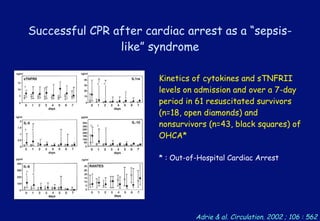

Le document traite des causes et de la prise en charge de l'arrêt cardio-respiratoire chez les adultes, mettant en avant l'importance d'une intervention rapide telles que la réanimation cardio-pulmonaire et la défibrillation. Il souligne également les conséquences de l'arrêt, les recommandations internationales sur la réanimation et la nécessité d'une réévaluation et d'un traitement approprié lors du retour de la circulation spontanée. Enfin, il aborde des avancées récentes telles que l'hypothermie thérapeutique pour améliorer les résultats neurologiques après un arrêt cardiaque.

![Cardiopulmonary resuscitation

without ventilation

Kern KB. Crit Care Med 2000 ; 28 [Suppl.] : N186 – N189

« Evidence continues to mount from many

sources including experimental work, clinical

observations, and basic life support (BLS)

training studies supporting chest compression-

only BLS cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR)

as a viable alternative for bystanderlayperson

CPR »](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/acr-140515155811-phpapp02/85/Acr-83-320.jpg)