5 7 - Active Learning and Reading Course Resource Book

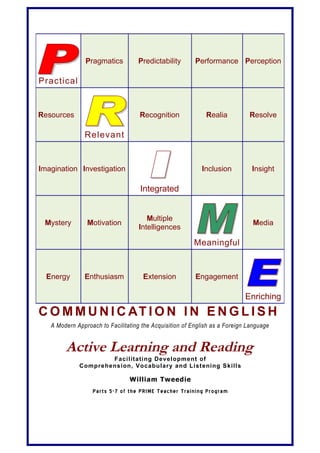

- 1. Pragmatics Predictability Performance Perception Practical Resources Recognition Realia Resolve Relevant Imagination Investigation Inclusion Insight Integrated Multiple Mystery Motivation Media Intelligences Meaningful Energy Enthusiasm Extension Engagement Enriching C O M M U N I C AT I O N I N E N G L I S H A Modern Approach to Facilitating the Acquisition of English as a Foreign Language Active Learning and Reading Facilitating Development of Comprehension, Vocabulary and Listening Skills William Tweedie Parts 5-7 of the PRIME Teacher Training Program

- 2. Active Learning and Reading Facilitating Development of Comprehension, Vocabulary and Listening Skills A Three Part Course Course Resource Book William Tweedie © 2005 - 2010 Kenmac Educan International & William M Tweedie

- 3. TABLE OF CONTENTS PART 1 - FACILITATING COMPREHENSION..........................................................................................................................5 PART 2 - FACILITATING VOCABULARY DEVELOPMENT.............................................................................................................6 PART 3 - FACILITATING READING ↔ LISTENING.................................................................................................................6 ACTIVE LEARNING AND READING - PART 1....................................................................................................7 FACILITATING READING COMPREHENSION...........................................................................................................................7 INTRODUCTION.........................................................................................................................................................7 THE NATURE OF READING............................................................................................................................................7 APPLIED PHONICS...................................................................................................................................................12 WHAT DOES RESEARCH SAY ABOUT READING?...........................................................................................15 OLD AND NEW DEFINITIONS OF READING........................................................................................................................15 IMPORTANT FINDINGS FROM COGNITIVE SCIENCES...............................................................................................................16 IMPORTANT TRENDS IN READING INSTRUCTION...................................................................................................................17 MILESTONES IN READING RESEARCH..............................................................................................................................17 ISSUES OF EQUITY AND EXCELLENCE ..............................................................................................................................18 THE SOCIAL ORGANIZATION OF THE SCHOOL.....................................................................................................................18 ACTIVITIES FOR TEACHERS...........................................................................................................................................18 ACTIVITIES FOR SCHOOLS, PARENTS, AND COMMUNITY MEMBERS............................................................................................19 CHECKLIST FOR EXCELLENCE IN READING INSTRUCTION..........................................................................................................20 THE READING SKILLS PYRAMID ...................................................................................................................25 KEY READING SKILLS & THE STEPS IN ACQUIRING THEM.......................................................................................................25 WHAT IS READING COMPREHENSION?............................................................................................................................27 THE 7 PRIME READING SKILLS......................................................................................................................30 READING SKILL 1: IMAGINING: CONCENTRATING, RELAXING, FOCUSING, VISUALIZING................................31 LEARNING TO CONCENTRATE.......................................................................................................................................31 EXPERIENCING CONCENTRATION....................................................................................................................................31 FREEING UP ATTENTION FOR OTHER THINKING ACTIVITIES.....................................................................................................31 CONCENTRATION EXERCISES........................................................................................................................................33 RELAXATION..........................................................................................................................................................33 FOCUSING............................................................................................................................................................35 VISUALIZING..........................................................................................................................................................35 MEDITATION.........................................................................................................................................................37 READING SKILLS 2 & 3: SKIMMING AND SCANNING.....................................................................................37 SKIMMING AND SCANNING EXERCISE: PULP FRICTION...........................................................................................................38 TEACHING GRAMMAR IN READING.............................................................................................................44 REVIEW OF CAUSE AND EFFECT LINKING WORDS................................................................................................................44 READING SKILL 4: QUESTIONING.................................................................................................................47 PART A - TEACHER QUESTIONS...................................................................................................................................47 PART B - STUDENTS’ QUESTIONS.................................................................................................................................51 THE QUESTIONS OF PREDICTING AND GRAPHIC ORGANIZERS...................................................................................................52 READING SKILL 5: UNDERSTANDING LEXIS - MEANING FROM CONTEXT ......................................................59 KNOWLEDGE ACQUISITION..........................................................................................................................................59 CONTEXT CLUES.....................................................................................................................................................62 MEDIATORS..........................................................................................................................................................67 ANSWER SHEET......................................................................................................................................................70 READING SKILL 5: UNDERSTANDING LEXIS THROUGH INFERENCE...............................................................72 SIMILARITY ...........................................................................................................................................................72

- 4. CONTRAST ...........................................................................................................................................................72 PREDICATION.........................................................................................................................................................72 SUBORDINATION.....................................................................................................................................................73 COORDINATION.......................................................................................................................................................73 SUPERORDINATION ..................................................................................................................................................73 COMPLETION.........................................................................................................................................................73 PART-WHOLE........................................................................................................................................................73 WHOLE-PART........................................................................................................................................................73 EQUALITY.............................................................................................................................................................73 NEGATION............................................................................................................................................................73 WORD RELATIONS...................................................................................................................................................74 NONSEMANTIC RELATIONS..........................................................................................................................................74 READING SKILL 6: REMEMBERING...............................................................................................................74 ABOUT MEMORY....................................................................................................................................................74 READING SKILL 7: READING ALOUD ............................................................................................................79 1. THEORY...........................................................................................................................................................79 2. ILLUSTRATION.....................................................................................................................................................80 3. PRACTICE.........................................................................................................................................................80 ACTIVE LEARNING AND READING - PART 2 ..................................................................................................81 ACTIVE LEARNING AND VOCABULARY ........................................................................................................81 THE STUDY OF WORDS.............................................................................................................................................81 USING A DICTIONARY...............................................................................................................................................82 WORD ROOTS.......................................................................................................................................................82 PREFIXES AND SUFFIXES.............................................................................................................................................83 USE THE WORDS THAT YOU’VE LEARNED...........................................................................................................................86 LEXIS EXERCISES...................................................................................................................................................86 ACTIVE LEARNING AND READING PART 3....................................................................................................89 ACTIVE LEARNING AND DEVELOPING LISTENING SKILLS WHILE READING.....................................................89 THEORY...............................................................................................................................................................89 PRACTICE.............................................................................................................................................................91 12 COMPONENTS OF RESEARCH-BASED READING PROGRAMS ....................................................................92 1. CHILDREN HAVE OPPORTUNITIES TO EXPAND THEIR USE AND APPRECIATION OF ORAL LANGUAGE ........................................................92 2. CHILDREN HAVE OPPORTUNITIES TO EXPAND THEIR USE AND APPRECIATION OF PRINTED LANGUAGE .....................................................93 3. CHILDREN HAVE OPPORTUNITIES TO HEAR GOOD STORIES AND INFORMATIONAL BOOKS READ ALOUD DAILY .............................................93 4. CHILDREN HAVE OPPORTUNITIES TO UNDERSTAND AND MANIPULATE THE BUILDING BLOCKS OF SPOKEN LANGUAGE ....................................93 5. CHILDREN HAVE OPPORTUNITIES TO LEARN ABOUT AND MANIPULATE THE BUILDING BLOCKS OF WRITTEN LANGUAGE ..................................94 6. CHILDREN HAVE OPPORTUNITIES TO LEARN THE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN THE SOUNDS OF SPOKEN LANGUAGE AND THE LETTERS OF WRITTEN LANGUAGE ...........................................................................................................................................................94 7. CHILDREN HAVE OPPORTUNITIES TO LEARN DECODING STRATEGIES ..........................................................................................94 8. CHILDREN HAVE OPPORTUNITIES TO WRITE AND RELATE THEIR WRITING TO SPELLING AND READING .....................................................95 9. CHILDREN HAVE OPPORTUNITIES TO PRACTICE ACCURATE AND FLUENT READING IN DECODABLE STORIES ................................................95 10. CHILDREN HAVE OPPORTUNITIES TO READ AND COMPREHEND A WIDE ASSORTMENT OF BOOKS AND OTHER TEXTS ...................................96 11. CHILDREN HAVE OPPORTUNITIES TO DEVELOP AND COMPREHEND NEW VOCABULARY THROUGH WIDE READING AND DIRECT VOCABULARY INSTRUCTION .........................................................................................................................................................96 12. CHILDREN HAVE OPPORTUNITIES TO LEARN AND APPLY COMPREHENSION STRATEGIES AS THEY REFLECT UPON AND THINK CRITICALLY ABOUT WHAT THEY READ ...........................................................................................................................................................96 SUMMARY............................................................................................................................................................97 REFERENCES..........................................................................................................................................................97 Articles are the property of the authors and copyright owners. Permission is granted for reproduction. Please cite the authors and source.

- 5. Active Learning and Reading Part 1 - Facilitating Comprehension Course Outline 1. Review of the Four Previous Courses a. Prime Task b. Introduction to the course and warm - up c. What is English? How does our definition affect how we facilitate its acquisition by our students? i. Means and Contexts d. What are the Multiple Intelligences identified to date by Howard Gardner? i. Characteristics which reflect MI development in each of us - Learning Styles e. What are the 7 levels of engagement to maximize student and teacher motivation? i. How is Classroom Management affected by the awareness of the 7 levels? f. What are the principles of PRIME Active Learning? i. Why has Project Based Learning proven to be so effective? g. Summary and preview of application of the theory of PRIME Active Learning to Reading Comprehension Instruction. i. Reading Activity : North American Indian Tales 2. Facilitating Reading Comprehension a. Background i. Why don’t the students “get it”? 1. Considerations for Primary and Secondary Students a. A Reading Skills Pyramid b. Skills vs. Strategies i. Basics of reading Activity - see handout ii. The 7 Essential Skills For Understanding Text iii. The 7 Categories of Reading and Learning Strategies 1. Strategy Activities for each Skill

- 6. Part 2 - Facilitating Vocabulary Development Course Outline 1. Lexis a. Words and Word Parts i. For Primary Teaching 1. Applied Phonetics ii. For Secondary Teaching 1. Roots, Pre/Suffixes and more b. Lexical Teaching Activities and Exercises i. It’s all about MEANING! 2. Fun with Words i. Activity Center Worksheets and Games 3. Wrap-up and Reminder: In-school Demonstration Classes Schedule Part 3 - Facilitating Reading ↔ Listening Course Outline 1. Take 2 on the Reading Skills and Strategies 2. Listening Activities a. Book and Tape i. Paying Attention ii. Listening/Reading with an Open Mind iii. Listening/Reading and Reasoning b. If there’s time we’ll play the Time Turbo Game and Others 3. Preparing for your Lesson Demonstrations a. In training b. In schools NOTE: 1. This is a continuation of the course begun in 2005 for the SAME WORKSHOP PARTICIPANTS. 2. Participants should bring a. their ‘textbooks’ from previous workshops b. the Reading Course book for the grade they are currently teaching

- 7. c. a Dictionary Active Learning and Reading - Part 1 Facilitating Reading Comprehension Introduction During the school years and beyond, reading becomes a primary source of new knowledge. As teachers, I’m sure you are aware that being a good reader is essential for academic success. As teachers, you should become aware of the processes that develop while becoming an expert reader. Become aware that, from the perspective of a reading disability, things can go wrong in the development of any one of these processes, causing those which follow to remain underdeveloped. As is most often the case in a reading disability, it is the failure to develop adequate phonemic awareness that is at the root of the disability. Phonemic awareness (PA) is the knowledge that letters represent sounds, and develops roughly between ages 4 and 7. Initially a metacognitive activity, mapping letters to sounds quickly becomes an automated procedure, and effort is no longer required. Catching the kids at risk during these young years can avert the cascading effect reduced PA has on future learning outcomes. The ultimate goal of reading is comprehension. There are numerous strategies available to increase comprehension for all styles of learners. These comprehension strategies are learned and developed after the other reading processes have been mastered. Initializing comprehension strategies remains a metacognitive activity well into adulthood, while the first four reading skills become automated in early childhood. Awareness of the processes of reading, or metacognitive activity, applies primarily at the stage of comprehension; you might ask yourself, “How am I going to apply the strategies I know to get the most out of what I am about to read?”. The Nature of Reading Reading can be summarized by explaining a number of processes: Perceptual processing Word recognition Syntactic processing Semantic processing Metalinguistic processing Comprehension These processes are best described in a developmental framework, describing how the processes emerge through a child’s development. The processes accumulate with age and some continue to develop well into adulthood. Perceptual Processes From infancy perceptual processes develop. These include the ability to transform sound and light waves into meaningful chunks of information. These abilities will be affected by the development of the visual and auditory systems. Being unable to see or hear will drastically affect the development of reading skills as any shortage in either of these areas will respectively reduce their development.

- 8. Perceptual processing begins at the rods and cones situated in the fovea of the eye (see figure 1). This is where light is transformed into electrochemical signals that can be processed by the brain. The fovea is situated near the center of the retina. Immediately surrounding the fovea is the par fovea and beyond that is the periphery. Both the fovea and par fovea are crucial to reading with the par fovea picking up surface information such as letter shape, word shape, spacing, and word length, while the fovea is where the words are identified through their letters. The par fovea primes the brain with surface information just before the meaning is processed. Often par foveal information is enough to recognize a word. When the context suggests that a certain word will follow and the par fovea has identified a word that is the same length and shape as the word predicted, the eyes will likely skip over the word, or words, and fixate on another word two or three to the right. Figure 1 Degrees from Center of the Fovea Figure 1 is a cross-section of an eye, indicating the position of the fovea, a 1 to 2 degree retinal area with the best acuity. Surrounding the fovea is the par fovea, which has lower acuity. As the accompanying graph depicts, visual acuity decreases very rapidly as a letter is projected further from the fovea, in the par fovea, or periphery. One degree of retinal area is about 4-5 letters in width. (From Just & Carpenter, 1987) Word Recognition Words are recognized at two levels: at the letter level and at the word level. At the letter level individual graphemes (letters) are identified and transformed into their phonemic equivalent (their sound). The early reader (4-5 yrs) uses only grapheme to phoneme correspondence at the letter level, having to sound out words in order to string the individual auditory signals into a meaningful word. Two skills precede this. First, knowing that those graphic representations are letters, and second, that strings of letters (words) correspond to spoken words. These skills are acquired through observation: or being read to. It is often observed in early readers, their mimicking the act of reading while not actually reading the words. Young readers (5-7 yrs), after learning that letters represent sounds (phonemic awareness), begin to associate letters with sounds, then learn to blend sounds together, or segment whole words into their individual sounds (see Table 1 for a list of the 40 English phonemes). These are the processes that are addressed in phonics reading programs, and are arguably

- 9. the way early instruction in reading should occur. It is believed that up to 90% of those with reading disabilities have a deficit in phonemic processing. In parallel to learning the sounds of words, a child also learns the shapes of words. This is observed when a child can tell you what a word is but can’t spell it or sound it out with its individual phonemes. This is the process addressed in whole word reading programs, and is arguably the way learning should precede once phonemic awareness has sufficiently developed. It has been suggested that about 10 % of those with a reading disability have a deficit in this area. Table 1 _________________________ ______________________ Consonants Vowels _________________________________ _______________________________ p pill t till k kill ee beet i bit b bill d dill g gill ai bait e bet m mill n nil ng ring oo boot oo foot f feel s seal h heal oa boat o bore v,f veal z zeal l leaf a bat pot/b th thigh ch chill r reef u but o/a ar th thy j, g jill y you i bite a sofa sh, ch shill wh which w witch oi boy aw bout z azure 40 English phonemes (from Fromkin & Rodman 1993) Intermediate readers (7 - 12), with a strong grasp of phonetics, continue to develop their whole word recognition skills through exposure to print. Words that are read many times become recognized by their shape. Their shape is associated with a group of sounds. By 12 a child is highly skilled in both phonetic and orthographic (whole word) encoding or words. Beyond 12, children learn of more advanced skills such as story grammars, writing for an audience, style, and other metalinguistic skills that go beyond word recognition. Syntactic Processing Syntactic processing involves the ability to identify clauses, noun phrases (NP), verb phrases (VP), prepositional phrases (PP), adjectives (Adj), articles (Art), nouns (N), and verbs (V), and assemble them in syntactically acceptable sentences (S). Syntactic development is measured by the “mean length of utterance” (MLU), which is based on the average length of a child’s sentences scored on transcripts of spontaneous speech. Each unit of meaning is recorded which include root words such as “want” and inflections such as “ed” (with the exception of compound words which are classified as one morpheme). Sometime during the second year after a child has about 50 words in his/her vocabulary multiple word utterances begin to appear. These utterances are telegraphic, usually without articles, prepositions, inflection, or any other grammatical modifications. Children also begin to distinguish between actors, objects, and verbs at this time.

- 10. The MLU is closely related to both cognitive and social development, depending on working memory capacity which increases during childhood, and the language used in a child’s surroundings. Adults, and particularly mothers, tend to talk to the child’s level of ability, also speaking in short telegraphic phrases to younger children and increasing the length of their utterances as a child becomes more able to process larger chunks of information, and more complex sentence and meaning structure. By the time children are ready to read they are quite adept with syntactic rules in spoken language and seem to have learned them without effort. They can easily string together words into a grammatically correct sentence. The structure of syntax is described in Figure 2. Sentences are broken down into noun and verb phrases, which are in turn broken down into their constituent parts. The example in Figure 2 is a simple one. Phrase structure trees of this sort can be very complex, though children have little difficulty creating the sentences they represent. Figure 2 Phrase structure tree (From Fromkin & Rodman, 1993) Semantic Processing Semantic processing is developing even before an infant begins to use words. Words initially begin with a single meaning then develop richer meaning as the child is exposed to a wide range of words and experiences. Meaning is assembled in semantic networks in which words are inserted into classes. A dog, for example, may first represent a class of animals with four legs; a child may initially refer to a cat as “dog”. Later these animals will be distinguished from each other and two classes will be form. See Episodic and Semantic memory in Reading Skill 6 Remembering for more about how these classes or schemata develop. These semantic networks, or schemata as they are often called, include more than just linguistic information. They also include images, personal experience, and declarative knowledge (e.g. knowing that a dog has a keen sense of smell because of being told so). These meaning networks may also contain tactual and kinaesthetic information, cognitive processing strategies, and metacognitive strategies. These make up skills, or networks of procedural knowledge. Semantic networks form relatively late, compared to the other aspects of language, and continue to develop throughout life as new things are learned, and

- 11. knowledge is broadened. The development of these networks can be identified through word association tasks, as associated words tend to differ with age. Meanings within a semantic network are activated by each other, referred to as, “spreading activation”. Spreading activation occurs when a particular word is encountered that is related to another. For example, when the word “fall” is encountered, semantically related words such as slip, trip, and autumn are activated to a certain extent, perhaps not to the extent that it enters working memory, but to the extent that if a child was asked “What can you do on an ice rink?”, they may say “slip” before the more common response “skate”. Similarly, if a child, or adult for that matter, is told to say the first word that comes to mind when they hear the word “doctor”, the most closely related word in their semantic network of meanings will be activated rather than some obscurely related or unrelated term. These words may differ depending on the age of the child and thus demonstrate the extent of the child’s knowledge of the word; a young child might say “sucker”, while an older child or adult might say “nurse”, or perhaps “hospital”. Spreading activation helps readers predict the words that will follow based on what has already been read. As described in the section on word recognition within the par fovea, if the predicted word based on spreading activation of a semantic network matches that of the word shape and length information coming in from the par fovea, the word is often skipped over. Figure 3 represents a small piece of the meaning associated with the concept “bird”, representing both typical/atypical instances of the class birds, and typical/atypical properties of those instances of bird. Study the semantic network below for a moment, and develop “feel” for the strengths of the relationships. Add to it. How would the words “cat”, “human”, and “automobile” affect the spreading activation of meaning you are experiencing right now for the word bird? Build on the semantic network below with meaning that has been activated by the three words. In retrospect, how might the spreading activation of meaning differed if I had just offered you only the words cat and human? Figure 3 A portion of the semantic network for the word “bird” - Two effects are demonstrated in the lines and positioning. First, those more typical of a class are joined to the class by shorter lines (red lines- A robin is a more typical bird than a chicken). Second, properties of those instances of the class birds that are most important in the hierarchy of characteristics are connected by shorter lines (black lines - A robin is less likely to be associated with “eggs” than a chicken is). Adapted from Ashcraft (1989)

- 12. Metalinguistic-processing Metalinguistic awareness makes it possible for children to think about language, understand what words are, and define them, or knowing of language as an object or tool that can be manipulated. Metalinguistic awareness begins to develop gradually at a young age, through the middle school years, and continues to develop well into adulthood. It involves the ability to use humour, metaphor, and irony, for example. It also makes possible the use of story grammars, genre, audience, and styles, as reflected in an individual’s writing, to help readers comprehend. These are skills, procedures, and strategies at a reader’s disposal. The ability to choose those that are appropriate, based on a given situation, is metacognitive behaviour. The effective use of skills, procedures, and strategies associated with language involves metalinguistic processing. Comprehension Comprehension involves the use of all of the above processes, especially semantic processing. The act of comprehension is essentially the linking of new knowledge to old knowledge, adding new links and modifying the strength of connections between semantic nodes in a network of meanings. In the early stages of learning to read, comprehension is hampered by limited: capacity of processing space, attention, prior knowledge, and automization of reading processes—all key parts of skilled reading. Applied Phonics There are two major philosophies about the best way to teach phonics in a self-contained classroom. One method, the most commonly used, is "phonics in isolation," for want of a better label. The other system is "applied phonics." Phonics is most often taught as a separate class in which materials such as workbooks, charts, and audio and video-cassettes are used to present the various phonics concepts in a planned sequence. Usually the entire class is taught at the same time. For some this means reviewing much that is already known completely. For others it is one more exposure to concepts that were not learned the first time and are more confusing, or hard to remember, now. Since the class is not involved in reading practice at the time phonics is taught, worksheets or workbooks are assigned to reinforce what the teacher has presented. This style of phonics instruction in isolation is usually difficult for some children to transfer to the actual act of reading, when it is separated from regular reading instruction when silent or oral reading occurs. It has the same effect as the much disliked "round robin" whole language; whole class approach of the 1940s, 1950s, and 1990s, when reading was taught from one book. The one book is usually too easy for many, too hard for several and just right for a few who are learning it for the first time. Applied phonics avoids these traps. Workbooks, worksheets, and tapes are used in centers, if at all. The objective of applied phonics is to develop in the child a habit of reference. Each child draws his or her own phonics need-chart on tag-board by copying elements from commercial charts displayed in the room. First grade teachers using this approach will have screened the entering students to assess their strengths and needs in phonics. The teacher will find that most children will have learned many of the sounds associated with the single consonant letters, for example. Children are required to copy key phonics charts in their own way, so that each has a small version of the rules.

- 13. More about Applied Phonics Each child will have drawn small pictures to illustrate phonics elements. There will be sketches of objects to show the short vowel sounds: possibly apple = /a/, bed = /e/ (or a dot of red, or a horse named ED); igloo = /i/ (or a Native American Indian), octopus = /o/, and an umbrella = /u/. These kinds of pictures have been used effectively for years to remind us of the sound-symbol relationships. Digraph pictures might have a wheel for /wh/, a shoe for /sh/, a church or chair for /ch/, and a thumb for one of the /th/ sounds. Pictures to accompany the ‘hard’ and ‘soft’ g and c would be beneficial- goat for the ‘hard’ g, giant for the ‘soft’ g, cat for the ‘hard’ c, and city for the ‘soft’ c. Pictures are needed for vowels affected by adding an ‘r’: /ar/ could be a star; /or/ could use a horn; /ur/ a turtle; /er/ might be a drawing of a letter and envelope; and the /ir/ could use a bird or a circle. The ou-ow sound could be shown by a house and a cow (surprisingly, the oa-ow sound--boat, scarecrow-is not often a problem and may not have to be included in the child's phonics need-chart). The sounds of /oo/ are needed: oo as in moon, and oo as in book. At the top of the child's chart should be a large drawing of the lower case b and the lower case d. Inside the circle part of the /b/, sketch in a ball to remind the child of the sound of /b/. Inside the circle part of the /d/, draw a dog or duck or doll to remind the child of the sound of /d/. There are other phonics elements that could be drawn in, but the items mentioned here appear again and again as those that need immediate reference while a child is reading. The goal of the chart in applied phonics is to eliminate the need for the chart during oral reading. The charts are to be used by the child as needed during oral reading without prompting from the teacher. This is the practical use of applied phonics. The child brings the small chart to the reading table. The teacher coaches and trains the child to automatically remember to turn to his or her chart when faced with a difficult word in oral reading--rather than guessing or miscalling, as is often the case. Oral reading should not be done until the same selection has been read silently by the child (after new vocabulary has been introduced by the teacher) either a few minutes earlier or during the previous session of reading. The child also may have a chart taped to his or her own desk for easy reference while doing work there. How to Use the Three Phonics Charts (Handouts - 8a, 8b, 8c, 8d) To record phonics chart practices, write a + (plus) next to each correct individual sound symbol, until (++++++++++) ten or more successful practice pluses are accumulated. Each week, the child will have more success if practice is done on at least two consecutive days. Then (after ten pluses) move the student to the next phonics chart. Continue until the child knows all phonics items on the second chart, and then on the third page, which does not show any illustrations. Use the plus system here as well. Identified M.R. students typically need more practice sessions than their peers with "average intelligence". VERY IMPORTANT AT ALL TIMES: Do not give a plus for voiced sounds meant for voiceless or whispered consonants (so that word-part sounds are not distorted). Some teachers have found that whispering all consonant sounds is helpful, as it avoids the voiced "uh" sound which has often been incorrectly added to such consonant sounds as b, c, d, f, g, h, j, k, 1, m, n, p, s, t, v, w, y, and z. (Voiceless consonants are always whispered in speech: c, f, h, k, p, q, s, t, as well as two-consonant symbols such as ch, sh, and wh [although wh is often voiced as /w/ by many teachers and others, and is considered acceptable in Webster’s Dictionary as an alternative]).

- 14. If needed, you may discuss making the sounds correctly by calling 360-665-3708. Remember, phonics is simply a tool to help the student sound out unknown words and it should be done in an easy and relaxed manner. Genuine praise is critical for all correct responses. If a student makes a mistake, say "Good try. We'll get it next time." Gently help the student to understand what the correct response should be. Here are some hints for use: Have student voice the sound. If acceptable, pencil in a plus (+) near the picture. Ten pluses for each sound will equal mastery and readiness for Phonics Chart 2. What is an acceptable sound? Be sure /sh/ and /ch/ are whispered, not voiced, for instance, and /ow/ has two sounds (oh & ou); and er, or, ar, ir, ur all sound like /er/ at times, but ar also says /ar/ and or says /or/. From http://www.ldrc.ca/contents/view_article/148/

- 15. What Does Research Say about Reading? R.A. Knuth and B.F. Jones NCREL, Oak Brook, 1991 In 1985, David Pearson referred to "the comprehension revolution." In essence, he was talking about the movement from traditional views of reading based on behaviorism to visions of reading and readers based on cognitive psychology. Major findings from cognitive psychology regarding: These findings were developed by NCREL in collaboration with a Content Partner, the Center for the Study of Reading, University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign, and the participants in Program 1, "Children as Strategic Readers." The traditional view of the learner as an "empty" vessel to be filled with knowledge from external sources is exemplified by this statue at the University of Leuven (Belgium). Old and New Definitions of Reading Traditional Views New Definition of Reading Research Base Behaviorism Cognitive sciences Goals of Reading Mastery of isolated facts and skills Constructing meaning and self- regulated learning Reading as Mechanically decoding words; An interaction among the reader, the Process memorizing by rote text, and the context Learner Passive; vessel receiving Active; strategic reader, good strategy Role/Metaphor knowledge from external sources user, cognitive apprentice. Reprinted from the Guide to Curriculum Planning in Reading with permission from the Wisconsin Department of Public Instruction Comprehension results from an interaction among the reader, the strategies the reader employs, the material being read, and the context in which reading takes place.

- 16. Important Findings from Cognitive Sciences Most of the knowledge base on this topic comes from studies of good and poor readers. However, some of it is derived from research on expert teachers and from training studies. 1. Meaning is not in the words on the page. The reader constructs meaning by making inferences and interpretations. 2. Reading researchers believe that information is stored in long-term memory in organized "knowledge structures." The essence of learning is linking new information to prior knowledge about the topic, the text structure or genre, and strategies for learning. 3. How well a reader constructs meaning depends in part on metacognition, the reader's ability to think about and control the learning process (i.e., to plan, monitor comprehension, and revise the use of strategies and comprehension); and attribution, beliefs about the relationship among performance, effort, and responsibility. 4. Reading and writing are integrally related. That is, reading and writing have many characteristics in common. Also, readers increase their comprehension by writing, and reading about the topic improves writing performance. 5. Collaborative learning is a powerful approach for teaching and learning. The goal of collaborative learning is to establish a community of learners in which students are able to generate questions and discuss ideas freely with the teacher and each other. Students often engage in teaching roles to help other students learn and to take responsibility for learning. This approach involves new roles for teachers. Characteristics of Poor/Successful Readers Characteristics of Poor Readers Characteristics of Successful Readers Think understanding occurs form "getting Understand that they must take the words right," rereading. responsibility for construction meaning using their prior knowledge. Use strategies such as rote memorization, Develop a repertoire of reading strategies, rehearsal, simple categorization. organizational patterns, and genre. Are poor strategy users: Are good strategy users: • They do not think strategically about • They think strategically, plan, how to read something or solve a monitor their comprehension, and problem. revise their strategies. • They do not have an accurate sense • They have strategies for what to do of when they have good when they do not know what to do. comprehension readiness for assessment. Have relatively low self-esteem. Have self-confidence that they are effective learners; see themselves as agents able to actualize their potential.

- 17. See success and failure as the result of luck See success as the result of hard work and or teacher bias. efficient thinking. Important Trends in Reading Instruction 1. Linking new learning to the prior knowledge and experiences of students. (In contexts where there are students from diverse backgrounds, this means valuing diversity and building on the strengths of students.) 2. Movement from traditional skills instruction to cognitive strategy instruction, whole language approaches, and teaching strategies within the content areas. 3. More emphasis on integrating reading, writing, and critical thinking with content instruction, wherever possible. 4. More organization of reading instruction in phases with iterative cycles of strategies: Preparing for reading—activates prior knowledge by brainstorming or summarizing previous learning; surveys headings and graphics; predicts topics and organizational patterns; sets goals/purpose for reading; chooses appropriate strategies. Reading to learn—selects important information, monitors comprehension, modifies predictions, compares new ideas with prior knowledge, withholds judgement, questions self about the meaning, connects and organizes ideas, and summarizes text segments. Reflecting on the information—reviews/summarizes the main ideas from the text as a whole, considers/verifies how these ideas are related; changes prior knowledge according to new learning; assesses achievement or purpose for learning; identifies gaps in learning; generates questions and next steps. Milestones in Reading Research 1. Evidence that meaning is not in the words, but constructed by the reader. 2. Documentation that instruction in the vast majority of classrooms is text driven and that most teachers do not provide comprehension instruction. 3. Documentation that textbooks were very poorly written, making information in them difficult to learn; subsequent response of the textbook industry to include real literature, longer selections, more open-ended questions, less fragmented skills, and "more considerate" text. 4. Changes in reading research designs from narrowly conceived and well-controlled laboratory experiments with college students to (1) broadly conceived training studies using experimenters and real teachers in real classrooms and (2) studies involving teachers as researchers and colleagues in preservice and inservice contexts. 5. Publication of A Nation of Readers reaching out to parents, policymakers, and community members as legitimate audiences for direct dissemination of research information. 6. Involvement of state education agencies in textbook selection, promoting "the new definition of reading," and developing state-wide assessment programs that are research based; especially important are programs in Michigan, Wisconsin, and Illinois which have longer passages, more focus on comprehension, more than one right answer, strategy use, and assessment of prior knowledge.

- 18. 7. Increasing dissatisfaction with standardized methods of assessing reading. (Consequently, there has been a movement to develop alternative assessment strategies including miscue analysis, portfolios, and projects in the classroom.) Issues of Equity and Excellence 1. Although many students at risk come to school lacking in prior knowledge that is relevant to school achievement, teachers and schools do make a substantial difference. That is, providing students at risk with high quality instruction can drastically alter their academic performance. 2. Although pullout programs and tracking may be well intended, reading researchers increasingly argue that such programs may actually create or extend inequities by segregating students at risk in poor quality programs. Indeed, some researchers contend that the learned helplessness that may characterize students at risk is a functional response to the demands of a dysfunctional situation. 3. An increasing amount of research indicates that student access to functional adult role models is vital for the development of self-esteem and metacognitive abilities. This can come from adult tutors or opportunities for students to participate in the world of work through work/study, shadowing, and apprenticeship programs. The Social Organization of the School 1. Approaches that teach reading as thinking (strategic reading) need time to develop so that teachers can adopt new beliefs, experiment with research-based methods, and refine new practices. This suggests that schools need to provide (a) sustained staff development programs which provide mentoring and coaching, and (b) environments that support experimentation and risk-taking. 2. Reading performance is enhanced when schools have semipermeable boundaries. That is, when: o Parents and other community members are involved in the life of the school as tutors, local experts, role models, and aides in schools. o Students and teachers have opportunities for learning out of school. o Community members take part in the redesign process. Activities for Teachers The examples of excellence in this program clearly show that in world class schools teaching is a multidimensional activity. One of the most powerful of these dimensions is that of "teacher as researcher." Not only do teachers need to use research in their practice, they need to participate in "action" research in which they are always engaging in investigation and striving for improved learning. The key to action research is to pose a question or goal, and then design and implement actions and evaluate progress in a systematic, cyclical fashion as the means are carried out. Below are four major ways that you can become involved as an action researcher. 1. Use the checklist found at the end of this section to evaluate your school and teaching approaches. 2. Implement the models of excellence presented in this program. Ask yourself: o What outcomes do the teachers in this program accomplish that I want my students to achieve? o How can I find out more about the model classrooms? o Which ideas can I most easily implement in my classroom?

- 19. o What will I need from my school and community? o How can I evaluate progress? 3. Form a team and initiate a research project. A research project can be designed to generate working solutions to a problem. The issues for your research group to address are: o What is the problem or question you wish to solve? o What will be our approach? o How will we faithfully implement the approach? o How will we assess the effectiveness of our approach? o What is the time frame for working on this project? o What resources do we have available? o What outcomes do we expect to achieve? 4. Investigate community needs and integrate solutions within your class activities. Relevant questions include: o What needs does the community have in terms of reading and writing? o What can be done (for example, training) by my class to meet community needs? o What skills and resources does the community have that could benefit my students? o What kind of relationships can my class forge with the community? 5. Establish "Community of Learners" support groups consisting of school personnel and community members. The goals of these groups are to: o Share teaching and learning experiences both in and out of school. o Discuss research and theory related to learning. o Act as mentors and coaches for one another. o Connect goals of the community with goals of the school. Activities for Schools, Parents, and Community Members The following are activities that groups such as your PTA, church, and local Chamber of Commerce can do together with your schools. 1. Visit your school informally for discussions using the checklist below. 2. Consider the types of contributions community groups could offer: o Chamber of Commerce groups could sponsor field trips or opportunities for storytelling. o Businesses could buy collections of literature for schools in need. o Churches could sponsor reading groups to help motivate adults to read. o Local fraternal organizations could help tutor students and provide a place for them to read. 3. Consider ways that schools and community members can work together to provide: o Materials for a rich learning environment (e.g., real literature in print and audio form, computers).

- 20. o Opportunities for students and teachers to learn out of school. o Opportunities for students to access adults as role models, tutors, aides, and local experts. o Opportunities for students to provide community services such as surveys, newsletters, plays, and tutoring. o Opportunities for students to participate in community affairs. o Opportunities for administrators, teachers, or students to visit managers and company executives. 4. Promote school and community forums to debate the national goals: o Involve your local television and radio stations to host school and community forums. o Have "revolving school/community breakfasts" (community members visit schools for breakfast once or twice a month, changing the staff and community members each time). o Gather information on the national goals and their assessment. o Gather information on alternative models of schooling. o Gather information on best practices and research in the classroom. Some of the important questions and issues to discuss in your forums are: o Review the national goals documents to arrive at a common understanding of each goal. o What will students be like who learn in schools that achieve the goals? o What must schools be like to achieve the goals? Do we agree with the goals, and how high do we rate each? What is the reason for the pessimism about their achievement? How are our schools doing now in terms of achieving each? Why is it important for us to achieve the goals? What are the consequences for our community if we don't achieve them? 5. What assumptions are we making about the future in terms of Knowledge, Technology and Science, Humanities, Family, Change, Population, Minority Groups, Ecology, Jobs, Global Society, Social Responsibility? Discuss in terms of each of the goal areas. 6. Consider ways to use "Children as Strategic Readers" to promote understanding and commitment from school staff, parents, and community members for strategic reading. Checklist for Excellence in Reading Instruction The items below are based on the best practices of the teachers and researchers in Program 1. The checklist can be used to look at current practices in your school and to jointly set new goals with parents and community groups. Vision of Learning • Meaningful learning experiences for students and school staff. • High enjoyment of reading, writing, and learning.

- 21. • Restructuring to promote learning in the classroom. • High expectations for learning for all students. • A community of readers in the classroom and in the school. • Teachers and administrators committed to achieving the national goals. Curriculum and Instruction • Curriculum that calls for a diversity of real literature and genre, a repertoire of learning strategies and organizational patterns for text passages. • Collaborative teaching and learning involving student-generated questioning and sustained dialogue among students and between students and teachers. • Teachers building new information on student strengths and past experiences. • Authentic tasks in the classroom such as writing letters, keeping journals, generating plays, author conferences, genre studies, research groups, sharing expertise, and so on. • Opportunities for students to engage in learning out of school with community members. • Real audiences (E.g., peers, community members, other students). • Homework that is challenging enough to be interesting but not so difficult as to cause failure. • Appreciation and respect for multiple cultures and perspectives. • Rich learning environment with places for children to read and think on their own. • Instruction that enables readers to think strategically. Assessment and Grouping • Performance-based assessment such as portfolios that include drafts and projects. • Multiple opportunities to be involved in heterogeneous groupings, especially for students at risk. • Public displays of student work and rewards. Staff Development • Opportunities for teachers to attend conferences and meetings for reading instruction. • Teachers as researchers, working on research projects. • Teacher or school partnerships/projects with colleges and universities. • Opportunities for teacher to observe and coach other teachers. • Opportunities for teachers to try new practices in a risk-free environment. Involvement of the Community • Community members' and parents' participation in reading instruction as experts, aides, guides, and tutors. • Active involvement of community members on task forces for curriculum, staff development, assessment and other areas vital to learning.

- 22. • Opportunities for teachers and other school staff to visit informally with community members to discuss the life of the school, resources, and greater involvement of the community. Policies for Students at Risk • Students at risk integrated into the social and academic life of the school. • Policies/practices to display respect for multiple cultures and role models. • Culturally unbiased assessment practices. Important Reading Resources Reading Recovery Program is a supplementary reading and writing program for first- graders who are at risk of reading failure. Reading Recovery was originally developed by New Zealand educator and psychologist Marie M. Clay. It was implemented in Ohio and is now employed in several other states. The short-term goal is to accelerate children's progress in learning to read. The long-term goal is to have children continue to progress through their regular classroom instruction and independent reading, commensurate with their average peers, after the intervention is discontinued. Success is contingent upon the intensive, individual instruction provided by a specially trained teacher for 30 minutes daily. Illinois Reading Recovery Project, Center for the Study of Reading, 51 Gerty Drive, Champaign, IL 61820 (217/333-7213). Teaching Reading: Strategies from Successful Classrooms is a set of six videotapes and accompanying viewer's guides developed by the Center for the Study of Reading. Each tape presents in-depth analyses of successful classrooms. The programs focus on exemplary teachers and students in order to provide viewers with real access to knowledge about effective reading practices. The aim of the program is to provide simulated field experiences for use in college-level education courses for preservice teachers and inservice workshops for practicing teachers. The classrooms featured are: • Emerging Literacy, Ann Hemmeler (Kindergarten), Neal Elementary, San Antonio, TX. • The Reading/Writing Connection, Dawn Harris Martine (second), Mahalia Jackson Elementary, Harlem, NY. • Teaching Word Identification, Marjorie Downer (second/third), Benchmark Elementary, Media, PA. • Literacy in Content Area Instruction, Laura Pardo (third), Allen Street Elementary, Lansing, MI. • Fostering a Literate Culture, Kathy Johnson (third), East Park Elementary, Danville, IL. • Teaching Reading Comprehension: Experience and Text, Joyce Ahuna-Ka'ai'ai (third), Kamehameha Elementary, Honolulu, HI. • Center for the Study of Reading, 51 Gerty Drive, Champaign, IL 61820 (217/333-2552). Rural Wisconsin Reading Project (RWRP) was a three-year project developed by NCREL, the Wisconsin Department of Public Instruction, and the Wisconsin Educational Communications Board that provided technology-supported staff development on strategic reading and teaching for 17 rural districts in central and west-central Wisconsin. The project's approach to develop strategic reading instruction was to treat human and organizational change as a long-term, evolutionary process rather than as a process of implementing an innovation. Two programs have arisen out of RWRP: (1) The Rural Schools Reading Project which applies what was learned from RWRP to address the access, time, and cost challenges of sustained, effective staff development for a network of rural schools

- 23. (this project is on the list of programs that work from the National Diffusion Network of the U.S. Department of Education), and (2) The Strategic Reading Project which is a single school application of the RWRP principles. NCREL, 1120 Diehl Road, Naperville, IL 60563 (630/649-6500). Reciprocal Teaching is an instructional strategy for teaching strategic reading developed by Annemarie Sullivan Palincsar that takes place in the form of a dialogue between teachers and students. In this dialogue the teacher and students take turns assuming the role of teacher in leading the dialogue about a passage of text. Four strategies are used by the group members in the dialogue: summarizing, question generating, clarifying, and predicting. At the start the adult teacher is principally responsible for initiating and sustaining the dialogue through modelling and thinking out loud. As students acquire more practice with the dialogue, the teacher consciously imparts responsibility for the dialogue to the students, while becoming a coach to provide evaluative information and to prompt for more and higher levels of participation. Annemarie Palincsar, 1360 FEB, University of Michigan, 610 East University Drive, Ann Arbor, MI 48109 GLOSSARY Coaching - Providing support in studying new skills, polishing old ones, and encouraging change. Collaborative Groups - A temporary grouping structure used primarily for developing attitude outcomes. Students of varying abilities work together to solve a problem or to complete a project. Comprehension Monitoring - Good comprehenders self-evaluate how well they understand while they read. If comprehension is not proceeding well, they have strategies for going back and improving their comprehension. Constructing Meaning from Text - A process in which the reader integrates what is read with his or her prior knowledge. Cooperative Learning - Students working together in small heterogeneous groups to achieve a common goal. Heterogeneous Groups - Groups composed of students who vary in several ways (for example, different reading levels). Homogeneous Groups - Groups composed of students who are alike in one or more ways. Interactive Phase - Sometimes called "guided practice" in this phase, the teacher attempts gradually to move students to a point where they can independently use strategies. It is a major part of a lesson. Metacognition - The process of thinking about and regulating one's own learning. Examples of metacognitive activities include assessing what one already knows about a given topic before reading, assessing the nature of the learning task, planning specific reading/thinking strategies, determining what needs to be learned, assessing what is comprehended or not comprehended during reading, thinking about what is important and unimportant, evaluating the effectiveness of the reading/thinking strategy, revising what is known, and revising the strategy. Modeling - Showing a student how to do a task with the expectation that the student will then emulate the model. In reading, modeling often involves talking about how one thinks through a task. Predicting - Anticipating the outcome of a situation.

- 24. Prior Knowledge - The sum total of what the individual knows at any given point. Prior knowledge includes knowledge of content as well as knowledge of specific strategies and metacognitive knowledge. Scaffolding Instruction - Providing teacher support to students by modeling the thought processes in a learning episode and gradually shifting the responsibility for formulating questions and thinking aloud to the students. Strategic Learner - A learner who analyzes the reading task, establishes a purpose for reading, and then selects strategies for this purpose. Strategies - Any mental operations that the individual uses, either consciously or unconsciously, to help him- or herself learn. Strategies are goal oriented; that is, the individual initiates them to learn something, to solve a problem, or to comprehend something. Strategies include, but are not limited to, what have traditionally been referred to as study skills such as underlining, note taking, and summarizing, as well as predicting, reviewing prior knowledge, and generating questions. Text - Any segment of organized information. Text could be a few sentences or an entire section of a chapter. Typically, text refers to a few paragraphs. References Allington, R.L. (1991). How policy and regulation influence instruction for at-risk learners: Why poor readers rarely comprehend well and probably never will. In L. Idol, & B.F. Jones (Eds.), Educational Values and Cognitive Instruction: Implications for Reform (pp. 273-296). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum. Anderson, R.C., Osborn, J., & Tierney, R.J. (Eds.). (1984). Learning to read in American schools: Basal readers and content texts. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum. Anderson, R.C., Spiro, R.J., & Montague, W.E. (Eds.). (1977). Schooling and the acquisition of knowledge. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum. Anderson, R.C., Hiebert, E.H., Scott, J.A., & Wilkinson, I.A.G. (1985). Becoming a nation of readers: The report of the Commission on Reading. Urbana, IL: University of Illinois. Banathy, B.H. (1990). Systems design of education: A journey to create the future. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Educational Technology Publications. Borkowski, J.G., Carr, M., Rellinger, E., & Pressley, M. (1990). Self-regulated cognition: Interdependence of metacognition, attributions, and self-esteem. In B.F. Jones (Ed.), Dimensions of thinking: Review of research (pp.53-92). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum. Brown, A.L., Palincsar, A.S., & Purcell, L. (1986). Poor readers: Teach, don't label. In U. Neisser (Ed.), The academic performance of minority children: New perspectives (pp. 105-143). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum. Collins, A., Brown, J.S., & Newman, S. (1989). Cognitive apprenticeship: Teaching students the craft of reading, writing, and mathematics. In L.B. Resnick (Ed.), Knowing, learning, and instruction: Essays in honor of Robert Glaser. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum. Durkin, D. (1984). Do basal manuals teach reading comprehension? In R.C. Anderson, J. Osborn, & J. Tierney (Eds.), Learning to read in American schools: Basal readers and content texts (pp. 39-38). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum. Durkin, D. (1978-79). What classroom observations reveal about reading comprehension instruction. Reading Research Quarterly,15, 481-533. Herber, H.L. (1985). Developing reading and thinking skills in content areas. In J.W. Segal, S.F. Chipman, & R. Glaser (Eds.), Thinking and learning skills: Vol. I. Relating instruction to research (pp. 297-316). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

- 25. Jones, B.F., Palincsar, A.S., Ogle, D.S., & Carr, E.G. (1987). Strategic teaching and learning: Cognitive instruction in the content areas. Alexandria, VA: Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development. Jones, B.F. & Pierce, J. (in press). Students at risk vs. the Board of Education. In A. Costa & J. Bell (Eds.), Mind Matters: Vol. I. Educating for the 21st century. Palatine, IL: Skylight Publishing. Palincsar, A. (1987, April). Collaborating for collaborative learning of text comprehension. Paper presented at the annual meeting of the American Educational Research Association, Washington, DC. Paris, S.G., & Winograd, P. (1990). How metacognition can promote academic learning and instruction. In B.F. Jones, & L. Idol (Eds.), Dimensions of thinking and cognitive instruction (pp. 15-52). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum. Pearson, P.D. (1985). Changing the face of reading comprehension instruction. The Reading Teacher, 39, 724-737. Pressley, M., Borkowski, J.G., & Schneider, W. (1987). Good strategy users coordinate metacognition, strategy use and knowledge. In R. Basta & G. Whitehurst (Eds.), Annals of Child Development, 4, 89-129. Resnick, L.B. (1987). Learning in school and out. Educational Researcher, 16(9), 13-20. Strickland, D.S. (1987). Using computers in the teaching of reading. New York: Teachers College Press. Tierney, R.J., & Cunningham, J.W. (1984). Research on teaching reading comprehension. In P.D. Pearson (Ed.), Handbook of reading research (pp. 609-656). New York: Longman. Weinstein, C.E., Goetz, E., & Alexander, P. (1988). Learning and study strategies: Issues in assessment, instruction, and evaluation. New York: Academic Press. Wiggins, G. (1989). A true test: Toward more authentic and equitable assessment. Phi Delta Kappa, 70, 703-714. info@ncrel.org Copyright © North Central Regional Educational Laboratory. All rights reserved. The Reading Skills Pyramid Key Reading Skills & the Steps in Acquiring Them Learning to read is an exciting time for children and their families. While thrilled by their children's emerging literacy and reading skills, many parents are surprised to learn that reading is not automatic and that, regardless of family background, children require support in learning to read and developing strong reading skills. Most adults forget that acquiring reading skills required skilled instruction. A language-rich environment forms a solid foundation on which reading skills including decoding, fluency, vocabulary, and comprehension are based. Mastery of decoding comprises understanding print concepts, phonemic awareness and phonics and is usually attained by the end of second grade. Some skills, such as vocabulary development, will grow as long as children are challenged by involvement in a rich language environment and by tackling increasingly complicated texts. Research shows that children who develop phonemic awareness and letter-sound knowledge early on are more likely to be strong, successful readers. Children build these skills by reading aloud, practicing nursery rhymes, and playing letter and word games. Tutoring or structured computer programs can also effectively reinforce these skills. Based

- 26. on an understanding of phonemic (or phonological) awareness and basic print concepts, children are ready to learn phonics and to start decoding words. The Reading Skills Pyramid visually depicts the patterns of concept acquisition that children follow in becoming successful readers up through third grade. We recommend a high level of parent involvement in this process by providing high quality educational materials, establishing a pattern of daily reading, creating a rich language environment, and discussing your child's progress with teachers and following up on their recommendations. While most children follow the same sequence of acquiring literacy skills, they do so at their own pace. All children are different: if you have questions or concerns about your child's progress in reading, contact his or her teacher. The five key areas in learning to read are phonemic awareness, phonics, comprehension, vocabulary, and fluency. Phonemic Awareness is an important pre-reading skill. Phonemic awareness deals with the structure of sounds and words. Phonemic awareness is the understanding that words are made up of sounds which can be assembled in different ways to make different words. Once a child has phonemic awareness, they are aware that sounds are like building blocks that can be used to build all the different words. Phonemic Awareness overlaps and is often confused with phonological awareness. Phonological Awareness is the ability to distinguish distinct sounds. Children without phonological understanding might not have learned to hear the difference between three or free, lice or rice, meat or neat. Phonological is another important prereading skill which also must be learned and practiced. Children build phonemic awareness and other pre-reading skills by practicing nursery rhymes and playing sound and word games. Common exercises to develop phonemic awareness include games with rhymed words, games based on recognizing initial consonance. Tutoring, workbooks, games, or structured computer programs can help teach or reinforce these skills. Parents help in this process by providing high-quality educational materials, establishing a pattern of daily reading, and creating a rich language environment. As phonemic awareness is developed, children should become interested in how words are portrayed in print. Daily reading sessions with the children following along should help develop their understanding of print concept and feed this curiosity. This interest in decoding the words is the fuel for children learning the alphabet and phonics decoding skills. Phonics is the understanding of how letters combine to make sounds and words. Phonics curriculum usually starts with teaching letters, slowly creating a working knowledge of the alphabet. Children learn the sounds of each letter by associating it with the word that starts with that sound. Phonics skills grow through reading activities, and students learn to distinguish between vowels and consonants and understand letter combinations such as blends and digraphs. While a phonics curriculum is a critical step in learning to read, many parents and educators forget that before you can succeed with a phonics curriculum, you must teach phonemic and phonological awareness. Phonemic awareness involves the understanding of the relationship between sounds and words. Phonemic awareness is the understanding that words are made of sounds that can be used, like reusable building blocks, to construct words (h + at = hat, f + at = fat, etc). Phonological awareness is another pre-phonics skill that trains a child's ear to discriminate between similar sounding sounds (with phonemic awareness, children will distinguish between "three" from words like "free" or "tree"). Contrary to popular belief, phonemic awareness does not appear when young children are learning to talk, because this pre-phonics skill not necessary for speaking and understanding

- 27. spoken language. However, phonemic awareness is critical for a successful phonics curriculum. What is Reading Comprehension? Reading comprehension skills separates the "passive" unskilled reader from the "active" readers. Skilled readers don't just read, they interact with the text. To help a beginning reader understand this concept, you might make them privy to the dialogue readers have with themselves while reading. Skilled readers, for instance: 1. Predict what will happen next in a story using clues presented in text 2. Create questions about the main idea, message, or plot of the text 3. Monitor understanding of the sequence, context, or characters 4. Clarify parts of the text which have confused them 5. Connect the events in the text to prior knowledge or experience Reading comprehension skills increase the pleasure and effectiveness of reading. Strong reading comprehension skills help in all the other subjects and in the personal and professional lives. The high stake tests that control advancement through elementary, middle, and high school and which determine entrance to college are in large parts, a measure of reading comprehension skills. And while there are test preparation courses which will provide a few short-cuts to improve test-taking strategies, these standardized tests tend to be very effective in measuring a readers reading comprehension skills. In short, building reading comprehension skills requires a long term strategy in which all the reading skills areas (phonics, fluency, and vocabulary) will contribute to success. "My student reads but she doesn't seem to really "get it". By "reads", the teacher means that the child is successfully decoding words but decoding without reading comprehension will not get you far. Building vocabulary words is key to reading, to writing, to verbal expression, and in many ways, vocabulary is key to building analytical and critical thinking. A person's vocabulary skills can be measured in terms of building receptive vocabulary (ie understanding) words and their expressive vocabulary words. People can build their expressive vocabulary in two ways that can get measured: the written vocabulary words or their spoken vocabulary words. Building vocabulary skills improves reading comprehension and reading fluency. Without building a large vocabulary, students cannot read successfully. Building vocabulary is far more than memorizing words. Ideally, children should be brought up in a rich language environment which is language- and word- conscious. Children take up attitudes and learn from their parents so building vocabulary starts as a family affair. Children are greatly influenced generally by the amount of conversation, by the nature of the conversation (and the vocabulary used), and the "word awareness" of the family. There are a great number of families where vocabulary word games are played with the children as an ongoing game to build vocabulary and "word awareness" skills including phonemic awareness. These games can build vocabulary and phonemic awareness. Vocabulary Games - The Fun way to Learn Words Starting Early Two games to mention: The alphabet game. The first level starts as early as age 3 with just reciting the alphabet going back and forth between parent and child (this often is done while driving). Once this "level" of the word game gets too easy, its time to play the game with words and go back forth with: "Apple, Baker, Cat etc". You might play the game twice in succession and in the second round, you must use new words which makes it a tougher vocabulary game. At the next level, we restrict the word to just one type such as foods: "Apple, Banana, Cheese, etc". The next level of this word game might require two syllable