L'exposition, organisée au Little Haiti Cultural Center de Miami, présente un ensemble d'œuvres d'artistes contemporains des Antilles françaises, mettant en lumière leur volonté d'affirmer leur singularité artistique malgré les préjugés historiques. Cette initiative découle d'une volonté de revisiter les enjeux de l'identité et de la dignité, en confrontant les problématiques post-coloniales liées à l'esclavage. L'événement s'inscrit dans une série plus large, visant à accroître la visibilité des artistes de la région dans un contexte artistique international.

![45

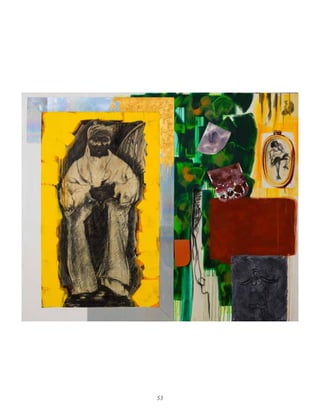

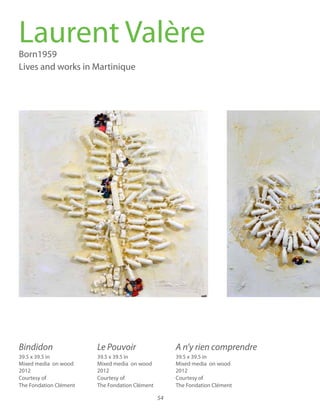

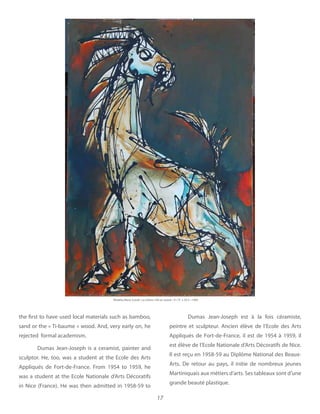

Christophe Mert (b. 1974) was born in Rivière-Pilote, Martinique. His paintings are renowned across

the Caribbean for their incorporation of diverse materials. Mert has exhibited in gallery shows Guérisseur

at the Atrium in Fort-de-France (2011) and Area gallery in Paris (2005), Résurgence de la Parole [SAN-

MO] at Salon Taïnos, Palais des Congrès de Madiana (2010), Carifesta IX in Trinidad (2006), and Miroir reflets

d’identité plurielle at Salle Lumina Sophie dite Surprise de Rivière Pilote (2006). Mert lives in Martinique.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/globalcaribbeaniv-final-130605103016-phpapp02/85/Catalogue-de-Global-caribbean-IV-53-320.jpg)