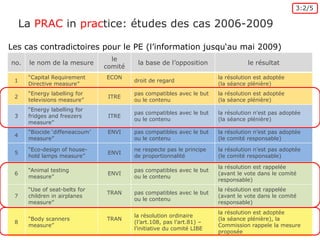

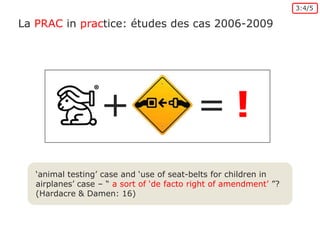

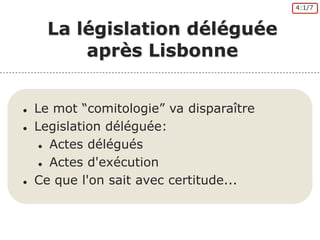

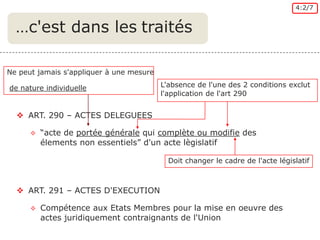

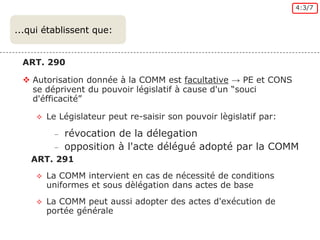

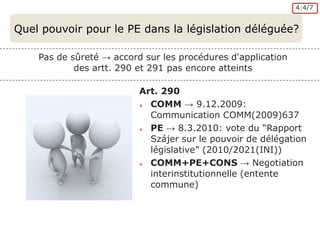

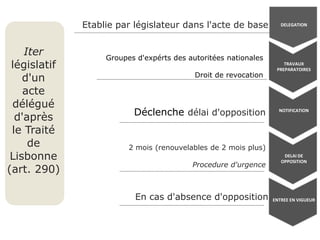

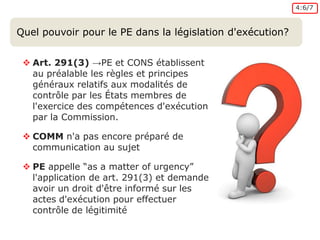

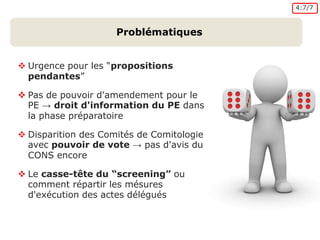

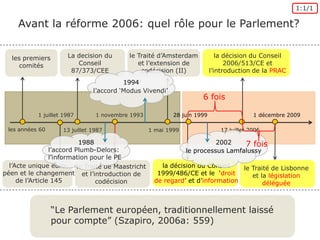

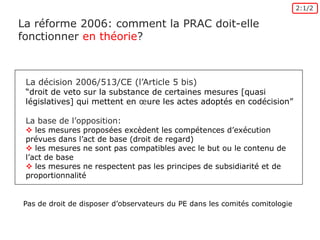

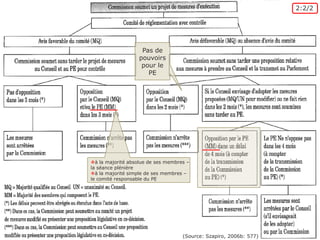

Le document traite de la comitologie et des réformes de 2006 au sein du Parlement européen, en soulignant le rôle limité du Parlement avant et après la réforme. Il analyse la théorie et la pratique de la comitologie, ainsi que les défis posés par la législation déléguée après le traité de Lisbonne. Enfin, il aborde les problèmes d'exécution et le manque de pouvoir d'amendement du Parlement dans le processus législatif.

![2:1/2La réforme 2006: comment la PRAC doit-ellefonctionneren théorie?La décision2006/513/CE (l’Article 5 bis)“droit de veto sur la substance de certainesmesures [quasi législatives] qui mettent en œure les actesadoptés en codécision”La base de l’opposition:les mesures proposées excèdent les compétences d’exécution prévues dans l’act de base (droit de regard)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/comitologie-100310135354-phpapp01/85/La-PRAC-et-le-Traite-de-Lisbonne-6-320.jpg)