3 Managing Motivation to Learn - Course Resource Book

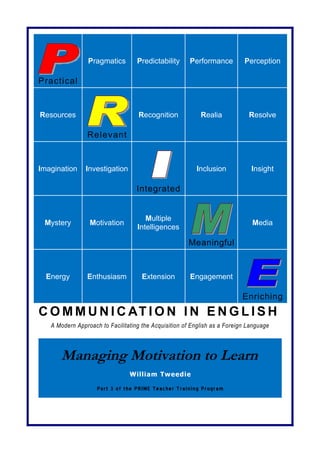

- 1. Pragmatics Predictability Performance Perception Practical Resources Recognition Realia Resolve Relevant Imagination Investigation Inclusion Insight Integrated Multiple Mystery Motivation Media Intelligences Meaningful Energy Enthusiasm Extension Engagement Enriching C O M M U N I C AT I O N I N E N G L I S H A Modern Approach to Facilitating the Acquisition of English as a Foreign Language Managing Motivation to Learn William Tweedie Part 3 of the PRIME Teacher Training Program

- 2. Managing Motivation to Learn Course Resource Book William Tweedie © 2005 - 2010 Kenmac Educan International & William M Tweedie TABLE OF CONTENTS 2

- 3. MANAGING MOTIVATION TO LEARN.............................................................................................................2 COURSE RESOURCE BOOK.............................................................................................................................2 WILLIAM TWEEDIE........................................................................................................................................2 REVISED AND EXPANDED COURSE OUTLINE..................................................................................................4 GOALS AND OBJECTIVES................................................................................................................................4 INTRODUCTION............................................................................................................................................6 STUDENT MOTIVATION AS CRITICAL TO LEARNING SUCCESS ........................................................................7 MOTIVATION, ATTENTION AND LISTENING, SETTING AND ACHIEVING PERSONAL GOALS..............................9 TEACHING (THE CATALYST FOR LEARNING), CONTROL, HEALTH, EVALUATIONS...........................................24 TOP 6 KEYS TO BEING A SUCCESSFUL TEACHER............................................................................................41 A PRIMER ON BEHAVIOR MANAGEMENT (ROAMING THE CYBER-HALLWAYS WITH A FORGED PASS)..........................................................................42 FOR NEW TEACHERS: WELCOME TO THE PROFESSION! ...............................................................................47 BEHAVIOR MANAGEMENT CHECKLIST.........................................................................................................51 TIPS FOR BECOMING AN EFFECTIVE AND WELL-LIKED BEHAVIOR MANAGER ...............................................54 GIVING AND GETTING RESPECT ...................................................................................................................................................................63 MANAGING BEHAVIOR VIA TEACHING STYLE ..............................................................................................73 COMPETITIVE VS. COOPERATIVE LEARNING FORMATS................................................................................77 WHEN MISBEHAVIOR OCCURS IN GROUPS .................................................................................................81 CLASSROOM MANAGEMENT.......................................................................................................................83 THE USE OF PERSONAL CHOICE IN CLASSROOMS.........................................................................................87 HOW TO DEAL WITH DISRUPTIVE STUDENTS...............................................................................................88 TEACHING IDEAS THAT WORKED: BEHAVIOR MANAGEMENT ......................................................................90 THE TOP 5 LIST............................................................................................................................................99 ON THE WEB: CLASSROOM MANAGEMENT...............................................................................................102 REMEMBERING YOUR GOAL: THE ART OF COMPROMISE .................................................................104 POSITIVE DISCIPLINE.................................................................................................................................109 ANSWER KEY FOR 10 LEVELS OF REINFORCEMENT ACTIVITY......................................................................115 THE ART AND CRAFT OF MOTIVATING STUDENTS......................................................................................117 QUOTATIONS ABOUT MOTIVATION ..........................................................................................................119 Articles are the property of the authors and copyright owners. Permission is granted for reproduction. Please cite the authors and source. 3

- 4. Revised and Expanded Course Outline I. PRIME Task 1. a. Relationship between Multiple Intelligences (MI) and Motivation i. How do we learn? ii. Gardener’s MI Theory - Whole Group Activity iii. MI ↔ Motivation - practical application – Your story II. Setting the Stage a. Goals and Objectives i. Personal and Group Goals ii. PG / CG Objectives III. Process Framework a. Expectations b. Routines c. Structure i. Part 1 ii. Part 2. iii. Evaluation / Feedback d. Consequences IV. Managing Motivation a. Global Challenge b. Sample Lesson c. Overview i. What is it? ii. What are the needs that drive Motivation? iii. Reasons for importance, it’s absence, and behaviors associated with high academic achievement iv. Seven Strands/levels of Engagement V. Attention Training a. Need b. Activities – Simple/Individual → Complex/Group Lunch Break – Classroom Management Profile (CMP) task VI. PRIME Task 2 – Review and CMP VII. Goals and Objectives task – Small Group Activity VIII. Behavior Management Tips – Small Group Activity IX. Behavior Management Checklist (BMC) a. Checklist of General Strategies – individual Activity b. Personal Management Plan – Small Group Activity Goals and Objectives Facilitator’s Personal Goal (PG) To deepen my understanding of the concept of Motivation and the dominant factors in the challenge of managing it. Facilitator’s Course Goal (CG) To create the awareness of some elements, styles, strategies, and techniques in Managing Motivation (MM) that will help SCT facilitators of learning positively affect their students’ motivation to learn 4

- 5. Facilitator’s Objectives Facilitator’s PG – 1. to provide opportunities for facilitators of learning to share their knowledge and experience with Motivation challenges 2. to learn new strategies that have been used successfully in this SCT context Facilitator’s GG – 1. to present current research and evidence of practice on the topic of Motivation 2. to provide opportunities for facilitators of learning to develop and practice new styles, strategies and techniques in Managing Motivation 3. to provide opportunities for facilitators of learning to begin developing personal and professional MM plans 4. to establish mechanisms to continue to assist facilitators of learning with Motivation issues My Personal Goals and Objectives __________________________________________________________________________________________ __________________________________________________________________________________________ __________________________________________________________________________________________ __________________________________________________________________________________________ __________________________________________________________________________________________ __________________________________________________________________________________________ __________________________________________________________________________________________ __________________________________________________________________________________________ __________________________________________________________________________________________ __________________________________________________________________________________________ __________________________________________________________________________________________ __________________________________________________________________________________________ __________________________________________________________________________________________ __________________________________________________________________________________________ __________________________________________________________________________________________ 5

- 6. Introduction This book is the product of fifteen years of combined research and practice in the field of classroom management, as it is traditionally defined (behaviour management is a better representation and the title of this book, Managing Motivation even better, in my opinion, for professional facilitators of learning*1). It presents some of the best approaches and ideas regarding the myriad array of factors that make up this complex topic including cognitive, metacognative, social, and psychological. It is complex. However, facilitating learning effectively is not to be taken lightly and understanding human behaviour is at its core. It is most likely the most important area that a good facilitator must continually undertake in which to broaden and deepen understanding. If one begins with the notion that teachers do not manage classrooms, that they manage people, then one is taken beyond the physical boundaries of rooms to the limitless possibilities in the human mind and spirit. There, one can begin to understand and affect behaviour, guiding it in such a way that ideally is demonstrated in a complete engagement in the most important human activity – learning… for each student. I hope these resources and this course provide you with some insight and help you to help your students become more excited about being in your classroom or wherever you are helping them become better learners. Have fun! William M Tweedie 1 Personally, I would like to have the label “Teacher” eliminated from the English lexicon. 6

- 7. Student Motivation as Critical to Learning Success http://www.oecd.org/document/51/0,2340,en_2649_37465_15481523_1_1_1_37465,00.html Successful learning depends on good instruction and the ability to store knowledge, but also on how students approach the process of learning, according to a new OECD report (30/09/2003) drawing on a study of 15-year-olds in 26 countries. Learners for Life - Student Approaches to Learning provides evidence that students with strong motivation and a belief in their own abilities are able to take better control of their own learning, and that this helps them to perform much better at school. These findings suggest that education systems need to concentrate not just on providing sound instruction but on helping students develop attitudes and habits that allow them to manage their own learning effectively, both at school and beyond. The findings cover Austria, Australia, Belgium (Flemish Community), Czech Republic, Denmark, Finland, Germany, Hungary, Iceland, Ireland, Italy, Korea, Luxembourg, New Zealand, Norway, Portugal, Scotland, Sweden, Switzerland and the U.S. The report draws on data gathered under the year 2000 round of the Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA), which assessed the knowledge and skills of 15-year-olds in 43 countries. Within PISA, students were asked about four aspects of their approaches to learning: motivation, self-related beliefs (i.e. self-confidence), learning strategies, and whether they prefer co- operative or competitive learning situations. The report groups students into four clusters, according the learning approaches that they say they use. The strongest learners can be characterised by effective learning behaviour as well as habits and beliefs that foster learning. Students in this cluster are especially likely to use strategies employing comprehension: "evaluation" and "control" strategies. They are also likely to have especially high confidence in their ability to achieve even difficult goals (self-efficacy), to put in a large amount of effort and persistence and to be interested in reading. In Finland, Norway and the United States, 28% of students fall into the cluster of strong learners, while in the Flemish Community of Belgium and in Switzerland only 23% of students make this category (see Figure 1). Students rated as the strongest learners in terms of these characteristics perform, on average across countries, 63 score points or nearly one proficiency level on the PISA scale higher than students in the "weakest learners" category. The report shows not just that students who are well motivated, for example by an interest in reading, are more likely to reach higher levels of literacy, but also that self-confident students do better, and in particular that students who report applying effective learning strategies tend to take better control of their own learning. Such students think more actively about what they need to learn and monitor their own progress, rather than relying on teachers every step of the way. In addition to achieving better results at school, they are better equipped to become lifelong learners, i.e. to continue learning beyond the close supervision of the classroom. The report shows striking similarities in the relationship between various learning approaches and student performances across OECD countries, despite different cultures and education systems. Schools in most countries have at least some pupils who lack confidence, are poorly motivated, and have weak learning strategies, indicating that the main task is for individual schools to address these issues among their weakest students. The report also shows that, across countries, students tend to show higher confidence in reading than in maths. Despite these similarities, however, there are also differences across countries. Danish students have the highest level of confidence in both their reading and their mathematical abilities, while Korean students have the lowest level of confidence (see Figure 2). 7

- 8. The report also notes differences in the approaches to learning among different groups of students: • Although boys perform less well than girls in reading literacy, they have some overall advantages as learners. For example, they are more confident than girls of succeeding in learning tasks, even where they find them difficult. On the other hand, girls think more of their reading abilities, and have a greater interest in reading. • Students from more advantaged social groups are also stronger as learners, and in particular have much greater confidence in their ability to succeed. • Immigrant students, despite performing significantly less well in reading than native students in most countries, do not have generally weaker approaches to learning. In most countries their approaches are similar, and in Australia and New Zealand, immigrant students display stronger motivation, self-confidence and learning strategies than students born in those countries. Overall, the report's findings suggest that there are big educational gains to be made from strengthening student approaches to learning. About a fifth of all differences in student literacy performance are associated with variations in such approaches. Educational reforms may need to reorient education systems to ensure that teachers consciously point students towards effective learning strategies, and help them to build the confidence and interest needed for them to adopt such strategies. This may require teacher training to be changed to ensure that teachers understand how to foster positive learning approaches among their students as well as how to impart knowledge. 8

- 9. Motivation, Attention and Listening, Setting and Achieving Personal Goals http://www.muskingum.edu/~cal/database/general/motivation.html Motivation is an inner state of need or desire that activates an individual to do something that will satisfy that need or desire. Because motivations derive from needs or desires internal to the individual, others cannot "motivate" an individual but must manipulate environmental variables that may result in an increase or decrease of motivation. Motivators exist on a continuum from intrinsic to extrinsic, describing the relationship of the goal to the activity necessary to secure it. Intrinsic motivators are goal and activity related; while extrinsic have little relationship to the goal or task. Both types of motivators can be effective. Intrinsic motivators have the advantage of constancy; in other words, once an individual identifies the activity necessary to achieve the goal, it remains constant. Extrinsic motivators, on the other hand, involve prior assessment of the environment each time in order to determine the activity needed to achieve the desired end. But if an individual is unable to identify the necessary "trigger" activity, extrinsic motivators are the logical first-step. Purpose of Motivation Strategies The primary purpose of motivation strategies is to develop or to trigger an inner desire for beginning or completing an activity. Advantages of Motivation Strategies One advantage of motivation strategies is their applicability. They may be applied in a variety of contexts including school, work, and personal affairs. In addition, they may be used for any subject or task. Another advantage is their flexibility. Motivation strategies may be modified to meet the needs of a particular individual, subject, or task. They may be used in combination to form an effective motivational program. Specific Motivation Strategies Some motivation strategies are intended for use by students, others are relevant to instructors, and some may be applied by both students and instructors. Students may benefit from the sense of control, health concerns, self-talk, support systems, personal goal chart, and motivation and class attendance strategies. 9

- 10. Instructors might incorporate the student needs, relevance, make learning active, make teaching the catalyst for learning, level of task difficulty, and knowledge of evaluation results strategies into their course work and activities. The anxiety and voice tone, creating interest, changing attitudes, and desire to learn strategies are appropriate for both students and instructors. It is important to remember that no one strategy is more powerful than others and that the strategies are interrelated. The effectiveness of the strategies varies by individual and situation. Though we tend to concentrate on those conditions to which we are most responsive, when one condition is out of our control, we should attempt to manipulate another condition. Student Needs This strategy, from Hoxmeier (1987), is based on Maslow's (1943) model of human needs. Maslow identified five needs and arranged them into a pyramid, with the lower levels representing the most powerful needs. At the lowermost level are physiological needs, or basic needs for food, water, sleep, and shelter. The next level of needs relates to security. The need to belong is the third level. Love and self-esteem occupy the fourth level of needs. The need for self-actualization is the uppermost level. The needs are prepotent; meaning the stronger needs at the bottom must be met before the weaker needs toward the top can be fulfilled. Needs may emerge and subside at various times. Obviously, basic physiological needs should not be used as motivators, but the needs for security, approval and self-esteem, and self-actualization can. The goal is to make learning responsive to these student needs. The following paragraphs explain how this may be accomplished. Need for Security The need for security includes the ability to satisfy basic physiological needs, safety, financial security, job security, and technological competence. Making learning responsive to student needs for security may be accomplished in two ways. Use of Fear • Fear is counterproductive. One should avoid the use of fear in attempting to motivate students because it undermines their need for security and it is often too ambiguous to be of help. Instead, one should identify the ways in which a student feels insecure and then attempt to foster the student's sense of security by providing him/her with concrete actions that will bring about that sense of security. • As an example, consider a student who is insecure about his/her work because of his/her memory abilities. Instead of telling him/her "You will fail this class unless you improve your memory," instruct the student in a variety of memory strategies that target the particular memory task at hand. Emphasize the Positive 10

- 11. • Students need to feel secure of their capabilities and performance. Design assignments that draw from and build on these strengths. Students are more motivated to do things they feel they have a chance of successfully completing. Need for Approval and Self-Esteem The need for approval and self-esteem involves the desire to be valued as a member of a group and as a human being. We seek recognition and admiration of our skills and abilities. Making learning responsive to student needs for approval and self-esteem may be accomplished in three ways. Praise • Instructors can motivate students by praising even small accomplishments. However, one should avoid insincere praise and judgmental comments. Use specific comments like "Your use of examples to illustrate the main points in your paper is great" rather than "Your paper is good." Students usually can see right though such trivializing praise. Structure • Instructors can provide students with the structure needed for success. First, provide simple and clear instructions for completing a task. Second, break down large assignments into smaller, more manageable tasks. Then develop a structured plan of action for completing each mini assignment. Avoid using tricks or gimmicks. As students gain proficiency, they can learn to impose structure themselves. Remind Students of Successes and Goals • Reminders about past successes or future goals can be powerful motivators. Instructors and students alike can keep track of academic and social successes in the form of a journal; record the date and nature of each success. Use a journal or poster to record short-term and long-term goals, and refer to the list often for inspiration. Try to link the task at hand with one or more of the goals, and emphasize how completing the task will lead toward fulfillment of a goal. See Setting Personal Goals below. Need for Self-Actualization Motivations may arise from an individual's need for self-actualization, or one's need to express creativity and live up to one's potential. There are two ways to make learning responsive to the student's need for self-actualization. Create Anticipation • Motivate students to learn by creating anticipation. This strategy is not unlike the movie industry's use of "trailers" for motivating people to see a movie or Paul Harvey's radio show that tells "the rest of the story." In the classroom, the instructor can preview a subject and encourage students to ask what will happen next or develop an explanation beforehand. Create a sense of suspense to motivate learning. Students can learn to create anticipation themselves by using past lectures and required readings to anticipate what will be covered next in a lecture. Creative Structure • Develop unique and creative methods of presenting important concepts. For example, reinact important war-battles or role-play critical events in history. Or, give students the opportunity to apply their knowledge in creative ways. Have them act as teachers or tour guides and present new information in creative ways. 11

- 12. Attention and Listening Background Information on Attention and Listening Attention is the ability to concentrate mentally and observe carefully. Listening refers to applying oneself to hearing something. One must pay attention in order to listen effectively, but attending is also important when doing other tasks like reading, writing, taking tests, and reviewing information. The quality and quantity of attention is vital to the learning process. The process of attending influences the ability of the student to move new information from sensory memory to short-term memory. One must maintain attention through rehearsal in order for information to be moved into short-term memory. Purposes of Attention and Listening Strategies The primary purpose of attention strategies is to provide a non-medication alternative to improving concentration and attending. The strategies for improving attending and listening may be applied in a number of academic situations, such as: • during lectures • while doing assigned readings • during individual study sessions • when completing homework assignments • during group study sessions • while taking tests Advantages of Attention and Listening Strategies Attention strategies are helpful in a number of respects. Academically, improved attending skills can positively impact a student's performance in note taking, class participation, reading, following directions, completion of assignments, group learning, exam preparation, and exam taking. Students with selective attention or ADD have an impaired learning process. Therefore, strategies designed to aid in attending are vital to their academic success. Socially, improved attending skills can positively affect a student's self-image and self-esteem as he/she begins to appreciate his/her strengths and weaknesses. This, in turn, may impact a student's willingness to participate in group activities, performance in group activities, sense of organization and control, and ability to behave appropriately in unstructured situations. Basic Health Needs Since the inability to pay attention may be caused or amplified by poor health, it is important that students attend to basic health needs. This strategy is a good "first-step" to addressing attention and listening difficulties because it is fairly straight-forward, it is probably one of the easiest strategies to implement, and it may address one of the fundamental causes of attention deficits. Health is an ongoing, continuous process. One cannot be concerned with good health one week but not the next. Therefore, it is important that good health habits become a part of each student's routine. The following facets of basic health needs should be discussed and evaluated with students. 12

- 13. Sleep • Is the student getting adequate rest and sleep? • Does the student have a sleep routine or is he sleeping erratically? Diet • Is the student eating two or three balanced meals a day? • Is the student overindulging in junk food, cigarettes, or drugs and alcohol? Physical Conditions • Has the student's hearing and vision been checked? • Has the student been evaluated for attention deficit disorder? • Has the student been screened for affective, neurological, or chromosomal disorders? • Does the student seek immediate medical attention for even minor illnesses? Fitness • Does the student exercise regularly? Mental Health • Does the student meet adversities calmly and rationally or stressfully and irrationally? • Does the student confront or avoid reality? • Does the student worry excessively? • How does the student handle stress? Self-Image A student who has difficulty paying attention and listening often performs poorly in school and social settings; this, in turn, may negatively impact his/her self-image. A student's image of him/herself can greatly affect the learning process. Find more information about self-image in the Eliminating Internal Distractions section. The following tips may be used by instructors, advisors, counselors, tutors, and parents to help a student improve his/her self-image. Numbers 7 through 14 are from Coleman (1993, p. 90-96). • Help the student identify his/her assets. • Encourage the student to constantly remind him/herself about those assets. • Heighten the student's awareness of his/her ambitions and goals, both long-term and short- term. • Help the student to develop a realistic plan of action for reaching his/her goals. • Encourage the student to constantly assess his/her progress toward goals, including why or why not the goals have been reached. • Congratulate and reward the student for completing tasks or reaching goals, and encourage the student to do so for him/herself as well. • Take notice of and praise good behavior, including learning behavior and social behavior; positive reinforcement is important for young learners as well as college students. • Use "descriptive" praise instead of judgmental comments; for example, one might comment that a student's research paper "makes good use of examples and statistical data" rather than "this is a great paper." • Avoid belittling or humiliating comments, and avoid comparing the student and his/her progress to other students. • Provide the student with clear and simple instructions about a task; use as many senses as possible. 13

- 14. • Practice social skills with the student. • Provide the student with social or academic situations in which he/she will be successful. • Limit the number of decisions the student has to make. • Discuss the student's problems in private. Monitoring of Learning Behaviors and Outcomes Self-Monitoring of Learning Behavior • Direct the student in evaluating his/her learning behaviors, offering feedback on the "correctness" of his/her evaluation. • The student will either become confident in his/her ability to evaluate himself/ herself, or the student will become aware of his/her incorrect assumptions. Self-Monitoring of Learning Outcomes • Direct the student in maintaining written records of how tasks were completed, grades for tasks, professor comments, grade point averages, etc. • Help the student learn to link inputs and outcomes for each task. • Efficient learners are always aware of their academic standing. Attention Training Activities Concentration You should direct students to reinforce only good concentration strategies. In other words, don't reinforce learning behaviors that represent poor concentration strategies. Students should also be aware of and analyze barriers to concentration and sources of distractions in their study areas. Poor Concentration Habits The following list describes poor concentration habits that students should become aware of and attempt to change in order to improve concentration. • Changing to a different learning activity because of an inability to concentrate on the task at hand. • Choosing study areas or seats in the classroom with known distractions. • Jumping into a task without understanding directions, considering the purpose of the task, or relating the task to the course as a whole. • Vigorously debating with the instructor in class or avoiding class participation altogether. • Doing other things, or thinking about doing other things, when one sits down to study. Conditions Necessary for Concentration The following list outlines conditions necessary for concentration. • Eliminate external and internal distractions. • Make sure you are healthy and rested. • Address organizational and time management needs. • Avoid daydreaming about things you want to do by scheduling time to actually do them. • Avoid anxiety about things you have to do by making a list of them to complete later. • Fully understand the purpose, instructions and expectations of the task at hand. 14

- 15. Memory and Yoder (1988) present a six-part guide to improving concentration. Each part corresponds to the goals of the strategy, and a specific course of action for addressing each of these goals is given. • Insure understanding. o Read or listen to instructions and directions carefully. o Know the expectations that must be met. o Seek clarification from the instructor if necessary. o Do not begin a task until all instructions and expectations are fully understood. • Maintain interest in the subject matter. o Develop an interest in the course by talking with other students who enjoyed the class or are majoring in that subject, by reading magazine articles, or by watching television programs related to the subject. o Develop an interest in the task by previewing the material to find points of interest to you, by focusing on main points rather than details, or by looking for general principles and broad generalizations. o Avoid daydreaming about things you would rather be doing by setting aside time in your schedule to do these things. o Arrange for variety in studying by working on one course or task for a short period of time or by varying the activities in each study session. • Have a purpose. o Relate the task to specific short-term or long-term goals. o Consider a target at which to aim, such as a completion date, a level of quality, a level of improvement, or a grade. • Maintain a pattern of attention. o Be aware of good and bad concentration habits. • Transform good procedures into habits. o Document the use of concentration strategies and the academic outcomes of using them. o Always work in your designated study area that is free of distractions. o Study at similar times every day to develop a routine. • Reward productivity. o Treat yourself to a reward when you practice good concentration habits. 60-Second Synopses Strategy Huffman's (1992-1993) 60-second synopses strategy is used in tandem with Memory and Yoder's (1988) guide to improving concentration. It is a group activity to introduce, reinforce, and apply the concentration-improving tips. The 60-second synopses strategy has several advantages. First, it is an active process that requires the use of a number of skills such as reading, writing, speaking, listening, application of information, analytical processing, and cooperation. Second, it is an interactive process, allowing students to interact with and learn from one another. Third, it is an efficient process, exposing students to a large amount of information in a short time. Finally, the strategy may be modified to meet students' needs. For example, tutors may work one-on-one with a student covering each of Memory and Yoder's (1988) strategies over several weeks. And, once concentration strategies have been presented and discussed, students may practice developing 60-second synopses for other material, both written and oral. The steps in the 60-second synopses strategy are as follows. • Divide the group into pairs or groups of three students. • Assign each group one of the six sections of Memory and Yoder's strategy for improving concentration. • Each group then reads and annotates its assigned section. What are the main points of the section? How do the suggestions relate to personal experience? 15

- 16. • Each group then organizes its information and develops a plan for presenting it to the rest of the class. There is a 60-second time limit for the presentation. • Each group makes its 60-second synopsis presentation. The group members may take turns or may select a spokesperson. Encourage presenters to use anecdotes and testimonials. • After each group presentation, the class evaluates the strategy and adds more examples and personal experiences related to the strategy. • When all group presentations are done and all strategies have been assessed, the floor is open for students to share additional strategies they have used to improve concentration. • The class then discusses in what situations certain strategies would be most or least effective. • Each student writes a journal entry relating the strategies to upcoming course assignments. • Students are encouraged to evaluate their level of concentration throughout the semester. Jigsaw II Group Activity The jigsaw strategy is used to develop the skills and expertise needed to participate effectively in group activities. It focuses on listening, speaking, cooperation, reflection, and problem-solving skills. • Listening - Students must listen actively in order to learn the required material and be able to teach it to others in their original groups. • Speaking - Students will be responsible for taking the knowledge gained from one group and repeating it to new listeners in their original groups. • Cooperation - All members of a group are responsible for the success of others in the group. • Reflective thinking - To successfully complete the activity in the original group, there must be reflective thinking at several levels about what was learned in the expert group. • Creative thinking - Groups must devise new ways of approaching, teaching and presenting material. Directions for the jigsaw strategy are given below. Define the group project on which the class will be working. • Randomly break the class into groups of 4-5 students each, depending on the size of the class, and assign a number (1 to 4-5) to students in each group. • Assign each student/number a topic in which he/she will become an expert. • The topics could be related facets of a general content theme. • For example, in a computer class the general theme might be hardware and the topics might be central processing unit (student #1), memory (student #2), input devices (student #3), and output devices (student #4). • Rearrange the students into expert groups based on their assigned numbers and topics. • Provide the experts with the materials and resources necessary to learn about their topics. • The experts should be given the opportunity to obtain knowledge through reading, research and discussion. • Reassemble the original groups. • Experts then teach what they have learned to the rest of the group. • Take turns until all experts have presented their new material. • Groups present results to the entire class, or they may participate in some assessment activity. Attention Training Attention training techniques differ from other attending strategies because they allegedly produce permanent increases in memory capacity (Herrmann, Raybeck and Gutman, 1993). Research with normal adults, however, indicates that the techniques are more effective for specific tasks rather than attention in general. Among brain-damaged patients, results are more encouraging but, again, it is likely that confidence and task-specific skills are affected rather than general attention capacity. Herrmann, Raybeck and Gutman (1993) describe several attention training techniques. 16

- 17. • One attention training method involves practicing listening for faint sounds or looking for dim lights. This method targets one's ability to sustain attention. • Another technique entails practicing doing two things at once in order to increase one's ability to divide attention. • A third method involves picking out details in visual images or sounds in music in order to hone one's ability to detect details. • Another technique involves practicing concentrating in distractive environments in order to increase one's ability to resist distractions. • An alternative to the attention training methods is simple practice; select a situation in which you want attention to improve and then place yourself in that situation repeatedly and practice paying attention. Setting and Achieving Personal Goals A goal is an objective or an end result of one's actions. A goal may be something one works toward or something one would like to improve upon (Michaels, et al., 1988). Short-term goals, such as passing a test or doing well in a contest, are sought over a relatively short period of time, while long-term goals, such as finishing college or succeeding in a certain career, take longer to accomplish. Personal goals encompass a variety of life's endeavors, including academic performance, career achievements, and personal fulfillment. Setting and achieving one's personal goals requires self- monitoring. Examples of academic goals are given below. Strategies for setting and achieving general goals, course and study goals, and career goals are then discussed. Examples of Academic Goals Academic goals do not only include passing a test or earning a certain grade on a project or in a course. A variety of goals related to self-awareness, time management, test taking, writing, study habits, and other aspects of academics may guide students along the path of academic success. The following sample of academic goals is from Michaels, et al. (1988, p. 80-86). Goals Related to Self-Awareness, Self-Monitoring, Self-Advocacy and Problem Solving • I will use grades and test marks to monitor my success in a specific course. • I will identify specific strategies I may use and use those strategies in a consistent manner. • I will realistically evaluate my performance on a specific task and then give myself praise or criticism as that performance warrants. • I will actively involve myself in the learning process by constantly checking information being processed to determine if it makes sense. Goals Related to Test Taking • I will develop an ability to relax before taking tests in order to avoid test anxiety. • I will listen and/or read all directions carefully before beginning an exam. • I will plan an exam budget so I can best monitor and use my time wisely. • When taking essay tests, I will outline what I will say before I begin writing it. • I will save tests when they are returned to use as study guides for future exams. Goals Related to Time Management, Task Attack, and Task Follow-Through • I will estimate the amount of time a given assignment should take. • I will compare actual task completion time with my initial estimate. • I will schedule specific daily study times prior to exams in order to successfully learn materials. • I will work steadily and in a sustained fashion for a given time period (specify ______). • I will task analyze long-term assignments in order to break them into manageable short-term tasks. 17

- 18. • I will decide which of many tasks should be completed first. Goals Related to Study Habits • I will select the main ideas or key points from written paragraphs. • I will study in a distraction-free environment. • I will focus on how newly acquired information relates to previously learned material. • I will use a previewing strategy when reading textbook assignments. • I will use a tape recorder to record class lectures. • I will keep notes and assignments in an organized manner. • I will use mnemonic devices and memory techniques to assist recall and retrieval. Goals Related to Writing • I will demonstrate an ability to write clear, concise, coherent sentences. • I will use a proofreading technique to monitor my written expression. • I will learn to use a word processor in order to edit and correct my written material. • I will use a tape recorder to aid in my retrieval of lecture materials and using the tape I will write down the key ideas to study. • I will use the spelling check with my word processing program to monitor and correct my spelling errors. Goals Related to Reading • I will gain main idea and key information from a textbook chapter. • I will use the context to gain the meaning of unfamiliar vocabulary words. • I will demonstrate an active involvement in the reading process by using a visual imagery technique while reading. • I will use textbooks on tape. • I will use a reading preview strategy to aid comprehension. Goals Related to Mathematics • I will learn to appropriately use the resources available on campus to upgrade my math skills. • I will seek out peer tutoring on campus for difficult mathematical concepts. • I will use my math textbook to locate the solutions to difficult math problems. • I will complete homework assignments in a timely manner. • I will use a calculator so that difficulty with math facts will not impede my ability to solve complicated problems. Goals Related to Social Skills • I will appropriately ask for help or assistance from a fellow student. • I will appropriately ask for help or assistance from an instructor. • I will demonstrate appropriate listening skills. • I will monitor my feelings. • I will appropriately engage in class participation. • I will demonstrate an ability to stand up for my rights. 18

- 19. General Goal-Achieving Strategy Adapted from Aune and Ness (1991), the following goal-setting worksheet helps individuals plot a course of action for achieving a goal. It breaks the goal into several parts, making the goal more manageable, and it delineates time frames for finishing each part. Goal-Setting Worksheet GOAL: Objective 1 Steps to reach Objective 1 Time frame 1. 2. 3. 4. Objective 2 Steps to reach Objective 2 Time frame 1. 2. 3. 4. Objective 3 Steps to reach Objective 3 Time frame 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. GOAL: Improve next test score by one letter grade Objective 1: Steps to reach Objective 1: Time frame: Take better lecture 1. Read assignments before class 1 hour per day notes 2. Take vocabulary list to class 3. Take Xeroxed copies of illustrations to class 4. Ask questions during class 5. Review and reorganize lecture notes Objective 2: Steps to reach Objective 2: Time frame: Meet with instructor 1. Schedule weekly appointment 1 hour per week 2. Review notes and readings before meetings 3. Have specific questions ready 4. Take notes during meeting Objective 3: Steps to reach Objective 3: Time frame: More effective test 1. Make up practice questions 3-4 hours per week preparation 2. Try visual association and mnemonic strategies 3. Work with study group 4. Short, frequent reviews 5. Start preparation two weeks before test Course and Study Goals Strategies 19

- 20. In education, goals are important for guiding one's work. Setting out specific course and study goals helps to motivate one to learn. Developing a realistic plan of action for achieving those goals helps one to avoid procrastination, unnecessary stress, and failure. Walter and Siebert's (1993, p. 50-61) approach to setting and achieving course and study goals is summarized below with some additions. Consider how information about the course may be obtained. • Potential sources of information are: the instructor, academic advisor, course syllabus, course schedules, assigned course materials, course outlines, other students who have taken the course or instructor, class discussions, and student manuals and programs. Set a realistic goal for the course. • In most cases, the goal students set are a particular grade for an assignment or for the entire course. • Be realistic when setting a course grade or an assignment grade as a goal. Consider the following factors when setting grade goals: • Do I have previous experience in or knowledge of this subject? • Am I interested in this subject? • How similar or different are my preferred learning style and the instructor's teaching style? • How does the way the course is graded compare with my preferred way of demonstrating understanding? Determine what types of tasks are required to achieve the goal. • Attending classes? ... How many? • Participating in class? ... In what manner? • Reading the assignments? ... How many? How carefully? • Taking lecture notes? ... How completely? • Writing papers? ... How many pages? How many references? What style or format? Expository or interpretive? • Taking tests or quizzes? ... What minimum scores are needed? • Completing special projects? ... What are the requirements? Set up a study schedule to accomplish each of the required tasks. • Factors to consider when planning a study schedule include: o What steps are involved in each task? o How much time will it take to complete the steps of each task? o When must each goal be completed? o How much can I reasonably expect to do in the time I have? o How much daily work must I do to finish the tasks on time? o Are there specific requirements for completing the tasks? o How will I be required to demonstrate that I have achieved the goals? Record your progress toward completing tasks and reaching your goal. • One way to record progress is with a calendar. o Purchase or design a daily, weekly, and/or monthly calendar. o Think of a short description of each step required to complete each task for achieving the goal. o Record the brief description in the appropriate place on the calendar based on the due dates you identified in the previous step. o Cross off each step and task as they are completed. 20

- 21. • Another way to record progress is with a check list. o Specify each task (or the corresponding steps of each task) required to achieve the goal. o Prioritize the tasks in order of importance and ease of completion. o Determine when each task (or step) should be completed. o Record when each task was actually completed. o Record how you will reward yourself for completing each task. o Record whether or not you rewarded yourself for completing a task. o Record whether or not you rewarded yourself for achieving the goal. o Evaluate your actions against your success at achieving the goal. o A sample check list might look like this (Walter and Siebert, 1993, p. 56): Example Check List for Passing English Test Study Behavior Due Date Date Reward Yes/No Completed 1. Read Chapter 1, generate questions and Sept. 2 . . . answers, write summary 2. Read Chapter 2 (same as #1) Sept. 5 . . . 3. Read Chapter 3 (same as #1) Sept. 9 . . . 4. Read Chapter 4 (same as #1) Sept. 16 . . . 5. Read Chapter 5 (same as #1) Sept. 23 . . . 6. Generate questions from today's class and Sept. 1 . . . take practice quiz 7. Same as #6 Sept. 3 . . . 8. Same as #6 Sept. 5 . . . 9. Same as #6 Sept. 8 . . . 10. Same as #6 Sept. 10 . . . 11. Same as #6 Sept. 12 . . . 12. Same as #6 Sept. 15 . . . 13. Same as #6 Sept. 17 . . . 14. Same as #6 Sept. 19 . . . 15. Same as #6 Sept. 22 . . . 16. Same as #6 Sept. 24 . . . 17. Same as #6 Sept. 26 . . . 18. Generate questions from old test Sept. 10 . . . 19. Make up and take practice test for Ch. 1, 2 Sept. 7 . . . 20. Make up and take practice test for Ch. 3, 4 Sept. 17 . . . 21. Make up and take practice test for Ch. 5 Sept. 24 . . . 22. Make up and take practice test from all Sept. 27 & 28. . . sources of questions 23. Meet with study group to make up practice arrange . . . test 24. Take exam Sept. 29 . . . 25. Achieve goal: Pass exam . . . . Reward yourself for completing tasks and reaching goals. • Rewards might include things like taking a walk, watching a TV show, going to the movies, having a sundae, taking a nap, reading a magazine, or calling a friend. • Take your reward whenever a task is completed on schedule. • Do not reward yourself if a task is not completed on time. • The reward for achieving the goal should be "bigger" than the rewards for completing each task. 21

- 22. Career Goals Strategies Guidelines for assessing one's career interests are quoted from Jewler and Gardner (1993, p. 164-174). When setting career goals, one must consider life goals, personal interests, personal skills, personal aptitudes, personality characteristics, and work values. Opening Questions • In general, what kind of work do you want to do after finishing your education? • What career fields or industries offer opportunities for this kind of work? • What role will college play in preparing you for this work? Will you be required to attend college in order to enter that career field? • What specific things do you plan to do to enhance your chances of getting a job when you graduate? • Do your career goals seem compatible with your other life goals and values? • Is it likely that you will need to transfer to another college in order to get the education you need for your career (Jewler and Gardner, 1993, p. 164)? Consider Your Personal Interests • Take a standardized inventory or test with a career counselor or guidance counselor. • Look through college catalogues for courses that sound interesting. Write down several of them. Note why each course interests you. • Make a list of all the classes, activities, and clubs you enjoyed in high school or since then. Note why each activity interested you. • Write down any activities outside class that you intend to pursue at college (Jewler and Gardner, 1993, p. 166-167). Consider Your Personal Aptitudes • Aptitudes refer to inherent strengths that form the foundation for skills. Aptitudes may be genetic or learned at an early age. • The following table will help to identify personal aptitudes on which you might try to build your career goals. Personal Aptitude Place an asterisk (*) next to your strengths. Place an "x" next to your weaknesses. Place a question mark next to the aptitudes you are not sure about.”?” (Jewler and Gardner, 1993, p. 168) People with strong aptitudes in abstract reasoning can interpret ___ Abstract Reasoning poetry, solve scientific problems in their heads, and solve logic problems. People with strong verbal reasoning can talk through problems ___ Verbal Reasoning easily or can understand the problems more easily when they hear them described than when they see them on paper. People with strong aptitudes in spatial relations are able to ___ Spatial Relations understand the physical relationships between two- and three- dimensional objects or designs. People with strong aptitudes in language usage are able to write ___ Language Usage and speak effectively. People with strong mechanical ability are able to physically ___ Mechanical Ability manipulate the parts of a machine to make it work. People with strong clerical ability are able to do detailed general ___ Clerical Ability office work efficiently and to organize records or accounts. People with strong numerical ability are able to solve arithmetic ___ Numerical Ability problems easily. ___ Spelling People with strong aptitudes in spelling are able to understand 22

- 23. and remember patterns and details. How would you prove you possess your strongest aptitudes? How do they relate to your current skills? • Take a personality assessment, such as the Myers-Briggs Inventory, to determine your personality characteristics • Write down ten words that you would use to describe yourself. Ask a close friend or relative to write down ten words that describe you. How do the lists compare (Jewler and Gardner, 1993, p. 169)? 23

- 24. Teaching (the Catalyst for Learning), Control, Health, Evaluations http://www.muskingum.edu/~cal/database/general/motivation.html Three strategies that make teaching the catalyst for learning are teacher as artist, teacher as technician, and teacher as role model (Hoxmeier, 1987). Teacher as Artist With the "teacher as artist" strategy, the instructor becomes the verbal designer of knowledge in order to motivate students. With this approach, the instructor utilizes a variety of acting techniques, forms of expression, and imagination to involve students in the learning process. Acting techniques include body movements, voice projection, non-verbal forms of communication, and role playing. Humor, whimsy, contentedness, pleasure, and concern are forms of expression that may be employed as catalysts for learning. Imaginativeness involves calling into play all of the senses when conveying knowledge. Teacher as Technician The "teacher as technician" strategy involves teaching to maximize learning. Several approaches may be used individually or in combination to enhance motivation to learn. • Structure course work according to the following scheme: review previous work, preview today's work, teach today's work, practice today's work, review today's work, preview tomorrow's work. • Seek precise examples for main points. • Stimulate interest by emphasizing the value of the new information or by linking it to previous knowledge or personal experiences. • Develop the ability to improvise. • Give students breathing spaces. • Give students the opportunity to ask questions. • Give students the opportunity to answer questions. • Give students the opportunity to share personal experiences. • Be sensitive to students' learning patterns. Teacher as Role Model With the "teacher as role model" strategy, the instructor demonstrates, through everyday practice, the appropriate behaviors that make an effective and motivated learner. The following suggestions help the instructor to become a good role model. • Share personal experiences as they relate to the subject matter. • Demonstrate a love of learning, teaching, and the subject matter. • Demonstrate the relevance of the information by emphasizing the value of the information and its relationships to existing information. • Show students various ways to approach the course material. • Show human feelings. Sense of Control • Motivation levels may be intricately linked to one's sense of control over various aspects of his/her life. Highly motivated persons often have effective time management skills, are organized, have well defined personal goals, and are in control of physical and mental well- being. 24

- 25. Health Concerns Achieving and maintaining high levels of motivation are difficult if an individual is in poor physical or mental health. It is important that one get adequate rest, exercise, and nutrition. One should seek medical attention when ill and professional assistance for sensory deficits. Mental health must be monitored to avoid excessive stress, anxiety, or depression. Individuals can learn relaxation and coping techniques, and they should be familiar with professional counseling services available at school or work. Knowledge of Evaluation Results One of the most neglected areas of motivation intervention is precise knowledge of evaluation results. A common student question is "How am I doing?" Students need to understand clearly and precisely how evaluations were determined and why they received a particular score. Instructors should explain what was done well on an assignment and what is needed for improvement. The more specific the form of evaluation, the more motivational it is for students. Simply reporting a number grade or a letter grade is one of the worst methods of evaluation. That approach offers no positive reinforcement and no guidelines for future reference. Written or oral comments are vastly superior and should always accompany number and letter grades. Relevance, Active Learning, Task Difficulty, Anxiety/Voice Tone Relevance (Make Learning Useful) Often times, students are not interested in a course or lecture because they fail to recognize how the material is relevant to their lives or career plans. This disinterest may translate into a lack of motivation for attending class, taking notes, completing assignments, or participating. Instructors can improve student motivation by making learning more meaningful (Hoxmeier, 1987). Students, under the guidance of facilitators, also can work to increase their own motivation levels by identifying the relevance of course material. Three ways to do so are to emphasize the value of the new information, to establish information links with previous knowledge, and to thoughtfully design assignments. Value of Information One way to make learning more meaningful is to stress the value of the new information. New material may be important socially, economically, culturally, morally, or ethically. The following strategies may be used by instructors and students alike. Instructors may point out how new information is of value to them personally or to a social group, while students may search for the value of the new information in some facet(s) of their own lives. "W" Questions • Consider the value of the information by answering the five "W" questions. Why is the information of value to me or to someone else? What aspects of it are valuable? Where (in what situations) is it valuable? To whom is it valuable? When is the material valuable? Time Frame • Remind others or yourself about the values of the information in the long-term versus the short-term. Is there a difference? Why? 25

- 26. Contextualize • The instructor can describe active situations in which the information was used and he/she can encourage the students to do the same. Make it a group project, or have students keep individual journals over the semester or year. Information Links Instructors or facilitators can help students to link new information with prior knowledge and/or experiences. This motivates students because it aids in establishing the value of information and it is easier to register and recall information associated with existing knowledge. Prior knowledge may derive from other courses, assigned readings, work experiences, social experiences, the media, family, etc. The following strategies help to establish information links. Journals • Encourage students to keep journals in which they record some number of pieces of new information and link them to prior knowledge. They should identify the sources of the prior knowledge if possible. Journals may be kept on a daily or weekly basis. Group Projects • Form small groups of students for establishing links between new and existing knowledge and identifying sources of prior knowledge. Each group may present its results to the rest of the class. Linkage Posters • Have students work individually or in groups to design "linkage posters" with new information and the prior information to which it may be linked. Assignment Design This strategy is intended for use by instructors. Its goal is to help instructors plan effective assignments that stress the relevance of the work rather than assigning "busy work." The guidelines listed below assist the instructor in designing assignments that make learning more meaningful. When designing an assignment, the instructor should ask him/herself the following questions: Is the assignment worthwhile? In what ways is it? Does the assignment seem worthwhile to the students? Are links to prior knowledge gained from required readings or other sources clear? Does the assignment allow students the opportunity to consider and evaluate the relevance of the work? Is the assignment clear to the students? Is the assignment definite? Is the assignment reasonable? Does the student know how to prepare the assignment? Does the student have the necessary skills and background to successfully complete the assignment? 26

- 27. Make Learning Active Student motivation may be increased by making learning more active. This is especially true for kinesthetic learners. Activity improves motivation because in encourages students to use more senses and it increases student involvement. The strategies outlined on the following cards are intended for use by instructors and students alike (Hoxmeier, 1987). Often times, active learning is a cooperative effort between the two. The strategies vary in the amount of instructor intervention and student independence. Direct instruction involves more instructor intervention than discovery strategies. It may be the preferred strategy for difficult learning tasks or physical skills. The phase-in, phase-out method described below is from Singer (1978). Direct Instruction: Phase-In, Phase-Out Method Instructor: Introduce the skill or task to be taught by using description or action. Instructor: Explain the specific steps of the skill or task. Instructor: Demonstrate how the skill works. Instructor and Student(s): Work together on an example of the skill or task. Instructor: Formulate a similar example or problem. Student(s): Apply the new knowledge. Student(s): Restate and explain the basic components of the skill or task. Discovery Strategies: The Problem Method Discovery strategies involve more student involvement than direct instruction. They may be the preferred strategies for critical thinking or problem-solving tasks. The problem method outlined below is from Loomer, Kuhn, and Turner (1977). 1. Learner becomes aware of a problem. 2. Learner defines and delimits the problem. 3. Learner gathers evidence to help solve the problem. 4. Learner forms hypothesis of solution. 5. Learner tests hypothesis. 6. Learner solves the problem or repeats steps 2-5. Level of Task Difficulty The level of difficulty of a task is closely related to anxiety levels and may enhance or inhibit motivation. For best results, the task should be started at an appropriate level of difficulty and the level should be raised a little at a time. If raised too dramatically or started too high, students may become overwhelmed, unsuccessful, and unmotivated. If raised too slowly or initiated too low, students may become bored and loose motivation. A number of factors should be considered when selecting an effective starting point or rate of raising task difficulty. These include student preparation, student capabilities, student interest level, the skills required to complete the task, the nature of the task, and the time allowed for completing the task. 27

- 28. It is helpful to allow for student feedback related to task difficulty. Give students the opportunity to express questions and concerns about initial levels and rates of increase of task difficulty. Ask them to relate these to their own learning styles, capabilities, and levels of preparation. Anxiety and Voice Tone Some level of anxiety, here defined as concern about a learning task, is necessary for learning to occur. Without anxiety, few people would be motivated to complete assignments or to learn. When one considers the relationship between attention and the learning curve, one can see that anxiety and arousal need to be moderately high for learning to occur. In other words, tension and anxiety increase motivation up to a point. However, if anxiety and arousal are too high, too much energy is directed to dealing with the anxiety and learning is inhibited. In sum, then, moderate levels of anxiety may act to motivate individuals to complete learning tasks. The point at which anxiety becomes counterproductive varies by individual. Anxiety may be created by setting deadlines for completing tasks, by increasing the level of difficulty of a task, or by setting goals for specific levels of performance. Such anxiety may be self-generated or imposed by others. Tone of voice is another form of motivation. Pleasant tones have the greatest positive impact on learning. For unresponsive individuals, slightly unpleasant tones may be effective motivators; however, there may be undesirable side effects. Neutral tones, in most situations, have little to no influence on motivation. Self-Talk, Support Systems Self-Talk Self-talk refers to the process of bringing our attitudes to a conscious level. It is what we say to ourselves and it reflects our self-esteem. Self-talk can be negative, positive, or neutral. Learning to engage in encouraging self-talk is an effective motivating strategy. An individual must be his/her own best friend, and to do so involves recognizing one's assets and reminding oneself of them. Students may be exposed to the positive self-talk process by an instructor or facilitator. As they become more proficient in the strategy, they may continue to practice it on their own. Some suggestions for implementing positive self-talk are outlined below; they may be modified to suit individual needs. • Compile a list of individual assets or successes. o The assets could be related to social skills, time management, organization, note taking, communication skills, and work experience. State the positive attributes as clearly and precisely as possible. For example, instead of stating "I have good social skills," say "I am an attentive and compassionate listener." • Select a format for documenting the individual assets or successes. o Some people may choose to simply write a list of the attributes. Other may wish to design a poster, develop a journal, or make a tape recording. Encourage creativity in expression. Utilize as many senses as possible. • Develop a daily routine of referring to the individual assets or successes. o Set aside a special time(s) every day for referring to the list and reminding yourself of personal assets. One need not review the entire list every day. • Make it a habit to refer to the asset list during emotional lows. o Remind yourself that successes have been accomplished in the past and more will be accomplished in the future. • Internalize the asset list so that it may be recalled without the documentation. o Commit the assets and successes to memory so that they may be recalled while walking to an exam or driving to a job interview. • Continually update the list to include new assets that develop as you mature and experience new successes. 28

- 29. Support Systems Sometimes people can't seem to motivate themselves on their own. At other times, self-motivated people falter and need help getting back on track. In these cases it is important to know where to get help when the need arises. Establish a motivational support system at home, at school, and at work. The support system may be as simple as a "buddy system" with a reliable friend or colleague. It may be more complex, encompassing a number of individuals from different aspects of one's life to whom one turns in different situations. People in the support system may be sources of motivational strategies or they may be role models. Check the following sources for motivational support. • family members • guidance counselors or advisors • coaches • resident assistants and directors • faculty members • class mates • peer or professional tutors • religious leaders • civic leaders • work colleagues • friends Creating Interest An important means of increasing motivation is to create interest in a particular learning task or topic. Unfortunately, this may be easier said than done. Methods for creating interest will vary significantly according to personal preferences, personal experience and background, and subject matter. Seven suggestions for adding or creating interest in a task are listed below. For additional information, refer to the Changing Attitudes section of this page. Novelty Get motivated to complete an ordinary or mundane task by adding a little novelty to it. Do the activity backwards. Use a partner or role reversal. This strategy is particularly useful in the initial period of presentation of a task or topic. The task of learning minerals or rocks for geology lab provides a good example of the use of novelty. Students assemble into groups of three to five. Each student in the group is given a different rock and he/she thinks of a name for the rock. Then the students, speaking for the rocks, engage in a conversation that emphasizes the rocks' characteristics. "Hello Bonnie Basalt! You are really dark in color and have small minerals." "That's true Granny Granite. You are much lighter in color than me and you have larger minerals. I really like the pink feldspar in you." Variety Another strategy is to obtain information about the task from a variety of sources. Different perspectives on a subject often help to generate interest. A topic may not seem interesting as it is presented in a book but may be interesting in another format. Don't rely solely on text books or lectures for information, but supplement them with magazine articles, newspaper articles, television shows, radio programs, conversations with students, conversations with other experts or knowledgeable people, museum exhibits, etc. For example, to 29

- 30. learn about the major battles of a war one might read novels, watch movies, attend reenactments, or talk with participants or their descendents. Relevance A third strategy is to recognize how the task is relevant to one's personal experiences and knowledge base (see the Relevance section of this page for more information). Tasks often become more meaningful when one ties them to existing information. Meaningful tasks enhance motivation. For example, relate math geometry equations to your summer job as a construction worker or your experience in ordering carpet or wallpaper. Apply new knowledge about sibling relations from psychology to your own family experiences. Relate geology landscape studies to your farming knowledge. Personalize Making new information personal helps to create interest in uninteresting subjects. Try relating the new information to matters of personal concern. For example, relate what is learned in history class to current political issues with which you are concerned. Relate what is learned in biology class to your opinions about abortion or euthanasia. Relate new sociology information to personal family issues. Actively Use Knowledge Make active use of new knowledge in order to develop and maintain interest in it. Ask questions of yourself, your classmates, and your instructor. Anticipate the next steps in the course. Talk about the new information with friends, family, and classmates. Think about it during that extra free time while walking to class or waiting in line. Write about the new knowledge in a journal, or make up a story using the information. Apply Knowledge Create interest by applying new knowledge learned in one course to another course. Apply new knowledge from school to your job, or new knowledge from your job to school. For example, apply knowledge from chemistry class to the study of rock and mineral composition in geology class. Apply information from history class to a political science course. Information from persuasion may be applied to a marketing course. Work with Others Form study groups or less formal meetings with classmates to discuss new information. Other students often are able to offer new perspectives on information that may be more interesting to you than those presented in class. Other students may share personal experiences related to the new knowledge that you find interesting. Attitudes, Class Attendance, Desire to Learn Changing Attitudes Attitudes greatly influence motivation. Poor attitudes about tasks often translate into lack of motivation. Similarly, positive attitudes usually enhance motivation. Happily, attitudes are plastic and malleable; they can be changed. The following paragraphs offer suggestions for changing attitudes in order to improve motivation. 30

- 31. Attitudes about Task Content When one encounters tasks considered to be uninteresting, a red light should go off. Because it is difficult for most people to get motivated to learn things that they don't find interesting, special efforts must be made to increase interest levels. One way to maintain motivation for completing uninteresting tasks is to constantly remind oneself of the long-term and short-term benefits of completing the task. How will it help in achieving personal goals? How will it lead to further successes? Other strategies for developing an interest in task content include obtaining information from a variety of sources, tying new information to old bodies of knowledge, making new information personal, actively using new knowledge using new knowledge in other classes, working with others, and adding novelty to mundane tasks. In addition to disinterest, lack of motivation may derive from tasks whose content triggers strong negative emotions. For example, a student may have trouble completing a geography assignment about a country in which he/she had a extremely negative experience. In this case, one might attempt to break up the event or experience associated with negative emotions, identify positive aspects of it, and focus on those more positive components. Finally, tasks with morally upsetting content may lead to low motivation levels. This differs from the previous situation in that it involves task content that counters fundamental moral or ethical ideals. For example, it may be difficult to complete a task related to euthanasia if one is strongly opposed to and offended by it. Of the three hindrances to motivation related to task content, this is probably the most difficult to address with learning strategies. Attitudes about Task Type Some people consider certain types of tasks distasteful or they may consider themselves inept at those tasks. Consequently, those people may lack motivation for starting or finishing the tasks. For example, some students strongly dislike speaking in public and will avoid courses or assignments that involve this type of performance. Some instructors believe they are not good at writing grant proposals and they avoid the task. One of the first things to do in this case is to evaluate as objectively as possible individual performance in the specific task(s). It could be that individuals have an inaccurate perception of their abilities to successfully complete a certain task(s). Poor performance may be due to other factors than lack of ability, like lack of preparation or state of health. Set up a mock situation that calls upon the individual to perform the task(s), or use questionnaires to identify mitigating circumstances that may influence one's performance in real-life tasks. For example, a student may feel he/she is a terrible test-taker. This perception may be based on past failures. Another thing one might try is developing a list of reasons why the task is worthwhile. It is often the case that an individual will be motivated to perform a distasteful task because his/her grade or job depends on it. In other cases it is necessary to relate task completion with long-term goals of graduating from school or getting a promotion. Something instructors can do is structure courses so that they include a variety of tasks or they provide for student choices among tasks. For example, give students the choice of turning in a written research paper or giving a formal speech to the class. Write exams with a variety of questions, like multiple choice, fill-in, and essay. Motivation and Class Attendance It is sometimes difficult to get motivated to attend class when one is tired, when one is uninterested in the course, or when one has an early class and isn't a morning person. The following strategies may help one to get motivated to attend class. 31