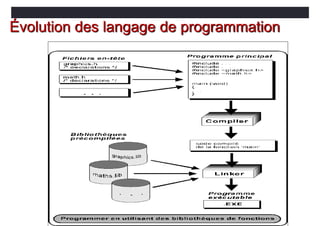

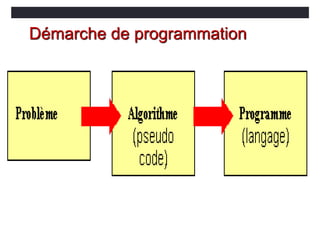

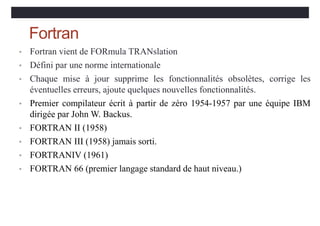

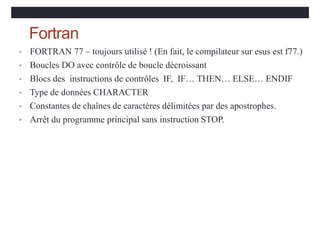

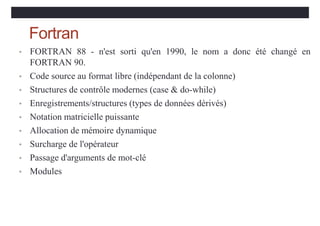

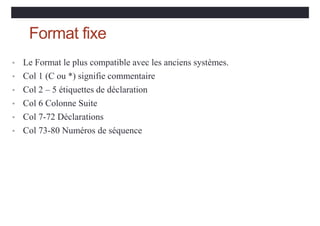

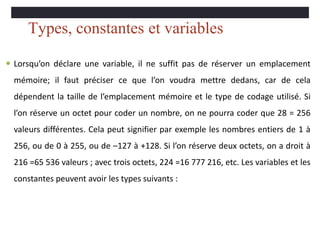

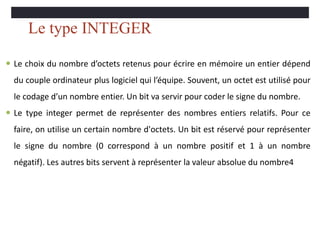

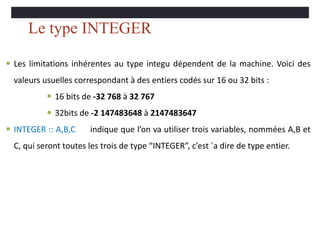

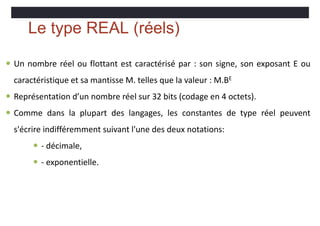

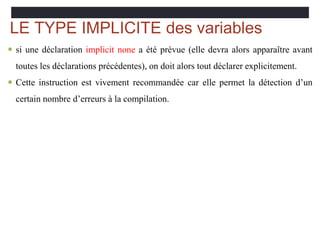

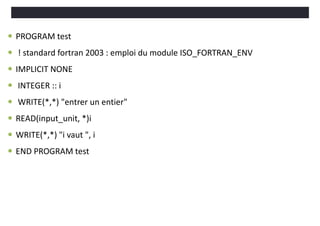

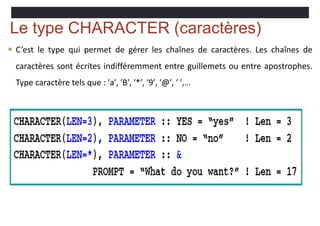

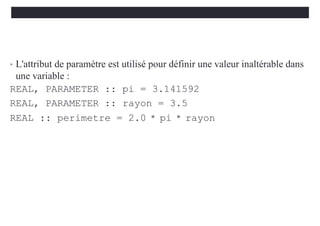

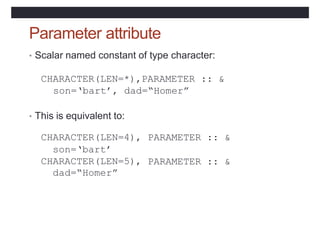

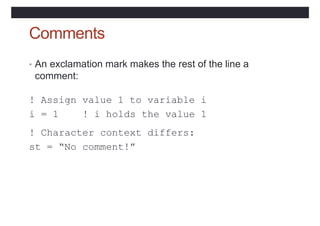

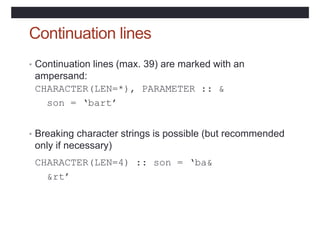

Le document présente une introduction au langage de programmation Fortran 95, décrivant son évolution et ses caractéristiques fondamentales. Il aborde les concepts de base de la programmation, les types de données, ainsi que la démarche de programmation, incluant la définition des algorithmes et leur traduction en code source. Enfin, il détaille les spécificités syntaxiques du langage et la gestion des variables, constantes et types.

![Variableetvaleur

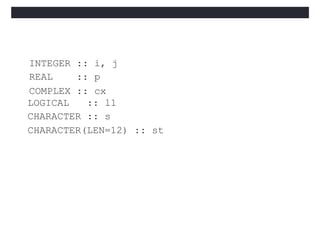

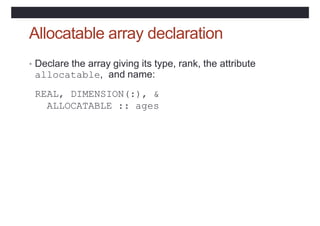

• La syntaxe formelle d'une déclaration d'une variable d'un type

donné est

•<type>[,attribute-list] :: &

<variable-list>[=value]

INTEGER :: k = 4

REAL, PARAMETER :: pi = 3.14159](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/coursfortran-221217222028-47986971/85/cours-fortran-pptx-35-320.jpg)

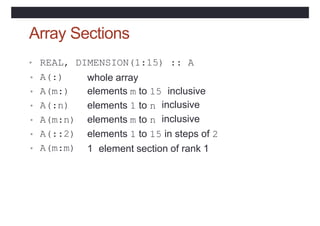

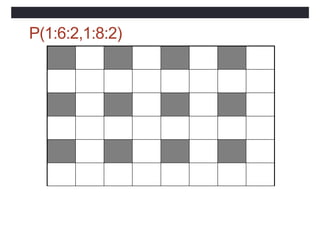

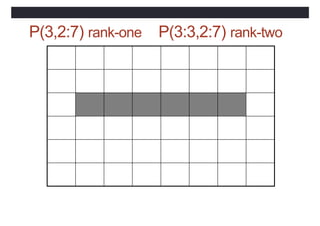

![Array Sections

• Specified by subscript-triplets for each dimension:

• [<bound1>]:[<bound2>]:[<stride>]

• <bound1>, <bound2> and <stride>

• must each be scalar integer expressions](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/coursfortran-221217222028-47986971/85/cours-fortran-pptx-113-320.jpg)

![Main program syntax

[PROGRAM [<main program name>] ]

<declaration of local objects>

<executable statements>

[ CONTAINS

<internal procedure definitions> ]

END [PROGRAM [<main program name>]]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/coursfortran-221217222028-47986971/85/cours-fortran-pptx-154-320.jpg)

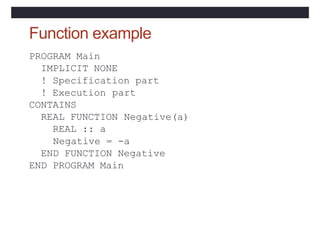

![Function syntax

[<prefix>] FUNCTION <proc-name> ([<dummy

args>])

<declaration of dummy args>

<declaration of local objects>

<executable statements, assigning result to

proc-name>

END [FUNCTION [<proc-name>] ]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/coursfortran-221217222028-47986971/85/cours-fortran-pptx-156-320.jpg)

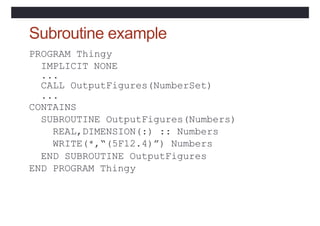

![Subroutine syntax

SUBROUTINE <proc-name>[(<dummy args>)]

<declaration of dummy args>

<declaration of local objects>

<executable statements>

END [ SUBROUTINE [<proc-name>]]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/coursfortran-221217222028-47986971/85/cours-fortran-pptx-160-320.jpg)

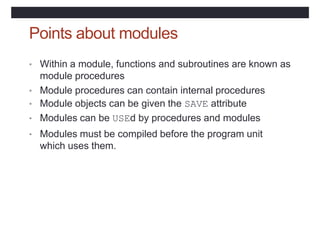

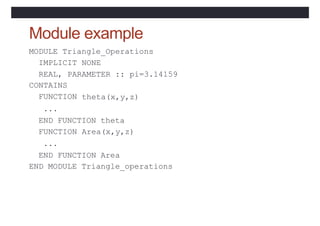

![Module syntax

MODULE module-name

[ <declarations and specification statements> ]

[ CONTAINS

<module-procedures> ]

END [ MODULE [ module-name ]]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/coursfortran-221217222028-47986971/85/cours-fortran-pptx-178-320.jpg)

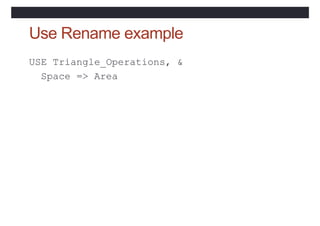

![USE rename syntax

USE <module-name> &

[,<new-name> => <use-name>]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/coursfortran-221217222028-47986971/85/cours-fortran-pptx-182-320.jpg)

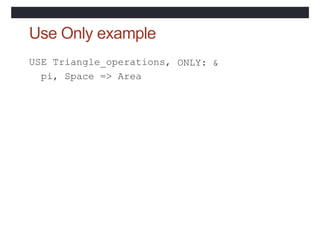

![USE ONLY syntax

USE <module-name> [, ONLY : <only-list>]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/coursfortran-221217222028-47986971/85/cours-fortran-pptx-184-320.jpg)