL EDUCATION, PROGRAM INFORMATION GUIDE SERIES, NO. 11. WASHINGTON, D.C.: NATIONAL CLEARINGHOUSE FOR BILINGUAL EDUCATION. KOBER, N., EDTALK: WHAT WE KNOW ABOUT SCIENCE TEACHING AND LEARNING AND ACQUIRING. WASHINGTON, D.C.: COUNCIL FOR EDUCATIONAL DEVELOPMENT AND RESEARCH. MCLAUGHLIN, B. (1992). MYTHS AND MISCONCEPTIONS ABOUT SECOND LANGUAGE LEARNING AND ACQUIRING: WHAT EVERY TEACHER NEEDS TO UNLEARN. NATIONAL CENTER FOR RESEARCH ON CULTURAL DIVERSITY AND SECOND LANGUAGE LEARNING AND ACQUIRING. WASHINGTON, D.C.: CENTER FOR APPLIED LINGUISTICS. MOLL, L., VELEZ-IBANEZ, C., AND GREENBERG, J. (1990). COMMUNITY KNOWLEDGE AND CLASSROOM PRACTICE: COMBINING RESOURCES FOR LITERACY INSTRUCTION. HANDBOOK FOR TEACHERS AND PLANNERS. INNOVATIVE APPROACHES RESEARCH PROJECT. ARLINGTON, VA: DEVELOPMENT ASSOCIATES, INC. NEWMANN, F. M., AND WEHLAGE, G. G. (1993). FIVE STANDARDS OF AUTHENTIC INSTRUCTION. EDUCATIONAL LEADERSHIP, 50, 7, APRIL, 8-12. LATRHOP, L., VINCENT, C., AND ZEHLER, A. M. (1993). SPECIAL ISSUES ANALYSIS CENTER FOCUS GROUP REPORT: ACTIVE LEARNING AND ACQUIRING INSTRUCTIONAL MODELS FOR LIMITED ENGLISH PROFICIENT STUDENTS. REPORT TO U.S. DEPARTMENT OF EDUCATION, OFFICE OF BILINGUAL EDUCATION AND MINORITY LANGUAGES AFFAIRS (OBEMLA). ARLINGTON, VA: DEVELOPMENT ASSOCIATES, INC. Warren, B., and Rosebery, A. (1990). Cheche Konnen: Collaborative scientific inquiry in language minority classrooms. Technical Report from the Innovative Approaches Research Project. Arlington, VA: Development Associates, Inc. Naturally and obviously, the suggested activities described in this resource book must be modified or adapted for the students’ levels of ability. 14

- 15. PRIME Classroom Tips © By William M. Tweedie 1. Give regular attention to each student or group of students and to individual students with exceptional needs. Set a timer to ring at 5 - 10 minute intervals if possible. 2. Choose students in each class for classroom management tasks every two weeks or so. For example, cleaning the board, straightening up tables, organizing file boxes, watering plants, caring for special projects, distributing supplies, etc. Occasionally, make this a class activity. 3. Give directions clearly, shorten and rephrase if not understood, give visual clues as often as possible. 4. Do not ask rhetorical questions. (Can the ‘can you…’ questions.) Be declarative. Teach before you test! 5. Praise good listening – often. Give specific, meaningful affirmations. Watch out for the slip-ups like “Well, it’s about time!” There are at least 102 ways to say “Good job!” 6. Give a student a partner who can help them whenever possible. 7. Do not make students recopy written work. Have them read it to you (or another student) instead and have them practice with writing worksheets at home. 8. Arrange the class to minimize distractions. Keep regularly used materials in the same location. Use labels and signs as much as possible. 9. Encourage students to use a tape recorder for recording the teacher’s, their own or other students’ use of English. 10. Do not call on a student who is not ready or prepared (academically, psychologically or otherwise) to answer questions, read aloud, or otherwise respond or participate. Spread the participation among those who are ready. Do not be afraid to ask a student “Are you ready?” They will respond honestly if they know they will not be ridiculed or pressured – by you or by other students. Let students know in advance that they will be called upon during class whenever possible. A student’s readiness can be checked and encouraged this way. Write out lesson questions beforehand, whenever possible, to allow students to better prepare their answers. 11. Post the class rules and expectations and have the class discuss them (in the first lesson ideally) to ensure agreement and understanding. Be thorough. Cover all aspects of classroom behaviour. Model the behaviour. (Discuss entering and leaving the class (when and how); requesting permission to leave the class for washroom, illness or other reasons; procedural and organizational considerations; homework and class work submissions – include name and number in top right hand corner, for example; classroom duties; etc.) 12. If possible, videotape your class to monitor your and the students’ behaviour. Share the results with the class or use it to help individual students with behaviour or instruction/content problems. 15

- 16. The Art and Craft of Motivating Students Control, Competency, and Connection By Diane Walker - Updated by Melissa Kelly The educational equivalent to "location, location, location," is "motivation, motivation, motivation," for motivation is probably the most significant factor educators can target in order to improve learning. Teachers routinely attest to its significance, lamenting how easily students memorize un-ending rap songs despite their needing a truckload of teaching tricks to remember directions for a simple assignment. Considering its importance, surprisingly little advice about how to motivate students is available on the Internet. The most helpful site reviews motivational research. In it Barbara McCombs states that "almost everything [teachers] do in the classroom has a motivational influence on students--either positive or negative. This includes the way information is presented, the kinds of activities teachers’ use, the ways teachers interact with students, the amount of choice and control given to students, and opportunities for students to work alone or in groups. Students react to who teachers are, what they do, and how comfortable they feel in the classroom." Based on research findings, we now know that motivation depends on the extent to which teachers are able to satisfy students' needs: • to feel in control of their learning • to feel competent • to feel connected with others How to Give Students More Control Being in control of their learning, means students have significant input into the selection of learning goals and activities and of classroom policies and procedures. Knowing that students need to have significant input into decisions about their learning situation does not, however, simplify the task of meshing what, when, how, and where students want to learn with mandated content and objectives, the school's schedule, and the teacher's room assignment. Fortunately, research suggests that students feel some ownership of a decision if they agree with it, so getting students to accept the reasons some aspects of a course are not negotiable is probably a worthwhile endeavour. Then, whenever possible, students should be allowed to determine class rules and procedures, set learning goals, select learning activities and assignments, and decide whether to work in groups or independently. In addition, while inconsistent with best practice in cooperative learning, allowing students to select learning partners has been shown to improve their motivation to learn. With this, as with other instructional issues, the teacher must continually weigh the benefits of making the "preferred" instructional decision against the motivational benefits of giving students choices among appropriate alternatives. How to Help Students Feel Competent Filling the need to be competent requires assignments that "cause students to challenge their beliefs, actions, and imagination by having them investigate and respond to issues relating to • survival, • quality of life, • problem solving, and/or • real products." The more interesting and personally relevant lessons are, the more motivating they will be. School-to- work programs have been particularly successful in this area; however, the relevance of class work to future employment, quality of life, and/or life skills should be shown in traditional classes as well. If we 16

- 17. have difficulty finding convincing examples of how class work has relevance to our students' lives, perhaps we should consider revamping our programs. To foster competence, "learning experiences should involve "both creative and critical thinking”...requiring students to: • define the task, • set goals, • establish criteria, • research and gather information, • activate prior knowledge, • generate additional ideas and questions, • organize, • analyze and • integrate all this information (Farges, l993) Use question starters promoting critical thinking and directions for writing lesson plans that facilitate critical thinking. How to Help Students Feel Connected The third factor, the need to feel connected, has been successfully addressed in advisory programs, cooperative learning, and, on a smaller scale, peer mentoring, peer counselling, and community service. Whether or not students participate in these programs, they need a "climate or culture of trust, respect, caring, concern, and a sense of community with others." (Deci & Ryan, 1991) Since student/teacher interactions play such a crucial role that even a single event can determine how the student feels about a class and how he will perform (Caruthers) you may want to review some of the following suggestions for creating a warm and nurturing climate: • Greet students at the door using their first name. Make eye contact and smile. • Listen to students and show you are listening using active listening techniques. Avoid giving advice. • Be genuine, be clear in approval and disapproval, and let students know you don't carry a grudge. Avoid sarcasm. • Talk to students about their discipline problems privately, perhaps outside the classroom door so as not to embarrass them in front of peers. • While using cooperative learning, walk around the room giving students an occasional pat on the back. Catch their eyes and give an okay sign. • Take pictures of all students putting them on the bulletin board. You may want to protect them by putting them under Plexiglas. • Celebrate birthdays and accomplishments during a scheduled "cultural event." One per quarter is probably sufficient. Put birthdays on a database so you can wish students a happy birthday on their special day. • Occasionally bring in goodies, such as hard candy, to distribute to the whole class while complimenting them on their progress. Be sure it is genuinely deserved and use positive remarks such as, "You've been really working at this," and "You've been thinking and making progress." • Have class officers in each class such as a secretary to record assignments for absentees and a cultural experience chairman or social chairman to plan events. Let students decide the duration of the jobs and whether they will be filled by appointment or vote. Volunteer service hours can be given if officers spend a lot of time on the class job. Remember the keys to motivating students are control, competence and connection. 17

- 18. Liz Regan's 20 Teaching Tips These teaching tips by Liz Regan found on the About.com website will be of general help to new teachers or others who simply wish to brush up on their techniques. 1) Pair work / Group work 10) Monitoring 2) Reading Aloud 11) Error Correction 3) Checking Understanding 12) Eliciting 4) Pronunciation 13) Checking Together 5) Speaking to Other Students 14) Reading before Writing in English 15) Brainstorming 6) Guessing Answers 16) Personalizing 7) Stopping an Activity 17) Translating 8) Feedback 18) Pacing 9) Dealing with Vocabulary 19) Concept Checking Queries 20) Using Dictionaries Teaching Tip 1: Pair work / Group work How: 1. Make a list of pairs of names before the lesson starts or while the students are coming in, or just tell them when the time comes: "Gianni, you work with Paola; Chiara, you’re with Stefano this time." 2. If there is an odd number of students make a group of three but break them up later in the lesson and put them into pairs with someone else so they get more chance to speak. 3. You could put them in small groups to start with if the activity allows. You could even make the activity a competition in small teams if the activity allows, seeing which team gets the most answers right. Use the board or a piece of paper for keeping score. 4. Change the partners quite often so that the students don’t get bored with their partner. This is especially important if there is a student who isn’t very popular with the others. Why: It’s good for the students to speak to each other in English (see TT5 for further explanation). It’s good for the students to work with another student sometimes rather than alone (see TT5 and TT13) for further explanation). Extra Info: I don’t put my students into groups bigger than 3 because I don’t think they get enough chance to speak in such a large group so they switch off, start fidgeting, get frustrated, let the hard-working students do all the work, fall asleep etc. In a pair, one student is speaking and one is listening and formulating a response, in a group of three, one is speaking, and usually 18

- 19. the other two are listening and formulating responses, in a group of four (or more), one is speaking, one or two are listening and formulating responses and the other one is asleep, aware that s/he hasn’t got much chance of getting a word in edge-ways. Or of course, in a group of four, two speak to each other while the other two often either fall asleep or end up speaking to each other too, in which case you might as well have put them in pairs in the first place. If you have an odd number of students don’t pair the extra student up with yourself - make a group of three somewhere. I used to take on the "odd" student myself when I started in EFL but I found that it didn’t work. The other students weren’t daft - they realised they were missing out on the teacher’s attention and I realised they were right - I was short-changing them by not monitoring them as I should. If you’ve got some talkative and some quiet students, pair the quiet ones together for the fluency activities (as opposed to the vocabulary/grammar activities) to encourage them to talk more. I used to put one talkative student in a pair with a quiet one, thinking that the quiet one would speak more if his/her partner was the chatty type. I was wrong - the talkative one monopolises the conversation and the quiet one is happy to let this happen. NB: If you only have one student, simply "pair up" with your student. Teaching Tip 2: Reading Aloud How: 1. Pick a student and ask him/her to read the instructions for Activity 1/2/3 or whatever. "Marco, please read the instructions for Activity 2 for us". 2. Pick a different student each time. Why: 1. It saves you doing it. 2. You can check pronunciation. 3. The other students may well understand the instructions better when read by another student. 4. The students are more likely to listen to another student than to you. 5. If they all read the instructions silently they will all finish at different times. If they listen to someone reading the instructions out loud they all finish at the same time. Extra Info: Getting students to read aloud used to be unpopular because the powers that be said that it was unrealistic as we never do it in real life - you read books silently, don’t you? Things have changed since then as it has since been argued that we indeed do it, e.g. "hey, listen to this; it says in the paper here that Prince Charles is already, secretly, married to Camilla! Listen - 'Prince Charles allegedly married Camilla Parker Bowles in a secret ceremony at Windsor Castle yesterday. The ceremony was attended only by the prince’s closest family and friends. A palace spokesman denied the rumour, saying that...'" 19

- 20. Teaching Tip 3: Checking Understanding How: 1. Ask your students "Is that clear?” 2. If it’s clear, fine. If anyone says "No, can you explain that? /Can you explain again?” don’t. Ask if one of the other students can explain it. 3. If nobody understands it, go through an example step by step together. They should get it then. 4. If they still don’t get it, go through another example together. 5. If the poor things are still lost either... o do the whole activity together as a class, if possible, or... o give up and go to the next activity. o If it’s a word they are having difficulty understanding, you could set it for homework and get the students to explain the meaning to you next lesson. 6. Another way to check understanding of instructions is to ask the students to imagine that you are a new student who has just come in - can they explain how to do the activity? 7. Another way to check understanding, not only of instructions, is by concept checking (see TT19). Why: 1. You need to check that the students have understood because they are unlikely to tell you if they haven’t - they will simply bumble through the exercise, doing it wrong, probably aware that they are doing it wrong, and losing confidence. 2. You need to ask "Is that clear?" rather than "Do you understand?" because the chances of a student saying "No, I don’t understand" are very slim - they will feel very stupid. Would you admit to not understanding something in front of others in a classroom situation? I wouldn’t! 3. The student who doesn’t understand will be convinced s/he is the only one who doesn’t get it and will not want to admit that in public. Questions like "Is that clear?" shift the blame to the quality of the instructions instead. Neutral ground - much nicer. Teaching Tip 4: Pronunciation How: 1. Model the word yourself. (This means you say it in a normal way to the students). Then get the students to repeat it after you, all together like in a chorus until they get it nearly right. Don’t worry if they aren’t perfect. Who is? 2. Then model the word again and ask individual students to repeat the word after you. 3. You could put the word on the board and ask the students how many syllables it has and then practise some stress placement. Ask them which the stressed (strong) syllable is. For example: before = 2 syllables be FORE = The second syllable is stressed. after = 2 syllables AF ter = The first syllable is stressed. computer = 3 syllables com PU ter = The second syllable is stressed. 20

- 21. afternoon = 3 syllables af ter NOON = The third syllable is stressed. If you know the phonetic alphabet you could write the words in that too. Why: 1. It helps the students to improve their pronunciation which is very important because there’s very little point in students learning a new word, learning what it means and how to use it in a sentence, if no one understands them when they say it because their pronunciation is so bad. 2. Doing a little pronunciation work can fill time here and there in a lesson. It’s especially useful as a filler (a quickie activity to fill those few minutes at the end of a lesson when you’ve run out of material but it’s a little too early to let the students go). Extra Info: If you’re planning to do some syllable work or stress placement or use the phonetic alphabet it’s a good idea to write the words, syllables, stress and phonetic spelling down before the lesson because, I don’t know about you, but I find it hard to do it spontaneously during the lesson! For some reason I get muddled and write the stress on the wrong syllable etc. If you want to do some stress placement work but you don’t know which syllable is stressed, look in a dictionary, especially one for students - it will have the stress indicated, usually by an apostrophe thingy. The syllable after the apostrophe thingy is the stressed one, usually. For example: be'fore 'after com'puter after'noon If you look in the first few pages of the dictionary it will explain how it indicates stress placement. Not all dictionaries indicate it in the same way. (For more information about dictionaries in general see TT20). Teaching Tip 5: Speaking to Other Students in English How: 1. Put the students into pairs or small groups (See TT1 for further explanation). Why: 1. Making students speak to each other instead of the teacher maximises STT (Student Talking Time) and minimises TTT (Teacher Talking Time). This is a good thing because the students are the ones who need to practise their English - you, hopefully, don't! 2. A lot of students will be using their English to speak to non-mother tongue speakers anyway so they might as well start getting used to it. For example, my students are Italian and they often need English to speak to other European clients and colleagues. Some of them never use English to speak to mother-tongue English speakers at all! Extra Info: Students like talking to the teacher because it makes them feel important and that they are getting value for money. While this is fine in a one-to-one lesson it is no good in a group because while one student is monopolising the teacher/conversation everyone else is losing out. 21

- 22. When I encounter students who want to talk to me all the time in a lesson (flattering though it is) I advise them (politely) to consider having individual lessons if they want the teacher's full attention all the time. If that doesn't work I explain like this: 60 minutes divided by 6 students = 10 minutes each; so they can each talk to me for 10 minutes and I will listen to each of them for 10 minutes which is sad really when they've paid for a 60 minute lesson. And, let's face it, it wouldn't really be 10 minutes because you have to take time off for taking the register at the beginning of the lesson, giving everyone time to hang their coats up, sit down, get settled, receive their worksheets, read the instructions, listen to the teacher presenting grammar points or whatever, do a listening exercise or a role-play, go through homework together, receive more homework, get ready to leave etc. 5 minutes would be more realistic. So there you have it, pay for 60 minutes and get 5. Where's the logic? If that doesn't work I do this: Let the student have his/her way. Yup! Smile and listen very attentively. Make sure that everyone else is listening too. Let him/her start rambling, taking up everyone's valuable time and then just pick him/her up on every grammar mistake and correct his/her pronunciation every second word. I find that the student in question usually enjoys this to start with; getting so much attention - having a one-to-one lesson in front of everybody - but the novelty soon wears off. I either correct the student aloud, frequently, or write his/her errors up on the board as s/he goes along ("don't mind me, do keep going, we can all learn so much from your mistakes"). Generally speaking, correcting a student every few seconds destroys the impact of whatever s/he was saying and makes them (and everyone else) lose the thread. Writing their mistakes up publicly on the board tends to make students shrivel up and die (See TT11 for an explanation about how to do error correction nicely). After this, in my experience, the student is generally quite happy to get on with pair work. And so are all the other students! Sometimes I have students who don't want to speak much until they can be sure of getting it right and not making mistakes because mistakes are bad things, right? (Wrong! See TT11 for further explanation). These students tell me that they want me to talk to them (individually) because they will learn correct English through listening to me (By osmosis, presumably!). They can't see the benefit of talking to each other because if they make a mistake the other student won't be able to correct them. (Actually, the other student often can correct them, and does correct them and that's what they don't like!). In such cases I explain like this: Learning English is like learning to play the piano/to drive/to swim etc. When you want to learn to play the piano/drive/swim is it enough just sit and watch other people doing it or do you need to have a go yourself and make mistakes and practise a lot until you get it right? Speaking together gives you that chance to have a go yourself and the time to practice. Or like this: If you honestly think that you will learn correct English by listening to a mother-tongue speaker speaking correct English, why don't you just rent an English video? It's a lot cheaper than paying lesson prices to listen to me. Teaching Tip 6: Guessing Answers How: 1. When there is a list of possible answers, encourage students to guess the answers (by saying things like "There are two words to choose from and only one gap to fill so you've got a 50% chance of being right!) 2. Encourage students to look at the words before and the words after the gap (in a gap- fill - a.k.a. cloze - exercise) to help them decide what type of word is needed in the gap. Will the answer be a verb? an adjective? a noun? In most exercises this will limit their choice of answers and therefore increase their chances of guessing the right one (see the previous point I made). 22

- 23. 3. If they are still looking a bit blank it's probably because they are suffering from "gap-fill tunnel vision" which means that this is what they see: Irrelevant gobbledegook an __________ with I needn't read this because it comes after the gap. Would you know what to write in the space? I wouldn't! 4. Encourage them to try to guess the meaning from the context (i.e. the sentence or paragraph the gap is in). Let’s look at the same example again, this time with the context: It rained yesterday when I was out but I hadn't got an __________ with me so I got wet. In this example the context tells us that the missing word is probably going to be "umbrella". 5. This technique also works well when there is a word which the students don't know in a sentence. If they have never seen the word "umbrella" before and it is in the sentence then the sentence will look something like this to the student: Irrelevant gobbledegook an umbskjdhfskjflla with I needn't read this because it comes after the gap. Some students will panic at this point and ask you what an umbskjdhfskjflla is. You don't need to spoon-feed them the answer. If the students use the context to help them they will probably be able to work out the meaning. (See point 4 above) and thus gain confidence as learners. Why: 1. The students know a lot more than they think they know - the posh term for this is "passive knowledge". This basically means that somewhere in the past they have seen or heard this word or phrase but they don't remember it consciously. (They don't know they know - they think they don't know, but you know better, you think they know - confused yet?) Anyway, if you can get them to make a guess, the chances are that they will get it right quite a lot of the time. If you put the students into pairs or small groups the chances are that with their combined passive knowledge they'll get most of the answers right, though they won't know how they did it. They'll probably think it is just luck. It isn't. Of course, the upshot of all this is that they get most of it right and consequently they feel very good. Their confidence is raised and that is half the battle with speaking a foreign language. 2. In real life (outside the classroom) the students will be put in situations where they don't know all the answers or they don't know all the words etc. If they have developed the confidence to trust themselves to make an educated guess here and there it'll help them survive linguistically. 3. In many English language exams it is necessary to do gap-fill/cloze exercises. Students who leave spaces because they don't know the answer should, in my humble opinion, be deemed "too stupid to live" and dealt with accordingly. Students taking exam courses should be encouraged to make guesses left, right and centre in order to avoid ever leaving a space on an exam paper. If nothing is written in the gap the student will receive no marks. If something is written in the space there is a chance, a fair chance, that the answer will be right. Teaching Tip 7: Stopping an Activity How: 1. If you have a small enough group that you can be heard by everyone, just say something like "OK, you can stop there. Well done everyone. Thank you, you can 23

- 24. stop now. Yes, that includes you, Giovanni!" Then give the students a few seconds to finish their sentences until the room falls quiet. Let them finish what they were saying. 2. If you have a big group so you won't be heard if you try talk over everyone then don't bother to shout yourself hoarse, simply have a certain place in the classroom where you go and stand when you want everyone's attention and go and stand in it. The students will stop talking very soon. (I stand in front of the board, facing the class which gets their attention because for the previous ten minutes or so I've been cruising round the room monitoring). You can explain to students at the beginning of the course, "When I want your attention I will stand here and you will stop what you are doing and listen to me because I don't like shouting for your attention. Is that clear"? When: 1. It's not important if the students have finished the activity - it's the taking part that counts, as they say. 2. It's a good idea to stop things while they are swinging because it means you never hit the students' boredom threshold. Leave them wanting more and enthusiasm will remain high. On the other hand, don't stop it too soon because not everyone will have had a chance to speak or guess the answers yet so they'll feel cheated. Teaching Tip 8: Feedback How: 1. Ask one of the students what the answer to question 1 is. If s/he gets it right, fine. If not, ask if anyone else knows the answer. (If nobody knows and nobody can guess, you'll need to give it to them). 2. Ask one of the students what the answer to question 2 is. If s/he gets it right, fine. If not, ask if anyone else knows the answer. (If nobody knows and nobody can guess, you'll need to give it to them). 3. Ask one of the students what the answer to question 3 is. (Are you getting the hang of this?) 4. In the "True or False?" activities on my worksheets, the feedback questions would be: "How many of your guesses were right? How well do you know your partner? Which of your partner's answers surprised you?" Why: 1. Getting feedback from the students (i.e. information about what they've just done) means you can check how they coped with the exercise. You don't only need to get the answers. You can find out if they liked that type of exercise or not - if not, can they suggest ways to improve it? 2. You can check their pronunciation. You can deal with queries. You can allow the feedback session to develop into a class discussion, if you like. Whatever. Extra info: You can initiate a feedback session about the lesson as a whole as a filler (five-minute activity) to fill the last few minutes of a lesson by asking the students to decide which of this lesson's activities was the most enjoyable/useful and why, then compare their choices with 24

- 25. their partner's or have an open-class discussion about it where the whole group talks to you and airs their views. Teaching Tip 9: Dealing with Vocabulary Queries How to avoid doing it: 1. Get the students to read the exercise completely before starting to actually do anything. They can underline the words they don't know, or (more positively) underline the words they do know. 2. When a student asks you to explain the meaning of a word, don't. Ask the other students if anyone can explain it. 2. You could put the students in pairs or small groups and get them to explain the words they don't know to each other. This sounds daft but it's quite logical really - the words Gianni is having difficulty with won't necessarily be the same ones that Marco is struggling with. (Beware of the students' tendency to translate the words. See TT17 for info on Translating). 3. It's a good idea to get the students to try to guess the meaning of the word from the context it's in. (See TT6 for further information on "deducing meaning from context"). 4. Get the students to look the word up in a (preferably English to English a.k.a. monolingual) dictionary, should such a thing be available (see TT20 for further information about dictionaries). Why to avoid doing it: 1. You are not a dictionary. You don't even look like one, do you? 2. There's a world of difference between telling someone something (spoon-feeding students who soon get into the habit of switching off, being passive, letting the teacher do all the work for them and not bothering to try to remember a single thing) and teaching someone something (creating an environment and a set of circumstances in which someone can actively learn, practise new skills, and develop confidence in his/her own abilities). 3. One day, out there in the big wide world, the students will be faced with situations in which they will not know all the words and you won't be there to help them. Then what will they do? (With any luck they will be able to fall back on all the useful skills you've taught them in class.) Explaining new vocabulary As a last resort, give the students an explanation of the new word or phrase in English. It's a good idea to give them an example sentence or two containing the word or phrase so that they can see how to use it. You may find it useful to demonstrate or mime the word to convey it's meaning quickly. Or maybe a quick line-drawing (of the "stick-man" type) would convey the meaning more quickly? Sometimes a synonym (similar word) is useful (e.g. wealthy = rich) or an opposite (e.g. wealthy = the opposite of poor). Extra info: If a student still thinks I should explain all the new words to him I refuse and explain like this: If you give a starving man a fish, you feed him for a day. If you teach him how to fish he can feed himself for life. (I explain "starving" as "very, very, very hungry"). In this case the "fish" is the explanation of a word, given by you. The "how to fish" is the ability to guess words from context, the confidence to ask a peer (a classmate, a colleague etc.) if they know the meaning, and the ability to use a dictionary. 25

- 26. Teaching Tip 10: Monitoring How: 1. While the students are doing an activity you walk slowly round the classroom and listen to their conversations. 2. You can sit down too, if there are enough chairs, but try to sit in the background a bit or the students will direct their conversation to you. 3. Look at one pair whilst actually listening to a different pair nearby. Correct the pair nearby (which will probably make them jump because they thought you were listening to the pair you were looking at) just to keep everyone on their toes - they never know when you're listening to them so they can't ever switch off or revert to their mother- tongue. 4. Be ready to massage any flagging conversations back into life, to stop students monopolising conversations, to stop students falling out with each other and to offer encouragement and praise where appropriate. Listen and supervise. 5. Take a piece of paper and a pen with you on your travels round the classroom so that you can jot down any howlers (which can then be dealt with at the end - see TT11 for further explanation). Why: 1. If you spend your life in the classroom sitting down, this is your chance to stop numb- bum syndrome - get up and wander round. If you spend your life in the classroom on your feet, this is your chance to put your feet up (not literally, maybe, though I did when I was pregnant!) - sit down to listen to the students. 2. Monitoring gives you the opportunity to hear how the students are coping with the activity and to make notes about pronunciation, vocabulary and grammar points that are causing difficulty. I see the role as one of listener/supervisor/facilitator/encourager - not as one of error corrector. Extra Info: Although it's a good idea to indicate that you're actually listening to the students (even to the point of feigning interest in what they are saying) I wouldn't suggest crouching down to table height in order to listen to the students - it looks silly. Apparently, (according to books on body language) tipping your head to one side gives the impression that you are listening avidly to someone so if you were thinking of switching off and not listening to your students at all (...me??...never!!), tip your head to one side first and they'll be none the wiser! I generally don't correct mistakes very much when I'm monitoring - I jot them down and do a bit of error correction later because if I get caught up correcting one student's mistakes during the activity I can't monitor the other students properly and by the time I get back to monitoring I find that everyone has reverted happily to their mother tongue. 26